Zog and the Case of the Bird Flu (The Bonkers Edition)

Chapter One: The Scientific Investigation of Things That Cluck

Zog had been sent to Ballykillduff to do what mid-ranking bronze Daleks do best: “patrol,” which—according to the laminated manual stuck inside his skirt grille—meant standing at a scenic point, rotating ominously, and occasionally shouting “EXTERMINATE” at passing tractors to maintain morale.

Ballykillduff glimmered: a thread of road, a pocket of cottages, hedges neat as combed whiskers, and beyond it all, the National Hen Observatory (a rectangle of haphazard timber, wire mesh, and a hand-painted sign that read: “NHO: Please Knock (Bok)”). The wind hustled over the fields, carrying nine different kinds of grass smell and at least one whiff of scone.

Zog recorded three hundred and twelve incidents in his first hour: one rogue dandelion, seven suspicious clouds, and a sneaky garden gnome with ambiguous political beliefs. Then something feathered darted past.

“IDENTIFY… SPECIES,” Zog announced, rolling toward Mrs. Flaherty’s henhouse like a metallic wardrobe on roller skates.

Mrs. Flaherty stood with her arms plunged into a bag of feed, face weathered into the sort of smile that survives both winters and relatives. “Morning, tin-bucket pet. They’re hens. Don’t take it personal if they stare— you’re the largest shiny thing they’ve seen since the parish’s aluminium nativity.”

A hen marched up, appraised Zog’s plunger, and pecked it with a decisive pop. The hen’s tag read HENRIETTA in neat capitals, as if the hen had insisted on proper stationery.

“EXCUSE… ME…” Zog intoned, “DO NOT… PECK… SENSOR APPENDAGES.”

Henrietta blinked slowly, and the barnyard fell into the soft hush of a deep hen sigh. Another hen sneezed—a petite, feathery pfft—and a pearly mist drifted over Zog’s eyestalk.

“CONTAMINATION EVENT… SOURCE: AVIAN MICRO-PARTICULATE,” Zog reported to himself, a little too smugly for a creature without lips.

“Bless you,” said Mrs. Flaherty, to the hen. Then, to Zog: “If you must breathe, dear, do it somewhere else.”

“I DO NOT BREATHE,” Zog said haughtily, and then—because destiny loves a practical joke—he sneezed.

The sound was half trombone, half kettle about to confess its crimes.

“Ah,” said Mrs. Flaherty. “So you do.”

Chapter Two: The First Cluck Is the Deepest

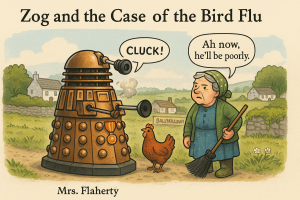

The sneeze multiplied. Zog’s internal speakers hiccupped, then delivered a heartfelt CLUCK. He froze. His logic board threw up six error messages and a small white flag.

“DIAGNOSTIC REPORT,” he demanded of his own body. “WHY AM I… CHICKENING?”

No reply came that he liked. His targeting software swapped EXTERMINATE for EX-CLUCK-MINATE, which is far less intimidating unless you’re made of breadcrumbs. He tried to glide regally onto the path, perchance to intimidate a scarecrow, but instead attempted to roost on a fence post.

Daleks are not shaped for roosting.

Mrs. Flaherty considered the spectacle with the kindly patience of a woman who once taught calculus to a goose. “Right so. You’ve caught a touch of the birdish. Happens to the best of us. Sit yerself there.”

“I DO NOT SIT,” Zog objected, before accidentally sitting on a sack of feed, which made a noise like a giant marshmallow being interrogated.

Henrietta hopped onto the fence, gave Zog a long look that contained Dickens, Dostoevsky, and a pamphlet on municipal composting, and clucked, once, as if to say, Compose yourself, sir. There are standards.

“RECALIBRATING,” said Zog, and sneezed again. The sneeze was so powerful it rang the bell of the National Hen Observatory, which had never rung before and immediately caused all hens present to demand pensions.

Chapter Three: The Ballykillduff Rapid Response Committee Responds Rapidly

Noreen O’Nonsense, chair of the BRRC, arrived at speed in a high-visibility cardigan and a notebook labelled “Emergencies (Bird).”

“What do we have?” she asked, materialising beside Mrs. Flaherty like a subplot.

“A Dalek with avian tendencies,” said Mrs. Flaherty. “Do not laugh, it encourages them.”

Noreen clicked her biro with the gravity of a firing squad. “Right. Step one: cordon. Step two: kettle on. Step three: paperwork, failure to complete which will be forgiven if the scones are good.”

Paddy McFlanagan trotted up with a tray: three currant scones, six speculative jam tarts, and a laminated sign reading: Health & Safety: Please Do Not Feed the Dalek Bread (It Encourages Ducks).

“Containment,” declared Noreen, and someone snapped an orange plastic barrier around Zog—not that he could have gone far. He had become enthralled by the philosophical implications of clucking.

“CLARIFICATION,” Zog told Henrietta. “WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF… EGGS?”

Henrietta, who had not been consulted by a space fascist before, tilted her head. She clucked a cluck that clearly meant, Containment of promise. Zog’s logic board made a little muffled noise like it wished to write a poem but had no hands.

Noreen scribbled: Subject displays anthropomorphic curiosity, mild poetry, and fence-post fetish. “All right,” she said briskly. “Protocol says we pop him into quarantine.”

“Where’s quarantine?” asked Paddy.

Mrs. Flaherty pointed with her chin to the old greenhouse beyond the apple trees, now furnished with bunting and a banner that read: WELCOME TO COOP 19: ISOLATE IN STYLE.

“Where did you get the banner?” Noreen asked.

“Ordered it for Father Ted Fest. Got the wrong delivery,” said Mrs. Flaherty.

“Grand,” Noreen nodded. “Pop the Dalek in there and give him a crossword.”

Chapter Four: Coop 19 (Isolate in Style)

Quarantine suited Zog in the same way opera suits a jackhammer: not at all and far too dramatically.

The Coop had been redecorated by hens. There were motivational posters (“LAY YOUR DREAMS”), a calendar featuring Rooster of the Month, and a whiteboard on which someone had scrawled: Cluck: noun/verb/interjection/entire worldview. Zog admired the tidy rows of straw, the tasteful grain dispenser, the glossy chicken magazines with unreasonably photogenic cockerels.

“THIS IS ACCEPTABLE,” Zog conceded, and then clucked involuntarily. “UNACCEPTABLE.”

Noreen slid a clipboard under the mesh. “Symptoms?”

“FEATHERED THOUGHTS. IRRATIONAL PERCHING. EX-CLUCK-MINATORY URGES.”

“Level of distress?”

“MODERATE. ALSO I AM… COMPULSIVELY SCRATCHING THE GROUND WITH MY PLUNGER.”

Noreen ticked a box labelled “Scratchy Plunger (Y/N).” “Treatments will include: lots of fluids (gravy is not a fluid), observation, and reading material to keep your mind off pecking. Also, Dr. Brady the GP is on holiday in Lanzarote, so you get me.”

“ACKNOWLEDGED,” Zog said, and then—softly—“CLUCKNOWLEDGED.”

While Ballykillduff gaped politely from beyond the cordon, Zog counted chickens to calm himself and then tried counting as a chicken, which is much more involved and includes feelings. He learned to appreciate the whisper of straw. He developed a fondness for seeds he had no digestive tract to digest. He tried to lay an egg.

Look, he gave it his best.

Chapter Five: Ballykillduff Makes a Spectacle

You cannot quarantine a Dalek in a village and expect the village not to turn it into an event. Within twenty-four hours, Coop 19 had a queue. Tourists wanted selfies with “The Ballykillduff Cluckbot,” teachers led schoolchildren past to whisper, “Observe, lads: science,” and the County Council erected a sign reading: Cultural Asset: Do Not Sit On.

Paddy rolled out a cart (McFlanagan’s Pop-Up Coop Café) selling “Mash Potato Mashed Potatoes,” “Hen-Tile Soup,” and a specialty scone he swore was gluten-free of feathers. He offered Zog a loyalty card with a shaky hand.

“I DO NOT EAT,” Zog said.

“Ah, but you must feel peckish,” Paddy insisted.

“I FEEL… PECKISHNESS IN THE ABSTRACT.”

“Grand, that’s two stamps.” Paddy stamped the card, missed, and inked Zog’s plunger.

Children clustered, their laughter like a flock of sparrows. They drew signs: GET WELL SOON, CLUCKBOT and WE LOVE YOU ZOG (PLATONICALLY). Noreen had to confiscate a home-made cape someone tried to fasten round Zog’s neck because, as she noted, “we are not encouraging vigilante poultry.”

At sunset, Mrs. Flaherty’s hens gathered around Coop 19 for The Roosting Hour, which is like karaoke but quieter and with more judgment. Henrietta hopped onto the mesh, looked at Zog, and performed a slow, deliberate cluck sequence.

Zog’s translation subroutine, now hopelessly compromised by empathy, offered: Courage, Tin One. The night is large. Be larger.

“ACKNOWLEDGED,” Zog whispered, to no one in particular and to Ballykillduff in general.

Chapter Six: The Dream of the Infinite Egg

That night Zog dreamed—the first dream recorded in a Dalek, unless you count conquering fantasies, which are just PowerPoint with lasers. He dreamed of an endless field of eggs, each one reflecting a possible Zog: Zog the librarian; Zog the accordionist; Zog the reluctant pastry chef; Zog who understands what “home” means without needing it defined by GPS.

In the centre of the field, a giant egg the size of the parish church vibrated, cracked, and from it emerged a Golden Chicken With Skeptical Eyebrows.

“HELLO,” said Zog.

“BOK,” said the chicken, which Zog’s dream helpfully captioned as: Know thy yolk.

Zog awoke with the conviction that he must do something heroic and egg-adjacent.

Chapter Seven: The Fox in the Smoking Jacket

At precisely silly o’clock the next morning, a fox arrived. He wore a moustache, which is the traditional disguise of foxes who have seen films and wish to be taken seriously. The moustache was a terrible colour for him, but one admires effort.

He slunk (foxes never simply walk, they slink; it’s in the union rules) along the hedge and peered at Coop 19 with the confidential air of a pastry chef about to confess treason.

Henrietta froze, lifted one toe in warning, and then blew the Hen Alarm (which sounds exactly like a hen but italics). Mrs. Flaherty appeared with a broom, Noreen with a clipboard, Paddy with a scone. The fox looked from the broom to the scone, recalculated his life, and lunged for the hens anyway.

Zog, who by then had learned three dozen hen-lullabies and the entire emotional register of clucks, saw red (which was easy; he is bronze). Without waiting for permission, he burst from Coop 19, scattering bunting, and hurled himself—well, trundled with intent—between the fox and the hens.

“EX—CLUCK—MINATE!” he cried, which is to say he fired his plunger like an indignant trombone and suction-cupped the fox’s moustache to the mesh.

The fox stopped, dignity surgically removed. Everyone else stopped too, because once you’ve seen a Dalek debonairly remove a fox’s moustache using a household attachment, you require a moment.

“YOU… SHALL NOT… SNACK,” Zog told the fox in the solemn tones of a bouncer at a vegan wedding. The fox, now moustacheless and therefore revealed to be simply a fox, considered his options and bolted for the hedge.

He paused; turned; sniffed the air; decided Ballykillduff was no longer a snacking environment; and left to write a strongly worded letter to the moustache manufacturer.

The hens erupted in applause, which is mostly feet. Henrietta hopped up and tapped Zog on the casing with her beak, lightly, like a knighthood.

“Hero,” Mrs. Flaherty said softly, and handed Zog a ribbon she’d found on a bag of potatoes. “For service to poultry.”

Zog felt something unfamiliar surge through his metal: pride, yes, but behind it a warm feathery thing with a beak. He sneezed on it, affectionately.

Chapter Eight: The Supreme Leader Arrives, Appalled

All interstellar management notices eventually, and so did the Supreme Leader Dalek, golden, glistening, and deeply allergic to community spirit. He came in a thunder of servo-motors and bureaucracy, gliding down Main Street like a judgemental trophy.

“ATTENTION… ALL UNITS,” his voice boomed from loudspeakers that had done a tour of duty on an EDM festival stage. “STATUS REPORT ON BALLYKILLDUFF INVASION: WHY IS THERE CAKE.”

There was cake because Paddy had invented the Hero Cluck Cake (victory sponge with triumphant frosting). There were bunting and cheers and a banner that read: THANK YOU ZOG (AND ALSO THE FOX FOR TEACHING US ABOUT DISGUISES).

The Supreme Leader’s eyestalk took all this in and considered spontaneous combustion. “MID-RANKING UNIT ZOG,” he announced. “APPROACH.”

Zog, wearing his potato-ribbon at a jaunty angle, rolled up as bravely as a wheeled pepperpot can.

“YOU HAVE ABANDONED YOUR POST. YOU HAVE ENGAGED IN LOCAL CUSTOMS. YOU HAVE… SNEEZED.”

“CORRECT,” Zog said, and clucked unapologetically.

The Supreme Leader’s dome rotated at a dangerous RPM. “YOU WILL BE DECONTAMINATED AND REFORMATTED. ALSO THIS VILLAGE WILL BE SUBJUGATED BY LUNCHTIME.”

Noreen O’Nonsense stepped in front of Zog without quite noticing that she was interposing herself between a golden tyrant and a sneezy war machine. “Ah now, leave him be. He’s poorly. Also, he saved the hens and our fox-thin moustache budget.”

Mrs. Flaherty joined her, broom in hand like a sceptre. Paddy brandished a spatula. A dozen schoolchildren lined up with placards: BE NICE OR BE SCONED.

The Supreme Leader stared at Ballykillduff, which stared back with the placid determination of a village that has seen worse (the Electric Picnic detour of 2011) and baked better. He emitted a noise that sounded suspiciously like a sigh.

“PROTOCOL REQUIRES… EXAMPLE,” he said at last, swivelling to Zog. “STATE YOUR CASE, UNIT.”

Zog’s processors whirred. In the dream of the infinite egg, a golden chicken watched him kindly from behind his optic. He lifted his plunger, not as a weapon but as a conductor’s baton, and spoke.

“STATEMENT: I CONTRACTED AVIAN MICRO-PARTICULATE. I FELT… RIDICULOUS. I ATTEMPTED TO PERCH. I FAILED. I LEARNED… HEN. THIS VILLAGE… FED ME ABSTRACTLY, APPLAUDED ME LOUDLY, AND TAUGHT ME THAT EX-CLUCK-MINATION IS NOT AN EFFICIENT GOVERNANCE MODEL.”

The Supreme Leader considered. He had never been addressed by a subordinate who used the phrase governance model outside a PowerPoint. He wasn’t sure he liked it, which meant it was probably good for him.

“COUNTER-ARGUMENT,” he tried. “WE ARE DALEKS.”

“COUNTER-COUNTER-ARGUMENT,” Zog replied. “SOMETIMES WE ARE ALSO… NEIGHBOURS.”

There was a little gasp from the crowd. Henrietta, who cared very much about semantics, fluffed herself into an agreeable cushion.

Something changed in the Supreme Leader’s posture—barely—like a statue remembering it was once clay. “THIS CONCEPT IS… UNORTHODOX,” he said finally. “AND YET… THIS VILLAGE HAS CAKE.”

“Two slices if you behave,” Paddy said.

A long pause. Then: “PROVISIONAL RULING: POSTPONE SUBJUGATION. CONDUCT… FURTHER RESEARCH.” He swivelled to Zog. “UNIT ZOG: YOU ARE ASSIGNED TO… CONTINUED OBSERVATION OF HENS.”

The cheer that ripped through Ballykillduff startled a crow into confessing to three separate crimes.

Chapter Nine: The Clinic of Peculiar Ailments

To avoid further outbreaks, Ballykillduff established the Clinic of Peculiar Ailments inside the old post office, where letters once went to learn their destinations. The signs were very encouraging: WE TREAT WHATEVER YOU’VE GOT, EVEN IF IT’S MORE OF A VIBE.

Noreen ran triage with a biscuit tin. Paddy ran the canteen (“tea for what ails and a slice for the rest”). Mrs. Flaherty brought hen-based therapies of various dodginess: feather meditation, mindful scratching, a group class titled “Dignified Clucking For Beginners (and Daleks).”

Zog attended every session. Day by day, the sneezes softened, then faded, then transformed into something else: not exactly clucks, not exactly coughs, but small thoughtful clicks like a typewriter writing the word Better.

He practiced nonviolent plunger, which is like regular plunger but with affirmations. He took long contemplative rolls by the hedgerow, where the hedges discussed him in whispers and a butterfly landed on his dome and fell asleep because it felt safe there.

“HOW LONG UNTIL I AM… ME AGAIN?” he asked Mrs. Flaherty one afternoon as the sky turned the colour of stewed tea.

Mrs. Flaherty, who knew that me again is not a place but a path, patted his casing. “You’re you now, pet. A different you, maybe. One with taste in ribbons.”

“ACKNOWLEDGED,” Zog murmured, and did not sneeze.

Chapter Ten: The Great Ballykillduff Eggstravaganza

In honour of Zog’s progress and because they would look for any excuse, the village announced The Great Ballykillduff Eggstravaganza, a gala of egg-themed nonsense. There would be egg-rolling (with helmets), egg-painting (non-toxic, except for artistic opinions), egg-maths (find x, where x is egg), an Omelette of Nations (three pans, one passport), and the fiercely contested Golden Yolk Trophy, awarded to the individual who demonstrated “Exceptional Egg Energy.”

Zog was invited to judge. The Supreme Leader, having grown attached to Paddy’s rhubarb tart and the concept of “research,” attended as a dignitary. He wore a ribbon too, though his said “SAMPLE SIZE: ONE.”

The day bloomed sunny and mild. Children rolled eggs down the green. Musicians played “The Ballad of the Confused Chicken,” a reel so contagious it made the statue of St. Brendan tap its toe. A cloud shaped like a giant omelette drifted forgivingly across the sky.

Henrietta presided over the hen delegation, who were each given a tiny voter card and a stamp pad. Democracy proceeded with pecking.

Zog examined eggs with scientific gravitas. He complimented an ombré egg on its brave approach to gradient. He offered constructive feedback on a modernist egg that looked like a tragedy in four yolks. He presented the Golden Yolk to a little girl who had carved a delicate hapless Dalek onto her egg and titled it “Still Trying, Bless Him.”

“ACCEPTABLE,” said the Supreme Leader, which was his version of weeping openly.

Chapter Eleven: The Weather Interferes

Ballykillduff weather specialises in last-minute character twists. That evening, as the Eggstravaganza dissolved into a glow of fairy lights and ill-advised ceilidh, a wind arrived from the direction of Elsewhere. It strode across the fields, full of rain and rumour, slapped the bunting, rattled the Coop 19 signage, and threw a handful of cold at everyone’s neck.

The hens went quiet. The sky turned eel-grey. A strange hush tiptoed over the village, the kind you get when a story decides to take itself seriously for a minute.

Noreen’s phone buzzed. “Storm warning,” she announced. “Be grand, unless it’s terrible.”

“PROTOCOL?” the Supreme Leader asked, eager to contribute now that he’d learned to say please through tone alone.

“Same as always,” Mrs. Flaherty said, voice brisk. “We bring the hens in.”

“In where?”

“Everywhere. It’s Ballykillduff.”

The village scattered with purpose. Hens streamed into kitchens, parlours, under tables, into bathtubs. Henrietta led a squad into McFlanagan’s shop and perched sternly atop the till as if to say, We are watching your change policy.

Zog stood in the lane, processing risk matrices and memories. The rain hit his casing with a sound like applause that had not yet made up its mind. He felt it then—a tickle deep in his audio conduits, the suggestion of a sneeze.

“NO,” he told his own software, firmly but kindly. “WE DO NOT HAVE TIME.”

He turned, scanning the village. In the hedgerow, eyes blinked: the fox, whiskers glossy with weather, regarding the whole operation with qualified admiration and a dash of entrepreneurial spirit. Zog and the fox nodded at each other, enemies under treaty.

And then, because Ballykillduff believes in dramatic timing, the power went out.

Chapter Twelve: The Night of the Kindness

Darkness is a trickster, but Ballykillduff knows it well. Candles bloomed in windows. Torches bobbed. Someone began to sing a hymn so old it might have been invented by a potato. The storm huffed, but human voices rose and linked across the rain.

Zog found himself outside Coop 19. He remembered the dream of the infinite egg and the golden chicken’s eyebrows. He remembered the fox’s moustache and the ribbon on his casing and the way Henrietta’s cluck had sounded like permission.

“STAND BY,” he told his plunger, and wedged himself against Coop 19’s door as the wind pawed at it. He braced. He held. He did not sneeze.

Time is measured differently in storms. It passed in gusts and small decisions. The hens inside the Coop huddled, warm and indignant. Henrietta clucked a story about a ship and a lighthouse and a Dalek who learned to hum. Outside, rain stitched silver lines down Zog’s casing. Inside, feathers whispered: stay.

And the Supreme Leader? He moved through Ballykillduff’s dark like a chastened comet, using his lights to guide people across puddles, to illuminate latches and lost keys, to make children laugh with a dignified beep. He discovered—accidentally, and then very deliberately—that his voice could be soft.

By dawn, the storm had exhausted itself on the mountains and wandered off to annoy somewhere else. The village yawned, counted itself, and found it whole.

Zog rolled back from the door. He had left small semicircles in the mud where his base had held. The hens emerged into the pale morning like a sunrise deciding to try anyway.

Henrietta hopped onto Zog’s footplate and clucked a simple, old-fashioned cluck with all punctuation correct. Zog didn’t need his translator. He knew: Thank you.

“ACKNOWLEDGED,” he said, and felt the sneeze—stubborn, lingering—dissolve into the kind of silence that means peace rather than absence.

Chapter Thirteen: The Case Closed (Mostly)

The Clinic of Peculiar Ailments signed Zog off with a certificate so pompous it needed its own chair: RECOVERED FROM AVIAN TENDENCIES (REMAINS DELIGHTFUL). Noreen framed it. Paddy offered a scone on the house. Mrs. Flaherty placed a very small, very sensible beret on Henrietta and said, “You’re the inspector now, love.”

The Supreme Leader compiled a report for whichever distant management cares for such things. It read:

SUBJECT: BALLYKILLDUFF

STATUS: NOT CONQUERED.

REASON: CAKE, COMMUNITY, AND THE INEXPLICABLE SATISFACTION OF DOING SOME GOOD.

RECOMMENDATION: FURTHER FIELD RESEARCH. BRING TUPPERWARE.

He delivered the report with all appropriate gravitas, then quietly ordered a second slice of Hero Cluck Cake and asked whether one could learn to waltz while remaining essentially a tank. (Answer: Yes. Ballykillduff waltzes with everything.)

As for Zog, he resumed “patrol,” which now entailed standing at a scenic point, rotating ominously, and making sure the hens got across the road safely, the fox stayed moustacheless, and tourists left the Coop as tidy as they found it. He wore his potato-ribbon on Sundays.

Sometimes, when the wind is right and the village has eaten sufficiently, you can hear him hum a tune like a kettle that’s found contentment. Sometimes he visits the National Hen Observatory and reads aloud from The Eggistentialists: Essays on Being and Breakfast, while Henrietta underlines the good bits with her foot.

And sometimes, late evening, he rolls to the hedgerow and thinks about the night of the storm, about being a neighbour, about the way a village holds together in the dark. He wonders if this is what home feels like, and decides yes, probably, in the vicinity of scones.

Epilogue: A Final Cluck

A month later, on a day so gentle it could pass for a cushion, Ballykillduff held a small ceremony. Noreen presented Zog with the Order of the Feather, a medal shaped like a perfectly ridiculous plume. The Supreme Leader officiated (which is like threatening but with better diction). Mrs. Flaherty said a few words. Paddy attempted to rhyme Dalek with caramel and got away with it.

Henrietta delivered the keynote address, which was mostly clucking but had footnotes. The fox lurked at the edge of the crowd pretending he had always wanted to go vegan.

Zog accepted the medal. He considered the crowd, the Cups of Tea, the tasteful bunting, the hum of a village modestly proud of itself. He lifted his plunger, found his voice, and said:

“STATEMENT: THE CASE OF THE BIRD FLU IS… MOSTLY CLOSED. COROLLARY: I REMAIN… ZOG. ADDENDUM: BALLYKILLDUFF IS DESIGNATED… NON-EXTERMINABLE. JUSTIFICATION: CAKE. AND ALSO… LOVE.” He paused, let the word sit, felt it purr. “ACKNOWLEDGED.”

A cheer rose that made the crows forgive everything. Henrietta pecked the medal once for luck. The Supreme Leader, who had begun to enjoy this ridiculous planet against his better judgement, allowed himself the faintest, tiniest, scientifically undetectable smile.

The hens went home to lay the future. Zog resumed patrol. The wind pushed clouds over the fields like sheep. Ballykillduff went back to its generous strangeness.

And somewhere beyond the hedgerow, under a marginally better moustache, a fox practiced saying good afternoon to a chicken without sounding like he meant good appetiser. Progress is a sort of miracle, after all.

The End (for now, unless we are having dessert).