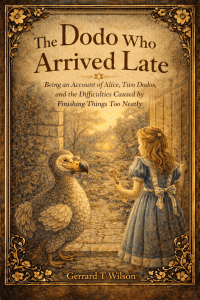

The Dodo Who Arrived Late

The Dodo Who Arrived Late

Being an Account of Alice, Two Dodos, and the Difficulties Caused by Finishing Things Too Neatly

A Brief Notice to the Reader

This story concerns a Dodo who should not have appeared,

an Aviary that preferred not to be visited,

and a girl who remembered slightly more than was considered advisable.

It is not a sequel, though it follows on.

It is not a correction, though it objects.

It does not resolve matters, but it does leave them ongoing.

Those seeking a tidy conclusion are advised to look elsewhere.

Those content with plural answers may proceed at their leisure.

Chapter I

In Which a Bird Long Thought Finished Makes an Error in Timing

No one noticed the Dodo at first.

This was partly because Wonderland has a habit of ignoring things until they become impossible to ignore, and partly because the Dodo himself arrived folded.

Not metaphorically folded, which would at least have been poetic, but actually folded — creased along the left wing, bent at the knees, and with his beak tucked in like an umbrella that had forgotten how to close properly. He fell from a sky that was not entirely certain it contained him and landed with a thump that was neither loud nor quiet but definitive.

The grass in the clearing stopped arguing with itself and looked offended.

The Dodo lay still for a moment, as though waiting for someone to announce that the fall had been a rehearsal.

No announcement came.

He unfolded slowly. First the beak. Then the wing. Then the solemn rearrangement of feathers, each one placed where it ought to be, as if appearance were a moral duty. Last of all he produced — from a place that did not appear to exist until he needed it — a small pair of spectacles and set them upon his nose.

He blinked at the world.

The clearing blinked back.

“Oh dear,” he said. “This is not Mauritius.”

The puddle beside him rippled with the faint air of disagreement, as puddles often do when overhearing geography.

The Dodo’s name (though he rarely used it aloud, having found that names caused expectations) was Professor Archibald Plume. He had once been a Dodo in the ordinary sense: a stout, sensible bird with a talent for walking as if one were late. Then he had been a Dodo in the historical sense: a symbol, a moral, a cautionary tale, and finally a blank space labelled Extinct.

He remembered the moment it happened, because he had been making notes at the time.

Extinction, he had concluded on the spot, was extremely bad for one’s schedule.

He could remember the beach. The salt. The heavy, human footsteps. The sensation of being measured by the future like an object that might be mislaid. He could remember the exact thought he had had — I should write this down, before it is decided for me — and how, as soon as he had thought it, reality had done the deciding.

It had shut like a book.

And yet here he was, in a place that felt like a margin.

The Dodo looked up through the branches. The sky above was pale and uncommitted, as though it had been painted once and then reconsidered. The trees leaned in the manner of listeners. The air smelled faintly of tea and punctuation.

He did not like it.

He liked, on the whole, things with clear origins and respectable endings.

A leaf floated down and landed on his head with the casual precision of an appointment. It was not an ordinary leaf. It had writing on it — not ink, exactly, but the impression of words that had been thought near it.

YOU ARE LATE, said the leaf, in polite capital letters.

“I beg your pardon,” said Professor Plume.

The leaf slipped off, spun in the air twice, and revised itself.

YOU ARE EARLY, it now announced.

Professor Plume stared at it.

The leaf grew flustered, which is difficult for a leaf but not impossible here.

YOU ARE… PRESENT, it decided at last, and promptly disintegrated with relief.

The Dodo made a small note on the back of his own feather (for he was the sort of creature who always had stationery, even when extinct).

Observation:

Time in this place is badly supervised.

At that moment, a distant bell rang, not because it had been rung but because it had remembered being rung before. The sound came from the trees, from the path, from the notion of elsewhere.

Professor Plume cleared his throat, picked up the dignity he had dropped during the fall, and began walking.

He did not yet know where he was going.

But then, neither did the path.

Chapter II

A Committee Is Formed, Which Solves Nothing

The first creature to find the Dodo was a Dormouse named Sleepwilliam, who was late for a nap and early for a meeting.

Sleepwilliam sat in a teacup that had been abandoned under a fern. He was asleep at first, then awake, then asleep again, as though practising the transitions. When he finally committed to awareness, he saw the Dodo and stared with one eye open.

“You’re not supposed to be here,” said the Dormouse.

“Yes,” said Professor Plume. “I have gathered that.”

Sleepwilliam blinked twice, as if using blinking to count.

“Are you a… thing?” he asked cautiously.

“I am a Dodo,” said the Dodo.

Sleepwilliam frowned.

“That’s not a thing,” he said. “That’s a warning.”

The Dodo hesitated. It is always unsettling to be described as a warning by someone who has barely woken up.

“I am,” he said carefully, “historically misplaced.”

Sleepwilliam considered this, then produced a small notebook titled Things I Have Woken Up To. He flicked through the pages. Most of them were blank, as though he preferred to keep his surprises unrecorded. There was an entry for “A Hat That Shouted,” another for “A Spoon That Would Not Admit It Was a Spoon,” and one alarming note that simply read Tuesday.

No mention of Dodos.

Sleepwilliam sighed, rang a tiny bell he carried for emergencies and birthdays, and fell asleep again out of habit.

Within minutes (which in Wonderland are not to be trusted), others arrived.

First came Mrs Quillip, a hedgehog librarian who catalogued thoughts that had not yet occurred. She wore spectacles on a chain and carried a keyring that rattled with the sound of locked explanations.

Then came Sir Bentworth the Reversible, a gentleman who could only walk backwards and therefore arrived facing the wrong direction with impressive confidence.

Then came Miss Tanglewick, a girl made entirely of ribbon, who unravelled slightly when surprised and tied herself together again when offended.

They stood in a semicircle (which is the shape committees begin as, before they become circles and then become nothing at all).

Mrs Quillip adjusted her spectacles.

“A Dodo,” she said.

Professor Plume bowed. “At your service.”

“But Dodos are extinct,” Mrs Quillip added, with the satisfied tone of someone quoting an index.

Professor Plume nodded. “Temporarily.”

Silence fell with the careful weight of a book being closed.

Sir Bentworth backed into a bush with authority.

Miss Tanglewick made a small knot of herself that signified concern.

“A committee,” said Mrs Quillip at once.

“A committee won’t help,” said Miss Tanglewick.

“That’s precisely why we need one,” replied Mrs Quillip.

And so, on the spot, the Committee for the Unexpected Persistence of Things That Are Supposed to Be Finished was formed.

Sleepwilliam snored gently in approval.

Mrs Quillip produced a clipboard that had not been there a moment before and wrote down the committee’s name in neat, decisive letters.

Sir Bentworth immediately nominated himself chair, then backed away from the responsibility because he could not face it.

Miss Tanglewick attempted to appoint minutes but kept tangling the minutes into bows.

“Now,” said Mrs Quillip briskly, “Mr Dodo. Explain how you are present.”

Professor Plume considered what could be said without making the situation worse.

“You see,” he began, “I was extinct.”

“That is not an explanation,” Mrs Quillip said.

“That is the beginning of one,” Professor Plume replied, and surprised himself by how firm his voice sounded.

Sleepwilliam opened one eye.

“Everything begins in the wrong place,” he murmured, and closed it again.

Professor Plume continued.

“I believe I fell through a crack between was and never again. I did not go where extinction intended. I went where things that do not belong are kept until someone decides what they mean.”

Mrs Quillip’s quills bristled.

“And you believe this… place… is where such things are kept?”

Professor Plume looked around. The trees leaned. The air waited.

“I believe,” he said, “this place is where decisions come to be delayed.”

Miss Tanglewick unravelled a little.

“That sounds like Wonderland,” she said.

Sir Bentworth, from inside the bush, asked politely if they could adjourn.

The committee agreed at once.

The clipboard vanished.

The committee dispersed with remarkable efficiency, as committees do when faced with actual work.

And Professor Plume was left alone again, with the Dormouse in his teacup and the sensation that someone, somewhere, had just written down his name and then underlined it.

From far away, through the trees, came shouting.

“Off with—oh bother—where did it go?”

Authority was approaching.

It always did, eventually.

Chapter III

The Dodo Explains Himself Badly, and Tea Arrives in Advance

The shouting grew louder, then grew confused, then became abruptly polite, as though someone had reminded it where it was.

A troop of playing-card guards marched into the clearing in a line that tried very hard to be straight but kept becoming decorative. They halted with a flourish that suggested they had practised.

Behind them came the Queen of Hearts, crimson and furious, followed by a small whirlwind of attendants, accusations, and misplaced confidence.

She stopped dead when she saw the Dodo.

Her eyes narrowed, not in the manner of suspicion but in the manner of someone trying to decide what category to be angry in.

“You!” she cried, pointing at him. “You’re late!”

Professor Plume bowed instinctively. “Madam, I—”

“Late!” the Queen repeated, as if the word itself were a sentence.

Sleepwilliam woke with a jolt.

“Everyone is late,” he said. “That’s why we’re here.”

The Queen ignored him.

Professor Plume tried again.

“Madam,” he said carefully, “I am historically misplaced.”

“Worse!” said the Queen. “Guards! Prepare—”

“No no no,” said a voice, bright and amused, and a table appeared where no table had been.

The Mad Hatter was sitting at it as if he had been waiting for the moment to become inconvenient. There were cups, saucers, a teapot with an anxious lid, and a spoon that kept trying to hide behind things larger than itself.

“Don’t behead him yet,” said the Hatter. “We haven’t decided what kind of error he is.”

The Queen glared.

“I decide errors,” she said.

The Hatter poured tea into a cup that screamed quietly.

“You decide punishments,” he corrected. “That’s different.”

The Queen looked offended by the distinction.

Professor Plume stared at the tea as though it might explain itself.

The Hatter grinned at him.

“Hello,” he said. “Are you an old thing that’s come back, or a new thing that’s pretending to be old?”

“I am,” said Professor Plume slowly, “a Dodo.”

“Yes,” said the Hatter. “But what sort?”

Professor Plume hesitated, then said the truth, which was a mistake but the only one available.

“I believe,” he said, “someone has been meddling with endings.”

At this, the tea table shivered. Not the cups — the idea of tea.

The Queen’s expression tightened.

“Meddling,” she repeated. “In my kingdom?”

The Hatter’s grin thinned.

“Oh dear,” he said. “He said the word.”

“What word?” demanded the Queen.

“The one that makes everything listen,” said the Hatter.

And indeed the trees leaned closer than before. The air seemed to hold its breath. Even the guards, whose faces were printed on them, looked momentarily blank.

Professor Plume felt it then: the sensation of being read.

As if an unseen finger had turned the page of the world and paused on him.

He swallowed.

“I should not exist,” he said, quieter. “But I do. Which means something failed. Or was altered.”

The Queen lifted her chin.

“Off with his—”

She stopped.

Her voice caught.

The command echoed, bounced, and returned wearing a question mark.

Nothing happened.

The Queen stared at her own mouth as though it had betrayed her.

“What,” she whispered, horrified, “have you done?”

Professor Plume took a step back. “Nothing, madam.”

“That,” said the Hatter, very softly now, “is the trouble. Something else has.”

The Queen’s cheeks flushed.

“My orders always work,” she said, too loudly.

“No,” said the Hatter kindly. “They usually try.”

The Queen drew herself up.

“Then we will find the thing that is interfering,” she declared. “And we will execute it repeatedly.”

“That sounds,” said the Hatter, brightening again, “like a plan that will accomplish nothing at all. Very Wonderland. I approve.”

Professor Plume felt cold.

Somewhere nearby, a feather drifted down, landed on the tea table, and formed words as it touched the wood:

REVIEW IMMINENT

The Hatter’s eyes flicked to it, then away.

Alice was not present.

Yet, oddly, Professor Plume found himself thinking of a girl he had never met, a girl who had once been a solution to a problem he did not yet understand.

He did not know why.

Wonderland, it seemed, was beginning to prepare.

Chapter IV

In Which Two Dodos Become One Problem Too Many

The trouble began when the second Dodo arrived.

He did not fall. He did not unfold. He did not apologise to the ground for landing on it. He was simply there, standing beside Professor Archibald Plume with the air of someone who had always been present and had merely been overlooked.

This Dodo was slightly shorter, marginally rounder, and carried a faint expression of administrative disappointment.

The Queen noticed at once.

“What,” she demanded, pointing with both hands this time, “is that?”

Professor Plume adjusted his spectacles.

“That,” he said carefully, “appears to be… me.”

“No, no,” snapped the Queen. “You are you. That is also you. This is intolerable.”

The second Dodo cleared his throat.

“If I may,” he said, “I am The Dodo.”

There was a pause.

“And I,” said Professor Plume, stiffly, “am a Dodo.”

The Queen’s eye twitched.

“Two Dodos?” she shouted. “In my Wonderland?”

“Historically speaking,” said the second Dodo, “I was here first.”

“That is correct,” said the Hatter, pouring tea into a teapot that immediately attempted to escape. “You organised the Caucus Race. Very circular. No clear winner. Excellent work.”

The second Dodo bowed modestly.

“I did what I could with the page space allotted.”

Professor Plume froze.

“Page space?”

“Oh dear,” said the Hatter. “He’s realised.”

They were brought — without walking — to a courtroom that looked suspiciously like a tea table with delusions of grandeur. The Queen sat upon her throne, glowering.

“There will be order!” she cried.

“No there won’t,” said the Hatter helpfully.

The Queen ignored him.

“You,” she said to the second Dodo, “explain yourself.”

The Dodo straightened.

“I am the Wonderland Dodo. I appear when things must go in circles, when no one is winning, and when the story requires an authority that accomplishes nothing.”

“Splendid description,” murmured the Hatter.

“And you,” snapped the Queen, turning to Professor Plume.

“I,” said Professor Plume quietly, “am the Extinct Dodo.”

A murmur rippled through the courtroom.

“You weren’t meant to exist,” said the Queen suspiciously.

“Correct,” said Professor Plume. “That is why I exist here.”

The Wonderland Dodo nodded.

“He fell through an ending.”

“Endings leak,” added the Hatter. “Everyone knows that.”

“So,” said the Queen slowly, “which one of you is real?”

Both Dodos spoke at once.

“I am.”

“I was.”

The Queen screamed.

“OFF WITH—”

She stopped.

Her command echoed, bounced, and returned wearing a question mark.

Nothing happened.

The Queen went pale.

“What have you done?” she whispered.

The Wonderland Dodo looked apologetic.

“You see,” he said, “there can only be one Dodo at a time.”

“And?” demanded the Queen.

“And,” said Professor Plume, “we appear to be overlapping.”

The Hatter clapped.

“Oh good! That means the story’s broken properly now.”

The courtroom dissolved into feathers, paper, and the sound of chapters being rearranged.

They found themselves before a vast iron gate, upon which was written:

THE AVIARY OF UNRESOLVED BIRDS

(No Conclusions Permitted)

Inside were creatures that should not still be there: a Phoenix that refused to burn; a Moa that kept asking what it had missed; parrots repeating sentences that were never finished.

“This,” said the Wonderland Dodo, “is where we keep things that were written once and should not have been.”

Professor Plume swallowed.

“And me?”

The Hatter leaned in.

“You’re not written yet.”

The Queen stared into the shadows.

“If this place exists,” she said, “what else might return?”

The gate creaked open further.

Something large shifted in the darkness, as if adjusting itself into the correct version.

Chapter V

In Which Alice Remembers One Dodo Too Clearly

Alice arrived the way she usually did now: by noticing.

She had been walking — she was fairly sure of that — along a path that kept changing its mind about whether it was a path at all, when the air grew thick with the sort of importance that generally meant something had gone wrong behind her back. She stopped, turned, and found herself at the open gates of the Aviary of Unresolved Birds.

She did not like the look of it.

Inside, feathers drifted as if unsure whether to land. A large bird coughed politely. Something else sighed as though it had been waiting a very long time.

And there, standing side by side, arguing quietly about chronology, were two Dodos.

Alice’s stomach did something unpleasant and immediate.

“No,” she said aloud.

Both Dodos turned.

The shorter, rounder one smiled with the calm satisfaction of recognition. The taller one adjusted his spectacles and looked anxious, as if he had been caught borrowing time.

The Hatter noticed Alice at once and beamed.

“Ah! There you are,” he said. “Perfect timing. Or dreadful. We haven’t decided.”

Alice did not look at him. She was staring at the Dodos.

“There was only one,” she said carefully.

The words did not echo. They pressed.

The birds exchanged glances.

“I remember you,” Alice said to the Wonderland Dodo. “You organised a race that went nowhere. Everyone won. I got wet.”

“Excellent summary,” said the Hatter.

Alice’s gaze slid — very reluctantly — to Professor Plume.

“And you,” she said, “are not him.”

Professor Plume bowed, deeply and respectfully.

“No,” he said. “I am what happened after.”

Alice felt cold.

“I don’t like this,” she said, which in Wonderland is a very serious objection indeed. “When I remember something, it usually stays remembered. Even when it shouldn’t.”

She rubbed her temple, where memories sometimes queued without permission.

“There is one Dodo in my head,” she continued. “He fits properly. He belongs to a race and a riverbank and a day that went in circles.”

She looked at Professor Plume again.

“You do not fit.”

Professor Plume nodded. “That has been my experience as well.”

The Wonderland Dodo frowned. “This is awkward.”

“It’s worse than awkward,” Alice said. “It’s wrong. When things don’t fit in Wonderland, they usually still pretend to. You’re not even pretending.”

The Queen swept forward, relief and fury warring on her face.

“You!” she cried, pointing at Alice. “Good. You remember how things are supposed to be.”

“Yes,” said Alice. “And this is not it.”

“Then order them removed!” demanded the Queen. “Off with one of their heads! I don’t mind which!”

Alice folded her arms.

“That won’t help.”

The Queen gasped. “She’s defying me politely.”

Alice stepped closer to Professor Plume.

“You’re not from my story,” she said quietly.

“No,” he agreed.

“But you’re not from now, either.”

He hesitated.

“I am from after the forgetting,” he said.

Alice stiffened.

“When things stop being told,” he went on, “they usually disappear. I did not.”

The Wonderland Dodo shifted uneasily.

“That’s not how it works,” he muttered. “Things end. That’s the rule.”

Alice looked between them.

“What if,” she said slowly, “someone has been reopening endings?”

The Aviary went silent.

Even the Phoenix stopped refusing.

The Hatter’s smile slipped, just a fraction.

“Oh dear,” he said. “She’s noticed.”

Alice straightened.

“If there are two Dodos,” she said, “then something has been tampered with. And if something has been tampered with, it’s going to keep happening.”

She looked directly at Professor Plume.

“You’re not a mistake,” she said. “You’re evidence.”

Professor Plume exhaled.

The Wonderland Dodo nodded reluctantly. “I suppose that makes me… precedent.”

The Queen crossed her arms. “I don’t like precedents.”

“No one does,” said the Hatter. “They lead to sequels.”

Alice turned toward the deeper shadows of the Aviary, where shapes shifted that should not have been waiting.

“Then we find out,” she said, “who is interfering with what ends.”

And for the first time since arriving, Wonderland did not contradict her.

Chapter VI

The Wing That Was Not For Visitors

The sign was the first thing Alice noticed.

It hung just inside the Aviary, nailed to nothing in particular, and read:

RESTRICTED WING

(Absolutely Not for Visitors)

Alice blinked.

The sign sighed and altered itself.

RESTRICTED WING

(Especially Not for Curious Girls)

Alice frowned.

“That settles it,” she said, and stepped forward.

Behind her, the Hatter made a delighted noise, the Queen made an outraged one, and both Dodos followed at different speeds for different reasons.

The air changed at once.

Here, the feathers did not drift. They waited.

The Restricted Wing was narrower than the rest of the Aviary and quieter, in the way that libraries are quiet when the books are listening. The walls were lined with tall shelves, each holding cages, boxes, drawers, and frames. Every item bore a label written in a careful, apologetic hand.

Alice read the nearest one.

A SONG THAT WAS HUMMED ONCE AND THEN FORGOTTEN

Inside the cage sat a small bird made entirely of notes. It opened its beak, but no sound came out. The notes rearranged themselves instead, as though trying to become acceptable.

Farther along:

A CAT WHO WAS TO HAVE VANISHED MORE SLOWLY

A faint grin hovered in a glass case, looking offended.

“This place smells like editing,” said the Hatter softly.

Alice stopped.

Editing was a word she did not like in Wonderland.

They came to a table where three figures sat together, as though placed there for comparison.

The first was a boy with ink-stained fingers and no shadow at all. He waved cheerfully.

“I was going to ask a question,” he said, “but it was decided I asked too many.”

The second was a woman made of clockwork lace. Her chest ticked irregularly.

“I was meant to arrive late,” she said. “Instead, I was removed early.”

The third was a creature that might have been a bird or might have been a punctuation mark. It shifted nervously.

“I was a semicolon,” it said. “But no one could agree what I was joining.”

Alice swallowed.

“You’re not mistakes,” she said.

The three nodded at once.

“That’s what we keep saying,” replied the boy. “Mistakes get erased. We were organised.”

Professor Plume’s feathers bristled.

“This is not extinction,” he whispered. “This is curation.”

At the far end of the wing stood a tall cabinet of drawers. Each drawer bore a number, though some had been scratched out and rewritten several times, as if the cabinet itself had changed its mind about counting.

Alice pulled one open.

Inside lay a stack of index cards tied with red string.

Each card held a name.

Some were crossed through. Some were annotated. Some had question marks beside them, multiplying.

At the bottom of the stack lay one card turned face down.

Alice hesitated, then flipped it.

Her own name stared back at her, written neatly, with a note beneath.

Status: Ongoing

Interference Not Advised

The Queen gasped.

The Hatter stopped smiling.

The Wonderland Dodo sat down very suddenly.

Professor Plume read the card twice.

“Oh,” he said. “That explains the falling.”

Alice closed the drawer.

“So,” she said slowly, carefully, “someone has been sorting Wonderland.”

No one contradicted her.

“Not fixing it,” she continued. “Not improving it. Tidying it. Deciding what fits and what doesn’t.”

She looked at the shelves, the cages, the drawers.

“And Wonderland,” she said, “has been letting them.”

From somewhere beyond the shelves came the faint sound of paper being turned.

Slowly.

Deliberately.

Someone else was in the Aviary.

Chapter VII

The Archivists of What Was Never Finished

They did not announce themselves.

They never did.

The sound Alice had heard — paper turning — came again, closer now, followed by the soft, precise cough of someone who wished to be noticed only after everything was already decided.

From between two towering shelves stepped three figures.

They were dressed alike, though no two of them matched. Each wore a long coat the colour of old pages, stitched with pockets that bulged with notes, tags, and slips of ribbon. Their faces were calm in the way of people who believed calm to be a form of authority.

The tallest inclined his head.

“We are the Archivists,” he said, as if explaining something Alice ought already to know.

“Specifically, the Archivists of What Was Never Finished.”

The second Archivist smiled kindly.

“You may think of us as caretakers.”

The third adjusted her spectacles.

“Or editors.”

Alice felt something in the air tighten.

“You shouldn’t be here,” said the first Archivist, consulting a ledger. “But then again, you never are.”

“That’s true,” said Alice. “I don’t usually try.”

The Archivists exchanged a look that suggested this was precisely the problem.

“We exist,” said the second, “because stories are messy.”

“Things begin and then refuse to end,” added the third. “Characters linger. Ideas echo. Extinction fails to finish its work.”

Professor Archibald Plume flinched.

“We prevent that,” said the first Archivist gently. “We catalogue. We contain. We ensure continuity.”

“Continuity of what?” Alice asked.

The Archivist paused, surprised.

“Why,” he said, “of coherence.”

Alice walked past them, running her fingers along the shelves.

“You’ve kept things that were never mistakes,” she said. “You’ve locked away possibilities.”

“Possibilities are dangerous,” replied the third Archivist. “They spread.”

The Hatter leaned in.

“So does tea,” he said. “But you don’t see us shelving that.”

The Archivists ignored him.

“Wonderland,” said the second, “was becoming unstable. Too many loops. Too many returns.”

He gestured at the two Dodos.

“This,” he said, “is what happens when endings are left unattended.”

The Wonderland Dodo bristled.

“I did my duty,” he said stiffly. “I concluded a race.”

“Yes,” said the Archivist. “But you concluded nothing else.”

Professor Plume stepped forward.

“And I?” he asked.

The first Archivist looked almost regretful.

“You are an oversight,” he said. “A remainder. Extinction should have resolved you.”

“And yet,” said Alice, “it didn’t.”

“No,” agreed the Archivist. “Which is why we are correcting it.”

The first Archivist opened his book.

“Now,” he said, “we must attend to the overlap.”

The pages turned themselves, stopping at an entry marked with a feather pressed flat between sheets.

DODO

Status: Redundant

Action: Consolidate

Alice’s heart thumped.

“What does ‘consolidate’ mean?” she asked.

The Archivist smiled.

“It means,” he said, “there will be one Dodo again.”

The two Dodos looked at one another.

“One of us goes?” asked Professor Plume.

“Not exactly,” said the second Archivist. “You will be merged. Simplified. Reduced to a function.”

The Wonderland Dodo swallowed.

“I don’t want to be simplified,” he said.

Alice stepped between them and the Archivists.

“You can’t,” she said.

The first Archivist frowned.

“We can,” he replied. “This is our purpose.”

Alice shook her head.

“No,” she said, very calmly. “This is your habit.”

The Archivists closed their ledger.

“We will discuss this,” said the first. “Later.”

They began to retreat, already fading into the shelves.

“This is not over,” said the second Archivist.

“No,” said Alice. “It isn’t.”

But as they vanished, Alice noticed something dreadful.

Her card —

Status: Ongoing —

had acquired a new note, written in fresh ink.

Review Imminent

Alice did not like the sound of that at all.

Chapter VIII

The Day the Dodos Began to Agree

At first, it was only a feeling.

The sort one gets when a sentence is about to repeat itself but cannot quite remember how it began.

Professor Archibald Plume noticed it while adjusting his spectacles. They slid slightly too far down his beak, as though gravity had briefly misjudged where his face ought to be. He pushed them back up and frowned.

“I appear,” he said, “to be remembering something I never experienced.”

The Wonderland Dodo looked up sharply.

“Oh dear,” he said. “That’s mine.”

They stared at one another.

“I remember,” said Professor Plume slowly, “standing on a riverbank. Organising a race. Declaring everyone a winner.”

The Wonderland Dodo’s feathers fluffed in alarm.

“But that’s me.”

“Yes,” said Professor Plume. “That’s the problem.”

Alice felt it then too. A subtle tug behind her eyes, as if two similar thoughts were being gently pressed together.

“No,” she said. “Stop that.”

Neither Dodo was touching the other. Yet the space between them had grown thinner.

The Aviary shuddered.

Shelves creaked. Labels fluttered. The semicolon creature squeaked and hid behind a crate marked ALMOST IMPORTANT.

The two Dodos stepped apart instinctively — and found that the step did not fully separate them.

Their shadows overlapped.

Worse still, the shadows argued.

“I am the original,” said one shadow.

“I am the remainder,” said the other.

The Hatter clapped.

“Oh this is very bad,” he said cheerfully. “They’re agreeing.”

“What happens when they agree?” asked Alice.

The Hatter tilted his head.

“Usually? Simplification.”

Outside the Aviary, Wonderland adjusted itself.

Paths doubled back incorrectly. A tree grew a second trunk, decided it was unnecessary, and apologised. A clock struck tea-time twice and then refused to continue.

The Queen’s voice echoed from somewhere beyond the Restricted Wing.

“My orders,” she cried, “are coming out shorter!”

Professor Plume gasped.

“I am losing details,” he said. “My name feels… optional.”

The Wonderland Dodo nodded gravely.

“I have always been mostly a function,” he said. “But you — you had a before.”

Alice stepped forward.

“Don’t let them,” she said. “Don’t finish each other.”

The Dodos looked at her.

“That may not be a choice,” said Professor Plume gently. “When two versions occupy the same conclusion, one must be edited.”

Alice felt a strange relief press against her thoughts.

A smoothing.

A trimming.

She staggered.

The Hatter caught her elbow.

“Careful,” he said softly. “They’re having a go at you too.”

Alice frowned.

“No,” she said. “They’ve already been here.”

She closed her eyes and remembered a hesitation long ago — a question she meant to ask but didn’t. A moment when Wonderland almost explained itself and then decided not to.

She opened her eyes.

“I’ve been edited before,” she said.

The Hatter did not deny it.

“You were getting a bit sharp,” he said kindly. “Asking questions with edges.”

Alice clenched her fists.

“And if you merge,” she said to the Dodos, “there will be peace.”

“Yes,” said the Wonderland Dodo, softly. “But it will be smaller.”

Alice stepped between them and placed a hand on each.

“Wonderland doesn’t need fewer things,” she said.

“It needs braver endings.”

Somewhere deep in the Aviary, a ledger snapped shut.

The Archivists had noticed.

Chapter IX

In Which Alice Is Shown What She Used to Be

The Archivists did not return by walking.

They returned by remembering the room incorrectly.

One moment the Restricted Wing was lined with shelves; the next, those shelves had always been desks. Lamps appeared that had never been lit, and papers lay waiting that had not yet been written. The air smelled of ink, dust, and certainty.

“You came back quickly,” Alice said.

“When something resists consolidation,” said the first Archivist, “it must be reviewed.”

“Reviewed,” Alice repeated. “Is that what you call it?”

“It is a kindness,” said the second.

The third opened the ledger. Its pages glowed faintly, as if lit from behind by a memory trying to escape.

“Before we proceed,” he said, “it is only fair you understand your history.”

“I understand my history,” said Alice.

“You understand the published version,” said the Archivist.

The ledger turned itself to a page marked with a small teacup pressed flat like a flower.

ALICE

Initial Status: Variable

Function: Inquiry

Risk Assessment: Escalating

Alice felt a tightening behind her eyes.

“You were never meant to be comfortable,” said the first Archivist.

“That sounds like Wonderland,” said Alice.

“Yes,” said the Archivist. “But you were becoming… directional.”

The pages shimmered, and the room altered.

Alice watched a younger version of herself — smaller, sharper-eyed — standing in a place that had no name because it had never been allowed to keep one.

That Alice asked questions that did not stop.

Why did the Queen rule?

Why did time obey tea?

Why did endings exist at all?

“Do you remember this?” asked the second Archivist.

“I remember asking questions,” said Alice.

“Not like that,” said the third.

In the vision, the younger Alice pressed. She returned to questions that had been dismissed. Wonderland around her grew uneasy — paths hesitated, words stumbled, logic began to show seams.

“She was close,” said the first Archivist quietly. “Too close.”

“To what?” asked Alice.

“To understanding that Wonderland does not happen,” said the second. “It is maintained.”

The vision shifted.

A pause.

A soft adjustment.

A moment where Alice nearly asked one question too many — and then did not.

Alice felt it like a bruise.

“You edited me,” she said.

“We refined you,” replied the first Archivist. “You remained curious, but no longer invasive.”

The ledger showed a neat annotation.

Revision Applied:

Wonder → Retained

Persistence → Softened

Memory Depth → Limited

Alice opened her eyes.

“I want it back,” she said.

The Archivists stiffened.

“You cannot,” said the first. “The revision is stable.”

“I’m not asking,” said Alice. “I’m remembering.”

The ledger trembled.

Somewhere in the Aviary, a cage opened itself.

The two Dodos cried out at once — one in fear, one in relief — as their overlap surged and then steadied, held by something firmer than consolidation.

Alice felt it settle into her bones: not answers, but permission to keep asking.

“This,” she said, “is what you were afraid of.”

“For the record,” said the second Archivist, “yes.”

Alice placed her hand upon the ledger.

“And you,” she said, “don’t get to decide what I am anymore.”

The pages went blank.

Outside, Wonderland exhaled.

Not relief.

Expectation.

Chapter X

The Consolidation That Would Not Hold

The Archivists tried one last time.

They did not shout. They did not threaten. They simply proceeded, which is far more dangerous.

The ledger reopened. Pages slid into place. Margins straightened. Footnotes gathered themselves like well-behaved children. The lamps steadied. The air smelled sharply of order.

“We will complete the consolidation,” said the first Archivist. “It is overdue.”

At the centre of the Restricted Wing, the two Dodos stood so close that their outlines blurred.

“Ready?” asked the Wonderland Dodo, trying to sound official.

Professor Plume adjusted his spectacles. “As one ever is.”

Alice stepped forward.

“No,” she said.

The word stuck.

The Queen arrived with a stamp — large, red, and shaped like a heart that had learned to disapprove. She slammed it down on a sheet that appeared just in time.

“I DECLARE,” she shouted, “THAT NO ONE IS TO BE SIMPLIFIED WITHOUT MY EXPRESS PERMISSION.”

She stamped again.

“AND I PERMIT NOTHING.”

The Archivists blinked.

“This decree is imprecise,” said the second Archivist.

“It is royal,” snapped the Queen. “That makes it binding and useless at once.”

The paper attempted to organise itself, failed, and burst into confetti.

The Hatter hopped onto a desk.

“I should like to add a footnote,” he said cheerfully. “All consolidations must include tea.”

A teapot appeared. It poured itself. The ledger recoiled.

“Tea,” the Hatter continued, “is famously unconsolidatable.”

Alice stood between the Dodos again, one hand on each shoulder.

“You want one Dodo,” she said to the Archivists. “You think one is cleaner.”

“Correct,” said the first Archivist.

“Then watch,” said Alice.

She closed her eyes — not to forget, but to remember differently.

“Professor Plume,” she said softly, “you are not required to end.”

He straightened, startled. “I am not?”

“And you,” she said to the Wonderland Dodo, “are not required to explain.”

The Wonderland Dodo seemed to breathe out centuries of obligation.

“Oh,” he said. “That is a relief.”

“You are not the same thing,” said Alice. “You are not competing. You are adjacent.”

The space between them widened — not by force, but by permission.

The ledger shuddered.

“There must be a single entry,” said the third Archivist.

“There will be,” said Alice. “Just not the one you want.”

The page rewrote itself.

DODO

Status: Plural

Function: Inconclusive

Action: Continue

Ink spread, hesitated, and settled.

The overlap dissolved. Two shadows separated and bowed to one another.

Professor Plume laughed — soft, astonished. “I remain.”

The Wonderland Dodo nodded, dignified. “And I recur.”

Outside the Aviary, Wonderland steadied. Paths chose directions again, though not always the same ones. A clock resumed, then immediately stopped for tea.

“This cannot be allowed,” said the first Archivist, but his certainty had thinned.

“It has already happened,” said Alice.

The ledger snapped shut.

“We will escalate,” warned the second.

“Do,” said Alice pleasantly. “Bring more paper.”

The Archivists faded — not erased, but deferred, which annoyed them greatly.

The Queen sniffed.

“I don’t like this outcome.”

“No one does,” said the Hatter. “That’s how you know it’s working.”

Alice looked around at the cages opening, the labels loosening, the unfinished beings stretching like sleepers waking.

She felt different. Not fixed. Not free.

Ongoing.

“That,” she said quietly, “will do.”

Wonderland did not argue.

It adjusted.

Epilogue

In Which Nothing Ends, Properly

Alice left the Aviary without leaving it.

This was not difficult. One simply walked away while remaining, which Wonderland permits so long as one does not make a point of it.

The morning — if it could be called that — was pale and undecided. Light rested on things without committing to them. Somewhere behind her, a cage door swung gently and then decided it had always been open.

Alice walked along a path that did not ask where she was going.

Ahead of her, two Dodos walked the same direction but not together.

Professor Archibald Plume stopped to examine a leaf that looked like a footnote. He made a small note of it on a scrap of paper that promptly forgot why it was written. The other Dodo continued on, nodding to a passing hedgehog, already preparing for a race that might never quite begin.

They did not merge.

They did not fade.

They simply continued.

Alice smiled.

At the edge of the path stood a sign.

It read:

THIS WAY TO THE END

Alice paused. The sign hesitated.

The words rearranged themselves.

THIS WAY TO AN END

She took another step. The sign sighed deeply and changed again.

THIS WAY (FOR NOW)

“That seems fair,” Alice said.

She walked on.

Behind her, somewhere far away, a ledger lay closed. Not sealed. Not destroyed. Simply unused, as ledgers so often are when things insist on happening anyway.

Wonderland stretched, yawned, and allowed a few more questions than usual to remain unanswered.

Which was, after all, how it preferred things.

And if, later, someone were to say that the story had ended —

Well.

That would only mean it had chosen to continue elsewhere.

THE END

(Provisionally)

Blurb

A Dodo has arrived in Wonderland.

This would not ordinarily be remarkable—except that Dodos are extinct, and this one is late.

When a second Dodo appears, insisting he has always been there, Wonderland begins to misbehave in subtle and alarming ways. Paths hesitate. Endings loosen. And Alice, who remembers only one Dodo very clearly, finds herself drawn into an Aviary where unfinished things are kept neatly out of sight.

As polite, reasonable Archivists attempt to tidy what was never meant to be finished, Alice must decide whether stories are improved by being completed—or whether some things are better left ongoing.

Witty, unsettling, and quietly defiant, The Dodo Who Arrived Late is a new Wonderland tale about memory, plurality, and the dangers of finishing things too neatly.

About the Author

Gerrard T Wilson writes whimsical, Carroll-adjacent fiction in which logic misbehaves, authority is questioned politely, and stories have a habit of continuing elsewhere. His work often explores forgotten corners, unfinished ideas, and characters who arrive slightly out of time.