The Last Trick-or-Treat

The Last Trick-or-Treat

The Last Trick-or-Treat (A Ballad of the Twelfth Knock)

Prologue: Four Days Before (Saturday, October 27, 2025)

The warning doesn’t arrive all at once. It seeps.

In Ballykillduff, County Carlow, a chalk scrawl appears below a hopscotch grid by the school gates. Maeve Byrne sees it when she parks for the farmers’ market—letters clumsy as a child’s, but written with a steadiness that pricks her skin:

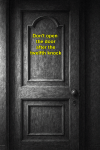

DON’T OPEN THE DOOR AFTER THE TWELFTH KNOCK.

In Columbus, Ohio, Janelle’s ring camera records fourteen seconds of empty porch and a sound like careful knuckles on wood. She counts out loud while the clip plays back in her editing software, gooseflesh rising with each beat. One-two-three… At twelve, the image tears. At thirteen, the file corrupts. At fourteen, her computer crashes. When she reboots, the clip is gone, but her mouth still remembers counting.

In Higashimurayama, on the western edge of Tokyo, Kaito reads a thread on a niche forum for urban folklore. A user named MoonOwl shares a poem supposedly translated from an Edo-era diary:

Do not rise to the mirror’s hand,

Do not bow to borrowed faces,

Twelve times the night will ask,

Thirteen times it will take.

The post is promptly removed for “fabricated citations.”

In Melbourne, paramedic Arun spots a line of pumpkins outside a cafe on Sydney Road. Overnight they’ve bloated, sagging into black slush. The owner swears they were fine at close.

In each place, someone shrugs and someone laughs and someone—just one—feels an old animal in the ribcage stir and whisper: Listen.

Chapter One: Ireland — “The Hollow Knock”

Maeve Byrne has never liked Halloween. She loves autumn—the low sun slanting across stubble fields, steam rising from mugs, the small exhilaration of lighting the fire as dusk creeps early—but not the holiday. Not the masks, not the candy chaos, not the gates unlatching between sense and nonsense.

Her son Finn, nine, loves all of it.

“Can we do the full round this year?” he asks at breakfast on the 31st, hair a bristle of excitement. His ghost costume (a pillowcase with painted eyes) lies folded on the chair, haloed by cereal dust.

“We’ll see,” Maeve says, because “no” feels like boarding up a window the sun still wants to use. She has seen the posts, the jokes, the headline chyrons about The Twelfth Knock. She has seen the chalk by the school. She has told herself: Mass hysteria. Viral fun. Old wives dressed in pixels.

By afternoon the sky is pewter. A wind like a cool hand passes over the fields. Maeve strings three pumpkins on the stone wall. She leaves a bowl of sweets out with a note—Take two, happy Halloween!—and feels both foolish and relieved, like someone who has halfway listened to a superstition and can therefore stop listening altogether.

At six-thirty, the first children come. The bowl empties in polite handfuls. Finn bounces at the window.

“Please, Mam. Just Clancy’s Road and back.”

“We’ll go early,” Maeve says. “And we’ll be home early.”

They step out into a Ballykillduff evening where the hedges are ink lines and the fields are breathing. The road curves, familiar as a prayer. Laughter stitches across the dark. Somewhere, a tractor grumbles. Somewhere else, a dog decides every witch hat is the end of days.

On Clancy’s Road, Mrs. Harkin in her witch wig spoons sweets with her ladle and says, “Twelve knocks. The radio says not to take the mickey with it. Anyway, I’m not counting. I’m throwing them out the window if needs be.”

At number eleven, a paper ghost spins in the wind. At number thirteen, a plastic skeleton dangles like a bad decision. Finn tugs Maeve’s sleeve. “Can we go to the new house at the end? The one with the lanterns?”

Maeve hesitates, then nods. The new house sits where the lane dips, one light in the porch, a line of little lanterns like foxfire. The sign on the gate says RILEYS. Finn trots ahead, pillowcase ghost in one fist.

The knocker gleams. Finn raps once, twice, three times, counting loudly because that is a child’s magic. “Four! Five! Six!—”

“Don’t,” Maeve says, too sharply. Her voice startles the night.

“Seven,” Finn whispers, defiant.

The door opens at seven. A woman in a cardigan smiles, face soft with relief. “Oh, thank God—sorry, I mean—I’ve been sitting here counting my own heartbeat. You’re my first actual trick-or-treaters. Take… take as much as you like.”

They do. They say thanks. They wave. They leave lanterns behind and walk up the lane, and the hedge wind sounds almost like breath counting: one—two—three—

Maeve wonders, on the walk home, when her hands started shaking. She tells herself it’s the cold. She tells herself not to count. She tells herself that if she doesn’t count, the number can’t happen to her.

When the first knock comes to their own door at eight forty-one, it is firm but polite. Finn looks up, eyes bright. Maeve looks at the clock. “We’ll just leave the bowl, yeah?”

The second knock is the same. The third too. After the fourth, Finn whispers, “Mam?” After the fifth, the house seems to lean.

At the sixth, Maeve takes Finn’s hand and leads him into the sitting room. She turns off the lamp. She draws the curtains. In the hallway the seventh knock lands, then the eighth, then nine-ten-eleven—

“Don’t open,” she breathes, as much to herself as to Finn.

Silence then, a long sip of it. For a second Maeve thinks: There. It’s going away. It has counted wrong and gone away.

The twelfth knock is gentle. It is the careful tap of a child taught to mind their manners. It is so soft that it feels like a courtesy, like the night saying please.

“Mam?” Finn whispers again, smaller.

They do not open.

They listen. And somewhere beyond the door—so close it might be on the wood, so far it could be in the hedge—something smiles without teeth.

Chapter Two: United States — “Content Warning”

Janelle runs a channel that started with home DIY, then veered into weird history (“Five Urban Legends You Can Fact-Check”) and now drifts toward the liminal seam where what if? rubs against oh, no. Her most popular video is “Why Your Doorbell Hates Halloween,” a playful takedown of motion-sensor ghost clips. The comments are full of skeletal emojis and neighbor drama.

On the morning of October 31, she films a quick explainer about the Twelfth Knock. She debunks. She jokes. She pulls up police pressers that say “Please don’t prank call 911” and “Keep porch lights on for safety.” She says, in her warm Ohio cadence, “The only thing visiting your porch is the same cavity goblins that show up every year.”

At dusk, she decides to do a live porch cam—fun, communal, zero stakes. The chat scrolls with costumes. Somebody is a sentient peanut. Somebody else is a haunted PayPal dispute. The doorbell brings a bumblebee, two vampires, a toddler dinosaur whose roar translates to “sticker.”

At 8:19 PM, the chat slows. Janelle feels it, as one feels a room change when a secret walks in.

“Okay,” she says, keeping tone bouncy. “Power ranking of worst candy: licorice is not candy, it’s punishment, and—”

Knock.

She swivels to the camera. “We have a knocker,” she says, theatrically. “One.”

The chat spools out a chain of 1s.

Knock. Two. Knock. Three. The knocks are evenly spaced, courteous. The porch is empty on her monitor—only a stripe of suburban dark, the smear of a passing car, a moth battering at the lens.

“Somebody’s messing with me,” Janelle says, laughing. “It’s fine.”

Four. Five. Six.

Somewhere between seven and eight, the porch light seems to thin, like fog inside a bulb. The frame grain thickens. Janelle leans in. She has the odd sensation of looking into a fishtank that is looking back.

“Nine,” she says, heartbeat audible in her own voice.

Ten. The chat is now a wall of DO NOT OPEN and girl stop and is that a person??—though the porch stays empty.

Eleven.

“This is silly,” Janelle tells herself. She stands. She sets a bowl on the floor by the threshold, slides it with her foot until it bumps the door. She says brightly, to the stream and the night, “Help yourself,” and takes three steps back.

…Twelve.

The door doesn’t move. The camera glitches once, twice, then steadies. Janelle inhales and realizes she has been holding her breath for a long time, enough for her vision to sparkle.

On screen, something leans briefly into the far edge of the lens. It is not a face. It is a shape like the idea of a face, rendered from shadow the way a child draws a person: too much mouth, too little everything else. Its mouth opens as if to say thank you—but what comes out is a sound like knuckles tapping wood from very far away.

The stream goes black.

In the silence that follows, Janelle’s kitchen clock performs its good, stupid duty. It ticks. It ticks. It ticks.

Janelle does not open the door. She sits on the floor, back against the cabinet, phone in both hands, thumb hovering over 911, then hovering over her mother’s number instead, because some nights you know what you need is not police but someone who remembers you before you were brave.

She texts: Mom? You up?

On the porch, wrapped candies in the bowl begin—so gently—to slide into the dark, one by one, as if each sweet decides where it belongs.

Chapter Three: Japan — “Borrowed Faces”

Kaito’s grandmother keeps the old holidays soft and living. Obon, Setsubun, the quiet remembrances she enacts at the butsudan with a casual intimacy that makes the young feel included rather than burdened. Halloween, she says, is “borrowed,” with a smile not unkind.

But even borrowed faces can bite.

By evening, trick-or-treaters in their apartment block have finished the rounds. Kaito’s grandmother has laid out taiyaki in addition to candy, which made her extremely popular with a boy dressed as a traffic cone. The city is a spill of neon and breath and festival posters. The corridor smells faintly of curry.

At nine, a neighbor’s baby cries, then hiccups into sleep. At nine-fifteen, distant fireworks mimic both joy and gunfire. At nine-thirty, the elevator chime dings uselessly at every floor. At nine-forty, Kaito sees a post on a Japanese news app—not a story yet, just a badge: “Multiple reports of door-knocking prank escalations. Please remain calm.”

He tells his grandmother about the Twelfth Knock in simple terms. She nods, absorbing the superstition into her wide museum of them. “We have an old saying,” she says, eyes on the dark TV screen. “A guest who counts will not leave through the door they entered.”

“What does that mean?” Kaito asks.

She shrugs, mouth tugging. “It means: the night does not love arithmetic.”

The first knock comes at nine-fifty-eight, so polite it might be a relative. Kaito stands. His grandmother tilts her head. The second is the same. The third too. He remembers the thread he read—the poem, the removal—and hears in it the spine of this moment, as if a story has caught them by the sleeve.

“Who could it be?” he says, even as he decides not to check the peephole.

By six, the corridor air feels colder, as if the building has inhaled. At seven, the light in the ceiling hums at a different pitch. At eight, Kaito hears footsteps not in the hallway but in the walls—a trick of sound, like rain traveling along pipes. At nine, he thinks he hears his mother’s voice on the other side of the door saying his name the way she did when his stomach cramped at five years old.

“Kaito,” his grandmother says, soft warning. “Borrowed faces.”

At ten, his phone vibrates with a push alert in English, something algorithmic deciding now is a good time to show him the flattening world: BREAKING: Halloween disturbances reported in multiple countries. The thumbnail is a blank porch.

Eleven.

He counts the last one silently, teeth pressed to tongue, as if the number will cut him if it enters the air.

Twelve.

Nothing moves. He imagines the hallway full of masked children, then stripped of them, then of people who are not children at all but wearing a language of childhood like a coat inside out. The tighter he imagines, the more the form escapes.

“Tea,” his grandmother says, almost brisk, and so they make tea. The ritual warms time. On the counter the steam is visible in the new cold. When they set the cups down on the table, the apartment light flickers, then steadies.

Through the door, something exhales a breath it does not need.

Chapter Four: Australia — “The Ambulance Will Be Right There”

Arun learned long ago that advice is triage you do with your mouth. Tell people what to do with their hands and you keep their heads from splitting open. On nights like New Year’s or Grand Final, he becomes a river moving toward everything broken. Halloween in Melbourne isn’t the saturation it is in the States, but the city likes its masks. Tonight already has its share of “fell through a costume,” “cut by bottle,” “ate something glowing, please advise.”

At 10:56 PM, the CAD system lights with calls tagged Welfare — Door, Caller Frightened. They stack like tiles. The notes under each are copy/paste: Knocking in sets of 12. Caller reports “empty porch” or “shadow.” Advise to remain inside.

Arun feels an old prickle. He thinks of the cafe pumpkins; how they looked less like fruit gone off and more like something had licked them clean from the inside.

He keys his radio. “Control, 312 en route to… any of the above.” Humor is one way to signal to yourself that the world is still measurable.

“Copy, 312,” the dispatcher says, the way a person says Please don’t make me say what is happening out loud. “Be advised, law is requesting we do not approach doors if active knocks are occurring.”

“Received,” Arun says. “Do we have a definition for ‘active’?”

“Affirm—if the caller can count them,” Control says. “If they can’t count, do not approach.”

He and his partner, Rosie, look at each other and do the wordless exchange of colleagues who have been present for impossible things: I’m here. You’re here. Okay.

They arrive to a fibro house where a teenager with a busted knee sits on the couch, crying, because the door knocked twelve times while he waited for them. He counted. He did not open. He then fell in the hallway running away from nothing.

Arun tends the knee (not bad), checks vitals (fine), does the questions (name, allergies, questions that are a blanket over both of them). “You did well,” he says, and means it. The boy nods, a quick bird motion. In the kitchen, a bowl of fun-sized chocolate bars is inverted, as if it turned over by itself and then thought better of it.

“Next,” Rosie says gently, and they go back into the night, which is now full of calls, and the radio sounds like rain hitting leaves.

At 11:59, Arun parks on a quiet street not because he’s on a break but because the car misbehaves with the odd greasy clunk it gets in damp air. In the seat, he counts his own breath. He tells himself: Halloween will end. Midnight is a sort of door. The night must leave through it.

Inside the houses—the street has eleven of them, he counts automatically—someone makes tea. Someone hides in a laundry with the dog. Someone watches their smart doorbell cycle through excellent nothing.

At 12:00 AM exactly, the city sighs. The calls change tags to No Answer On Call Back one after another, as if the server itself has learned the word gone.

Arun and Rosie stare at their screens and then at each other. “Midnight,” she says.

He nods. “Midnight.”

From somewhere close, laughter rises—not kids, not drunk adults—laughter like a zipper unzipping fabric that had been sewn intentionally shut.

They do not open any doors. They do not get out of the car. They sit. They count the streetlights. They count the breaths. They count, and the counting is a spell that keeps them in a car where their hands can hold something solid.

Chapter Five: Cross-Cut — “Twelve”

Ireland. The twelfth knock hushes the Byrne house to its bones. Maeve and Finn count a minute, and another. The hall air is colder. On the other side of the door, something drags a fingernail down wood in a gesture that communicates we could be gentle forever. Maeve thinks of every time she has opened to a politeness she did not owe. She thinks of teaching Finn to say please and thank you and sorry—good spells that can be used, like all spells, in reverse if the wrong mouth pronounces them.

United States. Janelle’s phone glows with panicked texts from friends. The group chat that usually shares dog pictures has become a command center of Are you hearing it and I heard it and my neighbor opened. Someone sends a clip of a cul-de-sac with every porch light blowing out in sequence like breath on candles. Twelve, she thinks. But if each light is a knock, which house counted wrong first?

Japan. Kaito and his grandmother drink tea. When the twelfth knock passes, the air does not warm. It waits. Not hungry, exactly. Appraising. Kaito’s grandmother says, half listening to something that is not him, “When my mother was small, she said the mountain asked for children. Not by name. By number. The priest walked the village, door to door, and told them to count backward in their heads whenever the mountain asked.”

“Backward?” Kaito asks, grateful for arithmetic of any kind. He starts at twenty and works toward one, each number a bead.

Australia. Arun keys up. “Control, 312. Confirming multiple No Answer statuses. Do we have… any guidance?”

“Guidance is ‘Do Not Open,’” Control says, a breathy laugh in the words like a puncture. “We’ve been saying it for hours and I don’t know to who.”

A door up the street opens. Rosie says, “Don’t,” to the car, to the house, to midnight itself. A figure stands in the lit rectangle—too thin, too smooth, like a shadow cut from a magazine—then turns without stepping out and is folded back into the interior. The door remains open, a mouth that did not finish the sentence.

Chapter Six: The Taking

What the news will say the next day:

- Mass psychogenic illness.

- Coordinated vandalism, possibly AI-enhanced.

- Weather anomalies causing sensor failure.

What the news cannot say:

- The faces people saw weren’t faces, but the memory of a face when you close your eyes.

- The hands that reached were not made for grasping but for measuring.

- The laughter wasn’t glee. It was the relief of a lock picking the person who fits it exactly.

Here is how it happens, everywhere at once:

The first to open are the kindest. They open because a late child would be cold; because a person who knocks twelve times must need help; because rules are for cowards and children and tonight we are brave.

The second to open are the skeptics, because they’re angry at the superstition that made their coffee taste burned, their stomachs churn, their hands shake. They open to prove a point. The point dissolves, then they do.

The third to open are the lonely.

After midnight, houses that opened look no different from houses that did not—until you look longer. Then you see the small signatures: a sugar dust line on the threshold like a tide mark; a pumpkin rind on the sill, carefully hollowed; a coat on a peg that still remembers a shoulder. And a sense—as if the air has throat-cleared and then decided to hold the rest in—of a conversation cut off just as it learned how to say something true.

Maeve does not open. Janelle does not open. Kaito does not open. Arun does not open any for anyone.

But across their towns, many do.

And the number who do is the number the night asked for, not by name, but by math.

Chapter Seven: Morning, Exact and Thin (Friday, November 1, 2025)

Dawn is not merciful. It is only accurate.

Ireland. The Byrne door is still closed. Finn sleeps against Maeve’s hip on the couch, mouth open, breath catching in the small hitch children do when they have cried and then forgot and the body remembers for them. When she peels back the curtains, the lane looks freshly swept. The bowl on the wall is empty. The note is gone. In the field, crows do a quiet parliament.

At number thirteen, the plastic skeleton dangles. In the new house with the lanterns, the door is open. The word RILEYS hangs crooked. The hallway beyond has the ordinary catastrophe of a life—shoes that never find their pair, junk mail that will be interesting only when someone is dead and you read it all in a stubborn, aching awe.

Maeve stands on the step and calls, “Hello?” She does not cross. Her voice is the sound a coin makes when it drops into a well that never had water. She goes home and makes tea with her hands very careful, as if hot water could scald fate.

United States. Janelle’s live replay is a black box with a ten-minute runtime. The comments throb and split and mend. A local station runs a segment called Halloween Panic? with a smiling anchor who looks filmed from five inches further back than usual. The police scanner has gone from frantic to formal, words clipped down to bones. Janelle uploads a video titled I Didn’t Open and spends six minutes not crying while she says simple, un-profound things like: I decided not to and now I’m here. Her inbox fills with other people’s simple, un-profound relief: Me too.

Japan. Kaito’s grandmother opens the shrine doors and lights incense. She arranges persimmons with the care of a surgeon. She says, as if reporting weather, “Mr. Saito on the third floor didn’t answer his newspapers for once.” Kaito texts three friends; one replies, one doesn’t. He finds the poem again—someone reposted the removed thread in a screenshot. The comments have become a study circle. They translate and argue and correct. Twelve, they decide, is not a number in the poem so much as a limit, a fullness that demands an opening.

Australia. Arun finishes a twelve-hour that was only ten by the clock. At the depot, the talk is all sawdust humor and the iron filings of fear that hang in the air around men and women who see things they don’t have vocabulary for. Everyone counts coffee stirrers. Everyone counts something. In the locker room, he washes his hands a long time and thinks of the pumpkins and the boy and the door that opened like a yawn that never ended.

At noon, a joint statement comes down across nations in different languages that all say the same neutral thing: We are investigating disturbances and disappearances. They do not say Halloween. They do not say twelve. They do not say don’t open the door. They do not say we know what you know.

All over the world, survivors tell each other anyway.

Epilogue: The Whisper That Learns Your Name

Weeks pass. Winter leans in.

In Ballykillduff, the chalk under the hopscotch weathers, then is traced again by a hand that may belong to a child or to something that uses a child’s height to measure attention. The words are the same, the pressure deeper in the downstrokes: DON’T OPEN THE DOOR AFTER THE TWELFTH KNOCK.

In Columbus, Janelle edits footage and keeps the empty porch clip like one keeps a relic. She adds a note under her videos that is not a disclaimer but a blessing disguised as advice: You owe nothing to what knocks after twelve.

In Tokyo, Kaito’s grandmother teaches him to count backward in his head while stirring miso, while watering the spider plant, while waiting for buses that now come in quieter bunches. He finds that the numbers backward feel like a staircase he can walk down with someone else in his arms.

In Melbourne, Arun leaves a bowl on his own porch on November 30th, not because anything will knock but because he has learned that offerings can be a sort of hinge that lets fear swing open and pass through without demolishing the door.

Some nights, in the far corners of the places where people live, someone hears a practice tapping—a rehearsal of manners. It comes in sets. It is patient. It learns. It will ask again when the calendar brings it there, on October 31, 2026, as if numbers are doors and we are all houses.

Before then, one last thing:

If you hear it—the steady, courteous one-two-three like a promise—remember that the oldest stories are not about slaying monsters. They are about not inviting them over the threshold.

Promise yourself now, while the day is bright and the door is only wood:

Don’t open the door after the twelfth knock.

Teach your children a new magic trick: how to count backward and keep the number in their mouth. Teach your friends a spell: We can ignore what is polite when it is wrong. Leave sweets outside if it helps. Tape a note if it helps. Let the old bones of superstition wear modern clothes if it keeps them nimble.

And when the night comes, and it is kind, and it is patient, and it learns your name:

Do not open.

The kindness you owe the world is not the kindness you owe the dark.