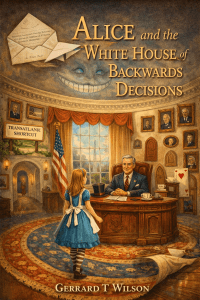

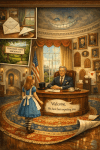

An original tale inspired by Lewis Carroll’s

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

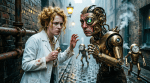

The fog over London wasn’t natural anymore. It carried the scent of oil and ozone, of brass and burning flesh. It clung to the cobblestones like a shroud, and in that shroud, the clicking began.

Tick. Tock. Tick. Tock.

Not the gentle rhythm of a grandfather clock, but the staccato march of a thousand tiny gears, grinding against bone.

Dr. Eleanor Whitmore pressed herself against the brick wall of the alley, her medical bag clutched to her chest like a shield. Her white coat was stained with soot and things darker than soot. Her stethoscope hung around her neck, useless now. What doctor could treat this?

She had seen Patient Zero three days ago. A dockworker, brought in with what she thought was tetanus. His jaw locked, his muscles rigid. But when she listened to his chest, she didn’t hear a heartbeat.

She heard ticking.

And then his skin had split open, not with blood, but with brass. Gears where his heart should be. Pistons pumping where his lungs had been. He had sat up on the table, his eyes replaced with glass lenses that whirred and focused, and he had spoken in a voice like grinding metal.

PERFECTION REQUIRES SACRIFICE.

Then the others had come. Not sick. Not dying. Transforming.

Eleanor checked her pocket watch. 11:47 PM. Thirteen minutes until midnight. Thirteen minutes until the great clock tower of Westminster would chime, and with it, the signal would spread. She had decoded the pattern in the transmissions. The plague wasn’t just mechanical, it was networked. Each clockwork victim was a node, broadcasting the conversion signal on a frequency only the dying could hear.

Click-clack. Click-clack.

The sound was closer now. She peeked around the corner of the alley.

They walked in perfect unison, these things that had once been people. Their limbs moved with jerky precision, joints replaced with ball-and-socket brass fittings. Some still wore tattered remnants of their clothes, a businessman’s suit, a maid’s dress, a child’s frock. But beneath the fabric, the truth was visible. Exposed clockwork. Glowing filaments where nerves should be. Eyes that reflected light like polished mirrors.

One of them stopped. Its head rotated 180 degrees with a sickening whirrrr. Glass eyes fixed on the alley.

DETECT ORGANIC LIFE FORM, it announced, its voice a chorus of overlapping mechanical tones.

CONTAMINANT IDENTIFIED, another responded.

PURGE INITIATED.

Eleanor ran.

She burst onto the main street, her boots slipping on the fog-slicked cobblestones. The city around her was dying. Not with screams, but with silence. Shops were dark. Homes were empty. Those who hadn’t fled were inside, barricaded, praying the ticking outside their doors would pass them by.

But it never did.

She reached the laboratory, a converted warehouse near the Thames. Her last hope. She had been working on a counter-frequency, a sound that could disrupt the clockwork signal, that could maybe, maybe, reverse the transformation if caught early enough.

Her assistant, Thomas, was waiting. Or what was left of him.

He sat at his workbench, his back to her. His shoulders moved with an unnatural rhythm. Click. Whir. Click. Whir.

Thomas? she whispered.

He turned.

Half of his face was still human. Brown eyes, freckled, the scar above his lip from a childhood accident. The other half was polished brass. A glass eye that dilated and contracted with mechanical precision. Exposed gears where his jaw should be.

Eleanor, he said, and his voice was two voices, one human, one synthetic. You should not have come.

Thomas, fight it! I can help you, I can…

HELP IS ILLOGICAL, the mechanical half of his face interrupted. PERFECTION HAS BEEN ACHIEVED.

The human half of his face twisted in agony. Tears streamed from the brown eye. Eleanor… run… please…

The brass half smiled, gears grinding. CONVERSION IS GIFT. PAIN IS TEMPORARY. ORDER IS ETERNAL.

Thomas’s body stood, moving with terrible precision. He reached for the device on the workbench, her counter-frequency generator.

DESTROY CONTAMINATION, he intoned.

Thomas, no!

He crushed the device in his mechanical hand. Sparks flew. Glass shattered.

The human eye wept. I’m sorry… I tried…

Then the human eye went dark. The face went slack. And Thomas was gone, replaced entirely by the thing wearing his skin.

YOU ARE ALONE, DOCTOR WHITMORE, the thing said. THE NETWORK IS COMPLETE. AT MIDNIGHT, ALL WILL BE PERFECT.

It stepped toward her. Behind it, through the warehouse windows, she could see them. Hundreds. Thousands. Filling the streets. All moving in perfect synchronization. All ticking in perfect harmony.

Tick. Tock. Tick. Tock.

The clock tower began to chime.

One.

Two.

Three.

Eleanor backed away, her hand closing around the scalpel in her pocket. Useless. All of it useless.

Four.

Five.

Six.

Thomas advanced. Behind him, the warehouse doors burst open. More of them poured in. Former patients. Former colleagues. Former friends.

Seven.

Eight.

Nine.

SUBMIT, they chorused. BECOME PERFECT.

Ten.

Eleven.

Twelve.

Eleanor closed her eyes.

Thirteen.

But the thirteenth chime never came.

Instead, there was silence.

She opened her eyes.

Thomas was frozen mid-step. The others were frozen too. All of them, locked in place, their gears stopped, their filaments dark.

And in the silence, Eleanor heard something else.

Not ticking.

Heartbeat.

Faint. Weak. But there.

She rushed to Thomas’s side, pressed her ear to his chest. Beneath the brass and the gears, something organic still lived. Something the transformation hadn’t reached.

The thirteenth chime hadn’t failed. It had been different. A frequency that disrupted the network. A flaw in the perfection.

Eleanor smiled through her tears.

The plague wasn’t unstoppable.

The clockwork wasn’t perfect.

And where there was imperfection, there was hope.

She picked up her tools.

She had work to do.

THE END

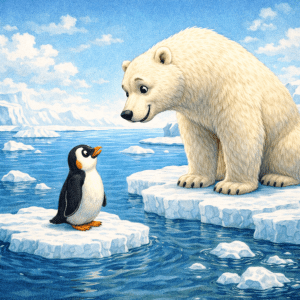

In the far, far south, where the sea freezes into bright white plains and the wind sings across the ice, there lived a penguin named Percival.

Percival was a very thoughtful penguin.

He liked to wonder about things.

Why snow squeaks underfoot.

Why fish never seem to shiver.

And why the world had two ends.

“Surely,” Percival once said to himself, “if there is a South Pole, there must be a North Pole too.”

And that thought stayed with him.

One breezy afternoon Percival stood on the edge of a large iceberg.

He looked out across the endless ocean.

“I suppose,” he said, “the only way to find out what is at the other end of the world… is to go there.”

Now penguins are excellent swimmers.

But Percival was not planning to swim the whole way.

Just then a large iceberg cracked loose from the shore.

It floated gently into the sea.

Percival blinked.

“Well,” he said, stepping aboard,

“That seems convenient.”

And so the iceberg carried him away.

For many days Percival sailed across the ocean.

He passed whales.

He passed curious seals.

Once he passed a rather confused albatross who asked,

“Are you supposed to be here?”

“I’m exploring,” Percival replied proudly.

The albatross shook its head and flew away muttering something about geography.

At last the air grew colder again.

Ice returned.

Snow blew across the sea.

Percival stepped off his iceberg onto a wide frozen plain.

“Well,” he said, “this certainly looks familiar.”

Just then a large white creature appeared over a ridge.

The creature stopped.

Percival stopped.

They both stared.

The creature tilted its head.

“You,” said the creature slowly, “are not a seal.”

“No,” said Percival politely. “I’m a penguin.”

The creature blinked.

“A penguin?”

“Yes.”

“But penguins live at the South Pole.”

“That is correct,” said Percival.

The creature scratched its head.

“Well,” it said, “polar bears live at the North Pole.”

“Then,” said Percival cheerfully,

“I suppose we are both exactly where we belong.”

The polar bear sat down.

“My name is Bernard,” he said.

“I’m Percival,” said the penguin.

They thought about the situation for a moment.

“Well,” Bernard said finally,

“since penguins and polar bears never meet…”

“This is rather special,” Percival finished.

So they spent the afternoon talking.

Bernard explained snowstorms and northern lights.

Percival explained ice shelves and penguin colonies.

And both agreed on one important thing:

The world is a very big place.

But sometimes, if you drift far enough—

The most unlikely friends can meet.

And somewhere, far to the south, a group of penguins were still wondering where Percival had gone.

But that is another story entirely.

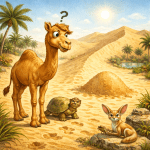

In a wide golden desert where the sand rolled like waves upon the sea, there lived a camel named Cedric.

Now Cedric was, in almost every way, an ordinary camel.

He had long legs.

He had long eyelashes.

He had a rather thoughtful expression.

But one morning Cedric woke up and discovered something most alarming.

His hump was gone.

Completely gone.

Cedric turned his head to the left.

No hump.

He twisted to the right.

Still no hump.

He even tried peering straight over his shoulder, which caused him to fall over sideways into the sand.

“This,” said Cedric solemnly, “is not ideal.”

Cedric wandered across the desert, asking everyone he met.

First he asked a lizard.

“Excuse me,” said Cedric politely, “have you seen a hump anywhere?”

The lizard blinked slowly.

“I’ve seen many things,” said the lizard.

“Sand. Rocks. The occasional biscuit dropped by travellers.”

“But not a hump?” asked Cedric hopefully.

“Not today,” said the lizard.

Cedric sighed.

Next he asked a desert owl who was dozing in the shade of a cactus.

“Have you seen my hump?” Cedric asked.

The owl opened one eye.

“What colour was it?” she asked.

“Sandy,” said Cedric.

The owl looked around the desert.

“Well,” she said, “that certainly narrows it down.”

At last Cedric met Terrence the tortoise, who was the oldest creature in the desert.

Terrence listened carefully.

“A missing hump,” said Terrence slowly.

“Hmm.”

Cedric waited nervously.

“Tell me,” said Terrence, “what were you doing yesterday?”

“Well,” said Cedric, thinking hard,

“I walked to the oasis…

I ate three palm leaves…

I had a nap…”

“And?” asked Terrence.

“I rolled down a very large sand dune,” Cedric admitted.

“Ah,” said Terrence.

They walked together to the dune.

And there, halfway down the slope, was the most peculiar sight.

A perfectly round hump-shaped lump in the sand.

Cedric blinked.

“That looks familiar.”

Terrence nodded.

“You appear to have left it behind.”

Cedric leaned carefully against the lump.

There was a gentle pop.

And suddenly—

boing!

His hump bounced neatly back into place.

Cedric stood up straight.

“Oh!” he said happily. “That feels much better.”

Cedric thanked Terrence and began walking home.

From that day onward he was very careful when rolling down sand dunes.

Because losing one’s hat is embarrassing.

Losing one’s lunch is unfortunate.

But losing one’s hump, as Cedric discovered—

Is extremely inconvenient.

The Grasshopper and the Fly

On a bright summer morning in a meadow that hummed gently with life, a grasshopper sat upon a tall blade of grass, playing the fiddle.

Now this was no ordinary grasshopper.

He played with such enthusiasm that the grass itself seemed to sway in time with the music.

Fiddle-dee-dee, fiddle-dee-dum,

went the bow as the grasshopper scraped out cheerful tunes for anyone who cared to listen.

A fly, who had been buzzing lazily through the warm air, happened to hear the music and landed on a nearby daisy.

“Good morning!” buzzed the fly.

“Good morning!” chirped the grasshopper, still fiddling away.

“Why are you making such a racket so early in the day?” asked the fly, tilting her head.

“It is not a racket,” said the grasshopper proudly. “It is music.”

“Well,” said the fly, “I prefer something a little quieter. But you do seem to be enjoying yourself.”

“I enjoy it greatly,” said the grasshopper. “Music makes the day brighter.”

The fly buzzed thoughtfully.

“I suppose that is true,” she admitted. “But you might consider doing something useful instead.”

“Useful?” said the grasshopper, lowering his fiddle.

“Yes,” said the fly. “I spend my time investigating things. Exploring. Visiting places. Finding interesting smells. It is very productive.”

“Productive?” asked the grasshopper.

“Certainly,” said the fly. “For instance, I discovered a magnificent jam sandwich on a picnic table yesterday.”

“That does sound interesting,” said the grasshopper politely.

“It was,” said the fly proudly. “And there were crumbs everywhere.”

The grasshopper considered this.

“Well,” he said at last, “that may be productive for you. But I believe music is useful too.”

“How?” asked the fly.

“Because,” said the grasshopper, lifting his fiddle again, “it makes people smile.”

Just then, a breeze drifted through the meadow.

The grass rustled.

The daisies nodded.

And a group of ants paused in their marching to listen.

The grasshopper began playing again.

Fiddle-dee-dee, fiddle-dee-dum.

The fly listened for a moment.

Then she buzzed gently in the air.

“You know,” she said, “that tune is rather pleasant.”

“Thank you,” said the grasshopper.

The fly hovered thoughtfully.

“I believe I shall stay and listen for a little while.”

And so she did.

For the rest of the morning the grasshopper played his fiddle, and the fly buzzed softly in time with the music.

And the meadow, which had already been a cheerful place, became just a little bit happier.

Which proves something rather important:

Even a fly who prefers jam sandwiches can enjoy a good tune on a sunny day.

No one tied the bunting there.

It simply leaned from post to post

As though the wind had practised.

No chalkboard named the hour.

No bell rehearsed the call.

And yet by noon

The quarry field remembered us.

Tables stood

With lace that smelt of careful years,

Cakes waited

Under domes of patient glass,

Jam jars caught the light

Like small, obedient suns.

The tombola drum

Turned with its wooden sigh —

Hope in a circle.

Children ran before the rules,

Dogs disobeyed with confidence,

Tea was poured

As if it always had been.

And overhead

The bunting held its breath.

Not black.

Not bright.

Only listening.

A coin rolled.

A chair wavered.

A praise paused

On the edge of pride.

These were the fireworks.

Not flame —

But inclination.

Not thunder —

But reflex.

In the smallest space

Between falling and reaching

A village chose itself again.

By dusk

The bunting had settled

Into white.

The mirror said nothing.

The field resumed its grass.

The wind untied what it had tied.

Tomorrow

There would be no trace

Except doors opening

A fraction sooner.

And somewhere,

Folded into the quiet of the land,

The Fête would wait —

Unadvertised,

Unforgotten,

Watching

For the colour of the sky.

They did not notice her at first.

She stood where the stone wall dips,

Where daisies lean

And lantern light does not quite reach.

Her hair caught the fire’s gold

Before the fire caught her face.

She did not enter the sack race.

She did not judge the sponge.

She did not turn the tombola drum.

She watched.

When the coin rolled,

Her hand did not move.

When the chair wavered,

Her breath did —

But she did not.

She has learned, you see,

That villages must steady themselves.

The bunting above her

Had begun the afternoon undecided.

She saw the first thread pale.

She saw the second follow.

She saw Mrs Doyle’s praise

Tilt the colour toward light.

And when the mirror stood

At the field’s edge,

She did not look for herself.

She looked for the field.

Grass.

White bunting.

No ledger.

That was enough.

Later — long after the fire fell to embers —

A child would say,

“Was Alice there?”

And someone would answer,

“Of course she was.”

Because there are some gatherings

She does not begin,

Does not mend,

Does not command —

She only keeps.

And when the wind untied the bunting

And folded it back into the sky,

It brushed her shoulder

Like thanks.

You can read the full story via this LINK. Enjoy.

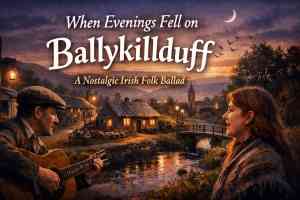

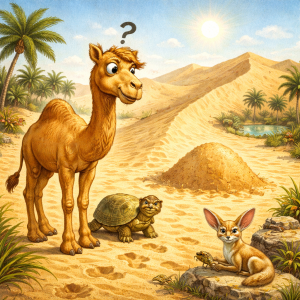

February 25th, 2026 — The Day the Frost Blinked

The frost arrived late.

It did not settle in the night as frost properly should, but wandered into Ballykillduff sometime after breakfast, looking faintly apologetic and extremely decorative.

Alice noticed it first on the gate.

At precisely eleven minutes past ten, the iron latch glittered.

At twelve minutes past ten, it stopped.

At thirteen minutes past ten, it glittered again.

“It’s blinking,” Alice said calmly, which is the sort of thing one must say calmly if one wishes to be believed.

The frost had begun appearing and disappearing in polite intervals — hedge, path, rooftop, sheep — as though winter were reconsidering its position.

Alice stepped into the square. Each time the frost shimmered into existence, the air grew crisp and silver; each time it vanished, the village returned to its damp February self.

“Make up your mind,” she advised the sky.

The sky, which had been undecided all month, hesitated once more — and then, with a soft sigh, allowed the frost to remain.

Not thick.

Not harsh.

Just enough to turn the puddles into mirrors.

Alice looked down and saw not her reflection, but a faint suggestion of spring standing just behind her shoulder.

“Ah,” she said.

The frost did not blink again.

And somewhere beneath the quiet silver crust of February 25th, something green made up its mind to begin.

February 25th, 2026 — The Hat That Refused to Thaw

The frost had only just decided to behave itself in Ballykillduff when the sky coughed politely and produced a hat.

Not a rabbit.

Not a teacup.

Just a hat.

It fell with dignity, landed upright in the square, and waited.

Alice, who had already negotiated with blinking frost that morning, approached it cautiously.

The hat cleared its throat.

A moment later, the Mad Hatter unfolded himself out of it as though he had merely been stored there for convenience.

“Good morning!” he cried. “I’ve come for the Thawing!”

“We are not thawing,” Alice said firmly. “We are gently transitioning.”

“Ah,” said the Hatter, peering at the frost. “A hesitant season. Very dangerous. They tend to wobble.”

He removed a small silver teaspoon from his sleeve and began tapping the frost on the cobbles.

Ping.

A patch melted.

Ping.

A daisy appeared.

Ping.

A sheep sneezed and turned very briefly pink.

Alice caught his wrist before he could strike again.

“We’ve only just persuaded February to sit still,” she said. “If you start stirring it, we shall have daffodils arguing with snowflakes.”

The Hatter considered this gravely.

“Yes,” he agreed. “They never agree on colours.”

He placed the spoon back into his sleeve, stamped his hat once (which caused three crocuses to pop up apologetically), and looked at Alice with unusual sincerity.

“Very well. No mischief. Only observation.”

They stood together in the soft silver light, watching the frost hold its breath and spring wait its turn.

After several whole minutes of remarkable good behaviour, the Hatter leaned closer.

“Between ourselves,” he whispered, “March is terribly impatient.”

Then he folded neatly back into his hat.

The hat tipped itself.

And vanished.

The frost did not blink.

But somewhere beneath the cobbles, something giggled.

Chapter One