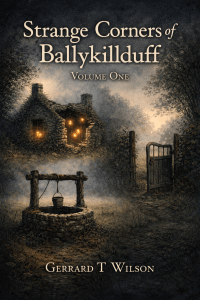

Strange Corners of Ballykillduff – Volume One

Strange Corners of Ballykillduff

Volume One

Stories from the quiet edges of the village

where memory lingers a little longer

and ordinary places sometimes forget to remain ordinary.

Introduction

Ballykillduff is not a large village, but like all villages, it has corners that do not appear on maps.

These are places people pass without stopping, places where stories settle like dust and remain undisturbed for years. Nothing remarkable ever seems to happen there — until someone remembers that something once did.

The tales in this collection belong to those places.

They are not ghost stories, exactly.

Nor are they legends.

They are simply things Ballykillduff remembers.

The Lantern-Keepers of Currans Lane

At the very end of Currans Lane — beyond the hedgerow that leaned across the road as though listening for secrets — stood the remains of a house nobody in Ballykillduff could quite remember being lived in.

The roof had long since fallen away. Ivy stitched the stone walls together with green thread, and a narrow chimney rose from the ruin like something trying to remember the sky.

People did not avoid the place.

They simply never found a reason to visit.

Except, now and again, to take photographs.

The first photograph was taken by accident.

Seamus Kelleher had bought a second-hand camera at the Carlow market and gone walking along Currans Lane to test it. Seeing the ruin at the end of the lane, he lifted the camera and took a single picture, thinking the old stone walls might look interesting in black and white.

When the photograph was developed, he noticed something peculiar.

Inside the dark window of the broken house floated three small golden globes of light.

They looked like tiny lanterns.

Seamus assumed it was a fault in the film.

Until he returned the next day and took another photograph.

This time there were four.

Word travels in Ballykillduff the way smoke travels — slowly, but everywhere at once.

Within a week, half the village had taken photographs of the house.

Every image showed the same thing:

golden globes floating inside the ruin.

Never in the same place.

Never in the same number.

Always glowing softly, like candlelight seen through mist.

Yet when anyone stood before the house with their own eyes, there was nothing inside but shadow and weeds.

Old Mrs Fitzgerald, who remembered things other people had forgotten, was the first to speak of the lantern-keepers.

“That house,” she said one evening in the Giddy Goat, “belonged to the O’Dalaigh family long ago. They kept lanterns in every window.”

“For what?” someone asked.

“For the lost,” she replied simply.

Years ago — no one could say exactly when — travellers often lost their way on the bog roads beyond Currans Lane. Winter fog would fall thick and sudden, swallowing fields and fences alike.

The O’Dalaigh family believed that light could guide the wandering safely home.

So each night, they lit lanterns in their windows.

Not for themselves.

For anyone who might be searching for a road.

People said the house glowed like a small constellation at the end of the lane.

And sometimes, figures appeared from the fog and knocked upon their door.

The night the house burned, the fog was heavier than ever before.

Some claimed they saw lights moving across the fields long after the roof had fallen in.

Others said the O’Dalaigh lanterns never went out at all.

They simply changed their purpose.

The photographs continued for years.

Tourists sometimes stopped to take pictures, not knowing the story. When they checked their cameras, the golden globes were always there, floating patiently inside the ruin.

Never fewer than three.

Never brighter than candlelight.

Always waiting.

One winter evening, when fog crept low across the fields beyond Currans Lane, something unusual happened.

A car from outside the village took a wrong turn on the narrow road and stalled near the bog.

The driver later swore he saw small golden lights drifting ahead of him across the field, moving slowly like someone carrying lanterns.

He followed them.

They led him back to the lane.

When he reached the road again, the lights vanished.

Behind him, barely visible through the mist, the ruin of the house stood quietly at the end of Currans Lane.

Even now, people in Ballykillduff sometimes take photographs of the place.

The golden globes always appear.

Still guiding.

Still remembering.

Still keeping watch.

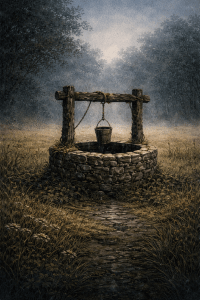

The Well That Did Not Give Back

There is a field outside Ballykillduff that farmers prefer not to use.

It is not poor land.

The grass grows well enough there, and the soil is dark and good.

But in the middle of the field stands an old stone well, and the cattle never graze within ten steps of it.

Even in summer.

Animals, it seems, remember things people forget.

The well is older than the village, or so it is said.

It is lined with heavy stones worn smooth by time, and a ring of moss grows around its edge like a collar that cannot be removed. The water inside looks black, even on the brightest day.

No one knows how deep it goes.

Several have tried to measure it.

None succeeded.

Long ago, the well was considered useful.

Travellers watered their horses there, and villagers drew water in dry weather when the stream ran thin. Children were warned not to lean too far over its edge, but that was ordinary caution, not fear.

The well behaved like any other well.

Until the summer it did not give something back.

A boy named Liam Brogan dropped his father’s brass pocket watch into the water while trying to see his reflection.

The watch slipped from his fingers, flashed once in the sunlight, and vanished below.

Liam ran home in tears.

His father lowered a bucket into the well again and again, certain it could be retrieved.

Each time the bucket returned empty.

After an hour, he gave up.

“It’s only a watch,” he said.

But that evening, he stood in the doorway looking toward the field longer than usual.

The next morning, the watch lay on the kitchen table.

Wet.

Cold.

Ticking.

No one spoke of it.

After that, people noticed small things.

A dropped coin returned days later on a windowsill.

A lost button appeared on a doorstep.

A missing thimble was found beside a bed.

Always damp.

Always cold.

Always slightly darker than before.

Then came the autumn of the sheep.

One ewe wandered too near the well and fell in during heavy rain.

Three days later, the ewe was discovered standing at the far end of the field.

Alive.

But wrong.

After that, the well was left alone.

One evening, boys dared one another to throw a stone into it.

They waited for the splash.

Instead, they heard a second stone strike the grass behind them.

They ran.

Even now, farmers say the well grows colder as winter approaches.

The well gives things back.

Eventually.

But never quite the same.

Great — here’s the remainder of the storybook edition, continuing from Story Three onward.

The Gate That Closed After You

There is a narrow path behind the old post office in Ballykillduff that leads between two hedges and into a field no longer used.

At the entrance to the path stands a small iron gate.

It is painted green, though the paint has peeled in places where time has rubbed against it. The hinges do not squeak, and the latch is simple enough for a child to lift.

Nothing about the gate appears unusual.

Except that it closes after you.

People noticed it slowly.

At first, they assumed the wind was responsible. A gate on a light latch will swing shut easily enough, and Ballykillduff has never been short of wind.

But the gate closed on still days.

It closed on warm afternoons.

It closed in the quiet of evening when the air did not move at all.

Always gently.

Never with a slam.

Years ago, the path was used often.

It led to a field where children played football, where dogs chased sticks, and where older villagers walked in the evenings when walking felt easier than sitting still.

The gate was opened many times each day.

And always, after someone passed through, it closed.

One summer afternoon, Jimmy Doyle decided to test it.

He opened the gate and held it wide with his hand.

He waited.

Nothing happened.

Then he stepped through the opening and let go.

Behind him, without sound or hurry, the gate swung shut.

Jimmy never spoke of it again.

Old Mrs Fitzgerald explained it once.

“That gate remembers when the field was busy,” she said. “It was opened too often to forget how.”

Time passed.

The field was no longer used.

The path grew narrower.

Grass rose between the stones.

Fewer people walked there.

But the gate continued to close.

One winter morning after heavy frost, footprints were found on the path.

They led from the village to the gate.

None came back.

The gate was closed.

Even now, if you walk behind the old post office and follow the narrow path between the hedges, you will find the small green gate standing exactly where it always has.

You may open it.

You may walk through.

But you should not be surprised when, behind you, the gate closes gently once more.

As though it remembers how.

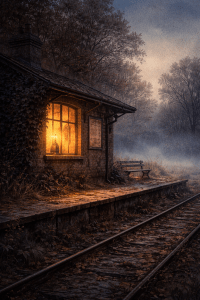

The Light in the Empty Station

There was once a railway station a short walk beyond Ballykillduff, though few now remember exactly where it stood.

The line itself had been lifted long ago. The sleepers were gone, the rails melted into other shapes, and the platform stones were slowly being taken back by grass and moss.

No trains had stopped there for over fifty years.

Still, sometimes, the light was on.

A farmer crossing the fields at dusk saw the faint yellow glow through the waiting-room window and assumed someone from the railway had come to inspect the building.

But the next day, the station was empty.

The dust lay undisturbed.

The door remained locked.

No footprints marked the ground outside.

The light appeared again the following week.

Then again the month after.

Always at evening.

Always in the waiting room.

Always steady, like an oil lamp placed carefully on a table.

Long ago, the station had been small but busy.

Children once pressed their faces to the glass to watch for trains. Farmers waited there on market mornings, boots muddy and hats pulled low. Letters and parcels arrived with the rhythm of steam and whistles.

And each evening, after the last train had gone, the stationmaster lit a lamp in the waiting room before locking up.

He said travellers should never arrive at a dark station.

The railway closed in autumn.

The final train passed Ballykillduff under a sky the colour of smoke.

That evening, the stationmaster locked the building for the last time.

And, as always, he lit the waiting-room lamp.

Years passed.

But sometimes, at evening, the light returned.

Once, a man walking home across the fields saw the glow and pressed his face to the window.

Inside stood a wooden bench, a timetable, and a small oil lamp burning quietly on a table.

The flame did not flicker.

In the morning, nothing remained but dust.

Now the building stands quietly where it always has.

And on certain evenings — not often, but not never — a warm yellow light can be seen through the waiting-room window.

As though the stationmaster still believes someone might arrive.

The Last Lamp in Ballykillduff

There was once a time when every road in Ballykillduff was lit by lamps.

Not electric lights, but glass and brass lamps lit by hand each evening.

A lamplighter named Pat Keane walked the village with a ladder on his shoulder and a small tin of oil at his side.

Children sometimes followed him as the lamps bloomed one by one.

Electric lights came later.

One by one, the old lamps were removed.

At last, only one remained.

It stood beside the village green.

Pat lit it every night until the day he did not.

After that, the lamp stood dark.

For a while.

The first time it lit again, no one saw it happen.

A woman returning home late noticed the small golden glow beside the green.

In the morning, it was cold again.

The lamp began to glow from time to time.

On foggy evenings.

On quiet Sundays.

On nights when the village seemed to remember itself.

One winter evening, the lamp shone brighter than anyone remembered.

By morning, footprints crossed the green from the old shed to the lamp and back again.

Only one set.

Inside the shed stood a wooden ladder and a small oil tin.

Waiting.

Even now, sometimes, the last lamp glows.

Just enough to show the road home.

Author’s Note

Every village has places that do not entirely belong to the present.

In Ballykillduff, such places are not feared. They are simply accepted — like old trees, quiet roads, and stories that have been told too often to disappear.

These tales are about memory more than mystery — about light left burning, gates remembering hands that opened them, and small corners of the world that continue doing what they were once meant to do.

If Ballykillduff has strange corners, it is only because every village does.

And sometimes, noticing is enough to keep them alive.

— Gerrard T Wilson