Harry Rotter: The Girl Mystic and the Muddle

Harry Rotter

The Girl Mystic & the Muddle

Harry, Box, and the Business of Saving Everything

I wrote the following skit for a bit of fun, that’s all… But so many people, both adults and children, asked me to publish it, I felt obliged to do so. Who am I to say no to such desperate pleas?

Harry is a girl – and a mischievous one at that! Her real name is Harriet, but she insists that everyone calls her Harry. When Harry loses her Magical Marbles she enlists the help of her cousin, Box Privet, to retrieve them. At her behest, Box, who is a wizard with all things electronic, melds magic and electronics to make Harry an electro-magical wand . Pandemonium ensues…

Chapter One

No, Our Best China’s in There!

Mr and Mrs Privet, of number five Dorsley Drive, were anything but normal. Only a few weeks earlier they had been perfectly ordinary people — dull, even — but now they were as loopy as a basket of frogs from the local lunatic asylum.

On the outside, Mr Privet looked respectable enough: tall, bald, and thin as a broom handle. But beneath that polished exterior he was a bubbling stew of nervous tics, peculiar habits, and peptic ulcers — a man teetering permanently on the brink of a good shriek. His wife, Mrs Privet, was the opposite in shape but identical in madness: a large, round woman suffering from the dreadful affliction of hearing voices in her head. These voices came at all hours, shouting, whispering, singing hymns or demanding jam. Often she would sit bolt upright in bed and scream so loudly that her husband shook for half an hour afterward. It was, by any reasonable standard, a dreadful state of affairs.

Still, the Privets did their best to live as normally as possible. Each morning they rose, brewed tea, and pretended the previous night hadn’t happened. But hardly a day went by without one or the other succumbing to a fit of lunacy that would make ordinary folk throw up their hands and flee.

Before I continue, you must meet their son — Box Privet. (Yes, Box.)

He was the veritable apple of their eyes, though he shared his father’s unfortunate physique: tall, bony, and the colour of unpolished chalk. Schoolchildren teased him endlessly, but Box didn’t care. His heart belonged to a higher calling — electronics. In his small upstairs bedroom, armed with soldering iron, pliers, and tweezers, he spent hour after glorious hour bringing his strange inventions to life. He was happiest when surrounded by wires, resistors, and the faint smell of singed carpet. It was a lonely life, but he adored it.

As I said, the Privets had once been among the happiest families in their estate of mock-Elizabethan houses. But now they lived in fear for their very lives. Their cheerful, ordinary existence was in tatters — a shattered teapot of former contentment. And all because of one thing.

A secret.

A big one.

You see, the Privets had been hiding something — or rather, someone.

A girl.

Their niece.

Her name was Harry Rotter.

Well, officially she’d been baptised Harriet, but she refused to answer to anything but Harry. It suited her — bold, bossy, and thoroughly bad. She was the cruellest, nastiest child you could ever have the misfortune to meet. With her flowing golden hair and innocent, butter-wouldn’t-melt smile, she looked like an angel. But underneath she was all horns and spite. A bully through and through.

While she’d been safely locked away at her “special” boarding school — a gloomy institution called Hagswords — life for the Privets had been blissfully peaceful. But the moment she escaped from that high-security establishment and turned up at their door, everything changed.

“Excuse me, please,” said Harry sweetly when Mrs Privet opened the door. “I’m your only niece. Would you be so kind as to put me up for a few days?”

“It’s young Harriet, isn’t it?” said Mrs Privet, patting her nervously on the head. “Are you on a school break?”

Ignoring the question and resisting the urge to kick her aunt in the shins, Harry replied, “I prefer to be called Harry, if that’s all right with you.”

“Yes, yes, that’s fine,” said Mrs Privet, glancing up and down the empty road before ushering her niece inside. “Go into the front room, dear.”

A startled cat shot past Harry and vanished into the garden.

The room, Harry thought, looked exactly like Hagswords — far too much stained glass and carved oak for comfort.

“Sit down and make yourself comfortable,” said Mrs Privet. “I’ll fetch you some lemonade. You must be parched after your travelling. Then I’ll tell your uncle the… good news.”

Leaving Harry to examine the furniture, she opened a small door beneath the stairs leading down to the cellar, which served as Mr Privet’s private den. “Dear,” she called softly, “we have a visitor.”

“Who is it?” came the muffled reply from below.

“It’s your niece.”

BANG!

A hollow thud echoed up the stairwell, followed by groaning.

“Did you hear me, darling?”

More mumbling. Then, cautiously, “Are you sure it’s our niece — that niece?”

“Yes, dear. It’s young Harriet. I mean Harry. Harry Rotter.”

“Harriet or Harry? You should at least know the gender!”

“She’s a girl — she just likes the name Harry.”

“I don’t know if I know anything anymore,” muttered Mr Privet as he climbed the narrow steps. “Having to deal with your unusual relations…” He emerged puffing and red-faced. “Where is she, then?”

“I put her in the front room.”

“Our best china’s in there!” he shouted, and charged down the hallway like a man pursued by elephants. He burst into the room just in time to see Harry delicately inspecting one of their finest hand-painted cups.

“That’s an heirloom,” he stammered, eyeing her canvas shoulder bag. “Not worth a penny, mind you.”

“Not worth anything?” she asked, raising an eyebrow.

“No — worthless!”

“In that case, may I have it as a keepsake?”

Mr Privet nearly swallowed his tongue. “We… we can’t give it away,” he blurted. “We promised your grandmother, on her deathbed, that we’d always treasure it.”

Harry studied his sweating face for signs of deceit. “All right,” she said at last. “It was just a thought.” Then, looking around the room, she added, “Still, there must be something in all this rubbish you don’t want.”

“No, no, everything’s spoken for,” squeaked Mr Privet, clutching the mantelpiece as if it might defend him. “So tell me, uh, what brings you here?”

“I told your wife already,” said Harry cheerfully. “I’ll be staying for a few days.”

Mr Privet made a noise somewhere between a gasp and a whimper. At that moment Mrs Privet entered, carrying a tray with a tall glass of lemonade. She smiled at them both, quite unaware of the terror spreading through her husband’s veins.

“Everything all right?” she asked brightly.

Chapter Two

Meet the Son

Over the next few days, Harry settled into number five Dorsley Drive as if she’d lived there all her life. Unfortunately, the same could not be said for her relationship with Mr and Mrs Privet’s beloved son, Box.

From the very first moment she clapped eyes on his bespectacled, wisp-thin frame, Harry took an instant dislike to him. Box, for his part, returned the feeling with equal enthusiasm. But poor Box was no match for his cousin’s steely cunning and tireless determination to make his life a complete and utter misery.

This clash of personalities placed terrible strain upon the already-fragile household. Mr and Mrs Privet prided themselves on being open-minded, modern parents — tolerant of “challenging behaviour” and fond of quoting child-rearing books. They tried their best to overlook Harry’s monstrous acts of mischief, but each day brought new horrors.

She tripped Box down the stairs.

She salted his porridge.

She removed all the fuses from his beloved gadgets and gizmos.

And that was only Tuesday.

In time, Box took to avoiding Harry altogether. If he saw her walking toward him in the street, he’d dash into the nearest shop and hide among the tins of custard. If there were no shops nearby, he’d sprint up the nearest garden path and hammer frantically on the door until someone took pity on him.

At home, he became a recluse. He spent nearly all his waking hours in his bedroom, where he installed bolts, chains, padlocks, and even a homemade alarm system. Each night the house echoed with the sound of bang, bang, bang as Box secured himself inside his fortress before diving under the covers.

Harry, meanwhile, required no such defences. Who would dare to enter her room without permission? She had the run of the house and made full use of it. Yet she, too, began spending more and more time in her room — though for far darker reasons than her trembling cousin.

Harry had plans.

It had been several days since her escape from Hagswords, the boarding school for mysticism and magic, and she knew her freedom wouldn’t last forever. She had left behind a cunning decoy — a mannequin, enchanted to resemble her — but even the cleverest trick could not last indefinitely. Sooner or later, the teachers would realise their mistake and start searching.

For a time she considered casting a spell of concealment over number five Dorsley Drive, but with all the daily comings and goings, she decided it would be pointless. The only way to be truly safe, she reasoned, would be to prevent anyone from entering or leaving the house altogether.

She smiled to herself in the dim lamplight.

“Hmm,” she murmured. “That might not be such a bad idea…”

Meanwhile, somewhere across the landing — bang, bang, bang! — Box was locking himself in again for the night.

Later, Harry lay in bed reading by candlelight. The book she held was old and cracked, stolen from the forbidden section of the Hagswords library. Its pages whispered faintly as she turned them.

“They’re so stupid at that school,” she hissed under her breath. “They call it a school for mysticism and magic — more like a school for cowardice and compromise! Too frightened to offend the Muddles, too soft to wield real power.” Her eyes gleamed in the candlelight. “Well, I’ll show them. I’ll show everyone — even the Muddles — what I can do.”

She read long into the night.

Next morning, Box leapt from bed at dawn, determined to complete his morning routine before his cousin awoke. He performed his ablutions with military precision, swallowed his breakfast in record time, and planned to slip out to school unseen.

Quietly he unbolted his bedroom door, inch by inch. The final latch clicked. He peeked into the hall.

“Hello,” said a voice less than three inches from his nose.

Box froze. Harry stood there smiling sweetly, her eyes as cold as marbles.

“Did you sleep well?” she asked.

“I—I—” Box stammered, incapable of speech. Then he slammed the door shut.

Knock knock.

“Box, it’s me, Harry,” she cooed through the wood. “Are you coming out today?”

Box said nothing. He was already considering whether it might be safer to climb out the window and take his chances with gravity.

“Is that you, Box?” called Mrs Privet from the bottom of the stairs.

“No,” Harry answered cheerfully. “It’s me.”

“Oh! Up early, dear?” said Mrs Privet, startled. She bustled back to the kitchen to begin the morning fry-up Harry demanded each day. Then she poked her head out again. “Would you like to go somewhere nice today? The zoo, perhaps?”

Harry paused. She had lost all track of time — it was Saturday already. Her mind whirred like clockwork. “Yes,” she said at last. “I’d love to. But only if Box comes too.”

At the breakfast table, Mr Privet lowered his newspaper and stared bleakly at his wife.

“Now,” he said quietly, “why on earth did you have to go and say that?”

Chapter Three

A Visit to the Zoo

It was a grand day for a drive — the first time in her entire life that Harry Rotter had actually been invited on a family outing. Mr Privet was at the wheel, of course, driving slowly. He always drove slowly, insisting that cars lasted longer if treated gently, as though they might one day thank him for it.

Harry stared dreamily out of the window, enjoying the novelty of it all: the hum of the engine, the soft chatter of her aunt, the feeling — just for a moment — of belonging. She almost allowed herself to think kindly of people, even the Muddles. But only for a moment. Then she came to her senses. Sentimentality, she reminded herself, was a disease.

Box had been dragged along under protest. His parents had refused to let him stay at home “playing with his gadgets” while they suffered through the day. Misery, in their household, was a family affair.

When they reached the zoo, Mr Privet parked with exaggerated care. He claimed tyres lasted years longer if you parked properly — though no one else had ever tested the theory. Together, the not-so-happy family approached the entrance.

“Two adults and two children, please,” said Mrs Privet, handing over a five-pound note to the spotty attendant.

“Isn’t she paying for herself?” whispered Mr Privet. “You said her side of the family was loaded.”

“Hush,” snapped Mrs Privet, forcing a smile while praying that Harry hadn’t heard.

It was a fine Saturday, yet the zoo was surprisingly quiet, leaving the Privets and Harry to roam almost alone among the enclosures.

“Where are you going?” asked Mrs Privet, catching her son trying to slink away.

“I was just—” he began.

“You’ll stay right here with us,” she said firmly. “Harry especially asked for you to come.”

“I know,” muttered Box. “That’s what worries me.”

From crocodiles to buffalo, from elephants to chimpanzees, from parrots to moorhens and everything in between, they trudged through the zoo’s paths. But Box couldn’t shake the feeling that his cousin was planning something — something horrid. Unfortunately, he was absolutely right.

They were in the reptile house when Harry made her move.

Box was standing by a glass enclosure, peering at a particularly large snake, when he heard the faint click of a lock behind him.

“What are you doing?” he cried, seeing Harry swing open the heavy glass door — a door that had been locked with both a bolt and a padlock.

“You’ll find out soon enough,” she said sweetly, giving him a push inside and slamming the door shut.

“Let me out!” Box shouted, pounding the glass.

The snake, delighted by the unexpected company, began to slither toward him.

“LET ME OUT!” Box yelled again, hammering wildly on the partition.

At the far end of the room, Mr and Mrs Privet were admiring an albino tree snake, blissfully unaware of their beloved son’s impending doom.

“Well?” said Harry, folding her arms, watching Box with cool amusement.

“Well what?” he screeched, his eyes fixed on the approaching reptile.

“Are you going to help me?”

“Help you with what?” he wailed.

“All in good time,” she said, smirking. The power was delicious — like eating ice cream on a sunny day.

The snake was inches away now, tasting the air with its forked tongue. Box screamed, “Okay! OKAY! I’ll help you! Just get me out of here!”

Satisfied, Harry drew her wand. “Open Ses Me,” she said, waving it casually.

With a pop, Box found himself standing safely on the outside of the glass, shaking violently. The snake’s jaws snapped shut on empty air.

“H-how did you do that?” he gasped.

“Do what?” said Harry, slipping the wand back into her pocket.

“That thing! The… the thingamajig!”

Ignoring him, she said, “Come on. I need your help.”

“Me?”

“Yes, you, genius. Unless you’d rather go back in there with your new friend.”

Having no desire to test her threat, Box followed her meekly out of the reptile house.

“Here, eat this,” said Harry a little later, handing him an ice cream cone she’d bought at a nearby kiosk.

Box eyed it suspiciously. “Is it… safe?”

“It’s ice cream,” said Harry. “If you’re that worried, we can swap.”

“No, no, it’s fine,” he said quickly, taking a tentative lick. “Thanks.”

That made twice in one day that Harry had shown him a scrap of kindness. Box was confused — and, if truth be told, slightly hopeful.

They wandered toward a quieter corner of the zoo, where the paths were shaded by tall trees and the air smelled of damp leaves. Then Harry spoke.

“Box,” she began, “you’re good with electrical things, aren’t you?”

He nodded cautiously.

“Good. I, on the other hand, have absolutely no knowledge of such matters — nor the slightest interest.”

He nodded again, unsure what to say.

“I want you to make me something. Something electrical.”

Now she had his attention. “What do you want me to make?”

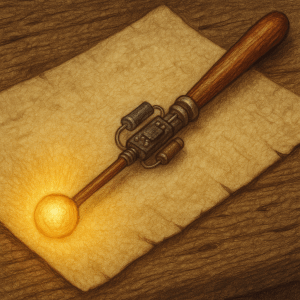

Harry hesitated, weighing her words. Then she reached into her pocket and withdrew the wand.

Box’s eyes widened. “A wand! I knew it! Just like the ones Dad sometimes talks about!”

“Tell everyone, why don’t you?” hissed Harry. “Honestly, you Muddles are hopeless.”

“Sorry,” he said meekly. Then, unable to resist, he asked, “Can I touch it?”

“No, you cannot.”

Box looked crushed.

“You can touch it later,” she said, relenting slightly. “For now, just look.”

Box gazed at the polished brown wood in awe. “I can hardly believe it,” he whispered. “A real magical wand…”

“Now that you’ve had your look,” said Harry briskly, tucking it away again, “can we return to the matter at hand?”

“Yes, yes, please go on,” he said eagerly.

Harry explained her idea carefully — enough for him to grasp the practical parts, but not enough for him to understand her real intentions.

“So you see, Box,” she concluded, “I want you to build a wand that combines the magic of mine with the… technological wisdom of the Muddles.” She grimaced at the word. “I hate saying that. ‘Wisdom’ and ‘Muddle’ in the same sentence.”

Box frowned, deep in thought. Technically, it was possible — just barely. But how could he merge the electrical and the magical? He chewed his lip, considering.

At last he said, slowly, “I think I can do it.”

Harry smiled. For the first time, it was genuine — and, to Box’s surprise, rather beautiful.

“It won’t be easy,” he added hastily. “Not by any stretch of the imagination—”

“But you can do it?” she interrupted, still smiling.

“Yes, but—”

“That’s all that matters.” And, quite out of character, Harry leaned forward and kissed him on the cheek.

Box turned bright red. “I—I’d better go find Mum and Dad,” he mumbled.

“Of course,” said Harry sweetly. “You do that.”

As he scurried away, Harry watched him go, smiling to herself.

The plan, she thought, was working perfectly.

Chapter Four

Secrecy, at Any Cost

Next morning, Harry tapped softly on Box’s bedroom door and whispered, “Box, are you awake?”

A muffled voice replied, “Hmm… what is it?”

“I said, are you awake?”

“What time is it?” Box grumbled, rubbing his eyes.

“Half past six.”

“Half past—six?” he croaked, sitting bolt upright. “You’re joking.”

He reached for his glasses and peered at his watch. To his horror, it really was six thirty.

“Yes,” said Harry, a little louder now, “I’m sure of it. Now are you getting up, or do I have to send for that snake?”

That did the trick. Box leapt from bed, dragged on his dressing gown and slippers, and began unbolting his door. Bang, bang, bang went the bolts as they slid back into their daytime position. The door creaked open to reveal his bleary, frightened face.

“What’s the problem?” he yawned.

“There’s no problem,” said Harry brightly. “We have work to do.”

“But it’s Sunday,” he protested. “I always have a lie-in on Sundays.”

“Not anymore, you don’t,” said Harry. “Not until the job’s done.”

“But we don’t even have the supplies,” he tried again. “The electrical shop’s closed till tomorrow!”

“Then we’ll plan today,” said Harry firmly. “Now stop whining.”

He hesitated. “I suppose you might really have that snake somewhere, mightn’t you?”

“You never know,” she said sweetly.

That settled it. “All right,” he sighed. “But I’m having breakfast first.”

“Good idea. I’ll see you downstairs.”

And with that, she thundered down the stairs two at a time.

Box scratched his head. “What have I done,” he muttered, “to deserve a cousin like her?”

When he reached the kitchen, Harry was waiting beside a plate.

“There you are,” she said, pointing.

Box peered at it. “What’s that supposed to be?”

“A fry-up, of course,” she said, pushing it toward him. “Eat up. It’ll keep you going.”

It smelled wonderful, which was peculiar, because he hadn’t heard any cooking. But he knew better than to ask questions that might be deemed “Muddlish.”

“And keep the noise down,” Harry warned. “We don’t want to wake the old cronies.”

“The… old cronies?” he asked. Then, laughing, “Oh — you mean Mum and Dad. Funny, I used to call them that once.”

“You did?” she said, smiling faintly.

“Yep. It’s a funny old world, isn’t it?”

“It sure is,” Harry muttered, wondering how many other silly Muddles lived on Dorsley Drive.

When he’d finished his surprisingly tasty breakfast, Box asked, “So, what’s first on the agenda?”

Harry leaned close. “Secrecy,” she whispered.

“Pardon?”

“I said secrecy!” she repeated. “You must keep everything we do a secret from your parents!”

Box swallowed hard. “Everything?”

He’d never kept a secret from them in his life.

“Yes, everything,” she insisted. “And not just them — everyone you know. Have I made myself clear?”

“Yes, I suppose so,” he said nervously, “but it won’t be easy—”

“Nothing worth doing ever is,” said Harry briskly, and marched out the door.

“Where are we going?” Box called, following her down the garden path.

“Somewhere private.”

Harry led him to the park. It was early enough that the gates were still locked, so she simply climbed over. Box followed, tearing his dressing gown in the process.

“Sit,” she ordered, choosing a damp patch of grass.

“Here? It’s wet—”

“SIT.”

He sat.

From her pocket she produced a small notepad and pen she’d just bought at the newsagent. For the next ten minutes she scribbled furiously, muttering to herself as she wrote. Bored, Box watched sparrows hop closer, hoping for crumbs that never came.

At last Harry tore out a couple of pages and handed them over. “Here. Read that and tell me what you think.”

Box scanned the two pages. Then, without a word, he held out his hand for the pen. Harry gave it to him, curious.

He began writing. Quickly. Intensely. Line after line, page after page. Occasionally he glanced at Harry’s scribbles, then went back to his own. Fifteen pages later, he stopped — exhausted but triumphant — and added two more with a list of materials.

“There,” he said, handing it back. “Now you take a look.”

Harry flipped through the pages, frowning at the indecipherable sketches and numbers. “It might as well be double Dutch,” she said, “but I trust you, cousin. Let’s get started.”

Box grinned — he loved a challenge. Then his grin faded. “Uh-oh.”

“What’s wrong?” asked Harry.

“Money,” he said. “That lot will cost a fortune.”

“Leave money to me,” said Harry coolly. “You just focus on the work.”

Next morning, Monday, they set off for town.

“I can’t imagine what’s got into those two,” said Mrs Privet, pulling back the curtain as she watched them board the bus. “One day they’re mortal enemies, the next they’re best friends.”

At the kitchen table, Mr Privet peered into the remains of his son’s breakfast. “Any more where that came from?” he asked hopefully.

Town was busy — far too busy for Harry’s liking. “There are so many Muddles here,” she muttered darkly, dodging a youth on a motor scooter. “Which way?”

“This way,” said Box, pointing up a steep hill.

“Why couldn’t they build the shop at the bottom?” she grumbled, panting as they climbed. Then, realising the answer, she added, “Ah yes — Muddles.”

At the top stood a dusty old electrical supplier. The bell above the door jingled as they entered, and an elderly man behind the counter peered at them over the rim of grimy spectacles.

“Can I help you?” he asked.

“I certainly hope so,” said Harry.

Box handed over their long list.

The man squinted. “Hmm… unusual mixture of items. What did you say you were making?”

“We didn’t,” snapped Harry.

“We’re making a transmitter,” Box blurted quickly. “For school.”

“A transmitter, eh?” said the old man, pushing his glasses up onto his forehead. Harry wondered how he’d managed to see through them at all.

“You really need a licence for that,” he warned.

“We know,” said Box smoothly, “but it’s just an experiment — temporary.”

“Hmm.” The man fetched a battered order book and began writing. “All right then.”

He disappeared into the back of the shop. For twenty minutes there was silence, broken only by faint thumps and the occasional cough. Box studied the faded posters on the wall. Harry stared out the window, bored stiff.

At last the man returned, puffing and panting, carrying two cardboard boxes bulging with electrical parts. He plonked them on the counter. A cloud of dust rose. Harry coughed.

“There you are,” he said proudly. “Everything you wanted. Some of it’s been sitting back there for years — thought I’d never sell the stuff! Just goes to show, doesn’t it?”

“Thanks,” said Box. “How much?”

“Ah, yes.” The man rummaged in a box. “Here we are.” He handed over the bill.

Box turned pale. “We can’t possibly—”

“I’ll take that,” said Harry, snatching it. She glanced at the total without flinching, opened her shoulder bag, and pulled out a small purse.

“There you are,” she said, placing three golden coins on the counter. “Keep the change.”

The man blinked. “Are you sure? These are worth far more than—”

But Harry was already at the door. “Come on, cousin,” she said, gesturing for Box to carry the boxes.

He staggered under their weight as they left the shop. “Where did you get those coins?” he asked breathlessly.

Harry smiled a secret smile. “Let’s just say,” she murmured, “the past can be very… profitable.”

Chapter Five

The Hybrid New Wand

It was decided (by Harry) that the new hybrid wand would be assembled in Box’s bedroom, which conveniently contained a workbench and an immodest quantity of tools. Harry might have worried about Laurel and Holly discovering what they were up to, if not for the small fortress Box had made of his door: bolts, locks, chains, and a notice that said KEEP OUT in very firm pencil. Once inside, clack went the locks; the Privets hadn’t a hope of seeing a thing.

“What can they be doing up there?” Holly wondered one evening, listening to the clinks and zzzts from overhead.

“You told me they were making a radio,” Laurel said, turning a page of his newspaper.

“Yes, I did.”

“I see wholesale fruit and veg are up again,” he grumbled, giving the children no further thought whatsoever.

Holly said nothing, but she listened hard, the way mothers do when instinct and dread are arm-in-arm.

“Laurel, did you hear me?” she tried. “Prices up again!”

“That’s nice, dear. I’m thrilled,” she replied to herself, and Laurel turned another page to an article about owls dive-bombing children in the park. “World’s gone barking mad,” he muttered.

For a week, Harry and Box scarcely left that cramped room. Box, at the bench, soldering and sketching; Harry, wand in hand, explaining, translating, and generally bullying the laws of nature into cooperation. The task was to transfer her wand’s powers into a new electro-magical chassis. Sparks flew. Smoke curled. Odd lights pulsed. Once, the wallpaper sang.

Near the end, something unexpected happened. The old wand, which Box had assured her would neatly dwindle to nothing, began to shrink… then stopped. Matchstick-sized, it refused to vanish, no matter what coaxing, cursing, or cleverness they applied.

“It’s done,” Box panted at last, setting down a humming, rather handsome steel rod. “Mostly.”

Harry eyed the matchstick. “Mostly,” she agreed.

They crept downstairs, soot-smudged and triumphant.

“The only thing left is to test it,” Harry whispered.

“Now?” Box begged.

“Later,” said Harry. “When no one’s here.”

“It’s lovely to see you both out of that stuffy room,” Holly said as they entered the kitchen. “How’s the radio coming along?”

“The radio?” Box blinked.

“All finished,” Harry said quickly, elbowing him in the ribs hard enough to water his eyes. “Any lemonade?”

Holly poured two glasses. “Into the dining room with you. Dinner’s nearly ready.” She called through, “Laurel, Harry and Box have finished their radio!”

“About time,” came the reply. “With the hours they’ve put in, they could have made a bomb.”

Heavy footsteps mounted the stairs.

“Dinner is almost ready!” Holly warned.

“Just going for a piddle,” Laurel called back. “Down in a jiff.”

He did go for a piddle. He also went to peep at the brand-new “radio”.

“Here we are,” Holly said to the children, setting down two heroic slabs of shepherd’s pie. “Your favourite, Box.”

Famished, Box fell on his plate like a happy wolf. Harry prodded hers distractedly, eyes on the ceiling. Something was wrong.

“Don’t you like it, Harry?” Holly asked.

Box nudged Harry this time.

“Hmm? What?”

“Your dinner, dear.”

“Delicious,” Harry said, calmly holding up a spotless plate.

Holly’s jaw dropped. “How did you—?”

“Upstairs,” Harry hissed to Box. “I think we left the door unlocked.”

“Can’t I finish—?”

“You have.”

“I haven’t!” he protested. “I’ve barely—”

“Look at your plate, dummy.”

Box stared. His plate was shiningly clean.

“But I didn’t eat it,” he moaned. “I’m still starving!”

“Have you forgotten your father?” Harry snapped. “Muddles and their food.”

On the landing, Laurel had already spotted the bedroom door ajar. He eased it open and peered in. No radio. Just the bench—and a peculiar steel rod lying there as innocently as a butter knife.

He slipped inside on tiptoe. The floorboard squeaked. He froze. No one came. He went on.

He picked up the rod and gave it a speculative wave. “Hmm. Doesn’t look like a radio,” he murmured. He noticed little buttons at one end. “On/off? Stations?” He pressed the first. A click. Nothing obvious.

“I wish I knew what was going on around here,” Laurel sighed—at which moment, unhelpfully, he did. His mind filled at once with a blistering, perfect understanding of what the children had been building, and for how long, and why the wallpaper had been singing the previous afternoon. He laughed nervously. “Pull yourself together, Laurel, or it’s the loony bin for you.”

Feeling emboldened, he flourished the rod like a conductor’s baton. Music burst into the room. He stopped. The music stopped.

“Aha,” he said. “Radio after all. Just needed to warm up.”

He pressed the second button.

A gout of flame roared from the wand, searing the wallpaper into instant toast.

“No, no!” Laurel cried, swivelling wildly. The wardrobe caught next.

From below came a cry and the thunder of feet. Harry and Box flew up the stairs. The bedroom door was flung open, and a river of heat blasted into the landing.

“Well,” Harry said, almost pleased, “at least we know it works.”

“My room!” Box howled, unable to see for the smoke.

Holly arrived and burst into tears. “Laurel! What have you done? Laurel!”

Harry hesitated for the first time in her life, shocked by the sheer Muddleness of it all.

Box did not. “Point it out the window!” he shouted.

“What?” Laurel coughed.

“Out. The. Window!”

“But it’s shut!”

“Doesn’t matter—DO IT!”

Laurel aimed. The flames shattered the glass into a million glittering pieces that rained onto the path below.

Box and Harry plunged through the doorway. Laurel, black with soot, still gripped the wand, shooting fire into the sky like a very anxious dragon.

“Help!” he cried. “It’s gone berserk! I only wanted to change the station!”

“Harry will stop it,” Box said stoutly. “Your department, cousin.”

“It does seem a pity,” Harry mused, “to waste such a splendid flame.”

“HARRY!”

“Oh, very well.” She muttered words that did not belong in a suburban house and flicked two neat gestures. The fire vanished with a hiss.

Laurel, trembling, set the ‘radio’ on the bench. A little ember licked at a scrap of paper; he licked his fingers and pinched it out. “I only wanted to change the station,” he murmured. “Just the rotten station.”

“Holly?” he called weakly.

“I’m here,” she said, stepping into the ruin. She saw the scorched walls, the charred wardrobe, the demolished window—then she saw her husband, black as a chimney sweep—and burst into fresh tears.

“It’s all right,” Laurel said, guiding her away. “It’s not that bad. Wrong station, that’s all. Silly mistake.”

They tottered to their room and closed the door on the memory.

“Phew,” Harry said, winking at Box. “That was close.”

“Close?” Box spluttered. “We could have been burned to a crisp!”

“Might have,” Harry said, stung by his lack of faith. “But weren’t.”

With a few more murmured words and the newly tested wand, she put everything back as it had been: wallpaper un-toasted, wardrobe un-charred, window un-shattered, right down to a cobweb in the ceiling corner.

By morning there was nothing to suggest catastrophe at all. Laurel and Holly decided, quietly and with great relief, that it had been a very bad dream. After all, how could it be otherwise, when there wasn’t the slightest sign of damage anywhere?

Chapter Six

Are You Coming?

A week to the day, in the small hours before dawn, Box woke to a soft tap at his bedroom door.

“Who’s there?” he whispered, fumbling for his glasses.

“It’s me. Harry.”

“What do you want?”

“I want to talk.”

“Can’t it wait till morning?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

Silence.

“I said, why not?”

“Let me in.”

By now Box knew that when Harry had something on her mind, resistance only made it worse. He climbed out of his warm bed, unbolted the door—bang, bang, bang—and let her in, then dove back under the covers.

“Well?” he yawned. “What’s so urgent it couldn’t wait?”

Uncharacteristically, Harry searched for the right words. “I’m leaving.”

“Leaving? When?”

“Today.” A beat. “And I wanted to ask… if you’d consider coming with me.”

“Me? Why? Where are you going?”

“To Hagswords.”

“Hagswords?” He sat bolt upright. “You escaped from there. I never thought you’d go back.”

“It’s only a matter of time before they find me,” she said carefully. “If I take the initiative—if I go first—I might still have a chance to find it.”

“To find what?”

“Something I left behind.”

“And you must go back for it?”

“Yes.”

“It’s that important?”

“Yes.”

“What is it?”

“I can’t tell you.”

“Clue?”

“No.”

Silence swelled. Mr and Mrs Privet’s snoring from the next room could be plainly heard, like two contented hippos.

For all that he knew her selfish streak and secret plans, Box had grown used to Harry in a peculiar way. And he very much wanted to see what the electro-magical wand could really do.

“All right,” he said at last. “I’ll come. But I’m not doing anything illegal. Clear?”

Harry nodded, smiling. For the first time in her life, she was oddly happy to have someone—yes, even a tall, wisp-thin Muddle like Box.

“Can’t we say goodbye?” Box asked a few minutes later, one leg already out the window and onto the trellis that held the white, flowering rambling rose.

“No. I told you—the less your parents know, the safer they’ll be. Now hurry. I’ve a bad feeling…”

Halfway down, he pricked his finger on a thorn and sucked it. “A bad feeling? What sort of bad feeling?”

“I can’t explain,” she said, following him. “Something I learned at Hagswords.” She gave a dry little laugh. “At least I learned one useful thing.” Then, impatient: “Go on—what’s the hold-up?”

Box pointed east, hands shaking. “Carpets.”

High in the brightening sky, two shapes approached fast. They looked exactly like flying carpets.

“Drat,” Harry hissed. “They’ve found me.”

They dropped the last few feet, rolling into the shrubbery: Harry under the vast leaves of the Gunnera, Box under the equally enormous rhubarb (his father maintained rhubarb was a criminally undervalued flowering plant with magnificent white blooms, no matter what the neighbours said). From their leafy hideouts they watched the carpets and their cross-legged riders sweep overhead.

“They didn’t stop,” Box whispered.

Harry wriggled over, joining him beneath the rhubarb canopy. “That means they haven’t fixed my position. We still have a chance.” She looked at him, strangely gentle. “You should go back in. It’s me they’re after. Go.”

“Oh no you don’t,” Box said fiercely. “We’re in this together.”

“They could return any moment.”

“It doesn’t matter,” he insisted. “Is there anything we can do to get away?”

Harry unfastened her shoulder bag and rummaged.

“Use the new wand?” Box breathed.

“No. That would be like ringing a bell.” She kept searching. “Ah.” She pulled out a bulky bundle tied with brown string.

“How did you get that in your bag?” Box blurted.

Harry ignored him and undid the string. She shook the bundle out onto the grass. It was a carpet—very old, threadbare in places, and exquisitely patterned.

Box gaped. “Is that… really—? No, it can’t be.”

Harry smiled.

“It is?”

She nodded.

“A real flying carpet?”

The carpet smelled agreeably musty.

“Let’s go,” Box urged.

Harry didn’t move. She watched the sky. Timing would be everything.

Alas, plans seldom obey their makers. Before they could launch, the two carpets returned and began circling.

“They’re on to us,” Harry murmured.

“You must’ve really annoyed them back at school,” Box said. “All this just for you.”

Harry ignored that.

One carpet, with a bearded rider, kept circling as lookout; the other, bearing two robed men, drifted down and landed neatly under the horse chestnut tree. The men strode across the lawn toward the house.

“What are they doing?” Box whispered.

Harry said nothing.

“Where are they going?”

“Inside.”

“You mean—to Mum and Dad?”

“I’m afraid so.”

Almost in tears, he whispered, “What do they want with them?”

“They’re in there. That’s why.”

“But they don’t know anything!”

“Shh—they’ll hear you.”

Inside, Laurel and Holly slept on, blissfully unaware. That ended when someone kicked in their back door.

“Did you hear something, Laurel?” Holly said, sitting up, ears cocked.

“No. Go to sleep,” Laurel mumbled.

Holly lay back, trusting him. Clump, clump, clump. Heavy footsteps crossed the polished floorboards. Something crashed—something television-sized.

“Laurel,” she hissed, jabbing him again, “there’s someone downstairs!”

“I told you—no one there. Sleep.”

“LAUREL. GET. UP!”

He got up. Slippers, dressing gown, door opened—then slammed again. A bearded man in long robes stood outside, wielding a very small stick in a very threatening way.

“I say,” Laurel protested, eyeing the stick. “That’s not cricket.”

The man shoved Laurel back into the room, where he stumbled onto the bed and his wife.

“My,” Holly said, eyes brightening, “and it’s not even Sunday.”

“Stop that,” Laurel said sternly. “We have a problem.”

Holly opened her eyes properly, saw the bearded man, and screamed.

Outside, Box flinched. “They’ve got Mum and Dad! I’m going up—”

The circling carpet dipped, turning toward them.

“Now see what you’ve done,” Harry hissed.

“What I’ve done?”

There were no further screams; the intruders had gagged the Privets and tied them fast. Laurel, who had long since decided wands were terrible for one’s health, glowered helplessly at the little stick and loathed it with all his heart.

Harry tracked the descending carpet. “We’ve a minute at best. We go now.” She dragged the carpet out from under the rhubarb onto open lawn.

“We can’t just leave them,” Box said, frantic. “We must do something!”

Harry considered. “All right. I suppose we can spare a flick—since we’re leaving.” The lookout carpet was dropping fast.

“Use it then! Use it!”

“On you get,” she said, seating herself cross-legged. It was a tight squeeze. Box’s long legs had to fold like deckchairs.

“Now what?” he whispered. The house was ominously quiet.

“Just a few words,” Harry breathed.

“Say them!”

She drew the new electro-magical wand, gave it a small left-right-left flourish, and murmured, “Loosen up the cords that tie; free those souls from binds so tight.”

“That’s it?” Box said, deflated. “No flames, floods, or pestilence? Just… words?”

“It’s best that way,” said Harry primly. Then, with another flick: “Up, up, and away.”

The threadbare carpet quivered, trembled, juddered—and shot forward straight at the smashed back door.

“What are you doing?” Box yelled.

“Hold on! It’s been a while.”

“How long is a while?”

“Like… never?” she admitted.

Above, the lookout carpet peeled off in pursuit.

They blasted through the caved-in doorway, skimmed the kitchen at treetop speed, tore down the hallway, and burst through the front door, reducing it to toothpicks.

“Back inside!” Box cried, seeing the pursuer gaining.

Harry yanked the carpet into a hair-pin turn. They whipped through the debris-strewn sitting room, the pursuer hard on their tail, its rider—now brandishing a sword—red with fury.

Harry veered right into the front room. This, tragically, was the sanctuary of Holly’s hand-painted, fine bone china. The two carpets swooped and wheeled in a cramped, porcelain-lined dogfight, causing more destruction in seconds than the intruders had achieved in minutes. With growing confidence, Harry slotted them through the doorway again just as their pursuer smacked squarely into the display cabinet, annihilating the china and, mercifully, knocking himself out.

“Upstairs!” Harry cried, and the carpet surged up. Box clutched the fringe and whimpered.

They hit the landing, smashed through Laurel and Holly’s bedroom door, and cannoned neatly into the two robed men inside, knocking them senseless.

“Dad! Are you all right?” Box shouted, seeing Laurel already spitting out a gag and fumbling at his cords.

Giggling, Laurel said, “Hmm—another of Harry’s radios exploding, is it? Dangerous things, radios. Hee, hee.”

“What’s wrong with him?” Box whispered.

“Shock,” Harry said briskly. “Seen it before. Hagswords.”

Laurel tottered to Holly and worked at her knots. “Come on, dear,” he said dreamily. “I think the vicar’s coming to tea, and you promised him your special scones. Hee, hee.”

Holly said nothing. She sat on the floor, eyes glazed, listening to the voices she’d lived with for years. They were very soothing now. Everything would be all right—so long as she kept listening.

Chapter Seven

A Train to Catch

Box didn’t like leaving his parents, but he knew that if they were ever to return to anything resembling their quiet old life, he had to go. Harry had already “dispatched” the robed intruders to a place where, she claimed, they’d be safely contained until everything was sorted. Box decided—for the sake of his nerves as much as theirs—not to ask where “there” was.

High above the clouds, the moth-eaten carpet skimmed along at a glorious clip. Box looked back and watched his house shrink to a dot, regret nibbling at him. If only Harry had never escaped from that school…

For an hour they said nothing. The carpet hummed. Thoughts clattered. Somewhere inside Harry, a plan clicked forward another notch.

When the carpet began to slow, Box tapped Harry’s shoulder. “What’s happening?”

She didn’t answer. Jaw set, eyes forward, she sat cross-legged like a small, determined statue.

The carpet dipped; the world swelled. Trees grew into forests; roads braided into rivers of light.

“Careful,” Harry murmured, “or you’ll fall off.”

“Are we landing?”

She nodded—just as London rose beneath them like an enormous clockwork map.

“Why here?” Box spluttered. “Why the middle of—?”

Harry pointed. “Euston.”

“A railway station?” he squinted.

“We have a train to catch.”

They slipped through a discreet opening in the roof and kissed down onto the concourse as if this sort of thing happened at Euston every day. No one looked twice.

Harry folded the carpet briskly and slid it into her bag. Box blinked at the bustle and their… unconventional arrival. “Why stop? Why not fly all the way? And where are you going?”

She strode off without replying.

“Well?” he tried again, trotting after her.

Harry wheeled. “Must I narrate every last detail?” That settled the matter. Box buttoned his questions and followed.

Under the great clock she veered right to a ticket window. From her purse she produced another gold coin and slid it across. “Two platform tickets, please. Keep the change.”

The clerk stared, slipped the coin into a pocket with priestly reverence, and paid for their tickets from her own purse. “There you are. Have a nice day.”

“Platform thirteen,” Harry said, already moving. At the barrier, a kindly old attendant clipped their pasteboard and grinned. “What have we here—two train spotters?”

“Something like that,” said Harry.

“The board says ‘Argyle,’” Box noted. “And we’ve only got platform tickets.”

Harry was fifty paces ahead. He hurried after her, calling “Harry!”—but she was at the far end now, still marching.

“HARRY, WHAT ARE YOU—” He broke off. She stepped clean off the end of the platform and vanished.

Box skidded to the edge, heart thundering. Nothing. Just sooty air and the far-off tick of iron and time.

“Did you see her?” he begged an ancient porter shuffling past.

“See who?” said the man, cucumber-cool.

“A girl—Harry.”

“Funny name for a girl,” the porter observed, and drifted on. “I sees nuthin’. I keeps to meself. Don’t get into trouble that way.”

Box paced, brain in knots. In the end, with no better idea, he decided to do as Harry had done. He took a breath, clenched every available muscle, and stepped off.

He did not fall. The world rolled like a clock hand. He swivelled neatly and found himself standing—upright and perfectly un-upside-down—on a second platform directly beneath the first, where everything agreed with itself and thus felt normal.

Up above, the porter blinked and muttered, “Saw nuthin’. Nothin’ at all,” and went on not seeing it.

“You took your time,” Harry said, hands on hips, displeasure doing star jumps.

“I—” Box began.

“No ifs or buts. We have a train to catch.”

Only then did he see her: a gleaming blue locomotive sitting in full, glorious steam. His heart stopped. “That’s Mallard,” he whispered. “Fastest steam engine ever built.”

Harry was already at the second carriage. “Are you moving, or shall I go without you?”

“Coming!” He ran a fingertip along the streamlined casing, almost reverent, then clambered aboard.

Inside was a film set come to life—panelled walls, stained-glass screens, cut mirrors etched like frost. “Wow,” Box breathed.

“What are you doing?” Harry said crisply as he hovered over a Queen Anne chair.

“Er—coming.” She led him to seats half-hidden by a stained-glass topper. He sank into a deep, upholstered armchair and sighed.

“If someone had told me a few weeks ago that I’d be here,” he said, “on a train headed by Mallard, in—where are we, anyway?—I’d have called them barking. But here I am. And I’m not barking. Am I?”

“We’re in England,” Harry said.

“Yes, but not my England.”

“We all live in a world,” she said vaguely, “the view of which is often clouded… by eyes that see differently. This”—she gestured—“is how we see it.”

“We?”

“Mystics and magicians.”

“Oh. And me—I’m a…?”

“Muddle.”

“Right. And that means…?”

“You’re very good at what you do best,” Harry said sweetly. “Getting in a muddle.”

He gave her a wounded look. She did not notice.

The carriage shuddered, rocked, and the platform clock nodded right on time. Voices rose. Box peered over the screen; everyone wore clothes from another century.

“Hungry?” Harry asked when the train finally slid forward.

“I could eat a horse,” Box said—just as a horse clopped past the window. He blanched.

“Careful what you wish for,” Harry said. “Follow me.”

They stepped through to the next carriage—Art Deco perfection. Every passenger matched it. No one gave them a glance. Through again: the buffet car, all silverware and clinking glass. A waiter with two noses glided over.

“A table for two, madam?”

“Yes. By the window, if possible.”

Box stared. Two noses. Working independently. He couldn’t help it—he grinned. Harry ignored him.

Once seated, the waiter’s twin sniffers twitched in harmony. “Have you chosen, madam?”

Harry ordered. “My friend will have the same.”

“That’s not fair,” Box protested softly. “I don’t even know what you—”

“Pray it isn’t snake,” she said dryly.

He gazed out at rolling countryside and promised himself, as he always did, that one day he’d buy a small place and live a quiet life among hedgerows and mist.

The two-nosed waiter returned with a trolley and began unloading dish after dish. Box’s eyes widened. “All this for us?”

Harry nodded. The waiter leaned in and did a thorough, professional sniffing.

“What’s he doing?” Box whispered, trying not to laugh.

“Smelling,” said Harry.

“But I was only joking—”

“I told you: be careful what you wish for.”

It was not snake. It was extraordinary. When Box finished, he drained a cut-glass tumbler of ice-cold water with noisy gratitude.

“Was everything satisfactory, sir?” the waiter asked.

“Perfect,” Box beamed. “Best meal I’ve ever had.”

The waiter smiled peculiarly. And kept smiling. Box, unnerved, dug in his pockets and spilled a fistful of coins onto the trolley. “Er—thank you.”

Both noses twitched. The smile vanished. “I have never been so insulted,” the waiter hissed. He pinched one coin like it might give him a rash. “Muddle money.”

Box shrank.

“Give him this,” Harry murmured, passing over two gold coins. The waiter bit each, restored to good humour, and glided away.

“Lesson learned?” Harry said, Cheshire-wide.

Box nodded weakly. “Yes.”

They returned to their seats to find two cloudy white drinks waiting. “Complimentary,” said Harry.

“What is it?”

“Taste,” she said.

He hesitated. “You first.”

She tossed hers back. He followed, and a million bright bubbles popped on his tongue—mango, chocolate, vanilla, something like childhood.

“Fantastic,” he gasped. “What is it?”

“Fizzing Fruit Juice,” Harry said. “Local speciality.”

An attendant with, mercifully, only one nose stopped by to confirm their bliss. Box let Harry handle the niceties. Then, “How long till Hagswords?”

“Eighteen hours,” Harry said, gaze fixed on the window.

“Eighteen—? Where are we going, Timbuktu?”

She didn’t answer.

“What are you looking at?”

“Owls,” she whispered.

“Owls? What owls—” He followed her finger and saw them: dozens, then hundreds, winging toward the train in dark, silent waves.

“Crikey,” he breathed. “What do they want?”

“Me,” Harry said, voice gone flat. “They want me.”

Chapter Eight

Owls, Familiars and Necromancers

The two cousins pressed their faces to the windowpane, watching as the dark shapes of owls swept nearer through the night. The birds moved with uncanny speed, gliding alongside the racing train as though the wind itself were their ally.

“How can they fly so fast?” Box whispered, awe and fear wrestling inside him.

“Owls are Familiars,” Harry murmured.

“Familiars?”

“Yes. Familiar Spirits—controlled by Necromancers.”

“As in… wizards?”

Harry nodded grimly, her reflection sharp in the glass. Box decided not to press the point. It already felt as if his nerves were hanging by one last thread.

Outside, the sky was thick with wings. The owls were almost upon them now, yet the other passengers sat calmly chatting, drinking tea, and leafing through newspapers as if nothing unusual were happening.

“Why aren’t they reacting?” Box hissed. “Anyone would think they can’t see them!”

“They can’t,” said Harry. “Those owls are marked for us—for me, really. That’s why only we can see them.”

“That’s ridiculous!”

“Denial won’t help,” she said flatly. “Watch.”

The owls hit the windows.

Thump. Thump. Thump.

One after another, they threw themselves at the glass with suicidal fury, beaks striking like hammer blows, talons scraping. Each impact rang through the carriage like the tolling of a bell.

“We can’t just sit here!” Box cried. “Do something!”

With a sly smile, Harry drew her wand. “Just because we can’t make them go away doesn’t mean we can’t deal with them. Let’s see what this little beauty is capable of, shall we?”

Box’s heart jumped. He had nearly forgotten the wand they’d built together. “Yes! Go on—use it!”

A couple in the next section peered over the glass divider.

“Sorry!” Box said quickly. “Bit of a coughing fit!”

The couple returned to their conversation.

Outside, several owls struck the window at once. A spiderweb crack crept across the pane.

Box spoke quietly but firmly. “I think you’ll find the third button quite useful.”

Harry waved the wand from left to right and murmured, “Abracadabra.”

The window vanished.

A burst of freezing wind tore through the carriage. Papers flew. Box grabbed the armrests to stay in his seat.

Then Harry pressed the third button and repeated the word. A flare of blinding blue light erupted from the wand, slicing through the night. The beam swept across the sky like a lighthouse, striking every owl within a hundred yards. The Familiars dropped, one by one, limp as stones.

“Wow,” breathed Box, stunned. “That’s impressive!”

Harry allowed herself a faint, tired smile. Then the last owl—one the wand had missed—burst through the open space with a shriek. It clawed at her hair, her face, its talons flashing.

Harry screamed, dropping the wand. Without it, she was defenceless.

Box snatched it from the floor and pressed the second button.

A tongue of flame roared out—just as it had for his father—and engulfed both bird and cousin. Harry cried out. The owl shrieked louder, a burst of feathers and smoke, before collapsing to the floor, charred to a crisp.

“Are you all right?” Box gasped, horrified at his own heroics.

“Y-yes,” Harry panted, singed and furious. She gave the blackened remains a kick. Then she reclaimed the wand and muttered, “Arbadacarba.”

The window reappeared. Her burns and scratches faded from sight.

“Do you think we’ve seen the last of them?” Box asked.

“Hardly,” Harry said. “That was only the beginning.”

Box looked out at the passing landscape—half-familiar hills and ghostly hedgerows. His mind returned to the words Harry spoke when using the wand. “I’ve been thinking—”

“A Muddle, thinking?” she teased.

He ignored her. “Those words you say—aren’t they a bit… corny?”

“Corny?” she repeated icily.

“Yes! ‘Abracadabra’? Every second-rate magician says that on television.”

“Just because they use it,” said Harry, “doesn’t make it less powerful. Have you ever wondered where those words came from?”

“No,” he admitted meekly.

“I’ll tell you. Though it may do little good—you being a Muddle and all.” She lifted her chin. “Those ‘corny’ words have been handed down for centuries. I may despise Hagswords and its masters, but even I respect the power of language.”

“Oh,” said Box, suitably chastened.

“And if you’d like a demonstration,” she added coolly, “I’ll oblige.”

“Yes, please,” he said at once.

Harry tapped the table with her wand. “Hey presto.”

The table vanished.

Box’s mouth dropped open. “Wow, I see what you mean!”

“Do you?” She arched an eyebrow. Then she reversed the spell: “Otserp yeh.”

The table reappeared, gleaming as before.

“Brilliant!” Box said. “And you didn’t even press any buttons!”

“No—none,” Harry said, pleased despite herself.

Then, with mock innocence, she pointed the wand at his face and murmured, “Hocus Pocus.”

Box blinked. “Nothing happened.”

“Are you sure?”

He glanced around. Nothing seemed different. “Yes, I’m sure.”

“Look in the window,” she said.

He turned—and leapt back with a yelp.

He had two noses.

“Get rid of them!” he bellowed. “GET RID OF THEM!”

The couple peered over again. Box ducked below the divider. “All right, Harry, I get it! Just put it back—one nose, please!”

Laughing, she waved her wand. “Sucop Sucoh.”

Box slowly checked the window again. His face, blessedly, was back to normal. “Thanks,” he muttered.

“Pardon?”

“I said thanks, all right?”

Harry’s frosty manner softened a touch. “Accepted.”

They fell into silence—Harry plotting, Box pretending not to worry. Dusk slid into night. Box shifted and squirmed in his armchair, trying to find comfort for the long journey ahead. Propping his feet on the table, he closed his eyes.

“What are you doing?” Harry asked.

“Trying to sleep.”

“Not here.” She stood. “Come on—we have a sleeping compartment.”

“Really?” He opened one eye.

Without answering, she swept off through the connecting door. In his scramble to follow, Box toppled out o the chair and banged his head on the table. “Ow!” Rubbing the lump, he hurried after her.

The next carriage was even finer than the last, all brass and mahogany. Then the buffet—empty now, chairs stacked, lamps dimmed. Beyond it, Harry stopped and opened a door. “This is us.”

Inside were two bunks, tidy and inviting. Box climbed to the top, kicked off his shoes, and fell instantly asleep.

Below, Harry lay awake, eyes on the ceiling, wand within reach.

When Box awoke, the train was still rattling through the ink-black night. “Are you awake?” he whispered.

“Yes,” Harry murmured. “Quietly.”

“Can I ask something?”

“Go on.”

“Those Necro—what were they called again?”

“Necromancers.”

“Right. Why do they want you so badly? Dead or alive?”

Silence. Then Harry said, “Necromancer is just a fancier word for wizard.”

“I know that,” Box said patiently, “but why are they after you?”

Another pause. Then: “Because I left something behind.”

“What was it?”

“It’s none of your concern,” she said coldly. “Go back to sleep.”

He tried again, but she ignored him utterly.

“Wake up, sleepyhead,” Harry said, prodding him in the ribs. “We’ve arrived.”

“Mmm—what?” Box mumbled.

“It’s five-thirty.”

“Five-thirty! I need more sleep.”

“No, you don’t. We’ll be there in half an hour.”

“At six in the morning?”

“I did tell you. Can’t you Muddles remember anything?” She opened the compartment door. “I’ll see you in the buffet car.”

The door banged behind her.

Box sat up, yawned, and promptly forgot he was in the top bunk.

He rolled off and hit the floor with a thud.

“Argh!” he groaned. “What else can happen to me?”

Chapter Nine

Hagswords Bound

Breakfast on the train had been magnificent — smoked kippers that flaked at the touch of a fork, warm bread with curls of golden butter, and endless cups of steaming tea poured by the same two-nosed waiter from the night before. He stood beside their table now, bowing slightly.

“Was everything to your satisfaction?”

“Yes, it was wonderful,” Box assured him, still working on his third slice of bread.

The waiter gave Harry that same peculiar smile — the one that had unnerved Box the previous evening. Unfazed, Harry handed him two gold coins. “Thank you. Perhaps we’ll see you again soon.”

The waiter’s two noses twitched approvingly. He pocketed the coins, cleared the table, and glided away, humming a tune that smelled faintly of lavender and coal dust.

Outside, dawn was clawing its way over the horizon. The landscape had changed; the train was now high in the hills, the trees replaced by scrub, gorse, and clusters of strange blue shrubs that glowed faintly in the morning light.

“What are those?” Box asked, pressing his nose to the glass.

“What are what?”

“The shrubs—oh, they’re gone.” He blinked. The hillside had vanished behind a wall of station platforms and grey stone. “Never mind.”

The brakes hissed. The train slowed, shuddered, and stopped.

Harry leapt down from the carriage with enviable agility. Box followed with all the caution of a man stepping off a cliff. A blast of steam erupted beneath him and he jumped half a foot in the air.

Harry laughed. “You’re hopeless.”

The guard waved his green flag, the whistle sounded, and Mallard steamed away into the mist. The platform was suddenly quiet — eerily so. No chatter, no footsteps, not even a pigeon’s coo.

“Are we the only ones?” Box asked.

“It looks like it,” said Harry. “But Hagswords was never exactly popular.”

“Wasn’t it?” he asked faintly, hoping she wouldn’t elaborate.

They left the platform. Box looked around in confusion. “Where is everyone? No porters, no staff…”

“They’re here,” said Harry. Then, with a glance at his puzzled expression, she added, “You just have to look properly.”

He tried. He squinted, concentrated, and nearly gave himself a headache. “Sorry, I don’t see anyone.”

“Then try looking for those who aren’t living,” she said simply. “We’re not in your world now.”

Swallowing hard, Box looked again. And this time—he saw them.

An elderly man in a tattered uniform approached, tipping his cap. “Good morning, sir. Can I be of assistance?”

Before Box could reply, another figure appeared — stately, silver-haired, translucent. “Mr Spectre,” he said, “everything all right?”

“Yes, sir,” said the first. “Just helping these souls on their way.”

“Good. We’ve too many lost ones wandering as it is.” The stationmaster drifted away to his office, from which faint, melancholy music began to play.

Box’s voice trembled. “What sort of a place is this?”

Producing their tickets, Harry said coolly, “Please clip them so we may be on our way.”

The ghostly collector peered at the paper. “Ah, from Muddleland. A strange time to be heading to Hagswords — term started weeks ago.”

Harry’s expression darkened. “The tickets.”

Chastened, the man clipped them and stepped aside. “Safe travels,” he said, his voice fading like mist.

As they crossed the station yard, Box glanced back and froze. Faces — pale, unblinking faces — were pressed against every window of the old building, watching.

“Harry, you’ll never believe what I just saw—Harry?”

She was already halfway down the road.

“Wait for me!” he yelled, running after her.

When he caught up, panting, he asked, “How far is it to Hagswords?”

Harry pointed toward a distant mountain, its peak capped with a ring of thunderclouds. “That far.”

Box’s shoulders slumped. Then, brightening: “What about the flying carpet?”

Harry stopped dead, turned slowly, and regarded him as though he were a particularly dense pebble.

“Do you think I’m stupid?”

“No,” he mumbled. “I just thought—”

“You weren’t thinking,” she snapped. Then, softening, she sighed. “All right, maybe I was harsh. Come on — I’ll explain as we go.”

They walked. For an hour they talked more than they ever had before. Box told her about his love of circuits and electricity, how he dreamed of combining science with magic. Harry listened, almost kindly, then spoke of her life at Hagswords — of strict teachers, endless rules, and the moment she decided never to be controlled again. For the first time, Box began to understand her. Beneath the stubbornness and arrogance was a girl who had learned to fight because she’d been left with no other choice.

“Well, that’s enough sentiment,” she said briskly. “We can’t use the carpet — too easy to spot from above.”

“But if they know we were on the train,” Box asked, “why not send more owls?”

Harry glanced up. “Careful what you say.”

He ducked instinctively. “They’re coming?”

“No,” she laughed. “You got away with it this time.”

A rumble of wheels interrupted them. A cart approached, drawn by six enormous shire horses, their hooves thudding like drums. “Quick!” said Harry. “Thumb up!”

“Like hitchhiking?”

“Exactly.”

The driver pulled up, glasses slipping down his nose. “Whoa there! Morning!”

“Good morning,” said Harry sweetly. “Are you heading anywhere near Hagswords?”

“Students, eh? Bit late in the term,” he said, removing his spectacles and squinting at them. “Can’t see a thing through these. Don’t know why I bother wearing ’em.”

“May I see them?” asked Harry, smiling.

He handed them over. “They’re beyond fixing. Scratched to blazes.”

“Leave that to me,” she said. Whispering, “Erotser selcatceps,” she tapped the lenses with her wand.

“Try them now.”

The man perched them on his nose — and gasped. “Clear as crystal! Well, bless my soul! Hop aboard, both of you — free ride to school!”

They climbed into the cart, settling among the bales of hay. The shire horses plodded forward at a stately pace. It was peaceful, if slow. The driver, enchanted by his newly perfect vision, barely spoke, too busy marvelling at every stone wall and hedge he hadn’t seen properly in decades.

After an hour of monotony, Harry and Box dozed off in the straw.

When Box awoke, the cart was jolting violently. The horses were galloping far too fast. Something was wrong.

“Harry!” he shouted. “Where are you?”

“Up here!” she yelled back.

Scrambling forward, he saw her on the driver’s bench, wrestling with the reins. The old man lay crumpled at her feet, his face scratched and bleeding.

“What happened?” Box gasped.

Harry looked skyward.

The answer was there.

Dozens of owls, black shapes against the pale morning, were diving toward them.

“I said it before,” Box yelled, “and I’ll say it again—you must have really angered someone!”

The Familiars attacked in waves, slashing, pecking, hurling themselves at the cart. A huge owl smashed into Box’s chest, nearly knocking him backward. Harry grabbed him just in time.

“Hold the reins!” she cried. “I’ve got an idea!”

Another owl swooped, talons raking his shoulder. Harry yanked open her bag and pulled out the worn flying carpet. She spread it over the old man’s body at her feet.

“Step on it!”

Box obeyed instantly.

“Up, up and away!” she screamed.

The carpet shuddered, trembled—and soared. It ripped free from the cart, carrying them skyward in a wild, dizzying rush. Below, the shire horses bolted in terror. The cart overturned, splintering on the road.

The owls followed.

Harry urged the carpet higher, faster. Box looked down and wished he hadn’t. The swarm descended upon the cart, upon the driver and the horses, until all that remained were feathers and smoke.

He turned away, sickened. Neither of them spoke.

In silence, they flew on toward the dark mountain of Hagswords.

Chapter Ten

Subterfuge and Some Berries

“Down—slowly down,” Harry murmured, and the carpet drifted to a halt in a scrubby hollow a good distance from Hagswords.

“Why are we stopping here?” Box asked, thinking more of his aching feet than their peril.

Harry answered him with a look, folded the carpet with maddening neatness, and stowed it. For a long while she studied the school. Perched on a lonely, knife-edged hill, Hagswords looked less like a school than a fortress that had mislaid its moat.

“We have to get in without being seen,” she said at last.

“That sounds difficult. Impossible, even,” Box groaned, eyeing the sheer slope.

“There’s more than one way to skin a cat,” Harry said absently, still watching the walls.

Box winced at the picture that painted. “What’s the plan, then?”

“We wait for dark,” Harry said, settling behind a boulder. “Only then is it safe to make the first move.” She closed her eyes and rested.

Day hung stubbornly on. Box sat, too, and drifted into a doze crammed with owls, blood-spattered faces, smoking carpets—and an especially awful version of himself covered in noses. He woke yelling, “No more noses! No, no—no more noses!”

“Wake up. It was a dream,” said Harry.

“It felt real.”

“It wasn’t,” she said, final as a door click.

He checked the sky. “Past six, I’d guess—and my stomach agrees.”

“Let’s see what we can find,” said Harry, rising to scout the rocks. “Ah.” She knelt beside a blue shrub wedged in a crack of stone.

“That’s what I asked you about on the train,” Box said. “What are they?”

“Rub-a-Dubs,” she replied, mischievous smile engaged.

“What sort of name is—”

“A silly one,” she said. “After you taste them, you won’t care.” She plucked a handful of berries—bright blue with neat orange stripes—and offered them.

Box inspected them with suspicion. “They’re safe?”

“As safe as most things in life.”

“Not very reassuring,” he muttered, but he chose one and set it on his tongue. A pleasant blackberry note… then a detonation of fire. His eyes watered. “It’s burning me! Water! Water!”

Harry laughed and offered more berries.

“Are you mad?” he spluttered. “I’m not eating another—”

“That’s the only way to reach the next stage,” she said.

“Next stage? The first one is killing me!”

“Refuse and you’ll burn for an hour. Or more.”

“And if I eat another?”

“Untold pleasure,” she said softly.

He froze. “Untold pleasure?”

She nodded.

“It isn’t a drug?”

“Of course not,” she said, stung.

“Then—fine.” He popped a second berry.

“Wow,” he breathed. “Oh—wow.”

“Burning gone?” Harry asked.

“Gone!” he grinned. “Replaced by… I don’t even have the words.” He ate another. And another.

When at last he stopped, rosy and blissful, he said, “I’ll fetch a few more. Want some?”

“No. And you’ve had enough. No more.”

“Why not? There are loads left.” He scratched his calf. “Ow. Itchy.”

Harry smiled.

“What?” He ripped at his collar, then his shirt. A violent itch raced across his chest. “Oh. That’s why they’re called Rub-a-Dubs. Side-effects! Why didn’t you warn me?”

“Would you have listened?”

He said nothing, just scratched and scratched until the itch skulked away.

“That was a rotten joke,” he muttered.

“Who’s laughing?” Harry said. Then, briskly, “Still hungry?”

“No. Perfectly full, actually.” He glanced at his bare wrist. “It’ll be dark soon.”

“It will,” Harry said. “And owls prefer it that way.”

Night finally poured over the hillside like ink. Neither cousin quite trusted the other’s judgment, but necessity breeds cooperation. A thin sliver of moon shouldered up over the rim of the world.

“Come on,” Harry whispered. “Time to go.”

They slipped from the boulder’s shadow. Box stubbed his toe on a rock and swallowed a yelp. As they climbed, the school bulked larger, its wall looming like a cliff.

“What do we do when we get there?” he whispered. “We can’t just knock and ask to be let in.”

Harry, who disliked unnecessary words, made none.

Sometimes Box thought he heard wings, but nothing showed. At the base of the wall he exhaled shakily. “Phew. I thought we’d never make it.”

“Getting here is one thing,” Harry said. “Getting in—unseen—is another.” She fingered the clasp of her bag.

“The carpet?” Box guessed.

“Out of the question,” she said. “Unless you want every owl in the county on our tail.”

“Then what?”

She drew out a small glass sphere alive with faint, wandering lights. “This.”

Box stared, entranced. “What is it?”

“A Philosopher’s Marble.”

“A philosopher’s what?”

“Marble,” she said, as if speaking to a slow radio. He reached for it. She slapped his hand lightly.

“Can I—?”

“No. Dangerous, especially for you.”

“Where did you get it?”

“Never you mind. What matters is what it can do.”

They found a shallow alcove in the wall. Harry cupped the Marble in both hands. It began to glow—softly, then fiercely, until its light washed the stones in a pearly radiance.

“Wow,” Box whispered, edging away. “But what is it doing?”

“Try using that Muddle brain?” she murmured.

He swallowed the retort. “Can it get us inside?”

“Of course. The trick is doing it without notice. Keep watch.”

He peered both ways. “All clear. All systems are—” He caught her look. “Forget I said that.”

“Already forgotten,” she said, lowering her voice to a chant:

“Crioninous crionan shraholarman skryolamb,

let us into the school select,

scryoumeno scry— It’s done.”

“What language is—”

“Shh. Watch.”

At first he thought nothing had happened. Then came a low, grinding moan, stone on stone. The glow dimmed. A massive block slid inward, leaving a neat, person-sized gap.

Harry slipped through, checked both ways, then beckoned.

Inside, water dripped somewhere in the dark. The Marble gave one last glow; the wall sealed itself behind them with a muffled thud. Harry pocketed it, drew the wand, and pressed a base button. The tip blossomed with clean, white light.

Box couldn’t help a small, proud smile: magic and electrics, humming together.

They stood in a damp, chill undercroft—more dungeon than basement. The air smelled of old stone, old water, and old secrets.

“Where now?” Box whispered.

Harry tilted her chin toward a shadowed stair curling upward into the dark. “Up,” she said.

Chapter Eleven

Owl, Owls, and Yet More Owls!

Because she had once been a student at Hagswords—escaped or not—Harry knew the shortcuts. She found a mouldy door sunk into a corner and eased it open to a spiral stair.

“It’s awfully rusty,” Box muttered.

“Keep close,” Harry said, ignoring the rust and starting up.

He shadowed her to a narrow landing. Box swiped a low cobweb away and made a face. “What a dismal place. I’d pick my grammar school at Gunnersbury over this dump any day.”

“Appearances can be deceptive,” said Harry. “Listen. Past this door we’re inside the school proper.”

“Classrooms?”

“Something like that. Most students should be in their Houserooms. That doesn’t mean we relax.”

“You can depend on me,” Box whispered. “No relaxing. No dropping anything. Not even my guard.”

Harry pressed a finger to her lips and turned the handle. The door creaked. Dim light seeped in. She kept her wand glowing.

“It’s much nicer in here,” Box breathed, stepping into a grand vestibule striped with polished stone and hung with paintings. “These must be worth a fortune!”

“Remember what I said,” Harry replied. “Appearances.”

Box, heedless, drifted up the broad stair, entranced. Portraits, landscapes, wildlife, still life—each more vivid than the last. “They’re so lifelike,” he whispered. His fingers brushed a bowl of fruit; an apple felt cool and round beneath his touch. He tugged it free, rubbed it on his sleeve, and took a bite. “You won’t believe what I just—”

“I will,” said Harry. “Everything we do has consequences, including stealing from paintings.”

“What do you—”

“Look again.”

Box glanced up. His jaw dropped. “They’re looking at me! Harry, the people, even the animals—they’re all staring! Make them stop!”

“Only you can.”

“How?”

“Make amends.”

“Amends? How?”

“Ask.”

Box faced the gallery, cheeks hot. “I’m sorry I took the apple. When I felt it was real I couldn’t resist. How can I make it up to you?”

The painted faces studied him. At last a knight in armour astride a destrier spoke. “To make amends is no easy matter. In my day you would have met me in a joust.”

“L—lances?” Box stammered.

“And perhaps to the death.”

“T—to the d—death?”

The knight sighed. “Times have changed. No jousting. Now we settle for a promise.”

“A promise?”

“That when your quest is over and you return home, you will do all in your power to integrate these spirited paintings of Hagswords into the outside world.”

Box flushed. “I’m a Muddle. Are you sure you want to be integrated into a Muddle world?”

A lively argument erupted across frames—human voices, animal murmurs. At last the knight said, “Yes. If that is the price, so be it. Muddles and Mystics have been apart too long.”

“Then I promise,” Box said, relieved and a little proud. The faces softened; the gallery returned to its painted poise.

“You think you got off lightly,” Harry murmured. “Time will tell. Come on.”

As they moved on, Box asked, “How did he know I was on a quest?”

“The paintings know everything that happens at Hagswords,” said Harry.

What followed felt to Box like a royal tour and a maze combined. Up wide staircases and through stately halls, down into paneled chambers, up again into rooms grander still. Hagswords was far bigger on the inside. After a while Box couldn’t help asking, “Are you lost?”

Harry’s look could have curdled butter. He did not repeat the question.

He kept his distance from every frame they passed. The paintings were brilliant, yes; they were also watching.

“Where exactly did you leave it?” he tried.

If she told him the truth, he might guess too much. “In a study room,” she lied.

“Hmm.” He did not sound convinced. “Any shortcuts?”