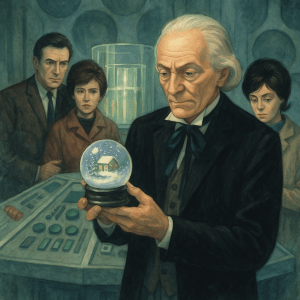

Doctor Who and the Snowglobe of Eternity

The Snowglobe of Eternity feels like it could have slotted right into Season One or Two — eerie, self-contained, with a festive backdrop but an alien heart. It’s drafted in the 1963 Doctor Who style, with chapters laid out as if it were a missing serial.

Doctor Who and the Snowglobe of Eternity

A novelisation in the spirit of the classic paperbacks—clear, pacey, a little eerie, and just a touch Christmassy.

Chapter One

The Toymaker’s Secret

The TARDIS coughed and wheezed in that obstinate way which always made Ian Chesterton think of old buses on winter mornings. A moment later the central column sank with a final, satisfied sigh. Silence returned—if the soft hum of impossible machinery could be called silence.

Barbara Wright drew her coat tighter and glanced at the scanner. A dark windowpane filled it, rimed with frost. Beyond: falling snow and a suggestion of a lamplit street. “London?” she wondered aloud.

The Doctor stood very still at the console, chin tucked into his collar, eyes bright under white brows. “Might be,” he said, as if the word were a rebuke. “Might be not. Hm!”

Susan was already at the doors. “Please, Grandfather! It’s snowing.”

The Doctor sniffed, considering. “Very well. But no wandering off. We observe. We do not tamper.”

They stepped out into a narrow Victorian lane where the snow fell with purposeful, muffling diligence. Gas lamps haloed the air. The buildings leaned like old men conferring. A bow-fronted shop stood opposite, its large window displaying dolls, tin soldiers, and rocking horses arranged in ranks, as if awaiting parade. Above the door a hand-painted sign read—simply—TOYS.

“It’s like a Christmas card,” Barbara breathed.

Susan pressed her nose to the cold glass and laughed softly at her own reflection. Inside, a single lamp burned, throwing long shadows over polished wood and varnished smiles. The door yielded to Ian’s careful push, and a bell gave a genteel tinkle, surprised to be woken.

The shop smelt of wood shavings and glue. Ranks of nutcrackers stood on a shelf like a red-and-gold regiment. A rocking horse stared eternally mid-gallop. Somewhere deeper in the shop a small fire popped behind a grate. The place felt warm and friendly, yet the warmth seemed to falter at the edges, as though something were standing just out of sight, breathing in the heat.

Susan drifted towards the counter. An object there caught and held her. It was a snowglobe of uncommon size, set into a cradle of black wood. Within, a tiny village slept under an endless fall of white; there were minuscule cottages, a church with a steeple so fine it could have been threaded, and—she leaned closer, frowning—a shadow that moved along the lane.

“Careful, Susan,” Barbara said, though she did not take her own eyes from the thing.

Ian rapped his knuckles on the counter, the way schoolboys greet an empty classroom. “Hello?”

A shape detached itself from the back room. The toymaker was a man of indeterminate age with delicate, almost transparent hands and a face made for kindness. He wore a black waistcoat that had known better years, and a watch-chain glinted at his middle. He smiled as if he had been expecting them.

“Good evening,” he said. “Do come in. The snow has a habit of keeping honest folk at home, but Christmas Eve deserves company.”

The Doctor’s eyes narrowed. He had a habit of looking at people as if they were a puzzle that might yet solve itself. “And good evening to you, sir,” he returned, with courtly abruptness. “A charming establishment. Hm. Quite… charming.”

Susan’s fingers hovered above the globe. “It’s beautiful.”

The toymaker’s smile deepened. “Ah. You admire my prize. The snowglobe contains the spirit of Christmas, or so I tell the children. In truth, it contains—well.” He stopped himself neatly. “Forgive an old man his patter.”

Barbara bent closer. She was about to say that the detail was remarkable when the tiny figure in the globe stopped, turned, and raised a hand, as if in greeting—or warning.

She straightened. “Doctor?”

The old man did not move to the counter. He stood in the middle of the shop, hands folded, and addressed the toymaker without taking his eyes off the globe. “Where did you get this?”

“Acquire. Such things are never owned,” said the toymaker. “It came to me as the first snow fell, many winters ago. I have cleaned it, polished it, and kept it from harm. That is all.”

Susan shook the globe, very gently—no more than a tremor. The flakes within whirled. A storm took hold. Tiny shutters banged. The little figure ran for a doorway and vanished. In the heart of the globe something seemed to cry out, though no sound reached their ears.

The Doctor’s voice cracked like a cane on a school desk. “Put it down, child!”

Susan set it back, startled and a little ashamed. “I didn’t mean—”

“No, no,” soothed the toymaker. “No harm done.” His kindly eyes were fixed on Susan now. The look had weight. “But you must be careful with glass at Christmastime. It remembers.”

Ian, who had faced Daleks and cavemen and worse, felt the hairs rise on his neck at that simple sentence. He leaned in to Barbara. “It remembers?”

“Sh,” she whispered. “Listen.”

The Doctor’s hands were in his lapels. “I do not care for conjurer’s talk, sir. This is a chronon pocket, a sealed fold of time. Who placed those lives within?”

“Lives?” Barbara said instinctively.

“Open your eyes, my dear,” the Doctor snapped. “The detail is not mere craft. Observe the breath in the air, the eddies stamped by feet too small to carve. These are no toys. They are people.”

The toymaker’s smile became so small it was almost not there at all. “You see more than most. Yes. People. Prisoners of winter. They came with the glass, or the glass with them. One grows forgetful of the order of things when winter lingers.”

The fire cracked. The shop seemed to lean closer to their conversation. Susan’s gaze was caught and held by the tiny church. A pinprick of light glowed at its window, steady amidst the storm.

“Grandfather,” she said, softer than the snow. “They’re waving.”

“What?” Ian stepped to her side. Within the glass, tiny figures stood in the street, faces lifted. Their mouths opened and closed, shaping words that would not cross the barrier.

“Help us,” Barbara breathed, reading the shapes.

Susan reached—only to pull back as the toymaker’s hand appeared near hers. The hand was not cold, precisely, but the air fell in temperature around it. He tapped the globe once, and the figures flinched. “Politeness first,” he murmured. “We must ask the Doctor if he will help them. He is good at opening doors, I think.”

“My dear sir,” the Doctor said, voice crisp with outrage and curiosity, “you ask as though the key were mine.”

The toymaker lifted a small silver key on a chain from his waistcoat. Its teeth were too fine, like a snowflake frozen in metal. “And as though the lock were here.” He turned the globe within its cradle. A dark keyhole yawned at the base, where black wood met glass.

“Don’t,” Barbara said at once.

Ian had begun to circle the counter. “Step away from it.”

The toymaker’s eyes glittered. “Eternity is a very long time,” he said softly. “The door swings in both directions.”

Susan’s name rose in Barbara’s throat without warning, a sudden fear like ice-water. She turned—

—and saw that Susan was gone.

For a heartbeat the shop was only a shop: wood and brass and ordinary quiet. Then a tiny shape flickered in the globe where there had been none moments before. A new figure stumbled into Wintershame’s lane. A girl in a too-large coat, dark hair already white with snow.

Barbara’s cry became the only sound in the world. “Susan!”

The Doctor lunged to the counter with a speed that belied his age. His breath fogged the glass. Within, Susan lifted her face and shouted a name that reached them as nothing more than a tremor in the snow.

The toymaker lowered the key towards the lock.

The Doctor did not look up. “If you turn that,” he said, voice very soft, “you unleash far more than you understand.”

The toymaker’s smile returned, bright and brittle. “Doctor,” he said, and in the single word there was something that was not kindness at all, “I understand perfectly.”

The key slid home with a delicate, dreadful click.

Chapter Two

The Frozen Village

Susan fought for breath as the wind took her. The cold was not simply cold; it was a presence, eager and intent, that pressed at her mouth and eyes as though to fill her up and make a home inside her.

“Grandfather?” she called. Her voice did not carry. It seemed to fold in on itself and drop at her feet like a broken toy.

A hand slipped into hers. She turned to find a girl her own age, pale-eyed and thin as a candle. The girl put one finger to her lips. “Don’t shout,” she said. “It wakes the storm.”

“What is this place?” Susan whispered, and only then did the world allow a sliver of sound to pass.

“Wintershame,” the girl said. “Where time forgot to end.”

They moved beneath the lee of a low wall. Beyond, a small square lay smothered under white. Houses hunched against the wind. A stall stood abandoned, its apples furred with frost. From the church a bell tolled once, a slow note that seemed to look over its shoulder before it faded.

“Where are your people?” Susan asked. “Your family?”

The girl’s mouth tilted. “They are all here. And nowhere. We don’t speak much now. When we do, the storm listens and copies us. It sings our songs until we forget the words belong to us.”

She tugged Susan’s hand and led her along the lane. Each step creaked. The snow came thick and fine, like sifted flour. Faces flickered behind the glass of windows then vanished, spooked animals in their burrows.

“What’s your name?” Susan said.

The girl thought about it for too long. “I had one.”

Inside the toyshop, the Doctor was all quick decisions and sharp angles. “Barbara, to the door. If this escalates into the street we shall have more problems than we can comfortably solve. Chesterton—!”

“I’ve got him,” Ian said grimly, and caught the toymaker’s wrist before the man could twist the key further. The contact hurt. Ian snatched his hand back, surprised; the toymaker’s flesh had felt like packed snow under a thin layer of skin.

“I merely propose to open a door,” the toymaker murmured. “You should thank me. No visitor likes to be left out in the cold.”

The Doctor’s glare could have scalded tea. “You’re not opening anything.”

“You cannot keep it contained forever,” the toymaker replied. His kindness had the weary certainty of a sermon repeated each week to the same congregation. “Eternity doesn’t tire.”

He lifted the chain so the light shivered along the silver teeth. The globe seemed to pulse faintly in answer. The Doctor’s hands tightened on his lapels.

In Wintershame the wind changed. It became a hiss, like something whispering in a neighbouring room. Susan and the girl ducked under the eaves of the church porch. The door stood ajar. Within, impossible heat breathed across the threshold, hot as summer fields. Susan reached toward it and felt the warmth slide away from her fingers. The church was not warm; the idea of warmth had been put there like a picture on a wall.

Figures sat in the pews, hands folded, faces glazed with frost. Their mouths worked slowly, prayer without words. Susan’s chest tightened.

“Why do you stay here?” she asked.

“Where else is there?” said the girl. “The snow does not end. It is not a season. It is a story being told over and over, and it does not like a different ending.”

The bell tolled again. It sounded almost surprised to hear itself.

A heavy tread shook the porch step. Susan turned and flinched. Figures emerged from the drifts: toy soldiers taller than any man, uniforms painted on, eyes the flat blue of winter skies. Their jaws unhinged with a wooden crack as they marched. From the open mouths poured a thin spill of snow as fine as ash.

“The toymaker,” Susan whispered.

“No,” said the girl. “They belong to the snow.”

The Doctor had seen enough. He moved to the counter and bent over the globe, peering as if his gaze could compel a better ending. “Susan,” he said softly, the single word both name and command. Then, without taking his eyes from the glass, he spoke to the toymaker. “Who placed them there?”

“You still think in lines. Before and after,” the toymaker said. “One winter the globe was empty. Another, it was not. One shop was warm. Another, it was cold. I remember both.”

“Unhelpful,” the Doctor muttered, and tugged the cradle, testing weight and angle. The key was still in the lock. “If I cannot extract you, child, I must bring the prison closer.”

Barbara’s breath fogged in the cold that now crept steadily across the counter and down its legs. “Doctor, the glass—look.”

Hair-thin cracks were spreading across the globe. With each one the shop grew colder and the wind grew louder, though the window panes did not rattle and the door did not move. The storm was inside the glass and inside the shop at once, like a thought forming in two minds.

Ian shifted his weight and picked up the nearest solid object—a wooden nutcracker. It looked disarmingly cheerful. “If it comes to it,” he said, attempting brisk humour, “I’ve always fancied myself against a regiment of tin soldiers.”

“Do refrain from jokes, Chesterton,” the Doctor snapped. “They encourage the universe.”

The toymaker closed his thin fingers around the key and turned it.

The globe did not open. It cracked.

Snow began to leak through the wound.

Chapter Three

The Storm Breaks

The first flakes that escaped were ordinary enough—cold, melting on skin. The next carried a whisper. Then came a drift that did not melt at all. It curled along the edge of the counter, reached the floor, and began to creep, delicate and purposeful, towards the aisles.

The shelves creaked. Heads turned. A row of dolls glanced left as one, eyes following in unison with soft clicks. A jack-in-the-box sprang open and stared over its painted ruff, astonished to find itself awake. The rocking horse stretched fractionally into its gallop.

Barbara took three quick steps back. “Ian—”

“I see them,” he said grimly, and squared up in front of her, nutcracker aloft like a cudgel.

The toymaker’s expression emptied, and suddenly he seemed not old at all but very young and terribly tired. “It remembers,” he said again, and smiled. “And now so will you.”

Something moved beneath his skin. It was the smallest of ripples, a shimmer like sleet across a puddle. His cheekbones sharpened. His eyes seemed to acquire edges.

The Doctor’s voice was very calm. “You are not a master of it.”

“Master?” The toymaker’s laugh was the clink of ice in a glass. “No. Prisoner. Warden. What is the difference when the door is snow and the lock is time?”

The globe flared with sudden light. Inside, Wintershame yawned like a mouth. Susan ran with the girl between the drifting ranks of toy soldiers. Their wooden feet thudded in time, a drumbeat that pecked at the nerves. Snow rattled against the church windows, then poured through the coloured glass in a glittering torrent.

The girl stumbled. Susan caught her. “Come on!”

The girl smiled without teeth. “You don’t belong here,” she said. “I do.”

“Don’t say that!” Susan snapped, sudden tears stinging her eyes. “No one belongs in a cage.”

They burst out of the church as a steeple bell tolled backwards. Overhead the sky was crazed with hairline fractures. Through them—just for a moment—Susan saw the Doctor’s face beyond glass; the lines around his mouth tight, the eyes furious and fearful. She cried out. The wind took the cry and folded it into its own whispering voice.

In the shop Ian caught the first of the marching toys by the collar and heaved. The wooden soldier staggered, pivoted with that unnerving puppet’s grace, and came on again, bayonet gleaming with rime. Ian swung the nutcracker and smashed it aside. It came back with its head twisted at a sick angle.

Barbara snatched a curtain pole from a display and jabbed another in the chest. It split cleanly. There was nothing inside—only compacted snow, so cold it burned her hands even through her gloves. She yelped and dropped the pole.

“Barbara!” Ian shoved her back and planted himself between her and the advancing toys.

“Efficient, these things,” the Doctor muttered. “The storm wears what the world provides. It steals patterns. Soldiers. Carols. Christmas. Hm!” He snapped his gaze to the toymaker. “And you—what did you promise it, eh? A world willing to stand still for it once a year?”

The toymaker’s face was smooth now, all warmth pared away. “I promised it company,” he said. “And in return it promised me time without end.”

“Then you are a bigger fool than I took you for,” the Doctor said with real pity.

The glass did not shatter all at once. It flowered; an opening that was also a wound. The shop filled with a sound like breath drawn in. The storm came through.

And London—obedient as a stage that knows its part—accepted its cue.

Chapter Four

The Eternal Blizzard

It was Christmas Eve, 1863. The first flakes that fell on Fleet Street that night went almost unnoticed. The second flurry made footmen draw up coat collars and newsboys stamp and curse. By the time the bells struck nine, a third had settled along the kerbs like lace. Then the snow ceased to behave like weather and became an event.

Hansom cabs froze mid-turn, horses snorting steam that turned to smoke and then to nothing. Carollers forgot the words to God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen and found themselves singing a phrase back and forth until the phrase sang itself. The Thames knitted a thin, spiteful skin of ice and the lamps along the Embankment bloomed halos, as if the air itself were glass.

Susan staggered into an alley and leaned on a lamppost, coughing frost. The city was a blur of white and lamplight and fear. Near St Paul’s a choir of small boys were trying to run, hampered by stiff boots and stiffer cold. A circle of toy soldiers marched around them with idiot patience, bayonets pricking a ring into the snow.

Susan darted forward and then froze herself—not with cold, but with a fear that arrived from nowhere and settled on her like a second skin. She felt, very clearly, the story the snow wanted to tell: a Christmas that went on and on, perfectly repeated, never completed. Voices would sing until they were only patterns on the air and patterns wore out nothing.

She swallowed, tasted iron. “No,” she said very softly, to the snow, to herself. “No.”

Back at the shop the Doctor worked. The room around him had become a small battlefield. Toys juddered and lurched. Frost crawled along the walls in intricate ferns. Barbara helped the injured, which was to say she collected the dropped fragments of a world and frowned at them, daring them to make sense.

The Doctor stood over the ruined globe. He had gathered its larger shards into a tight cluster, arranging them with an odd, almost tender precision. “If a prison it was, a prison it shall be,” he muttered. “A story, yes. Very well—we tell a different one.”

Ian, flushed and panting, risked a look over his shoulder. “What are you doing, Doctor?”

“Denying the storm its pattern,” the Doctor snapped. “It wants a carol? I shall give it a silence. It wants a parade? We shall break step.”

He glanced at the toymaker, who was no longer entirely a man and not yet entirely a statue. His hair sparkled with frost. His eyes had gone pale as old glass. “And we shall give it a warden willing to stay.”

The toymaker smiled with his whole face for the first time. “At last,” he whispered. “A promise kept.”

The Doctor brought the shards together with a swift, decisive movement.

Light rushed inwards. The sound that followed was not a sound a human throat could make. It was a subtraction—the city exhaling a breath it had been holding since before the first flake fell.

At St Paul’s the toy soldiers stopped. Their heads tilted, wooden jaws opening as if to sing. They collapsed instead, first to their knees and then to powder, uniforms and all. The boys’ hymn turned into a gasp and then into the delighted shout of children released from school.

Susan looked up. The girl from Wintershame stood at the edge of the square, her hair a crown of snow. She smiled. It made her look very young.

“Goodbye, Susan,” she said. Her voice was soft and certain, the way a candle’s flame seems to understand itself.

Susan stumbled towards her. “Come with me!”

The girl shook her head. “I belong where the story ends.”

She lifted her face to the storm and stepped forward. The wind took her up as snowflake after snowflake until nothing remained but a suggestion of a hand in the flurry and then not even that.

The city darkened as if a cloud had passed the sun, though it was night and there was no sun to pass. Light poured backwards towards the toyshop, to the counter, to the cradle where the Doctor held two jagged halves of a glass world and made a whole of them.

The blizzard withdrew like a tide.

Chapter Five

The Longest Winter

Dawn discovered London looking innocent. The snow lay thick but quiet, a blanket recently smoothed by a careful hand. Carollers rubbed their eyes and laughed at nothing. A constable blinked on a corner and wondered where the last hour had gone. Children poked the snow with sticks and declared it the very best sort for men and missiles.

Barbara and Ian helped a man to his feet near the toyshop and persuaded him that, yes, of course, his collar always buttoned on that side and, no, there had been no peculiar noises in the night—only the wind. Barbara had a way of making impossible things sound reasonable. Ian had a way of looking as if he could lift a piano if it refused to behave. Between them they shepherded doubt into safer channels.

Susan walked ahead, alone for a little while, with the winter sun in her eyes. She felt simultaneously very young and very old. Snow squeaked under her boots. Somewhere, faintly, a bell chimed. It sounded ordinary again, which was a relief and a disappointment.

The shop door hung open on a ruined room. Shelves had split. A rocking horse lay at an angle that made Barbara wince. The counter was burn-marked where light had been too bright. On it sat a snowglobe whole and unremarkable, flakes drifting lazily within.

The toymaker was nowhere.

The Doctor stood very still, hands on either side of the globe, shoulders bent in a posture that could have been weariness or prayer. He did not touch the glass. He seemed unwilling to break the spell of not touching.

“Well?” Ian asked at last, gentle despite himself.

The Doctor lifted the globe and turned it so the glass caught the pallid morning light. “Yes,” he said, drawing the word out, thoughtful. “Yes, I thought as much. The prison has knitted itself. Smaller. Weaker at the seams.”

“Could it break again?” Barbara asked.

“All things can break,” the Doctor said. Then, because Susan’s face had grown a shade paler, he added, in a softer voice, “But not today.”

He slipped the globe under his cloak with a deftness that suggested he had not decided whether it was for safekeeping or simply out of sight, out of mind. Barbara watched him, understanding entirely and not at all.

They walked back through a city rubbing sleep from its eyes. A woman swept a doorstep with relish. A boy pulled his cap down and threw a snowball, missing magnificently. A stall-keeper shook frost from apples and tried to remember the price he had always charged.

“Life carries on,” Barbara said. “As if nothing happened.”

The Doctor’s reply was sharper than he intended. “History forgets, my dear. It forgets more than it remembers.” He sighed then, and the sharpness leached away. “That is a mercy. And a danger.”

By the TARDIS the snow stood unsullied, as if it, at least, knew better than to try its tricks on a police box. Susan lingered with Barbara while Ian fussed cheerfully with the lock, as if it were a stubborn classroom cupboard.

“Are you all right?” Barbara asked.

Susan nodded, then shook her head, then nodded again. “She stayed,” she said. “So I could go. I don’t even know her name.”

Barbara slipped an arm around her. “You’ll remember her all the same.”

Inside, the TARDIS felt especially warm. The console lights winked companionably. Ian patted the panels the way a man pats a horse that has brought him home. The Doctor, at the far side of the room, took the snowglobe from his cloak and held it up. The flakes inside turned and turned, never quite settling, as if they were undecided about the laws of gravity.

For a heartbeat Susan thought she saw a face in the glass—the ghost of a girl smiling, and then only her own reflection caught in the curve.

The Doctor tucked the globe away into some impossible recess and rested his palm on the console. “Yes,” he murmured, almost to himself. “The snow will sleep. But eternity—hm!—eternity is a very long winter indeed.”

He threw a switch with familiar authority. The central column rose and fell. The groan of ancient engines filled the room—comforting now, like an old song you never quite forget even when the words escape you.

Outside, London’s morning went on. Inside, the travellers moved on to somewhere and somewhen else, leaving behind a tidy street, a ruined shop, and a glass world that held its breath.

And if, on certain Christmas Eves, a faint whisper could be heard when the wind was wrong and the lamps burned low—well, London is an old city. It has room for a few stories, and occasionally one story keeps a corner for itself, where the snow falls a little thicker and the bells sound as if they are listening.

THE END