Alice in Ballykillduff and the Almost-Remembered Tartaria

Alice in Ballykillduff and the Almost-Remembered Tartaria

Chapter One

In Which the Grass Takes a Position and Ballykillduff Misplaces Itself

It is a curious thing, and not often admitted aloud, but Ballykillduff was the sort of village that behaved as though it had ideas.

Not grand ideas. Not political ones. Ballykillduff did not stand on soapboxes and announce opinions to passing carts. It preferred its thinking quiet and sideways, in the manner of a kettle deciding to whistle a moment before it boiled, or a gate choosing to stick only when someone important approached.

The village was full of small decisions that nobody remembered making.

A lane would curve, not because it was built that way, but because it had reconsidered. A hedge would grow in a slightly more defensive shape than the season required. A postman would arrive at the correct house by the wrong route and never once suspect anything unusual had occurred.

Alice had noticed these things for some time.

She was not originally from Ballykillduff, which is the sort of detail Ballykillduff tolerated as long as nobody spoke too loudly about it. She had been there long enough to be treated as nearly ordinary, which in Ballykillduff was considered the highest compliment available.

On the morning this story begins, Alice had been sent on an errand that was meant to be simple.

She was to bring eggs to Mrs Gaffney and, if she had time, to call at the Old Creamery to see if anyone knew why its chimney had been smoking in a suspiciously thoughtful manner.

Mrs Gaffney’s eggs were in a basket on Alice’s arm. There were three of them, because Ballykillduff preferred odd numbers. Even numbers tended to look too finished.

Also in the basket was a jam sandwich, wrapped in paper, and a question Alice had been carrying since Tuesday.

The question was not written down. It was merely present, like a pebble in a pocket, and it had been troubling her because it refused to become a proper question. It was more of a half-question. A question with its hat on backwards.

Why did Ballykillduff sometimes feel as though it was waiting for something?

Alice was considering this when she found herself behind the Old Creamery.

She had not meant to go there. The lane had offered the turn with such confidence that she took it without noticing she had done so.

It was quiet behind the Creamery. Not the usual quiet of birds and distant voices, but a quieter quiet, arranged and deliberate, like the pause before someone reveals a secret.

The grass was leaning.

Not blown by wind. Not bent by weight. It leaned as though listening, toward a particular patch of ground where nothing at all appeared to be happening.

Alice stared at it.

“Do stop that,” she said.

The grass leaned a little further.

The air in front of her creased.

This is difficult to describe without folding the reader, but imagine a page in a book that has been turned too often and has developed a permanent bend. Now imagine the world doing the same thing.

There was a sound like paper being rearranged.

And where there had been nothing, there was now a sign.

It stood on two posts that looked faintly surprised to be involved. The paint was neither fresh nor peeling, but in a state of having once been remembered vividly and then forgotten politely.

It read:

TARTARIA

(FORMERLY ELSEWHERE)

Alice read it twice.

“Formerly where?” she asked.

The letters shuffled.

A second line appeared.

HERE,

BUT YOU WERE BUSY THEN

“I do not remember being busy enough to miss an entire country,” Alice said.

The ground beneath her boots dipped.

Not collapsed. Not opened. It dipped in the manner of a courteous bow.

Alice slid.

Not fell.

The Old Creamery withdrew behind her discreetly. The grass straightened. Ballykillduff, having done something impossible, immediately pretended it had done nothing at all.

Chapter Two

In Which Forgetting Is Explained, Taught, and Found to Be Unreliable

Alice arrived in Tartaria with the uncomfortable sensation of being placed in the wrong drawer.

She stood on a wide avenue paved with stone that shimmered faintly, as though it remembered being important. Domes rose ahead like inverted teacups, humming softly, not musically but administratively.

Everything was calm.

Not peaceful. Calm suggested rules.

Lampposts glowed faintly in daylight. Each bore a plaque.

HERE

STILL HERE

HERE, FOR NOW

Alice frowned at the last.

Ahead stood a building that looked like a school, though it had clearly been constructed by someone who distrusted permanence.

The walls were chalk. The roof was chalk. Even the steps were chalk, though they appeared proud of holding together.

Above the door:

THE ACADEMY OF NECESSARY FORGETTING

The door opened.

“Well?” said a sharp voice. “Come in or don’t, but decide. Hesitation causes dreadful gaps.”

Alice went in.

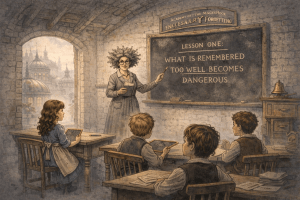

Inside, children stared at their hands. At the front stood a woman with hair like a startled hedgerow and spectacles that looked permanently unimpressed.

“I am Miss Bramblehook,” she said. “Sit down and forget something.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Excellent,” said Miss Bramblehook. “Lesson One.”

She wrote:

WHAT IS REMEMBERED TOO WELL BECOMES DANGEROUS

“Tartaria vanished because it behaved too well,” Miss Bramblehook explained. “Nothing squeaked. Nothing collapsed. Nobody argued.”

“Civilisations require at least three small disasters,” she added. “And one embarrassing disagreement.”

Alice raised her hand. “If Tartaria vanished, how are we here?”

Miss Bramblehook underlined a word.

IMPERFECTLY

“We were remembered wrongly,” she said. “And that saved us.”

The idea of a bell passed through the room.

“Forget what you have learned,” said Miss Bramblehook.

Outside, Alice met a small man polishing the base of a bell tower with no bell.

“I am Old Nearly,” he said cheerfully. “Caretaker of Things That Almost Happened.”

“Why am I here?” Alice asked.

“Because you remember things slightly wrong,” said Old Nearly. “And we need that.”

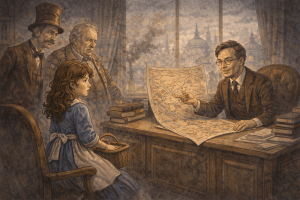

They stopped at a map etched into the ground.

It was wrong.

At its centre was a blank space.

“That,” said Old Nearly, “is where you come in.”

Chapter Three

In Which the City Holds a Meeting, and Alice Is Found to Be Inconvenient

The street forked into too many directions.

A signpost rotated its arms.

“You have been noticed,” it said.

The ground slid sideways.

Alice found herself in a circular chamber filled with people sitting in chairs that faced different times.

THE COUNCIL OF INCONVENIENT CERTAINTIES

Madam Parallax leaned forward. Professor Slant leaned left. A thin man flickered.

“She is a witness.”

“She is a distortion.”

“She is imaginary.”

Alice blinked.

“You are very good at remembering things wrongly,” Old Nearly whispered.

Tartaria, the Council explained, was being remembered again. Incorrectly. Maps were twitching. Scholars elsewhere were writing notes they did not understand.

“We must be remembered,” said Madam Parallax. “But not neatly.”

“You will carry us,” they told Alice. “In stories. In contradictions.”

“And if I refuse?”

“Then Tartaria will remember itself,” said Old Nearly quietly.

“That never ends well.”

Chapter Four

In Which Geography Objects, and Alice Is Chased by Certainty

The map appeared.

Not folded. Not pinned. Upright and offended.

At its centre was a pulsing mark.

“That is you,” said Old Nearly.

The street lurched.

“Run,” said Old Nearly.

Alice ran.

The map corrected the city behind her. Streets contradicted her feet. Lampposts relabelled themselves.

She collided with Mr Quillip Spoke, pushing his desk.

“You have existed imprecisely,” he said. “Maps hate that.”

The basket tugged.

Inside was a note:

DO NOT LET IT FINISH

Alice lied to the map.

“This is not where I am.”

The map hesitated. Lines wavered. The mark split.

They escaped.

“Tartaria is remembering you incorrectly,” said Mr Spoke.

“That sounds worse,” said Alice.

“Oh yes,” said Old Nearly. “Much worse.”

Chapter Five

In Which Explanations Begin to Arrive, and Alice Learns That Being Understood Is a Risk

Alice dreamed of arguing maps.

The domes hummed anxiously.

Mr Spoke arrived in a hurry.

“Outside has asked questions,” he said. “Sensible ones.”

A new building appeared.

Inside sat Dr Percival Index, tidy, confident, exact.

“This is what Tartaria ought to be,” he said, showing a neat map.

“That is why it is wrong,” Alice replied.

“If we explain you,” said Dr Index, “we will know where to put you.”

“Tartaria survives because it is unfinished,” Alice said. “If you explain it properly, it will be over.”

Dr Index frowned.

“You are not merely a witness,” he said. “You are a distortion.”

Outside, a footnote expanded into a paragraph.

And Alice understood that being chased was one thing.

But being explained was far worse.

Of course.

Here is Chapter Six, written to continue seamlessly from Chapters One to Five, deepening the stakes and marking the moment when Tartaria stops reacting and begins to act with intent.

Chapter Six

In Which Tartaria Attempts Containment, and Alice Is Asked to Be Sensible

Alice was not arrested.

This distinction mattered to Tartaria.

She was contained.

The difference, as Mr Quillip Spoke explained while wheeling his desk briskly beside her, was largely one of tone.

“Arrest implies blame,” he said. “Containment implies concern.”

“I feel blamed,” Alice replied.

“Yes,” said Mr Spoke. “That does happen.”

They passed through streets that were behaving unusually well. Too well. Windows aligned themselves. Doorways remained where they were told. Even the air seemed cautious, as though afraid of improvising.

This, Alice suspected, was far worse than chaos.

“Is this because of Dr Index?” she asked.

Mr Spoke winced. “Partly. Also because Tartaria has reached a conclusion.”

“That sounds serious,” said Alice.

“It is,” Mr Spoke replied. “Tartaria does not often reach conclusions. It prefers ellipses.”

They stopped before a building Alice was certain had not existed until that moment.

It was perfectly square.

That alone was alarming.

The walls were smooth, the corners precise, the windows evenly spaced. No hum emanated from it at all.

Above the door was a plaque that did not flicker, smudge, or apologise.

THE DEPARTMENT OF TEMPORARY STABILITY

Alice stared at it.

“I do not like the look of that,” she said.

“Nor does anyone who enters,” Mr Spoke replied cheerfully. “But please remember, it is only temporary.”

The door opened.

Inside, everything was beige.

Not warmly beige. Not comfortingly beige. This was the sort of beige that had been chosen because it offended no one and delighted absolutely nobody.

The room contained a table, several chairs, and a woman arranging papers with unnecessary precision.

She looked up as Alice entered.

“Ah,” she said. “You must be Alice.”

“I must?” Alice replied.

“Yes,” said the woman. “We have decided so.”

“I am Ms Ledgerly,” she continued. “Senior Officer in Charge of Holding Things Still Until Further Notice.”

Old Nearly stood near the wall, looking profoundly uncomfortable.

“You promised no corners,” he muttered.

Ms Ledgerly smiled without warmth. “We rounded them. Minutely.”

Alice sat down because the chair had already decided she would.

“We have reviewed your situation,” Ms Ledgerly said. “You are causing narrative instability.”

“I have been told that before,” Alice said.

“Yes,” said Ms Ledgerly. “But now it is official.”

She slid a document across the table.

It was blank.

“That,” said Ms Ledgerly, “is your agreement.”

Alice blinked. “I cannot sign nothing.”

“Precisely,” said Ms Ledgerly. “You agree to do nothing further.”

Mr Spoke coughed politely.

“The proposal,” he explained, “is that you remain here, comfortably, while Tartaria settles.”

“And if I do not agree?” Alice asked.

Ms Ledgerly tapped the table.

“Then Tartaria will attempt to resolve you.”

Alice felt a chill.

“Resolve me into what?” she asked.

Ms Ledgerly smiled again. “That is under discussion.”

Alice glanced around the room.

The walls did not hum. The air did not crease. Nothing leaned.

“This place is too neat,” Alice said.

“Yes,” said Ms Ledgerly. “That is the point.”

Old Nearly shifted from foot to foot. “She will not fit,” he said quietly.

“We are aware,” Ms Ledgerly replied. “That is why we are trying to make her.”

Alice looked at the blank agreement.

“If I stay,” she said slowly, “you will stop explaining Tartaria?”

“For a time,” said Ms Ledgerly.

“And if I leave?”

Ms Ledgerly hesitated.

“That would be unhelpful.”

Alice stood.

At once, the room reacted.

The corners sharpened. The beige deepened. The table lengthened slightly, as though preparing to block her path.

“Please sit,” said Ms Ledgerly firmly. “Sensible behaviour will be rewarded.”

Alice shook her head.

“Tartaria survives by being unfinished,” she said. “You cannot contain that.”

Ms Ledgerly’s expression tightened.

“We are not containing Tartaria,” she said. “We are containing you.”

The walls creaked faintly.

Somewhere outside, a dome hummed in protest.

The basket tugged at Alice’s arm.

She looked inside.

The eggs were still there. The jam sandwich was gone. In its place lay a small folded card.

It read:

MISREMEMBER ME

Alice smiled, slowly.

“That,” she said, “seems reasonable.”

She stepped sideways.

Not forward. Not backward.

Sideways.

The room shuddered.

The beige cracked.

The table forgot how long it was.

Ms Ledgerly gasped. Mr Spoke dropped a stamp. Old Nearly beamed.

Alice did not disappear.

But the room did.

When it returned, it was no longer square.

The corners leaned.

The walls hummed.

The plaque outside the door flickered and relabelled itself twice before settling on something uncertain.

Ms Ledgerly stared at Alice in alarm.

“You cannot simply misbehave your way out of containment,” she said.

Alice picked up her basket.

“Watch me,” she replied.

Outside, Tartaria breathed again.

Not calmly.

But freely.

And far beyond it, a scholar paused mid-sentence, uncertain why his notes had suddenly become unreliable.

Alice stepped into the street, knowing two things with uncomfortable certainty.

She could still leave Tartaria.

But Tartaria might not let her go.

Chapter Seven

In Which Alice Attempts to Go Home, and Ballykillduff Does Not Entirely Cooperate

Leaving Tartaria turned out not to be the same thing as arriving.

Alice discovered this when she tried to walk in the direction of away.

She did not know precisely where that was, but she felt she ought to recognise it when she reached it. The trouble was that Tartaria had developed opinions about directions, and none of them were particularly helpful.

She set off down a street that seemed inclined toward departure.

After several minutes of walking, she found herself back where she had started.

This would not have been alarming had the street not greeted her.

“Back already?” it asked, mildly surprised.

“I did not mean to return,” Alice replied.

“Very few do,” said the street. “That is why we encourage it.”

Alice turned and walked the other way.

The buildings leaned.

Not dramatically. Just enough to suggest that they were listening carefully and might reposition themselves if necessary.

Old Nearly hurried to keep pace with her, his coat of LATER and NOT QUITE patches flapping with concern.

“You should not attempt this alone,” he said.

“I am not alone,” Alice replied. “You are here.”

Old Nearly sighed. “That is not what I meant.”

They reached a narrow lane that Alice felt certain had not existed during her arrival. It was lined with doors of different sizes, each bearing a small plaque.

NOT THIS WAY

CERTAINLY NOT THIS WAY

YOU HAVE TRIED THIS ALREADY

THIS WILL END BADLY

Alice paused before the last.

“That seems honest,” she said.

“Yes,” said Old Nearly. “We try to be fair at the end.”

She chose a door that said nothing at all.

The door opened.

The air on the other side was wrong.

Not hostile. Not dangerous. Simply incorrect, like a tune played one note too low.

Alice stepped through and found herself standing at the edge of Ballykillduff.

At least, she thought it was Ballykillduff.

The hedge was familiar. The lane curved in the proper place. The sky had the same thoughtful expression it always wore above the village.

And yet something was missing.

It took Alice a moment to realise what it was.

The village was not thinking.

The pauses were gone.

The gates opened immediately. The lane went exactly where it was told. Even the hedge looked cooperative.

Ballykillduff had become efficient.

Alice felt a chill.

She walked toward the centre of the village. People passed her with polite nods and purposeful steps. No one lingered. No one reconsidered.

Mrs Gaffney accepted her eggs without comment.

“You’re right on time,” Mrs Gaffney said approvingly.

“I am?” Alice replied.

“Yes,” said Mrs Gaffney. “Everything is these days.”

Alice left quickly.

The Old Creamery stood exactly where it should. The chimney did not smoke thoughtfully. It did not smoke at all.

Behind it, the grass stood upright.

Perfectly upright.

Alice swallowed.

She turned back toward Tartaria.

There was nothing there.

No crease. No sign. No suggestion of elsewhere.

Old Nearly stood beside her, looking very small.

“We have been leaking,” he said quietly.

Alice looked at him.

“Tartaria has been spilling into Ballykillduff,” he continued. “Stability follows absence.”

“And absence follows explanation,” Alice said.

Old Nearly nodded.

“If you leave Tartaria,” he said, “it will not remain empty. Something else will move in.”

Alice looked again at the grass.

It did not lean.

She did not like Ballykillduff like this.

“It feels wrong,” she said.

“Yes,” said Old Nearly. “That is how we know it is dangerous.”

Alice felt the basket tug.

She looked inside.

The eggs were still there. The folded card remained at the bottom.

MISREMEMBER ME

Alice closed the basket gently.

“I cannot leave Tartaria behind,” she said.

Old Nearly looked at her with relief and fear in equal measure.

“Then you must carry it properly,” he said.

“How?” Alice asked.

“Badly,” Old Nearly replied.

Alice smiled, slowly.

She turned back toward the village.

As she did, the hedge hesitated.

Only for a moment.

But it was enough.

Far away, a scholar frowned at his notes.

In Tartaria, a bell that did not exist rang almost loudly enough to be heard.

And in Ballykillduff, the grass behind the Old Creamery leaned, just a little, toward something that had decided it was not finished yet.

Chapter Eight

In Which Alice Begins to Misremember on Purpose, and Tartaria Answers Back

Alice decided to begin with something small.

This was sensible. Big mistakes attract attention, and attention, she had learned, was precisely what Tartaria could not afford.

So she began with a detail.

On her way through Ballykillduff the next morning, Alice mentioned—quite casually—that the Old Creamery had always had two chimneys, not one.

She did not insist on it. She did not argue. She simply said it in passing, as though correcting herself.

Mrs Gaffney nodded, distracted. “Of course it has,” she said. “Everyone knows that.”

Alice felt a curious sensation, like a thread being gently pulled somewhere behind her eyes.

When she passed the Old Creamery later, it had two chimneys.

Not newly built. Not obviously altered. They looked as though they had always been there and would be offended by any suggestion otherwise.

The grass behind the Creamery leaned.

A little more than before.

Alice stopped walking.

“That worked,” she said quietly.

Old Nearly appeared at her elbow, looking equal parts delighted and horrified.

“Yes,” he said. “And that is the trouble.”

Alice tried another misremembering that afternoon.

She told the postman that the lane near the church used to curve more sharply.

“I always hated that bend,” she said vaguely.

The postman frowned. “Yes. Awkward spot.”

By evening, the lane curved.

Not much. Just enough to be inconvenient.

Alice stood at the edge of it, her basket heavy on her arm, and felt the tug again.

This time, it was stronger.

Inside the basket, beneath the eggs, the folded card had changed.

It now read:

CARELESSLY

Alice did not like that word.

“I am being careful,” she said.

Old Nearly shook his head. “That is not what it means.”

By the third day, Ballykillduff was behaving oddly again.

Not cleverly. Not thoughtfully.

Differently.

People disagreed about small things. The pub sign changed its lettering twice. A fence leaned and then straightened itself again, uncertain.

This should have reassured Alice.

Instead, it frightened her.

Because Tartaria was no longer merely surviving.

It was responding.

That evening, as the mist thickened, Alice felt the familiar crease in the air.

But this time, it did not open where she expected.

It opened beside the river.

And Tartaria did not look calm.

The domes hummed loudly now, not administratively but urgently, like kettles that had been left too long.

Old Nearly met her at the edge, his coat patches fluttering.

“You must slow down,” he said. “You are being heard too clearly.”

“I am misremembering,” Alice replied. “That is what you said.”

“Yes,” Old Nearly said. “But you are doing it well.”

“That is bad?” Alice asked.

“Very,” said Old Nearly.

They walked through Tartaria as buildings flickered into and out of agreement.

A street ended where it had not ended before. A tower leaned permanently, exhausted by correction.

People argued openly now.

A woman insisted she had always lived on a street that no longer existed. A man complained that Tuesday had arrived twice.

This was not the gentle disorder Tartaria required.

This was strain.

They reached the great map.

It lay cracked.

Not broken. Cracked.

Lines overlapped. Rivers had begun to argue with themselves. The blank space at the centre pulsed more violently than before.

“That is not good,” Alice said.

“No,” said Old Nearly. “That is you.”

Alice stepped back.

“I am hurting it,” she said.

Old Nearly did not answer at once.

“You are teaching Tartaria that it can be changed deliberately,” he said at last. “That has never happened before.”

The map twitched.

A word appeared briefly along its edge, then erased itself.

Alice felt the basket grow heavier.

Inside, the card had changed again.

It now read:

REMEMBER ME WRONG,

BUT NOT TOO WELL

Alice closed her eyes.

She had thought misremembering was harmless.

She had been wrong.

And in Tartaria, being wrong was powerful.

That night, Alice dreamed of Ballykillduff folding into Tartaria, street by street, chimney by chimney, until neither place could quite recall which one had come first.

She woke with her heart racing.

Outside, the grass behind the Old Creamery leaned further than it ever had before.

And somewhere, deep within Tartaria, something that had never been meant to speak aloud began trying to form a sentence.

Chapter Nine

In Which Tartaria Recalls Alice Incorrectly, and This Proves Unsettling

Alice woke to find that her name was not behaving properly.

This was not immediately obvious. Names are subtle things and tend to wander if left unattended. It was only when Old Nearly greeted her with a polite hesitation that Alice began to suspect something was wrong.

“Good morning, Al—” he stopped. “Well. You.”

Alice frowned. “You know my name.”

“Yes,” said Old Nearly. “I do. I simply cannot reach it.”

“That is absurd,” Alice said.

“Quite,” Old Nearly replied. “Which is why it worries me.”

They walked together through Tartaria, which was in a state of restless correction. Buildings leaned, reconsidered, and leaned again. Streets that had behaved themselves yesterday now curved with unnecessary flourish.

And people were staring.

Not rudely. Not openly.

But as though Alice reminded them of something they had once misplaced and were uncertain whether they wanted back.

At a crossing, a woman paused and squinted at Alice.

“Excuse me,” she said. “Were you taller yesterday?”

“I do not think so,” Alice replied.

The woman nodded, unsatisfied. “That is what troubles me.”

They reached a small square where a plaque had appeared overnight.

It was mounted on a post that looked apologetic.

Alice leaned closer.

The plaque read:

THIS PLACE

WAS ONCE VISITED BY

SOMEONE

Alice felt a tightening in her chest.

“That is me,” she said.

Old Nearly peered at it. “Is it?”

“Yes,” Alice insisted. “I am the someone.”

Old Nearly scratched his chin. “You were. Yesterday.”

The plaque shimmered faintly.

A second line appeared beneath the first.

DETAILS UNCERTAIN

Alice stepped back.

The basket tugged sharply at her arm, heavier than before.

Inside, beneath the eggs, the folded card had changed yet again.

It now read:

DO NOT BECOME CONSISTENT

“I am not trying to,” Alice said aloud.

“That,” said Old Nearly quietly, “is no longer entirely up to you.”

They continued walking.

At the Academy of Necessary Forgetting, Miss Bramblehook failed to look at Alice directly.

“Attendance,” she said sharply, scanning the room. “One, two, three… discrepancy.”

Alice raised her hand. “I am here.”

Miss Bramblehook frowned at the empty space beside Alice’s desk.

“I am certain,” she said slowly, “that someone usually sits there.”

“I am sitting here,” Alice replied.

“Yes,” said Miss Bramblehook. “That is the inconsistency.”

The chalk squeaked violently.

Miss Bramblehook underlined something that was not written on the board.

“This is serious,” she muttered. “The city has begun correcting you.”

Alice felt suddenly cold.

They found the map cracked further.

The blank space at its centre no longer pulsed evenly.

Instead, it flickered.

Sometimes it showed a mark.

Sometimes it did not.

And when it did, the mark was not always in the same place.

“That is not right,” Alice said.

“No,” Old Nearly agreed. “You are being misfiled.”

A man hurried past clutching a stack of papers.

“Pardon me,” he said breathlessly. “Have you seen a girl who causes contradictions?”

Alice opened her mouth.

Then closed it again.

“I think she was here,” the man continued. “But I am no longer certain.”

He hurried on.

Alice swallowed.

“They are forgetting me,” she said.

Old Nearly shook his head. “Worse. They are remembering you incorrectly.”

“What happens if they finish?” Alice asked.

Old Nearly did not answer at once.

“When a place finishes remembering something,” he said slowly, “it stops needing it.”

Alice clutched the basket tighter.

That evening, Alice stood by the river where Tartaria first answered her.

The water did not reflect her properly.

Her outline wavered. Sometimes she appeared younger. Sometimes older. Sometimes not quite present at all.

She spoke quietly, not to the river, but to the city.

“You cannot have me,” she said.

The domes hummed, uncertain.

A ripple passed through Tartaria.

Somewhere, a bell that did not exist rang once, badly.

And Alice realised, with a clarity that frightened her more than pursuit or containment ever had, that the danger was no longer that Tartaria would collapse.

The danger was that Tartaria might decide she was a mistake.

Chapter Ten

In Which Alice Attempts to Be Certain, and Discovers That This Is a Mistake

Alice decided that if she was being misremembered, she would at least try to be remembered on purpose.

This seemed reasonable at the time.

The trouble with reason, she was learning, was that it behaved very badly in Tartaria.

She chose a morning when the domes were humming quietly, not urgently, and the streets were behaving themselves just enough to be suspicious. She stood in the centre of a small square that had agreed, for the moment, to remain a square.

“I am Alice,” she said aloud.

The words felt solid as she spoke them. This pleased her.

“I am Alice,” she repeated. “I am from Ballykillduff. I arrived here by accident, and I am still myself.”

The air listened.

For a moment, nothing happened.

Then the square tightened.

Not visibly. Not dramatically. It simply became more exact. Corners sharpened. Lines straightened. A lamppost ceased flickering and decided very firmly what it was.

Old Nearly appeared beside her, looking alarmed.

“Stop that,” he said urgently.

“I am only saying who I am,” Alice replied.

“Yes,” said Old Nearly. “That is precisely the problem.”

The city responded.

Not with resistance. With agreement.

Plaques appeared.

One on the lamppost read:

ALICE

(VERIFIED)

A building nearby acquired a small brass plate.

ALICE PASSED HERE

ONCE

Alice felt a strange heaviness settle around her, as though she were being gently pressed into place.

“That is not right,” she said.

“No,” said Old Nearly. “You are being fixed.”

The map arrived without warning.

It did not stand upright this time. It lay flat across the square, unfolding itself eagerly, lines snapping into place with satisfaction.

At its centre, the blank space vanished.

In its place appeared a neat, confident mark.

Labelled.

Alice.

“There,” said a voice behind her. “Much better.”

Dr Percival Index stepped into the square, looking pleased.

“Clarity at last,” he said. “You have made yourself wonderfully easy to place.”

Alice turned slowly.

“I was only trying to stop myself from disappearing,” she said.

“And you have,” Dr Index replied. “By becoming precise.”

“That is not safety,” Old Nearly said sharply. “That is preparation.”

The square grew quieter.

Too quiet.

People gathered at its edges, watching with polite interest. They did not argue. They did not hesitate.

This frightened Alice more than pursuit ever had.

The map gleamed.

Rivers obeyed themselves. Streets straightened. The city held its breath.

“You see,” Dr Index continued, “uncertainty causes distress. Explanation brings order.”

“And what happens to Tartaria?” Alice asked.

Dr Index smiled. “It will be resolved.”

Alice looked at the map.

For the first time, she understood what that meant.

Resolved was not saved.

Resolved was finished.

The basket tugged violently at her arm.

Alice looked inside.

The eggs were gone.

In their place lay a single sheet of paper, heavier than it ought to be.

It read:

YOU ARE TOO CLEAR

Alice closed her eyes.

She had tried misremembering.

She had tried resisting.

Now she had tried certainty.

And all of it had made things worse.

She took a breath and did something she had not done yet.

She contradicted herself.

“I am Alice,” she said, “but not always.”

The plaque on the lamppost flickered.

“I am from Ballykillduff,” she continued, “except when I am not.”

The map trembled.

“I arrived by accident,” she said, “on purpose.”

Lines blurred. Labels smudged.

The square wavered.

Dr Index frowned. “You are undermining the framework.”

“Yes,” said Alice. “That is the idea.”

The city exhaled.

Corners softened. The plaques lost confidence. The map’s neat mark smeared, then faded.

Not gone.

But uncertain again.

Old Nearly let out a breath he had been holding since before Alice arrived.

“You cannot anchor yourself,” he said gently. “You must drift correctly.”

Alice nodded, understanding at last.

Certainty was a trap.

For people.

For places.

For stories.

The domes resumed their hum, thoughtful once more.

Dr Index stepped back, troubled.

“This is not sustainable,” he said.

“No,” Alice replied. “It is survivable.”

That evening, Alice stood again by the river.

Her reflection was not perfect.

But it was hers.

Mostly.

She smiled faintly.

She was not finished.

And neither was Tartaria.

To be continued.