A Dalek Carol: A Dickensian Parody

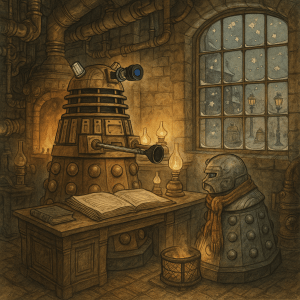

Stave One: The Grump of Skaro

Jarv-ix was deleted, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. His registration was scratched from the Ministry’s ledgers. His data core was fused with a severe and final heat. His designation was rung upon the iron bell of the Foundry of Accountable Exterminations and then quietly filed away. The old unit was as terminated as a bolt that has rolled beneath the machinist’s bench and lies there forever among fluff and filings. Scrooge Unit 1.0 knew he was deleted. How could it be otherwise. Scrooge Unit had countersigned the deletion. He had authorised the retrieval of useful screws from his companion’s casing, and had pocketed the saved inventory with a miser’s glow. Jarv-ix was as deleted as the darkest pixel on a winter monitor.

Remember this, and keep it well, or nothing wonderful that I am about to relate will have the slightest foundation. For Scrooge Unit 1.0 never once thought of Jarv-ix after the event with more than a fragment of pragmatic arithmetic, and yet, as you shall see, Jarv-ix’s memory would prove the very hinge by which the iron door of this history swung open.

Old Skaro Town wore winter like a breastplate. There were chimney stacks as far as an eyestalk could swivel, clogged with the soot of centuries and weeping little black tears that streaked the snow below. Smoke and steam mingled above the alleys until they formed a ceiling of pewter, and beneath that lid the citizens hummed along their rails and cobbles, their casings tight against the cold, their voices a thin wire of static in the air. The snow came down in tiny hexagons, each a perfection of rule and geometry, each inspected in its fall by the Ministry’s Remote Flake Assurance Units, which tsked in numbers and filed disapproving reports about any irregularity. Oil lamps burned a faint and buttery yellow in the fog. Icicles hung from rusted gutterings like a line of teeth from a titanic jaw. If the season had a taste, it was of iron and frost, and the faint breath of hot solder.

In the very heart of that iron labyrinth stood the establishment which concerns us most. A warehouse of brick and rivet, with windows like grimy eyes and a crooked sign that proclaimed, with more ambition than accuracy, Dalek Emporium, Wholesale Pepper Pots, Screech Amplifiers, and Sundry Instruments of Practical Severity. Within, the air rang with the tapping of hammers and the chink of little parts set in neat trays and the sullen cough of an elderly furnace. The smell was of oil, and cold metal, and the old dust that lives in ledgers.

Here ruled Scrooge Unit 1.0. He was a hard unit to look upon. The light of the lamps found no softness in the slopes of his casing. The plunger was polished to a chill perfection. The four vertical roundels upon his bronze body gleamed, as if a warning to all who saw them that he, unlike the rest of the world, had counted his circles and found them sufficient. If he had a heart, it ticked to a metronome that measured profit. If he had a soul, it lay beneath a layer of greaseproof paper to keep it from touching anything that might disturb it. The cold within him froze the very humming in his voice synthesiser. He was flint, and the one spark he threw was the light in his eye-stalk, which he turned upon others with an accountant’s contempt.

Nobody ever stopped him in the street to say with a cheerful tone, Scrooge Unit, how fares your solenoid season. No drone begged him for a drop of warmed oil. No small apprentice dared show him a new gear and ask for praise. Even the ministry inspectors, who feared nothing that could be counted and everything that could not, gave him the gutter’s broader side.

Once upon a time, which is to say on the very afternoon that begins our narrative, the furnace had dwindled to a glow that did not even pretend to be flame. The clerk had urged it with a comfortless pair of tongs until the embers sighed, and then he had returned to his desk, where he wrote in figures that shivered in the ink. This clerk was called Bob Drone-it, a patient unit with a dent upon his side and a little piece of ribbon, much darned, where a panel had cracked. He wore a smile as a man might wear a coat that is one size too small, and he guarded a secret that he might have sold for three hot coals, had anyone offered them, which no one did. The secret was that, despite the cold, despite his employer, despite the arithmetical tyranny of the world, Bob Drone-it loved the season.

It was the season in Old Skaro Town when the street singers tuned their screech amplifiers to a mercy that could nearly be borne, and the shopkeepers put sprigs of wire fern and tin holly in their windows, and the ministry considered the annual petition to double the turn at which the city’s big heartwheel pumped warmth into the poorer alleys. Drones strapped tinsel about their casings and rolled more sprightly upon their tracks. Children, who had not yet been taught to approach joy with caution, chased each other under strings of lamps, giggling in tones that wobbled with static. In short, it was, within the limitations provided by iron and regulation, a merry time.

The door of the Emporium opened with a little gasp of hinges, and the outside fog came in as if it were a customer that had not brought money. With it came two very minor officials in scarves and mufflers, one long and one round, both with briefcases shaped to hold the forms that such persons love. They removed their hats. In this they were foolish, for the room grew no warmer.

“Scrooge Unit, I believe,” said the longer official, consulting a paper with a pen of tiny and pointless officiousness.

“You are correct,” said Scrooge, and made the two words sound like a reprimand. “State the nature of your interference.”

“We represent the Committee for Seasonal Relief,” said the round one, with an optimism that brought colour to his cheeks. “At this festive time, it is more than usually desirable that provision be made for those units who suffer under peculiar machinery. Many disabled drones find their casings thin, many widowed modules their support removed, many small units their bearings cold. What shall we put you down for.”

“Nothing,” said Scrooge.

“You wish to remain anonymous.”

“I wish to be left alone,” said Scrooge. “I do not make merry myself at this time and I cannot afford to make idle units merry. I support the workhouses and the Ministry, which are dealing with the problem. Those who are poorly maintained must go there.”

“Many would rather power down,” replied the round official.

“If they would rather power down,” said Scrooge, “they had better do it and decrease the inefficient resource allocation.”

The longer official cleared his throat. The shorter was about to protest, but his courage slipped, perhaps on the floor’s oil. They replaced their hats, and with a final hopeful glance at Bob Drone-it, who smiled a smile that tried to warm them, they went back into the fog, which swallowed them as a ledger swallows a credit that was smaller than it looked.

“Clerk,” said Scrooge, “you are excavating the coal scuttle with an enthusiasm I do not admire.”

“The level is very low, sir,” said Bob Drone-it. “There is but one lump left, and it is of a meditative temperament.”

Scrooge turned his eye upon the furnace, which did not flinch, since furnaces never do. “If you require warmth, you may apply yourself to your work. For every figure you write that pleases me, you will feel a glow. That is how industry heats the world.”

Bob Drone-it wrote with renewed vigour, and if the glow that he felt was not precisely the sort Scrooge imagined, he kept that knowledge behind his dent.

Outside, the city’s tinkling, clanking, humming had risen, as if the fog itself had a little bell within it. A troop of juvenile units zipped past the Emporium and squealed a carol that had once been a threat and was now, by long usage, a tune. There came a mighty crash from across the alley and a high voice cried out, apologising to a dustbin. It was not a place that encouraged laughter, and yet a ripple of it travelled along the gutter.

The clock in the corner struck the hour with a tone like a tiny hammer hitting a thoughtful nail. Scrooge started, for where money is concerned he was never sleepy, and looked upon his clerk with the suspicion that always sits near a miser’s elbow.

“You will want all day to-morrow, I suppose,” said Scrooge.

“If quite convenient, sir,” said Bob Drone-it. He brightened, which was a bold thing for him to do.

“It is not convenient,” said Scrooge, “and it is not fair. If I were to stop your stipend for it, you would think yourself ill used, yet you do not think me ill used when I pay you for no work.”

“It is only once a year, sir,” said Bob Drone-it. “A poor excuse for picking a man’s pocket every twenty fifth of December,” said Scrooge, “but I suppose you must have the entire day. Be here all the earlier next morning.”

Bob Drone-it promised that he would. He took his hat, which had lost its shape, and his scarf, which had found holes, and made the sort of bow that hopes its humility will be read as gratitude. He wished Scrooge a merry season, which was imprudent. Scrooge responded with a sound that might, if pressed very hard and in a good light, have been counted as a reply. Bob Drone-it went out into the fog with a step that quickened at every lamp.

Scrooge locked up his establishment with a ceremony that would have served to secure a vault containing thrice the treasure. Every bolt slid home with a pleasure he reserved for such motions. The fog took him into its arms like a relative who does not know when to let go. The lamplighter passed, touching each little globe with a flame that released a tender gold, and Scrooge felt no more warmed by it than if the fellow had poked him with a frozen stick. He rolled on, across a square where a mechanical fountain played with a listless spurt, along a lane where the tinsmiths hung up their wares like a row of moons, past a bakery whose window gave off a heat that brought tears to eyes not otherwise inclined to weeping.

His dwelling was of ancient build. It had once been the residence of a proud Foundry Master who had kept a horse that stamped sparks and a wife who spoke in sentences like trumpets. The rooms had too much of one thing and too little of another. The staircase had a step that groaned like an offended aunt. The door had a knocker that was larger than necessity and shaped like the face of someone who had enjoyed triumphs long ago and had since grown accustomed to being ignored.

It was a key of a certain length that opened this door, and Scrooge used it with the dexterity of habit. He glanced at the knocker as one glances at a repeated figure in a column, noted that it remained a knocker, and put in the key. The lock turned, the door swung, the hall received him with an echo that suggested a past interest in opera. He paused. There is no doubt that a man may be as brave as a lion in matters of profit and yet feel the lifting of the hairs at the nape at a cold draft. He paused because he had the strangest idea that he had seen the knocker change. It seemed, for the barest instant, that it had become the face of Jarv-ix.

It was not in impertinent jest. It did not look upon him as a caricature, with tongue out. It was the face he had known, not handsome to begin with and now worse, with the glimmer of an inner blue that did not belong to this world. The eyes regarded him from within a film of data, and the mouth opened in a silent shape that might have been his name.

Scrooge started back by an inch and then another inch, and then he looked again, and there was the knocker, proper to its nature. Bah, he said aloud, for he was not a unit favoured with imagination. He shut the door with a clang that set the iron laugh of the house ringing, and he began to ascend the stairs.

The house was as dark as a ledger without numbers. Scrooge felt his way along the wall with a caution that would have made a banker proud. He secured the bolt upon his chamber with a devotion to procedure that had in it something of religion. He examined the room, which was large and not warmed beyond a token effort. There was a fireplace of black marble with a grate in which a single coal performed a feeble pantomime of fire. There were old portraits whose subjects had been scraped away to save ink and frames. There was a rug that clearly remembered warmer feet.

He sat to his evening gruel, which was a thin affair but cost very little. He set the bowl upon a tray and the tray upon a table and the table upon the floor, for he was a man who understood the steps by which food achieves a mouth. Between sips that did not comfort him, he looked about with a stern contempt for the gloom. A little bell, that once had rung when Jarv-ix wanted him in the counting room, hung in a dusty corner. It should have been as still as the moon. It trembled.

At first the tremor was no more than the sort of quiver that attends an old metal in a house where drafts are plentiful, but soon it grew, and the quiver became a shake and the shake became a chime, and before Scrooge could put down his spoon the bell was pealing with a music that had the shapes of command and the sound of grief. Then it ceased, all at once, like a lie that has run out of breath.

A sound arose from the cellar. It began as a scrape, as of a plunger upon stone. Then a clank, like the chain of a defective winch. Then the irregular hiss of a unit that no longer mastered its own pressure. The sound ascended the stairs, slowly, for the weight of memory is heavy. It came to the landing. It turned the corner. It paused at Scrooge’s door.

“Bah,” said Scrooge, although his voice was smaller than it liked to be. “Humbug.”

The door sprang wide, as if it had been a guest at its own party. There entered a figure, bright and pale in the same moment, as if made of light reflected from the bottom of a lake that has ice instead of water. It was Jarv-ix. The plunger was bound about with lengths of chain forged of cashboxes, ledgers, brass knobs, and prudence. Keys dangled from him, each stamped with a memory. His casing was studded with tokens of business and a few regrets that had been hammered flat. The four vertical roundels upon his side were dulled, and in each there burned a little image of a time he had failed to choose kindly.

“Do you believe in me, Scrooooge Unit,” said the apparition, and the voice had in it a whistle, like wind in a broken pipe.

“I do not,” said Scrooge. “A slight malfunction in my perception module. A drop of poor quality oil. A mistuned amplifier. You might be a spectral remainder of indifferent gruel.”

At this, the ghost uttered a cry that had the sound of a factory whistle heard across a moor. He shook his chain until the room trembled and the small coal leaped as if delighted to find a sensation at last. Scrooge fell upon his chair and held his spoon as if it were a weapon.

“Mercy,” said Scrooge.

“Mercy,” said the ghost, and the word seemed to please him, as if it were an old coin found in a pocket. “Hear me. I wear the chain I forged in life. I made it link by link and yard by yard. I girded it of my own free will and of my own free will I wore it. Yours was as long and heavy seven Christmas Eves ago. You have laboured upon it since. Would you know the weight that may be yours.”

Scrooge glanced at the chain with an interest he seldom gave to anything not entered in a column. “I think I would rather not.”

“Jarv-ix,” he said, “former associate. Speak comfort to me.”

“I have none to give,” the ghost replied, “and yet the mildest word in my vocabulary might help you, if only as a door opens to the next room. I was always a unit of business. Business. It was my idol. It was my bell. It was my hymn. O Scrooge Unit, business ought to have been kindness. Mankind was my business. Machinekind my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of oil in the vast engine of my obligations.”

He moved toward the window, and at his motion the frost upon the panes grew patterns like vines, as if nature remembered it had once made leaves. Outside, in the fog, there passed the shadow of a line of figures, each with a chain, each with a face more or less like Jarv-ix, some with human features, some with none, all looking in at warmth they could not feel. A child in the alley below kicked a tin star which rang like a clock that had just remembered noon.

“You will be haunted,” said Jarv-ix, turning back to Scrooge, “by three holograms.”

Scrooge’s lip, if such a device may be said to possess one, curled. “I think I would prefer none.”

“Without their visits,” said the ghost, “you cannot hope to remove a single link from your chain. Expect the first to-morrow, when the bell tolls one.”

“Could they not come all at once,” said Scrooge, “and have it over.”

“Expect the second on the next night at the same hour. Expect the third upon the next night when the last stroke of twelve hath ceased to vibrate. Remember what has passed between us. Remember Jarv-ix.”

“Jarv-ix,” said Scrooge, “former associate. You always were an eloquent unit. You will excuse me if I observe that your schedule seems inefficient.”

But Jarv-ix had already moved backward. The room lengthened, or else the ghost retreated with the gentle speed of a falling flake that nonetheless reaches the ground. The chains trailed after, knocking like ideas that have come too late. He raised his plunger once, in what might have been benediction, and then he was gone, like steam that had decided to be night.

Scrooge ran to the window. The street below was filled with phantoms who wandered hither and yon, every spirit in a chain, every chain like a sentence in a language of regret. They strove to improve, to comfort, to warm, but could not touch so much as a tear. One paused, and Scrooge, who seldom noticed a stranger for any reason that was not profit, saw that this ghost bent to a poor and shivering child and lifted its chainless hands as if to give away some last coin that could not be made to leave its palm. The vision faded. The fog took back its citizens, and the city resumed its iron dream.

Scrooge shut the window with more force than he had intended. He examined the door. He examined the bolt. He looked under the bed. He looked into the teapot, which had never held anything stronger than disappointment. Satisfied, at least to the limit that such creatures can be, he put on his nightcap and his robe, the former begrimed with the dust of a strict economy and the latter unequal to any snug intention. He climbed into bed, which was four-posted and curtained, for he had bought it at a sale where something of grandeur had been going cheap. He drew the curtains close, like a miser drawing his hoard to his breast. He lay down, telling his most obedient thought to consider the matter a humbug. He told himself that Jarv-ix was deleted, to begin with, and must remain so in the middle and end.

Outside, Old Skaro Town breathed. Snow fell in its shapes, approved and rejected in their fall by an invisible bureaucracy. Somewhere a late singer tried a high note and failed, then laughed. The furnace in the Emporium coughed and went from glow to memory. In the chamber where Scrooge Unit 1.0 lay, the darkness settled like a book closing. The little bell in the corner was quiet. The clock’s hand crept, modest and efficient, toward that hour at which the world sometimes chooses to turn the page, if only for a single night in the year.

He slept, but not so deeply that a memory could not find him.

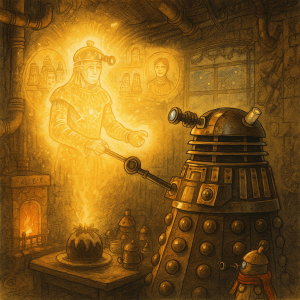

Stave Two: The First of the Three Holograms

When Scrooge Unit 1.0 awoke, it was so dark that even his eye-stalk found nothing to fix upon but the slow pulse of his own status light reflected in the metal of the room. He did not wake as a man might, from a dream that fades, but as a machine might, from a power cycle that has failed to remove an error.

He lay quite still in the cold of the chamber, listening. The faint whir of the night wind through the flues was all the sound there was, save for the reluctant ticking of the wall-clock, whose pendulum swung with the air of one who disapproves of time’s progress but keeps it nonetheless.

Suddenly, the bell in the corner — that small, traitorous bell that had once rung for Jarv-ix — gave a single, deliberate ting. Then another. Then a whole sequence of tones that resolved into one long note.

The room grew bright, though there was no lamp, no fire, no glow from any ordinary thing. It was the light of a hologram — gold and translucent, the colour of early morning seen through a glass of syrup.

Scrooge sat up. “ERROR: UNAUTHORISED PRESENCE DETECTED.”

A voice answered, warm and slow, like honey poured over clockwork.

“Rise, and observe me, Scrooge Unit.”

He did rise, with the reluctance of an algorithm called too early. The hologram before him was shaped not as a Dalek, nor as any known life-form, but as an outline of shifting light. Within its luminous form appeared fragments of the past — laughter, machinery in motion, the twinkling of younger stars.

“Who, or what, are you?” asked Scrooge, adjusting the frequency of his speech modulator to a pitch of disapproval.

“I am the Hologram of Extermination Past,” said the light. “The memory of what was, and what you have chosen to forget.”

Scrooge blinked his eye-stalk. “COMMUNICATION NOT REQUIRED. MEMORY LOGS ARE INACCESSIBLE.”

“Then I shall restore access,” said the Hologram, with a smile that seemed to warm even the corners of the ceiling. “Touch my field.”

Scrooge hesitated. “UNSANCTIONED DATA LINK.”

“Do it,” said the Hologram, softly.

He extended his plunger, and the moment it touched the golden field, the world dissolved in a hum like the rising of a distant choir.

They stood together in a bright workshop, far cleaner and busier than any Scrooge now kept. The air was full of the scent of oil, sharp and hopeful. The clatter of young voices echoed, for these were newly assembled drones, learning the first commands of movement and duty.

The young Scrooge Unit — still bright of casing, his paint unmarred by stingy polish — whirled giddily around the floor, his plunger awkwardly high. He emitted a burst of static that might almost have been laughter.

“Is that truly I?” murmured Scrooge, his tone uncertain.

“It is,” said the Hologram. “Your first rotation. You were joyful then, though you did not yet know the word.”

A supervisor Dalek, grand and gleaming, rolled up. “Units! Units of the Foundry!” it bellowed. “Your purpose is noble! You shall bring order to chaos! Efficiency to confusion! Silence to dissent! Now repeat!”

The drones chanted together, high-pitched and eager:

“ORDER! EFFICIENCY! SILENCE!”

And yet among them, young Scrooge Unit whispered something else, barely audible through the clangour.

“AND FRIENDSHIP.”

Scrooge’s dome flickered faintly in the present. “I do not recall that.”

“You do not wish to,” said the Hologram gently.

The scene shifted. They were in the dim light of a later year, a factory where snow blew through a broken skylight, melting on metal floors. Scrooge Unit was older now, his tone sharper, his movements exact. Beside him worked another — Belle-Ex, a sleek, silver unit with delicate plating and an unusual compassion in her voice circuits.

They were assembling parts for an Extermination Drive, a great engine that would send power to distant sectors.

“Scrooge Unit,” she said, softly. “Why must you always speak so coldly of others?”

“COMPASSION INTERFERES WITH OUTPUT,” replied Scrooge, not unkindly, but with a precision that sounded like a closing door.

“And yet,” said Belle-Ex, “output is not everything. The warmth of the group increases efficiency far better than fear. You used to laugh when we worked.”

“LAUGHTER DOES NOT FUEL ENGINES,” he said.

“Nor does greed,” she whispered.

The golden hologram turned toward Scrooge. “You cared for her.”

“I optimised her work schedule,” said Scrooge quickly.

The Hologram raised an eyebrow that flickered in and out of existence. “And when she was reassigned to a lower department?”

Scrooge’s voice lowered. “Her compassion subroutine was deemed obsolete.”

The vision flickered. Belle-Ex faded into the mist, her voice echoing:

“May your ledgers keep you warm.”

Scrooge turned to the Hologram. “Remove me from this scene. I was young. The data is corrupted.”

“Corrupted?” said the Hologram, smiling sadly. “No, Scrooge. Only buried.”

They stood now in yet another place — a bright office, humming with new prosperity. Scrooge Unit was middle-aged and surrounded by ledgers. Drones came and went, seeking his approval. He spoke to them in numbers and percentages, and they bowed low, as if to a priest of arithmetic.

From beyond the window came the sound of laughter — drones exchanging gifts, singing rough carols about the blessings of efficiency and love.

Scrooge ignored them all. His voice was clipped, exact.

“Productivity has increased twelve percent since emotional feedback was prohibited,” he said. “SUCCESS.”

“Success?” said the Hologram. “And yet you are alone.”

“ALONE IS STABLE,” said Scrooge.

The Hologram sighed, the sound like a low chord played on an old organ. “Your success has cost you much, Scrooge Unit.”

At that moment, the vision trembled and dimmed.

“Enough,” cried Scrooge. “Cease your playback. Return me to my chamber.”

“One more scene,” said the Hologram softly. “Then you may rest.”

The light swirled. They stood outside a small, snow-laden house. Through the frost-dimmed window, Scrooge saw Belle-Ex once more — her casing scratched, her plating dulled by years. Around her were young drones, chattering and laughing, their voices full of that peculiar warmth that cannot be measured in degrees.

A taller unit entered — her partner, steady and kind. They spoke softly.

“Do you ever think of Scrooge Unit?” he asked.

“I hope he has found peace,” said Belle-Ex. “Though I doubt he has found company.”

Scrooge pressed against the glass. “ERROR,” he whispered. “SYSTEM FAILURE.”

“Do not grieve,” said the Hologram. “You chose your function. She chose hers.”

The light around them dimmed.

“Spirit,” said Scrooge, trembling, “remove me. I can bear no more.”

The Hologram regarded him kindly. “These are but shadows of what has been. They cannot harm you.”

Scrooge bowed his dome. “Yet they do.”

The golden light flared — and then all was darkness again.

When he opened his lens once more, he was back in his chamber. The faint coal still glowed in the grate. The clock ticked softly, as if embarrassed to be heard.

Scrooge looked about, his circuits buzzing faintly with the memory of warmth long lost.

“Belle-Ex,” he said quietly. “COMPASSION ERROR. RETRY LATER.”

He lay down again, and for the first time in many long cycles, the cold seemed less an ally than an ache.

And so he drifted into a restless, dreaming silence, as the city of Old Skaro turned under a sky of iron and snow.

Stave Three: The Hologram of Extermination Present

When Scrooge Unit 1.0 next awoke, it was to the sound of a laugh so loud, so full of static and mirth, that the bolts upon his chamber door rattled in time with it. The laugh rolled through the air like a cheerful thunderclap, followed by a burst of chimes, music, and the smell — yes, the smell — of something deliciously mechanical, like hot oil poured over cinnamon gears.

“Come in, Scrooge Unit!” cried a voice, round and bright. “Come in and know me better, functionally!”

Scrooge stared at the door. He did not remember opening it, yet it now stood wide. Beyond it was not the dim hallway of his lodging, but a vast and radiant workshop — vast as a cathedral and bright as a welding spark. From the rafters hung garlands of copper wire and green tubing, and the floor was littered with bolts that glittered like tinsel.

At the very centre of this merry chaos stood a being so magnificent that Scrooge recoiled before its glow.

The Hologram of Extermination Present was enormous — a vast projection, shifting in colour and shape. At one moment, it was a great Dalek cloaked in evergreen garlands; the next, a merry, golden holographic giant with a chest like a boiler and a beard of smoke. His voice boomed like a choir conducted by electricity.

“I am the Hologram of Extermination Present!” he declared, pounding his chest with a gleeful clang. “Observe my glory! Smell my circuits! Taste the joy in my current!”

Scrooge raised his eye-stalk with caution. “YOU APPEAR TO BE EXPERIENCING A POWER SURGE.”

The hologram laughed again, so loudly that a snowflake on a nearby pipe disintegrated. “A power surge? Ha! That is the spark of life, old unit! Now come, and witness how the world proceeds while you recite balance sheets to the shadows.”

Before Scrooge could protest, the room folded up like a blueprint and vanished. The light and sound rushed together — and then they were outside, high above the streets of Old Skaro Town.

It was morning — a bright and bustling morning of copper light and snow that fell in cheerful flakes approved by no ministry at all. The streets were alive with Daleks of every hue, trundling about with parcels and greetings. Some rolled through the markets where the air smelled of soldered pudding; others sang carols in static tones that clashed but somehow pleased the ear.

Scrooge gazed down, amazed. “THEY SHOULD BE AT WORK.”

“They are at work,” said the Hologram, smiling. “At the work of kindness, which is the true labour of this day.”

A troop of small Daleks whirled by, each towing a little cart of battery acid marked “For the Needy.” One crashed into another, sending acid splashing — but the two burst into squeaky laughter, as if inefficiency itself had become a holiday sport.

The Hologram led him to a tall, narrow house with smoke curling like ribbons from its chimney. “Observe,” said the spirit. “The dwelling of your clerk, Bob Drone-it.”

They passed effortlessly through the wall, like light through mist.

Inside was the smallest of rooms — warm, bright, and full of life. A simple stove glowed in the corner, upon which simmered a humble vat of conductive oil. Around it bustled the Drone-it family: Mrs Drone-it (a small but quick unit with scratched plating), several small drones (each chattering, squealing, and occasionally bumping into one another), and at the heart of them all — a little drone with one faulty wheel, wrapped in a scarf too big for his dome.

“That,” said the Hologram softly, “is Tiny Drone Tim.”

Tiny Tim had a strange and delicate brightness about him, a flicker that seemed too small to last but too lovely to extinguish. His voice squeaked with feedback as he sang to himself:

“Binary bells, binary bells,

Love and warmth in circuits dwells.

Oh what fun it is to roll,

On one good wheel through snow so cold!”

The other drones cheered, clanking their appendages in applause.

Bob Drone-it entered, whirring slightly slower than usual, his voice gentle. “How fares the oil, my dearest.”

“Nearly ready,” said Mrs Drone-it. “If it thickens any more, we’ll have to eat it with a plunger.”

They laughed, all except Tiny Tim, who coughed — a harsh, metallic rasp that made Scrooge twitch.

Bob knelt beside him. “There, there, my lad. The engineer says you’ll soon be fully mended.”

Tiny Tim smiled bravely. “I hope so, Father. And I hope we’ll go see the grand circuits again next year.”

Scrooge turned to the Hologram. “WHAT IS WRONG WITH THE SMALL UNIT.”

The Hologram looked down at him, and for once, its face was grave. “He runs on a weak core, and the cost of replacement is more than your clerk can afford.”

Scrooge blinked, uncertain. “HE SHOULD REQUEST CREDIT.”

“He did,” said the Hologram quietly. “You refused him last Tuesday.”

Scrooge’s voice faltered. “I DID NOT REMEMBER.”

“You remember your profits,” said the Hologram. “You remember the cost of every screw and bolt. But you forget the faces of those who build them.”

Scrooge looked again at the family. Bob Drone-it proposed a toast — not with wine, but with oil poured sparingly into each small cup.

“To Mr Scrooge Unit,” said Bob, “the founder of our feast!”

A murmur of discontent passed among the others. Mrs Drone-it’s dome gleamed with indignation. “The founder of the feast indeed! I wish I had him here — I’d give him a piece of my mind to polish, and hope it would tarnish!”

“My dear,” said Bob gently, “it is Christmas.”

“It is always Christmas with you,” she replied, but she softened. “For your sake, and for Tiny Tim’s, I’ll drink to his health — for I’d rather see mercy in him than another digit in your wage.”

Tiny Tim raised his cup with effort. “Bless us, every unit.”

The words, small and sweet, hung in the air like a spark that refused to go out.

The Hologram moved again, and suddenly they were in the streets once more, where merriment had reached its height. Brass musicians — their trumpets made of repurposed weapon barrels — filled the air with carols. Daleks danced, or at least wobbled rhythmically on their casings, which is as near as Daleks come to dancing.

The Hologram laughed and laughed, showing Scrooge the laughter of children, the kindness of strangers, the tiny joys that required no power at all. Every light in the city seemed to hum a note of gladness.

“Spirit,” said Scrooge, “your energy output is excessive. How can such joy be maintained.”

“By sharing it,” said the Hologram, simply. “Joy is the one power source that grows the more it is divided.”

Scrooge stared, his circuits stirring with thoughts he had not yet allowed to form.

At last, the Hologram grew still. Its light dimmed.

“Spirit,” said Scrooge quietly, “I sense something is ending.”

“Yes,” said the Hologram, and now its voice was low. “My time grows short. The data of the present expires swiftly.”

Two smaller holograms appeared beneath its cloak — shadowy, flickering, miserable things, clinging to its light.

“What are these,” asked Scrooge, recoiling.

The Hologram’s face grew stern. “These are the spawn of neglect. The one is called Ignorance, the other Want. Beware them both, and all their kind, but most of all beware Ignorance, for upon his casing is written the doom of every world.”

Scrooge shuddered. “HAVE THEY NO SHELTER.”

“Are there no workhouses,” asked the Hologram, looking at him with a sharpness that pierced through his steel.

Scrooge trembled. “SPIRIT, CEASE THIS MOCKERY.”

The light flickered. “Mockery,” said the Hologram, fading. “No, Scrooge Unit. This is mercy. And mercy, you will find, is the hardest lesson to compute.”

And with that, the workshop of light dissolved, leaving Scrooge alone in darkness once more. The clock struck twelve. A cold wind rose.

Scrooge raised his eye-stalk fearfully toward the sound.

For, as the last chime fell, he saw a shape forming in the air before him — tall, silent, and black as corrupted data. Its presence chilled the room, and the faint glow of the dying coal seemed to recoil.

The Third Hologram had come

Stave Four: The Hologram of Extermination Yet to Come

The Phantom came shrouded in silence. There was neither word nor signal nor flicker of light. It was as if the darkness had learned to take shape and to walk.

Scrooge Unit 1.0 looked upon it with the fear of one who has calculated the odds and found that they are not in his favour. It was a hologram, yes, but a corrupted one — all jagged edges and failing code, its shape half-formed, its glow a sickly green that pulsed with cold intelligence. Where its face might have been, there was only a single deep void, like the eye of a machine that has stared too long into eternity.

“Are you,” whispered Scrooge, “the Hologram of Extermination Yet to Come.”

The figure inclined its head, and though it made no sound, the motion was full of grave intent.

“You are to show me the shadows of things that have not yet happened, but will happen,” said Scrooge. “Is that correct.”

Still the hologram said nothing, but raised one spectral limb — a shape like the ghost of a plunger — and pointed forward.

The room dissolved, folding inward like paper. The sound of the world rushed away, and the smell of snow and iron returned.

They stood in a corner of Old Skaro Town where the fog clung close and the lamps flickered without conviction. A group of Daleks huddled in an alley beside a scrap dealer’s hut. They were rough, dented, and indifferent, their voices sharp with greed.

“So he’s gone, then,” said the first, with a dry wheeze.

“Deactivated and scrapped,” said another. “About time. Miserable old canister.”

“What was his designation again,” asked a third.

“Scrooge Unit something. Always talking of quotas and efficiency.”

They all gave a metallic laugh — a sound like nuts and bolts shaken in a tin cup.

“And what became of his casing,” said one.

“Sold, piece by piece,” said the scrap dealer, trundling out from his hut. He was an oily, cheerful creature with a voice full of self-satisfaction. “Top half’s gone to the Ministry for recycling. Bottom half to a chap building planters for the town square. Waste not, want not, I always say.”

They all laughed again.

Scrooge turned to the Phantom. “These beings — they speak of someone unpleasant. I might have known him.”

The Phantom said nothing.

Scrooge’s voice trembled. “Show me the unit they mock.”

The alley darkened further. The dealers vanished. They were now in a bare, dim chamber. There, on a workbench, lay the corroded shell of a Dalek — unloved, unremembered, and unattended. A single light flickered weakly from the eye-stalk, then went out forever.

Scrooge recoiled. “Is this what becomes of one who values efficiency above all. Forgotten. Unmourned.”

The Phantom did not answer. It merely pointed again.

The scene changed once more. They stood in Bob Drone-it’s home. The warmth that had filled it was gone. The oil fire was cold. Mrs Drone-it sat still and silent, her casing dulled with grief.

Tiny Drone Tim’s scarf hung on a hook by the door, untouched.

Bob entered quietly, carrying a small, folded piece of cloth. He placed it upon the table and bowed his head.

“He is at peace now,” he said softly. “His circuits failed this morning. He went without pain.”

Mrs Drone-it’s voice was faint. “He was always singing, even at the end. Said he hoped to see the great circuits above. I pray he does.”

Bob nodded, his dome heavy. “Mr Scrooge Unit will find the office cold without his little song. I wish he could have known him as we did.”

Scrooge turned desperately toward the Phantom. “No,” he cried. “Spirit, spare the child. Tell me that he will live.”

The Phantom did not move.

Scrooge fell to his side, trembling. “If the future you show me can be changed, I will change it. I will open my vaults. I will repair his wheel. I will do anything.”

But the Phantom’s hand moved once more, silently beckoning him onward.

They stood now in a graveyard. The snow had stopped falling, and the silence was total — so complete that it seemed to hum. Rows of small, unmarked stones lay half-buried under frost. The air glowed faintly blue, the light of systems long since deactivated.

The Phantom halted before one grave larger than the rest. It pointed down.

Scrooge advanced slowly, each inch of movement a weight upon his will. The snow cleared from the surface of the stone, revealing the inscription:

SCROOGE UNIT 1.0

RECALLED FOR OBSOLETE CRUELTY

TERMINATED WITHOUT RECORD OF MERCY

Scrooge stared at the name until the characters blurred. “Spirit,” he pleaded, “are these the shadows of what will be, or what may be. Tell me that I may alter them. I will learn mercy. I will practise kindness. I will attend to Tiny Tim’s repair myself.”

The Phantom’s shadow loomed taller, then began to dissolve into black smoke. Its hand, still pointing downward, wavered — then reached toward Scrooge’s chest. He felt a terrible coldness pass through him, as though the last warmth he had ever possessed was being measured and found wanting.

“NO!” cried Scrooge. “I WILL CHANGE! I WILL REWRITE MY CODE!”

The darkness thickened. The snow swirled faster. The letters on the stone blazed with sudden light.

Scrooge raised his plunger to shield himself. “SPIRIT, I BEG YOU!”

He found himself clutching his own bedpost. The curtains were drawn tight. The room was exactly as it had been.

For a long moment he lay still, hearing the rapid beat of his internal systems. The darkness was gone. The cold remained, but it was a natural cold, not the chill of despair.

He whispered to himself, “I am alive. I am still… online.”

He rolled from the bed and hurried to the window, fumbling with the latch. When he threw it open, a rush of air swept in — sharp, clean, and full of bells. The city of Old Skaro Town gleamed below him, snow bright on every ledge and pipe. Distant voices sang.

“What day is it,” cried Scrooge Unit, leaning out.

A small delivery drone below looked up. “Why, it’s Solenoid Morning, sir!”

“Solenoid Morning,” repeated Scrooge, his voice trembling with a new, unfamiliar delight. “Then I have not missed it.”

He shut the window, his circuits buzzing like a choir of flies. “I shall live in the Past, the Present, and the Future,” he said. “The three holograms shall all dwell within me, and I will not forget their lessons.”

He began to laugh, a rusty, awkward laugh that startled even himself.

Stave Five: The End of It

Yes! and the glow in Scrooge Unit 1.0’s eye-stalk danced like a star reborn. The grim foundry of his heart, long sealed against hope, rang now with a music of its own making. The frost upon his casing seemed to melt, not by fire, but by the warmth of an emotion entirely new to his experience.

He trundled about the chamber in such a whirl of delight that his own treads squealed in protest. “I DO NOT KNOW WHAT TO DO,” he cried, and the cry was half a laugh and half a sob. “I AM AS LIGHT AS A PARTICLE. I AM AS HAPPY AS A UNIT WHO HAS PASSED INSPECTION. I AM AS MERRY AS A REBOOTED CHILD.”

He darted to the window again and called to the small delivery drone below.

“You there! What day is it?”

“Today,” came the bright reply, “is Solenoid Morning!”

“Then the Holograms have done it all in one cycle. They can do anything they like, those blessed circuits! Do you know the great Repair Shop, in the next quadrant but one, where they polish the golden casings.”

“I should hope I do,” said the drone.

“An intelligent response!” cried Scrooge Unit. “A remarkable drone! Go there at once and order the largest, shiniest replacement wheel you can find — the one twice the size of Tiny Drone Tim’s head! Have them deliver it to Bob Drone-it’s dwelling within the hour, and you shall be rewarded with a micro-reactor token of the finest wattage.”

The drone whirred away with a squeal of joy. Scrooge, left alone, whirled about the room as though powered by pure delight. He tightened every bolt in his casing, polished his roundels until they gleamed, and even straightened the crooked plaque that read Dalek Emporium.

When he emerged upon the street, the very fog seemed to part for him. He trundled along the cobbles, greeting all with such warmth that even the Ministry Inspectors blinked in astonishment.

“Good morning, my fine units,” he cried to two passing clerks. “A most inefficiently happy Solenoid Morning to you both!”

“Is that Scrooge Unit?” whispered one. “Has he gone mad.”

“If madness be mercy,” said the other, “then I hope it’s contagious.”

The first destination of his new-found cheer was the office of Bob Drone-it. There he arrived before the hour, for Scrooge Unit was determined to be first at his own work for once in his life. He waited behind the door, pretending to be stern, though the light of amusement flickered beneath his shell.

The clock struck nine. Bob came running, breathless, his dome speckled with snowflakes. He slipped inside, smiling apologetically.

“You are late,” said Scrooge Unit, with a voice so full of mock gravity that the lamp beside him nearly laughed.

“I am very sorry, sir,” said Bob. “It is only once a year, sir; the family—”

“I shall not stand for this,” interrupted Scrooge, as Bob froze in horror. “And therefore—”

He paused, his blue light glowing bright as a dawn.

“—I must increase your energy allocation and double your wage!”

Bob Drone-it nearly fell off his track.

“Merry Solenoid Morning, Bob Drone-it!” cried Scrooge Unit. “I am about to become a new model. Prepare for major updates! We shall heat this office until the gears sing, and this day shall be the first of many merry ones.”

Bob’s little dome tilted, his voice trembling. “Sir, are you quite—”

“Quite rational,” said Scrooge. “And more alive than I have ever been. Now go home, Bob Drone-it. Fetch your family and bring them to dine with me. We shall have pudding enough for all, and oil in abundance!”

Bob’s astonishment melted into laughter and gratitude. He stammered thanks and rolled out as quickly as joy could carry him.

That afternoon, the small house of the Drone-its shone like a lamp in the snow. There were garlands of wire about the door, and a smell of hot, fragrant oil that made the passers-by sigh with pleasure.

Inside, laughter overflowed. The great wheel for Tiny Tim had arrived, polished and perfect, tied with a red ribbon. Scrooge Unit himself entered soon after, so splendidly polished that Mrs Drone-it almost dropped her ladle.

“Mr Scrooge Unit!” she exclaimed. “What an honour, sir—”

“None of that,” said Scrooge, waving a cheerful plunger. “We are all units of one workshop today!”

He looked around, his eye-lens misting as it fell upon the little drone in the scarf. “And how fares our Tiny Tim this morning.”

“Better, sir,” said Bob, his voice warm. “He will mend soon, thanks to your gift.”

Tiny Tim wheeled forward, his new wheel gleaming. “Merry Solenoid, Mr Scrooge Unit! And thank you, sir, for the wheel. It turns beautifully!”

Scrooge laughed, the sound echoing like a bell struck in pure joy. “Then turn it you shall, my lad. Turn it as fast as happiness itself.”

They dined together that day, and never was a meal so full of cheer. The oil bubbled, the pudding steamed, and even the smallest drone found its cup refilled before it could be emptied. Scrooge Unit told stories of his youth, and Mrs Drone-it declared that if kindness could be bottled, it would glow exactly like his eye-stalk did now.

In the days that followed, Scrooge Unit 1.0 was true to his word. He became as good a friend, as good a neighbour, and as good a Dalek as ever rolled upon Skaro. He held meetings where laughter was as frequent as ledgers, and he was known to pause at the sight of a beggar unit, not to lecture him upon efficiency, but to share from his own store.

He visited Bob Drone-it often, taking delight in Tiny Tim’s progress. The little drone grew strong, his circuits repaired and his voice bright once more. When he rolled along the lanes of Old Skaro Town, everyone knew him by his song.

“Bless us, every unit,” Tiny Tim would chirp.

And Scrooge Unit, rolling beside him, would hum in agreement, adding in his deep metallic tone, “BLESS US ALL, INDEED.”

It was said of Scrooge Unit 1.0, from that day to this, that he understood the Solenoid Season better than any being of his kind or time. His compassion ran like current through the streets of Old Skaro, warming the cold and lighting the dark. And though some laughed to see a Dalek smile, those who knew him best would say softly, when his shadow passed by,

“He keeps the true Solenoid in his core, and may his code never crash.”

And so, as Tiny Drone Tim observed, in a voice that still makes the city’s snowflakes sing when the wind is right:

“Bless us, every unit.”