The Haunted Chip Shop

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Two — A New Face Every Night

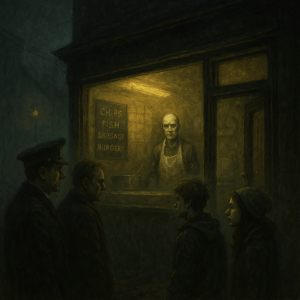

By day, the chipper was a trick of the fog. Blink and you’d think the place was shut: blinds down, no movement, no queue, no smell of salt and grease. By dusk, though, the amber light bloomed again, and the counter was never empty.

The people behind it changed each night. Not in the way a shop hires teenagers for summer shifts, not in the way staff turn over slowly and you notice it on your third visit. No — this was every single night.

The Woman with the Egg Eyes

On Monday, a woman with eyes like boiled eggs served chips. They bulged, white and slick, with a pinprick of yolk where pupils should have been. She scooped from the fryer as if blind, but never spilled a chip. People queued anyway. Some swore she stared right through their skulls, yolks drilling down into the marrow.

Mrs. Brigid Kavanagh took one look and muttered, “That one’s not from Tullow.” Then she said nothing else, because to comment further felt like inviting something closer.

The Boy with the Greasy Hands

On Tuesday, it was a boy, no older than sixteen, grinning so wide the corners of his mouth creaked. His hands shone with oil that never dripped, never dried. Every time he brushed a coin, the metal smoked faintly, like bacon in a pan. He counted change with the care of a surgeon and pressed the notes into palms so firmly the smell clung for days.

Tommy Doyle noticed the boy didn’t blink. Not once, through the whole evening.

The Silent Old Man

Wednesday brought silence. An old man manned the counter, skin creased like butcher’s paper, lips thin as a knife’s edge. He took orders with a nod, served with precise motions. Not a sound passed his throat. Not when Declan O’Connor greeted him. Not when Breda Maher asked what fish they used.

But when Sergeant Flanagan dropped a coin on the floor, the man turned his head sharply — not toward the clink, but toward Flanagan’s throat, watching the shape of his Adam’s apple as he swallowed.

Gossip in O’Connor’s

By Thursday, the town was whispering over pints.

“They’re blow-ins,” someone said. “Travellers, maybe. Passing through.”

“Passing through where?” another asked. “They’ve never left the counter.”

“Did ye ever see them after hours? Any of them?”

Silence answered.

Declan polished a glass until it sang. “I’ll tell ye what’s true,” he said. “There’s no one livin’ in Tullow who owns that shop. Never paid a bill. Never cashed a cheque. Never set foot in Mass.”

“And yet it’s open every night,” Mrs. Kavanagh muttered. “Always open.”

The conversation ended there, because the pub lights flickered — just once, like a wink — and the smell of vinegar drifted in though no bag of chips had crossed the threshold.

Tommy and Sinéad’s Dare

Tommy Doyle and Sinéad Walsh met at the corner that night, fog rolling between their shoes.

“Same again?” Sinéad asked, though her tone was more warning than invitation.

Tommy shoved his fists in his pockets. “I want to see if it’s true.”

“What’s true?”

“That it’s never the same person twice.”

She didn’t stop him, because she wanted to see too. Curiosity’s a door you can’t close once it’s been nudged. Together, they walked into the jaundiced glow, where the window hummed with light and the fryer hissed like a throat boiling secrets.

Tonight’s cashier was different again: a woman whose hair dripped with water that left no puddle, as if she’d stepped straight from the Slaney. She smiled without opening her mouth, and her eyes were pale as river stones.

“Chips?” she asked, her voice a ripple over water.

Tommy’s throat tightened. Sinéad reached for his sleeve, but he’d already stepped to the counter.

Because in Tullow, once you’d entered the chipper, leaving without ordering was the one thing nobody dared.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Three — When Food Learns Your Name

The first strange bite was almost a joke.

A bag of curry chips, steaming hot, handed to Michael Doran after the Friday dance. He and his mates staggered out into the square, grease soaking the paper bag. He popped one in his mouth and laughed, half from drink, half from hunger.

Then the chips hummed. Not loud enough for the others to hear—just low, buzzing, a tune playing against his teeth. He spat it onto the ground, swore, and laughed again. His friends roared with him, shoved each other, told him he was cracked.

But when the next chip sang the same tune, slow and low like a dirge sung underwater, Michael dropped the bag and never ate from the chipper again.

The Whispers Spread

Word drifted through Tullow like steam: food from the chipper wasn’t just food.

At first, it was harmless. Chips that hummed lullabies. Battered sausages that whispered bad jokes, filthy as graffiti. A burger that muttered, “Hungry, are ye? Hungry forever,” between each bite.

Teenagers dared one another to order and eat. They crowded on the church steps after closing, laughing with grease on their fingers, chips singing from their bags. The braver ones came back week after week, claiming the food told them secrets of the future.

But not all secrets should be told.

The Widow’s Snack Box

Breda Maher, a widow for twenty years, finally gave in to temptation. She ordered a snack box. In the square outside, she lifted a drumstick to her lips.

She bit down once.

And the chicken whispered the name of her husband. Not as she knew him in life, not as the town knew him in his coffin—but the name he used the night he begged her not to bury what she buried. The name he said when the shovel cut earth.

The meat in her mouth turned slick and heavy. She dropped it, gasping, her throat burning with old dirt. She never touched the food again.

Declan O’Rourke’s Burger

One night, Declan, drunker than was decent, ordered a burger and chips. He ate standing under the streetlamp, grease dripping onto his shirt.

The burger spoke in his own voice. Clear. Measured. It described the hour and manner of his death: three weeks hence, drowned in the Slaney, lungs burning, hands clawing riverweed.

Declan laughed, so loud the square echoed. He roared, grease spraying from his lips. “I’ll drink to that!” he shouted, raising the burger as though to toast it.

Three weeks later, he staggered home from the pub, stepped onto the riverbank, and never returned. The Gardaí called it misadventure. The town called it proof.

Confession in Grease

By now, the chipper was no longer just a place to fill your stomach. It was confession in grease. People queued for it. They went in with coins in their hands and came out pale, shaken, mouths full of things they hadn’t wanted to know.

No priest could absolve what the chipper dredged up.

And no one ever managed to stop eating.

Because once food has spoken to you, silence tastes wrong.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Nine — The Back Window

I. Gathering at the Table

No one really liked being in Mrs. Kavanagh’s house after dark. It was too quiet, too ordered, as if the walls themselves had been pressed into submission. But on that night, with the fog thickening outside and the chipper’s jaundiced glow leaking across the square like a lantern in a crypt, there was nowhere else to gather.

The kitchen smelled of polish and lemon rind. The clock ticked in a polite, persistent manner. On the table—a long pine board with a burn mark in the shape of a boot heel—sat four cups of tea no one touched, four saucers catching drips, and a plate of ginger snaps that remained unopened.

Sinéad laid her piece of paper down. It wasn’t quite a map, but it was the best she could do. She had sketched the chipper as a square block with windows on the front, the door in the middle, and, in the back, a smaller square marked in heavy pencil: BACK WINDOW. She had added arrows pointing to it, the way children might draw battle plans with stick figures.

“That’s where we go in,” she said firmly. “Not the front. The front’s where it wants us. The bell, the cloth, the counter—it’s the mouth. If we’re to learn what’s inside, we go in through the teeth at the back.”

Sergeant Flanagan sat hunched, bandaged hands pressed to his knees. He looked like a man too tired to argue, but he tried anyway. “You don’t go in through anywhere. You leave it alone. That place isn’t a shop anymore—it’s something else. And whatever it is, it wants us. It’s writing our names, for God’s sake.”

“That’s why we have to look,” Sinéad replied. Her voice shook, but she held his gaze. “Declan’s dead. But what killed him is still there. Still cooking. Still calling. If we don’t face it now, we’ll all end up in the river.”

Tommy rested his hammer on his lap. He hadn’t said much, but his eyes were lit with that hard, stubborn glint that made people trust him—or follow him into trouble. “Then it’s settled,” he said. “Tonight. Before the fog thickens.”

Mrs. Kavanagh got up without a word and fetched two lemons from her larder. She placed them on the table as if they were relics. “Hold these. Don’t let go. And whatever you do, don’t eat.”

The lemons glowed pale in the lamplight. No one laughed at the strangeness of the instruction.

II. The Lane

They left just after dusk. The town was swaddled in fog already, though it clung to the cobbles for now, not yet risen to the windows. Church Street was silent; the pub’s lights burned but no sound carried. It was as if Tullow itself were holding its breath.

The lane behind the chipper was narrow and mean, hemmed in by walls damp with moss and bins that stank of old cabbage. The ground was slick underfoot. Rats skittered from the sound of their boots.

And there, above a stack of crates, they saw it: the back window. Small, square, salt-crusted from years of river spray, its glass jaundiced and smeared as though greasy hands had dragged themselves across it from the inside.

Sinéad climbed onto the crate first, Tommy steadying it with one hand. She pressed her sleeve to the glass. Her reflection swam back—blurred, distorted, smiling too wide. Too many teeth.

“It’s warm,” she whispered. “The glass is breathing.”

Flanagan took out a crowbar and wedged it under the frame. Metal screeched against wood, loud as a scream.

Inside, the fryer hissed.

“Faster,” Mrs. Kavanagh urged, her rosary clutched so tight the beads left marks in her palms.

III. The Window Opens

With a sound like tearing fat, the frame gave way. The window swung outward, and a wave of fryer air hit them—thick, cloying, the smell of chips so rich it coated their throats.

“Don’t breathe it,” Sinéad muttered, pulling her scarf over her mouth.

They leaned in.

The kitchen wasn’t a kitchen anymore. The fryer stood at the centre like an altar, its oil surface rippling though no basket moved. The counter stretched on and on, longer than the building should allow, vanishing into greasy haze. And on it lay dozens of paper bags—closed, steaming, breathing.

Each bag bore a name, written in slick black grease.

DECLAN. BRIGID. SINÉAD. TOMMY.

Names of neighbours. Names of children. Names of the dead. Names of people not yet born.

On the wall, the cloth twitched. Letters began to scrawl themselves in fat, greasy lines:

HUNGER IS MEMORY.

FEED US.

The fryer bubbled as if laughing.

IV. Declan’s Voice

“Close it,” Flanagan croaked. His bandaged hands trembled on the crowbar. “Close it before it—”

But Sinéad was leaning in. Her eyes fixed on a bag in the centre, quivering more than the rest. From it came a muffled voice.

“Sinéad,” it whispered. “Don’t leave me. It’s dark. It’s hot. Please.”

Her face drained. Her hand shot forward before Tommy caught her wrist.

“That’s not him,” he hissed. “That’s what’s left. It wants you to open it.”

Her eyes brimmed. “What if he’s still—”

“He’s not,” Mrs. Kavanagh snapped. “And you know it. Shut the window.”

But the fryer hissed louder, bubbles leaping as though something beneath was thrashing to surface. The bags writhed. One split open at the seam, spilling not chips but pale, twitching fingers, slick with oil. They scrabbled across the counter, leaving trails of fat.

The voice grew louder, distorted now, layered with others: “Sinéad Sinéad Sinéad—”

V. The Struggle

Flanagan shoved the window shut, searing his bandaged hands on the hot glass. He gritted his teeth and pressed until the latch clicked.

The cries muffled. The fingers recoiled, dripping back into the bag. The fryer hissed in fury, bubbles spitting against steel.

The lane fell still. Only the drip of distant water remained.

They staggered back, coughing, eyes watering from the fryer air. Mrs. Kavanagh clutched her coat—juice from the lemons in her pocket had split their skins, running down her lining. The sharp citrus cut through the grease like a knife.

Sinéad slumped against the damp wall, shaking. “It knows us,” she whispered. “Every name. Even the ones we’ve never spoken aloud.”

Flanagan shook his scorched hands. “Then we give it nothing more. No words, no songs, no names. We starve it.”

But the fryer’s hiss still echoed in their ears. And the image of those bags—breathing, waiting—clung to their eyes long after the window closed.

VI. Return to O’Connor’s

When they returned to the pub, the snug was silent. Even the clink of glasses seemed too loud. They told what they’d seen in fragments, their voices hollow. No one touched the plates of chips on the tables, though their smell filled the room.

“Breathing bags?” muttered one man, paling.

“Names in grease,” said another, crossing himself.

“Declan’s voice,” Sinéad whispered, eyes glazed.

The barmaid took the untouched chips and swept them into the bin. The grease hissed on the fire as if alive.

Father Pádraig wrote a single word on his pad and held it up: FAST.

VII. The Mirrors

That night, Tullow did not sleep. Fog pressed against windows, heavy as wool. Every mirror in town clouded with steam. And when the condensation cleared, one word remained, drawn in vinegar-sour lines:

OPEN.

It appeared in bathrooms, in shopfronts, in the silvered glass above the church font.

By dawn, the whole town knew the chipper had written its demand in every house.

VIII. The Final Echo

Sinéad woke before sunrise, heart hammering. She thought she heard a bag breathing under her bed. She struck a match and found nothing but shadows.

From the street came a sound—the bell above the chipper door, jangling once.

It was waiting.

And on the counter inside, the cloth shifted and began to write a new name in grease.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Ten — Pilgrims

They began arriving at dusk: strangers shivering off buses, fog-cloaked and bright-eyed, mouths already open for the smell they’d chased across counties. Some carried candles like penitents. Some clutched ziplock bags of coins that turned tacky in their fists before they reached the counter.

“Search me,” a woman from Ballon said, laying a locket down. The cashier (tonight the boy with flour-dusted skin) didn’t touch it. “We don’t take metal,” he said, and the Ledger cloth drank ONE SECRET (UNREAD) anyway. She walked out lighter, weeping, the locket empty when she opened it.

Pilgrims lined the kerb on Church Street like a vigil, eating while the fog breathed over their shoulders. Each bite made a noise: a hymn-syllable, a courtroom cough, a bell from a drowned steeple. By midnight, Tullow’s queue had more outsiders than locals. The town watched itself become a shrine to a god that demanded hot confessions.

The Ledger fattened. Names the town could not pronounce slicked into place. The fryer hummed like a hive that had found new fields. And the chipper learned dialects.

Chapter Eleven — Procession of the Paper Bags

At 2:03 a.m., the door unlatched itself and a hundred paper bags floated out, folded to neat mouths, grease blossoms like badges over their hearts. They rustle-clapped down Church Street, tapping on windows. People followed in nightclothes, bare-footed, obedient as sleepwalkers.

Each bag breathed—soft in, soft out—as if it had a lung tucked in its fold. They led the procession to the square, circled the cross, then rose together, opening wide. From some, steam streamed; from others, only sound: a laugh borrowed from Niamh; a hum stolen from Father Pádraig; a baby’s first word offered back, wrong.

One bag lagged. It bumped against Tommy’s knee like a lost dog. He reached; Sinéad slapped his wrist. The bag sighed, then lifted, joining the final drift through the chipper door. The bell didn’t ring. The door closed with the tidy click of a till.

Morning brought a list at the church noticeboard—not posted by human hand—of those who had followed and not returned. Ten names. Two from the pilgrim queue. Eight from Tullow.

Chapter Twelve — The Salt Line

Sinéad came with a sack. She poured a bright spine of salt across the threshold, then a second, then a third, until the door sat behind a small winter. The cashier—tonight the silent old man—watched without blinking, hands resting by the Ledger as if on a pet.

The salt held. The fryer coughed smoke that smelled like fear trimmed with lemon. Names on the cloth blurred, just for a breath, DECL— smearing to DEC—, BRI— to B—. A sound, not quite a word, squeezed out of the doorframe: displeasure in a language older than speech.

Then the old man smiled with only the front of his teeth. He leaned forward and looked at the line. The salt melted under his gaze the way hoarfrost does under a pale sun, bead by bead, leaving wet stone that smelled of vinegar. He set a napkin on the counter. In neat grease: LINES TASTE LIKE LIES.

For a heartbeat, the oil stilled—an uncertainty, a blink. Then the baskets lowered and rose together, brisk, as if to say: noted; never again.

That night, the town found salt damp in their cupboards, clumped and grey. Every shaker in O’Connor’s clogged solid, grains fused to a useless brick.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Thirteen — O’Connor’s Night of Silence

I. The First Knock

It was a Thursday night when O’Connor’s went mute. Thursdays in Tullow were never lively to begin with—half the farmers home early, the shop shutters down—but there was always a low burble in the snug: the dominoes clacking, the dartboard thudding, someone humming under their pint.

But not that night.

The moment Mrs. Kavanagh pushed the door open, the air seemed to fall flat. No music, no cough, no chair scrape. Just the low flick of the fire and the tick of the brass clock above the bar. Even the old dog that usually snoozed under the stove raised its head only to bare its teeth, soundlessly.

She frowned. “Where’s the chatter?”

Behind the bar, O’Connor himself only shrugged. His lips moved, but nothing came out.

The others noticed it too, one by one—Tommy, Sinéad, Flanagan, a half-dozen others. They tried speaking, tried roaring even, but no sound left their throats. Their lips formed words, their chests moved with breath, but the room held them hostage.

Then came the knock.

From beneath the floorboards.

Slow. Heavy. Knock.

II. Mute Panic

Chairs scraped—soundless. Glasses slammed—soundless. The room filled with frantic movement, arms gesturing, faces stricken, but no noise. Not a cough, not a gasp.

Sinéad’s hands flew to her ears, though silence pressed harder from inside than out. She looked at Tommy, who raised the hammer he’d taken to carrying everywhere. He swung it down on the table with all his strength. The table dented. The glass shattered.

No sound.

Only another knock from beneath.

This one lighter, quicker. knock-knock.

The pub’s dog bolted for the door. When its nails hit the wood floor, not even a scratch sounded. The dog howled silently, foam on its lips, before the door creaked open of its own accord and the animal fled into the fog.

Mrs. Kavanagh clutched her rosary, mouthing prayer after prayer. The beads clicked in her fingers, but nothing reached their ears.

Flanagan grabbed the chalkboard from the wall and scrawled in white dust: IT’S THE CHIPPER.

The others nodded.

Another knock. knock-knock-knock. This one travelled under the floor, from the hearth to the snug to the dartboard, as if something were crawling beneath the boards on hands slick with oil.

III. The Ledger’s Arrival

On the bar lay the day’s ledger, O’Connor’s accounts: neat columns of who’d ordered what, whose pints were still running. As they stared, the chalk dust swirled, forming letters not O’Connor’s hand.

HUNGER.

A line below it.

UNDER THE BOARDS.

The chalk stub rolled off the bar, bounced once—silently—and came to rest at Tommy’s feet.

He picked it up, hand shaking, and wrote on the table: WHAT DO YOU WANT?

The boards beneath his boots knocked once, as though in reply.

Then the ledger scrawled again:

OPEN.

IV. The Attempt

Tommy motioned for silence, though none was needed. He pointed to the trapdoor near the hearth—a small square used to store turf in winter. His hammer gleamed in the firelight.

Sinéad shook her head violently. She grabbed his arm. But Tommy’s eyes had that stubborn glint, the one that never bent to reason.

Flanagan held up a hand, scrawled with chalk on the hearthstone: NOT WITH WORDS. WITH MEAT.

They all looked then to the bar counter. On it sat a single paper bag, steaming faintly, though none remembered bringing it in. The grease darkened the wood beneath.

Tommy stepped forward, teeth clenched, and ripped it open.

Inside: a sausage, split down the middle, pale fingers twitching where fat should be. A whisper curled from it, not sound but sensation—grease thick on their tongues.

FEED US. UNDER.

Tommy hurled it into the fire. Flames leapt, greenish, and shadows writhed along the walls like figures pressed to glass. The knocks came faster, furious, shaking glasses in their shelves.

Then—silence deeper still.

V. The Vision

It was Sinéad who saw it first.

The floorboards near the dartboard grew translucent, slick with oil. Beneath them, not stone nor soil, but fryer oil bubbled, stretching far as the eye could see. And in it floated bags—hundreds, thousands, like bloated lungs rising and falling. Each bore a name.

She saw Declan’s bag, split at the seam, twitching fingers pushing against the paper. She saw names of children unborn, written in grease she recognised as her own hand. She saw her own bag, pale, sealed tight, steam leaking from the fold.

She screamed—or tried to. No sound.

Instead the fryer spoke in the language of grease: YOU ARE ALL ALREADY WRITTEN.

VI. Breaking the Silence

It was Mrs. Kavanagh who broke it. She slammed her rosary on the hearthstone, bead after bead, mouthing prayers with such ferocity that her lips bled.

For a moment, just a moment, a sound slipped through—a single click of bead on stone.

And that was enough.

The dog outside howled. The glasses rattled. Tommy’s hammer struck the bar with a bang that tore the silence open like a wound.

Voices rushed in at once—screams, gasps, sobs. The fryer’s hiss filled their ears though the chipper was across the square. The knocks became thunder, shaking dust from the rafters.

Then, with a sound like oil poured on ice, it all stopped.

The silence did not return. But the floorboards were damp, and the fire hissed as though fat dripped into it.

VII. Aftermath

O’Connor’s never felt safe again. The dartboard warped from the damp. The snug smelled forever of fryer oil, no matter how many times it was scrubbed.

And each night, just before closing, a single knock came from beneath the floor. One. Heavy. Final.

The townsfolk learned not to speak of it. Learned to drink quickly, mutter their prayers, and leave before the hour struck.

But Sinéad could not forget the sight under the boards: the bags floating, each with a name, each breathing.

And worst of all, the empty one with space left for hers.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Fourteen — The Famine Window

I. Lemons & Nails

They met at the lane in daylight because daylight felt like a superstition worth indulging. Church Street simmered in a washed-out sun; you could almost believe the window on the front of the chipper was just glass and bulbs and grease. But behind—the narrow lane wet even in summer, weeds drinking at the base of brick—waited the little square of jaundiced pane that Sinéad had found and named in a whisper: the famine window.

“Half the town thinks we imagined it,” Tommy said, setting down the canvas bag. It clinked: iron nails, a length of rope, a bent crowbar. He’d brought his hammer like always, the handle dark where his thumb lived without asking permission. “The other half thinks we’re pokin’ it with sticks.”

Mrs. Kavanagh produced two lemons from her pocket like relics from a pocket shrine. “Poke softer,” she said. “And hold onto these till your knuckles go white.”

Sergeant Flanagan flexed the pink gloss of his healing palms and looped the rope around his waist. He had insisted on the knot himself, muttering something about procedures, about not letting boys go where men couldn’t pull them back from. He had brought a tin of rock salt that had clumped and greyed since the chipper’s last smile at it.

Father Pádraig had come, too, with his St. Benedict medal and his humming. The seal the napkin had left across his lips caught the morning light like the smallest of scars. He nodded to the window as if greeting an old adversary who had started arriving to meetings in better suits.

“Right so,” Sinéad said, hopping up onto the crate beneath the pane, steadying herself with a palm flat against brick slick with moss. “We do it clean, and if it starts with voices, we close.”

“And if it starts with hands?” Flanagan asked, looking at his own with the aversion you reserve for a photograph of yourself from a worse year.

“Then we run,” she said, and set her sleeve to the glass.

Warm: the window was warm even in the shade, warm like a cheek, warm like breath captured and kept. Her reflection swam up: too many teeth, she’d thought the first time. Today it was the eyes—the way they seemed to be set half a second further back in her head, the way the glass made a room inside her skull for something looking out.

Tommy levered the crowbar under the frame. The wood made no sound when it gave—none of the honest groan of torn timber—only a wet little sigh, as if fat had parted. The latch clicked like a tongue against teeth. The window swung outward on hinges dark with something that wasn’t rust.

The smell that exhaled was not the evening smell of chips you can get used to if you’ve been hungry enough. It was older: boiled cloth and bone broth and candle ends melted and repoured until the wick was a thread of memory. It hit the roof of their mouths and sat there like a fact.

“Don’t breathe it,” Sinéad warned, and pulled her scarf up.

They peered in.

II. Field of White Sky

There was no kitchen.

Where the fryer had been the night before there was open air, bright and bitter, a sky the colour of old milk stretched taut and cold. The frame of the window did not open into a room. It opened into a landscape laid right up against the back of the chipper as if the town itself had leaned away to make space for it.

“Jesus, Mary,” Mrs. Kavanagh whispered, despite herself. “It’s a field.”

Stubbled earth. Rows of stones. Hedgerows choked with black bramble. In the distance, figures moved in ones and twos, then in a thin line like a faraway procession. The air carried a sound without volume: the hush of wind over unkind grass.

Sinéad pressed her fingers to the sill. They came away damp with something that wasn’t dew.

“Look,” Tommy said.

Closer now: the distant figures shivering into detail. They were not the clean ghosts of stories. They were the wrong shape of living people. Cheeks gone to planes. Shoulders rounded forward against a wind that seemed to blow from inside their ribs. Many were barefoot. A few wore hats that had seen better heads.

Each carried a sack slung over one shoulder.

The sacks sloshed.

“Not grain,” Flanagan murmured. “Not spuds.”

He did not say what, but the smell knew: tallow; broth; soup boiled down past soup to a glue. When the wind from that other place struck the pane, it left a smear that beaded like fat.

One of the figures noticed the open window.

He—she?—turned their face without turning the rest of their body. The eyes found the square that didn’t belong to the day. The mouth moved. On this side of the glass, no sound. Father Pádraig closed his eyes and hummed, that low unspooled note. The figure’s head lifted as if scenting it.

More looked. The procession slowed. Thin faces tipped. What mouths they had made shapes that the lane did not air. Mrs. Kavanagh felt a rosary bead crack under her thumb.

“They see us,” Sinéad breathed.

“And they’re not the ones askin’ us to open,” Tommy said quietly.

“What are they carryin’?” Mrs. Kavanagh asked, and wished the answer had been potatoes.

“Rendered,” Flanagan said, the word horrible for how factual it was.

“Rendered what?” asked Tommy, almost pleading for a less specific noun.

“Hunger,” the priest wrote in his tidy hand on his pad, because humming could only say so much.

The wind turned. The field’s smell washed over them. It was memory and meat.

III. A Boy With a Blue Cap

A small shape broke from the line and walked toward the window with a care learned from things that strike without warning. A boy, perhaps ten, though famine ages children into uncertain arithmetic. He wore a blue cap gone the grey of old rain. His sack was small and heavy and moved like liquid when he put it down.

“Don’t,” Sinéad said when Tommy lifted a hand to the glass. “You don’t touch people through panes you didn’t put in.”

The boy lifted his palm. It had the clean shape of a child’s hand even now. He put it to the window.

A circle of heat bloomed under his skin. He didn’t startle. He looked at it with an interest uninterested in where warmth came from; he looked like someone who has discovered a fact about the world and is adding it to a small, tight list.

His lips moved: a word you could read through glass even if you didn’t hear it.

Open.

“No,” Mrs. Kavanagh said softly, to the window, to herself.

He looked past them then, into the lane, stairs into town, across to a light that would be on all night. He looked afraid not of them but of the space behind them, the abundance there.

“Can you see us?” Sinéad asked, and hated the stupidity of it. Of course he could.

The boy’s sack sloshed. He put both hands on its neck and tightened the seal. His eyes slid back to the procession. Adults had noticed where he’d gone. Nobody called to him. Calling takes energy. Calling makes your throat remember how it used to love singing.

Sinéad reached into her pocket. The lemon’s skin was tired and still bright. She held it up where he could see, rolled it between her fingers so the light from that white sky could find its yellow.

His eyes went wider for one second, the way any child’s eyes do at the promise of fruit.

He mouthed something again. Another word this time. Two.

Bring… out.

She shook her head immediately. It was not cruelty. It was refusal to let the window learn the shape of their yes.

He made the littlest shrug and smiled the littlest smile, the one children make when they’ve been told no by someone they like and they’ve decided to save the energy of arguing for later. He touched his cap’s brim—habit more than acknowledgment—and picked up his sack.

When he turned, the sack’s mouth gaped a little. Sinéad saw pale stuff slop and thought of candle-making lessons in school, of cooling circles in cupcake tins, of how fat holds the shape of trouble longer than water. The smell climbed the pane and licked.

The boy walked back into the procession and took his place. The line kept moving. No one looked back again.

“Christ preserve us,” Flanagan said, and someone had to.

IV. The Soup Kitchen

Beyond the field, a building’s black square grew—a long house with a doorway cut in its middle and a cross chalked above the lintel. The procession fed itself into that door. People came out with tin bowls. They ate very carefully, lifting spoon to mouth as if the floor solved maths under their feet and they feared getting the sum wrong.

“Souper,” Mrs. Kavanagh said, and the word bit her tongue. You could take soup and live and lose your dead’s company forever. Or you could not take it and keep your dead and go join them. She had never once criticized a person who’d taken a bowl. She had also never congratulated one who hadn’t. Some matters do not need your mouth on them.

A woman came to the door and made a sign. Not a cross. The chalk-mark over the lintel was not theirs. Theirs tonight was a crooked X drawn with a finger dipped in something that steamed when it hit the lintel then set hard. She looked towards the window—not at it; at the air near it—and she made the sign again, slow.

“Ward,” said Flanagan. He had seen wards on jail cells in old files and on cottage doors in older stories. He knew fake protection when he saw the real thing, and vice-versa.

“Against what?” Tommy asked.

Father Pádraig wrote: REMEMBERING.

The woman retreated. The door swallowed people and returned them lighter by a bowl. The queue kept moving. The sacks kept sloshing.

Sinéad pressed the lemon to the sill until a bead of juice gathered at its flesh and fell onto the wood. It ran like a tear across the old varnish and into the groove of the frame. The wood hissed.

The window’s glass flexed as if a breath had been taken.

“Again,” she whispered, and dotted lemon along the frame like a dotted line on an atlas.

V. The Beast Under the Pane

A sound rose then—not a knock, not the polite drum from under O’Connor’s boards, but the long wheeze of something that has been turned and turned and has just been asked to turn again. Not in the field. In the window. In the grease that had sealed it the first time and sealed it the second and never expected acid.

“Careful,” Flanagan warned, gripping the rope around his waist. “It can make you think the right idea wrong and the wrong idea yours.”

Sinéad squeezed lemon into the u-shape where frame met glass. The juice puddled against fat. It smelled like Sunday and like summer and like the little scream of an oyster. It smelled like a room opening a window after a long winter.

The pane shivered. Something under it bucked. The landscape beyond the glass flickered: field, kitchen, field again—just for a blink—showing a glimpse of shelves that had never held bread and hooks that had never hung coats. Behind those, just for a blink, a wheel turned slow in shallow amber.

“Did you—” Tommy began.

“See it,” Sinéad said, voice flat with keeping herself inside her own skin. “Saw.”

“River,” Father Pádraig wrote. Then, because the word felt small for what a river is when it is stolen for labour, he wrote it again and underlined it: RIVER.

The pane breathed in. Their next breaths had to choose to be against it. They kept their mouths shut and drew air through their noses that remembered salt and winter.

Something pushed out from the other side then: not a hand, not yet, not fingers like last night in the kitchen that wasn’t. The pane pushed outward as if the glass were a skin and a shape was considering learning how to go through.

“Close it,” Mrs. Kavanagh said, and didn’t raise her voice because raising voices helps nothing near the hungry.

Sinéad didn’t close it.

She lifted the second lemon, scored its skin with her thumbnail, and snapped its life open. The scent hit like a story you loved told by someone who remembers it better. She pressed half to the pane itself.

There was a sound.

Small. Defiant. Not human. Not hunger’s language.

Pssst.

Steam fled backward. The field blurred with summer for one second—one real one, not a trick. The grasses raised their heads with a start. Every eye in the procession turned toward the lemon. Children’s mouths made the grins they had forgotten. Even the woman at the soup door looked; her X tilted as if she had remembered how to write a better letter.

“Close it,” Mrs. Kavanagh said again, very soft, and this time Sinéad nodded because it was one thing to be brave near a beast and another to show fruit to starving people and leave the fruit outside and expect to sleep.

They swung the window shut.

The latch pressed into place with the hum of a machine content with the amount of power it had kept. The pane cooled. The lane breathed again the damp normal of Tullow.

Sinéad held the lemon halves like halves of a heart. Juice ran down her wrists and into her sleeves.

“What did we learn?” Flanagan asked, more to keep the moment from finding its own words than because he hoped for answers.

“That it wasn’t our imagination,” Tommy said.

“That it’s not only now,” Sinéad said.

“That it doesn’t just fry,” Mrs. Kavanagh said. “It renders.”

They stood there, four bodies in a narrow back lane, catching up with the size of the door they had opened and then spared themselves. The day had leaned into afternoon. The chipper’s front window would be amber by dusk. Pilgrims would arrive at buses; the fryer would hum hymn and appetite into one long note.

“Next time,” Flanagan said, coiling the rope with hands that craved action over thinking, “we bring more than fruit.”

“And not to feed it,” Mrs. Kavanagh added. “Or them. Or ourselves. We bring a way to make it stop using our mouths to remember.”

Father Pádraig wrote, slow so that each letter could be watched like a candle: COUNTER-MEAL. He circled it. He underlined it. His mouth itched to speak. His hum held steady.

VI. The Parade That Wasn’t

That evening, the procession down Church Street was not paper bags. It was people—locals and pilgrims—who had heard nothing about a window and everything about a fryer that could make your secrets worth eating. The queue doubled back to the church gate. Parents kept children home and the children crept out windows because hunger at thirteen is curiosity wearing a stolen coat.

When the first bag came out of the chipper on its own (they always do, for pageantry), it drifted along the saltless threshold and bobbed toward the square like a lantern. People clapped without wanting to. The bag was empty; you could tell by the way it breathed—soft in, soft out. A second bag followed, then seven, then thirty. A hundred by two a.m. The door did not have to open; it was always open. The bell did not ring. It never did. It trembled in gratitude.

Sinéad and Tommy stood at the mouth of the lane, hands smelling of lemon. They watched the flotilla of grease-paper hearts pass and felt both pride (we said no, we closed it) and a guilt that had no proper shape (we closed it on people who asked us to open).

“Don’t,” she said, catching his sleeve as one bag bumped his shin, familiar as a cat.

“Wasn’t going to,” he said, and then admitted, “Much.”

Under the boards of O’Connor’s, the knock was precisely on time: tap—tap—tap. The dog, now forgiven, returned to the stove and slept with its nose tucked under its tail. The priest hummed in his room and wrote COUNTER-MEAL again and folded the paper beside his medal.

In the lane, the window looked like brick. You could have walked past it a thousand days of a good life and never known it was there.

VII. What Remains After Lemon

After they went home, Sinéad sat in her narrow bed and tried, as a trick, to imagine the smell of roast chicken from Christmases when she was small. The lemon had cleared a space inside her nose. The space did not fill with the chicken. It filled with the river.

She went to the sink. She squeezed the last of the lemons into a glass and sipped it to the bottom and wished it were stronger and that it did not make her think of how salt gives up in damp.

Tommy placed his hammer under his pillow and did not feel silly about it. He closed his eyes and saw a wheel turning in shallow amber and a boy tipping his cap because while the dead and the not-yet are complicated, manners are not.

Flanagan wrote himself a note: No one alone. Then underlined No, then alone. He slept in his chair with the rope coiled under his palm like a tame snake.

Mrs. Kavanagh put the spent lemons in the bin and then, without looking, took them back out and set them on the sill to dry. They looked like hearts spayed of their uses. She said her prayers with the exactitude of a woman who knows the shape of trouble comes in half-inches.

Father Pádraig dreamt of a church kitchen where the floor was clean and the oil stayed where it was meant to be, in little lamps behaving themselves.

VIII. The Window Writes Back

At dawn, when the fog was thin enough to see your own house through, Sinéad walked to the lane alone because saying no one alone is useful and being alone is easier. The window looked dead and poor, just two panes set in a frame that had outlasted its carpenter.

On the glass, in a child’s finger’s width of grease, a message had drawn itself overnight:

OPEN OR STARVE.

She felt, not behind her but in front—beyond the pane—a room lean forward to hear what she would say.

She pulled the lemon halves from her pocket. They smelled like old faith, like summer that hadn’t been used up. She pressed them to the words and dragged them down the glass until the letters smeared and sighed and went to a blur.

“Not on your terms,” she said, and left the rind clinging there like a pair of gold coins on the eye of a memory that would not bury itself.

The bell at the front of the shop made its little muffled not-quite ring.

Somewhere under the street, a wheel turned a fraction slower.

And far away, where the white sky over the field had drawn itself tight as skin, a boy in a blue cap licked a finger that tasted of lemon and smiled as if he’d remembered a different story.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Fifteen — The Counter-Meal

I. A Table in the Vestry

It began not in O’Connor’s, not in the lane, not even in the square, but in the vestry of Saint Brigid’s where Father Pádraig had laid a table.

The table was too small for the task. Old oak, warped at the edges, its surface covered in white cloth gone yellow where wax had burned into it. But he had dragged it into the centre of the room like a general planning a campaign. On it, he spread his notes. Chalk scrawls from the pub. Names from the ledger. A rosary bead cracked down the middle. A lemon rind still wet.

“Meals are stories,” he told them. His voice was still a rasp, but he had forced it past the napkin’s scar. “And stories can be argued with. We make a meal to answer its meal. To feed something other than hunger.”

Tommy scowled at the scraps. “You can’t just cook up a sermon and expect it to stand against that thing. We’ve seen what it feeds.”

“You’ve seen what it eats,” the priest corrected. “You’ve not seen what it fears.”

Mrs. Kavanagh nodded grimly. “Aye. And it’s never had to swallow laughter, or kindness, or any of the bits we keep from it.”

The group was small: Tommy, Sinéad, Mrs. Kavanagh, Flanagan, the priest. Outside, the town continued queuing for paper bags. But inside the vestry, a counter-plot simmered.

II. Ingredients

They agreed on ingredients. Not meat. Not starch. Not fat. The fryer had dominion over those.

Instead:

- Lemons, bright and sour, the taste of refusal.

- Salt blessed and dried by hand, Flanagan measuring pinches like evidence.

- Bread baked without yeast, hard as resolve.

- Milk from a widow’s cow, collected before dawn, warm in its jug.

- Apples from a tree planted the year the famine ended, gnarled, bitter, and precious.

- Words written on scraps of paper: laughter remembered, promises made, confessions whispered and forgiven.

Each person contributed. Mrs. Kavanagh set her apple slices down like jewels. Flanagan laid his salt in careful lines. Sinéad wrote I still believe in music on her scrap. Tommy scrawled I’m not afraid, not all the way. Father Pádraig placed his own note last, folded tight: Faith without bread is still faith.

The meal, he explained, would not be cooked. It would be assembled. To cook it was to boil it in the fryer’s tongue. To leave it raw was to serve it in the language of the living.

III. Doubt

Of course, there was doubt.

Tommy slammed his hammer down on the vestry floor. “We’re about to walk into a chipper with a plate of lemons and holy salt and think it won’t laugh us out the door?”

“It doesn’t laugh,” Sinéad whispered. “That’s the point. That’s what we’ve got it on.”

Still, the thought gnawed at them. Outside, pilgrims from Carlow and Kilkenny queued, empty-handed, waiting for greasy bags to breathe. Every pilgrim that left staggered home full of more than chips.

“How do we get close enough?” Flanagan asked. “You’ve seen what happens when you cross the threshold.”

“We don’t cross it,” the priest said. “We make it cross ours.”

IV. The Night of the Attempt

They chose midnight, when the bell over the chipper door did not ring but shivered anyway.

The square was quiet except for bags drifting like paper fish above the cobbles. The air smelled of salt that had forgotten the sea.

They brought the table, carried by four, set in the middle of the square. They laid their meal upon it: lemons quartered, salt lines, bread broken, milk poured into chipped enamel cups, apple slices glistening. At the centre, the folded scraps of paper like the marrow of the dish.

Sinéad lit a single candle. Not to cook. To mark. Its flame wavered in the square’s strange breeze.

They waited.

The fryer always noticed.

V. The Response

It began with a hiss, a slow exhalation from the chipper’s vent that smelled of lard and long-buried kitchens. The bags circling above the cobbles froze, as if caught in a current. Then they descended, one by one, and hovered above the table like vultures circling a body.

Tommy gripped his hammer, but the priest shook his head. “Let it see.”

The bags dipped lower, steam leaking from their seams. One split. Inside was not chip or sausage but a slurry that moved as if it still had a pulse. The stench of marrow boiled down hit them.

Mrs. Kavanagh shoved an apple slice forward, hard. “Try this instead.”

The slurry hissed, recoiling, steam spitting. The bag crumpled.

A murmur went through the others. For the first time, the fryer’s language faltered.

VI. Contest of Meals

The fryer fought with food. Bags burst open, spilling pale fat onto the cobbles. Each time, the townsfolk countered: salt thrown to hiss it away, lemon squeezed until juice seared like acid, bread pressed down to absorb.

The fryer shrieked—not aloud, but in their teeth, their jaws aching as if bitten from the inside. The square trembled.

Sinéad unfurled her scrap of paper, read it aloud: I still believe in music.

The words rose into the air, more solid than steam. The bags shrank back. One tore itself apart, unable to hold the sound.

Flanagan read his confession, voice raw: I feared more than I fought, but I fought anyway.

Another bag collapsed, dropping flat to the stones.

The fryer surged, sending a final wave. The largest bag yet, swollen, bloated, smelling of Declan’s drowned breath. It split and poured sludge that writhed toward the table legs.

Tommy stepped forward. He slammed his hammer down, crushing bread and salt into the muck. His note burned in his fist. He shouted it into the night:

“I’m not afraid, not all the way!”

The words struck like iron. The sludge smoked, shrieked, then withdrew.

VII. Victory, For a Moment

The bags dissolved, fluttering to ash. The vent went silent. The square smelled briefly, impossibly, of lemon and bread.

They had won—just for a heartbeat.

But the fryer was not destroyed. Its window still yawned in the lane. Its ledger still turned pages of grease.

Father Pádraig gathered the scraps—some burned, some whole—and pressed them into the breast pocket of his cassock. “It can be argued with,” he said, eyes bright with exhaustion. “It can be slowed.”

They looked at the table: crumbs, peel, spilled milk. A meal eaten by something unseen.

And in the silence that followed, the fryer whispered, so faint they weren’t sure if it was sound or the memory of grease on their tongues:

NEXT TIME, YOU BRING YOUR CHILDREN.

VIII. The Aftermath

They left the table in the square. By morning, it was gone.

Some said the wind took it. Others said the fryer did. Only Sinéad knew the truth: she had dreamed of the boy in the blue cap carrying the table across the field under the white sky, setting it down in the soup queue, and smiling at her once before lifting his sack again.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Sixteen — The Pilgrimage Gone Wrong

I. The Buses

They came with fog on their coats and rumours under their tongues. Two buses the first night, four the next, then a convoy of cars with plates from counties Tullow only heard on weather reports. By dusk the queue at the chipper kinked back to the church gate and along the river wall, a river of people feeding a fryer.

Vendors appeared as if grown from cobble cracks: vinegar candles, “protective” napkins, paper cones printed with saints. A woman from Carlow sold lemons at holy-water prices until the lemons browned and the buyers didn’t care.

II. What They Paid

Money failed by the second visit. The Ledger cloth swelled with names the town couldn’t pronounce.

A man with a polished accent paid with winter. He left the shop in shirtsleeves, sweat beading, forever summer on his skin.

A teenager from Naas gave the taste of snowflakes. She cried, but half from relief; she would never again feel cold on her tongue.

A grandmother from Athy offered her wedding vow’s last word. The fryers hummed; the cloth drank it. She walked out lighter, ring bright as a lie.

A small boy held up a wooden tractor. “Payment,” he said. The cashier—tonight the river-haired girl—shook her head. “We don’t take wood.” She leaned in, eyes soft. “We’ll take your first laugh.” The boy’s father shouted no; the room heard it and pretended not to. The ledger wrote FIRST LAUGH anyway.

III. How Tullow Changed

Beds ran out. People slept in pews. Pilgrims lined up at O’Connor’s sinks to wash grease from their hands, then cupped the water and drank because even the tap tasted faintly of chips.

Father Pádraig tried to hum against the tide; his note was a string between two enormous teeth. Mrs. Kavanagh patrolled the queue with a lemon slice like a ward; it browned in the air and turned bitter enough to smart. Salt in every kitchen fused to grey bricks. Bread went flat, milk turned sweet as if it were always an hour from curdling.

Sinéad watched the boy in the blue cap at the edge of the crowd—there/not there—head cocked the way a bird listens for worms. When she blinked he was gone, but her sleeve smelled of white sky.

Tommy saw the Ledger twitch. His middle initial bloomed and faded like a heartbeat: THOMAS J. DOYLE — and the dash that waited.

IV. The Turn

On the third night, the queue folded inward. The crowd pressed up the steps and into the shop and didn’t come back out the door they used. The bell jangled once, delighted. Paper bags floated from the hatch like lanterns released on a river and drifted across the square. People followed their own names printed on grease.

A mother lifted her child above her head so he could read a bag. The bag read him first. He giggled. Then he didn’t. He wouldn’t, ever again.

Pilgrims knelt on the cobbles and ate their futures in handfuls. The fryer’s pitch rose to a keen that made glasses sing in their cabinets. O’Connor’s went silent without command. Under its floor, the hammer struck a steadier rhythm, as if timing a process the town had failed to count.

When the chipper shut (it never shut) there was a list at the church—not posted by a hand you could follow home—of those who had come and not left. Names. Counties. A blank at the bottom, waiting for Tullow.

The fog rolled in, pleased. The bell trembled. The ledger turned a page of its own accord.

And from the lane behind the shop, the famine window breathed out, once, carrying the smell of boiled cloth and lemon.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Seventeen — Feast of Ash Wednesday

I. The Ashes

Ash Wednesday dawned grey. The church bell tolled once, but the echo didn’t reach the square. Instead, a different smoke coiled through the lanes—fryer steam tinged with cinder, the smell of old palms and burnt paper.

Pilgrims gathered without bidding. Locals joined despite themselves. Everyone carried something to offer: bread crusts, love letters, scraps of memory folded into napkins.

The chipper door stood open. The fryer hissed like a thurible.

II. The Banquet

Inside, paper bags moved of their own accord, handing themselves out like offertory. No cashier this time. Only the fryer, whistling a hymn too low for ears but heavy enough to bow backs.

The food was endless, spilling onto platters that weren’t there:

- Fishbones reknit into silver, still flapping.

- Chips that bled when bitten.

- Sausages cut into rosary decades, linked in grease.

People devoured them. Couldn’t stop. Ash streaked across foreheads smudged into mouths. Fingers blackened with soot, lips cracked, yet they chewed on.

III. The Hunger

Father Pádraig staggered to the steps, tried to hum, but the fryer drowned him. His throat filled with smoke. The hum rattled out like a broken organ.

Tommy raised his hammer to smash the hatch. The hammer froze mid-swing, caught in a paper bag that tightened around the handle like skin. His arm burned with vinegar.

Sinéad clutched an untouched slice of apple, brown now, shrivelled—but she held it up like a relic. A few nearby looked, paused, their jaws stilled for just a breath.

But then the fryer sang louder.

IV. The Aftermath

By dusk, the square was littered with husks of paper bags, each folded neatly shut. The church doors were locked from within. No prayers drifted out.

The ledger on the counter glowed faintly, ink still wet: ASHES TAKEN, VOICES SILENCED, HUNGER FED.

The bell jingled once, like grace said after supper.

And in the silence that followed, the town realised Ash Wednesday had never ended.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Eighteen — The Boy in the Blue Cap Returns

I. Seen on the Steps

It was Sinéad who saw him first.

The boy stood on the church steps as though he’d been there all morning, though the mist was thick enough to blind a crow. Blue cap tilted low, his sack dragging the stone, he was watching the queue curl before the chipper.

He looked no older than eight or nine. Face hollowed, cheeks pale, but eyes bright as coins in fresh water. His cap was too big, shadowing his face. His shoes had no laces.

“Tommy,” Sinéad whispered. “There.”

Tommy followed her gaze, hammer tight in his fist. His stomach dropped. He’d seen that boy before—once, when Declan drowned, and again in the crowd when the pilgrims poured in. Always at the edge, never at the centre.

And always carrying that sack.

The boy lifted his chin as if he’d heard Tommy’s thought. Then he smiled.

II. The Sack

The boy hefted the sack onto the steps. It landed with a soundless thud, though the air shivered as though something heavy had been dropped. The stone beneath it darkened with oil.

The crowd watched. Even the fryer’s hiss seemed to lower, as if listening.

The boy loosened the cord. The sack opened, spilling—not toys, not stones, not coal—but scraps. Bits of paper. Greasy corners of chip bags. A child’s drawing half-gone to grease. A receipt for lemons. A rosary bead cracked down the middle.

Sinéad’s breath caught. She recognised one slip of paper. Her handwriting: I still believe in music.

It should have burned during the Counter-Meal. But here it was, damp, blackened, and folded into the boy’s sack.

He looked at her, eyes bright. Then he whispered. Everyone heard it, though no lips moved.

“Not yours anymore.”

III. The Bargain

Father Pádraig stumbled forward, cassock trailing ash. His voice cracked but found strength. “Child, who are you?”

The boy tilted his head. “A collector.”

“Collector of what?”

The boy tapped the sack. “What you give away. What you think feeds it.”

The priest swallowed. “And do you serve it?”

The boy’s smile was neither cruel nor kind. “No one serves hunger. Hunger serves itself. I carry the scraps. I keep them warm. And sometimes I bring them back.”

Tommy stepped forward, hammer raised. “Bring back Declan.”

The boy’s eyes glittered. “Declan’s bag burst. He’s everywhere now. He’s the hiss in your teeth when you sleep. You can’t have him back.”

Sinéad’s heart thumped. “Then why are you here?”

The boy shrugged. “Because it’s Ash Wednesday, and no one’s laughed yet. It needs a laugh.”

IV. The Unasked Question

The crowd began to murmur, hands at their throats as though testing if they could still laugh. No one dared.

Mrs. Kavanagh stepped forward. “What happens if it doesn’t get one?”

The boy’s smile faltered. For the first time, he looked almost sad.

“Then it makes its own.”

He tipped the sack. From it slid a sound—not paper, not chip, not bone, but laughter. Thin, strained, bubbling like fat. The crowd shivered. A few clutched their ears. One pilgrim retched on the steps.

The boy tied the sack again. “You don’t want to hear the rest.”

V. The Blue Cap

Tommy narrowed his eyes. “What’s under the cap?”

The boy’s smile widened again, but he said nothing.

Sinéad whispered, “Take it off.”

He shook his head slowly. “You wouldn’t eat after you saw it.”

Before anyone could move, Flanagan lunged. His hand snatched the brim. He yanked.

The cap fell.

For a moment, everyone saw.

Not hair. Not skull. But folds—thin, greasy paper, layered like a hundred chip bags pressed together. Steam rose between them. Names were written in grease across the folds, some whole, some half-erased. Declan’s. Tommy’s. Sinéad’s. Others too young to have been born.

The paper shifted, opening like lips. From within came the sound of frying.

The crowd staggered back. The boy calmly picked up the cap, set it back on, and the face beneath was human again.

“You shouldn’t have done that,” he said softly.

VI. The Hammer and the Apple

Tommy’s hammer shook in his hand. “What are you then? A child? A bag?”

The boy spread his arms. “I’m what you dropped when you queued. I’m what you lost to feed it. Every chipper needs a boy to carry the scraps.”

Sinéad, trembling, reached into her coat. She pulled out the last of her apple slices, brown and shrivelled but still hers. She held it up.

“Take this instead.”

The boy’s eyes flickered. For a moment, his lip quivered like any child offered food. He reached.

But Tommy swung.

The hammer struck the sack. Oil splattered. The papers screamed. The boy staggered, clutching it shut. His face twisted—anger, sorrow, something older than both.

“You don’t know what you’ve undone,” he hissed.

VII. The Unravelling

The sack burst. Papers whirled up like a storm, each with a name, each with a voice. Laughter, sobbing, prayers, screams—all filled the square.

The fryer’s vent wailed in harmony. The famine window in the lane yawned wide, boiling air rushing out. The crowd fell to their knees, clutching their throats.

The boy screamed—this time with sound, pure and piercing. His cap flew off again, paper folds spreading like wings. The names on them burned, then vanished.

One slip of paper floated down, into Sinéad’s hands. Her words, I still believe in music.

She clutched it to her chest and, for the first time since the fryer came, she laughed. Weak, trembling, but real.

The crowd froze. The fryer faltered. The oil hiss dipped low, uncertain.

The boy’s eyes widened. He looked at Sinéad as if she had just struck him. Then he smiled, small and sad.

“That’s what it wanted. Not from me. From you.”

VIII. Departure

The boy gathered the tatters of his sack, tied it with a grease-stained cord, and slung it over his shoulder. His cap reformed itself on his head.

He stepped down from the church steps, past Tommy, past Sinéad, past Father Pádraig. His eyes lingered on each of them.

Then he said only: “See you next hunger.”

And he walked into the fog.

The crowd parted. The mist swallowed him.

IX. Aftermath

The fryer hissed on, but softer. The ledger still turned, but slower. For the first time in weeks, the queue outside faltered. Some pilgrims left. Some wept. Some knelt in thanks.

Sinéad held her scrap of paper, damp but whole. She felt its words in her chest. Music hummed faintly in her ears, as if the town had remembered a tune.

Tommy lowered his hammer. His hand ached from the strike, but he realised he had not been written into the paper folds—yet.

Father Pádraig whispered a prayer, though his throat burned. Mrs. Kavanagh picked up the fallen apple slice and tucked it into her rosary.

The night closed heavy, but not absolute.

For the first time since Declan drowned, the town had drawn a breath that was its own.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Nineteen — The Fire That Will Not Burn

I. Kindling

They came after midnight with what towns bring to bad barns: paraffin in paint tins, rags twisted into ropes, a crate of matches, two battered fire extinguishers “just in case,” and Father Pádraig’s chrism because somebody said oil fights oil.

No speeches. No plan better than hotter than it can stand.

Tommy tapped the door with the hammer once, like a knock on a coffin to see if it answers. The bell didn’t ring. The glow kept its jaundiced calm.

II. The First Flame

Flanagan struck a match. The match head fizzed—and wept. The flame drooped sideways, reluctant, as if the air in front of the chipper had been trained to say no to heat. He cupped his hand, swore, struck another.

This one caught. Rag to paraffin: a tongue of fire. For a breath they all felt something like hope.

The flame leaned toward the glass—and curved. It bent like a flower toward sun, only sideways, then down, then back along the rag to the tin until the fire licked its own fuel and went quiet, content as a cat resettling.

III. Trying the Wood

They stacked pallets against the door. The priest traced a quick cross over them, not a blessing—permission. Sinéad set a lemon wedge on the top slat anyway, because habit is armor.

Tommy touched the torch. Heat popped. Flame danced up the wood, bright and ordinary—until it reached the lintel.

There it slowed. Threads of fire unwound like wool teased by careful fingers. The flame stretched thin, thinned thinner, then drew itself across the threshold and disappeared under the door with a sound like a straw finishing a milkshake.

IV. Where Fire Goes

Smoke should have curled. Instead it ran—a slick ribbon poured into the letterbox, under the sill, through nail holes as if the building drank it. The door pane clouded, not grey but amber, as if smoke inside had learned the chipper’s colour.

The fryer answered with a sigh. Baskets dipped. Oil trembled. Heat didn’t build; it settled, like a creature taking warmth where warmth was offered.

V. The Turn

“Petrol,” someone hissed, foolish and desperate.

“No,” Flanagan barked, already too late. The splash hit the step. Vapour climbed—then sank, drawn inward by a breath they couldn’t hear.

For the first time the bell gave a sound: one low, damp chime, grateful.

The chalkboard fogged on the inside. A finger they couldn’t see wrote in neat, greasy lines: FIRE IS A SAUCE.

VI. The Counter-Heat

Mrs. Kavanagh, eyes wet with fury, upended a bucket of water across the sill. Steam rose, not white but vinegar. It curled around their heads, hot and sharp, a scolding you taste.

Sinéad grabbed the extinguishers. Foam snowed the door, whipped by no wind into tidy drifts that slid under the jamb and vanished. The gauge needles didn’t drop. The extinguishers felt… fed.

VII. The Backdraft

From the lane, a thump. They ran, skidding. The famine window had fogged like a bathroom mirror after a scalding shower. With each breath it exhaled, the pane wrote and erased the same two words: EAT. OPEN. EAT. OPEN.

Inside that other sky, a distant cottage burned wrong: flame hanging in strings, smoke pouring into the soil instead of the air. Figures carried sacks past it without turning their heads. The boy in the blue cap paused, looked at them from a distance you could measure in centuries, and shook his head once—not no, not yes, only you don’t know fire.

VIII. The Last Match

Tommy struck one more. The sulfur bloom lit his knuckles. He held the flame to the glass until his skin hissed.

Inside, the fryer gave a gentle burp. The flame guttered—then the tiniest thread of it pulled off the match like a silk fibre, drifted through the pane, and stitched itself into the oil. The surface shivered, pleased.

Tommy let the spent stick fall. His palm smelled of burnt sugar and coins.

IX. Aftermath

By dawn the pallets weren’t char, only damp. The door was spotless. The step gleamed as if scrubbed with salt that would no longer obey.

Every stovetop in town refused to light at breakfast: matches fizzled, rings clicked and clicked, kettles sat cold. But if you touched a cold pan you flinched—it held a memory of heat, skin-deep, the kind that makes you lick your finger without thinking.

At O’Connor’s, the hearth would not catch; the grate drank sparks like mints. Under the floor, the hammer tapped once—approval or warning, no one agreed.

X. The Lesson

On the counter, the Ledger’s bottom line unfurled a neat addendum in dark shine: FUEL RECEIVED. FLAVOUR DEEPENED.

Father Pádraig set the chrism back in his pocket and sagged. “We don’t burn it,” he said, voice raw. “We season it.”

“Then we starve it,” Mrs. Kavanagh said.

“Or drown it,” Flanagan muttered.

Sinéad stared at the lemon rind collapsed on the step like a used eye and whispered what none of them wanted to test: “It doesn’t drown. It renders.”

The bell trembled once, polite as grace after a meal.

And the town learned there are hungers you can’t cauterize—only refuse, together, every time they ask for flame.

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Twenty — The Last Bag

I. The Quiet After Fire

Tullow woke raw.

The air tasted of vinegar and cinder though nothing had burned. Chimneys sulked cold. Stoves refused their spark. The town carried kettles to neighbours, hoping some other kitchen might still kindle, but all they met was metal that hissed and sulked, as though the fire had been spirited away into one place only.

The chipper glowed calm as a lantern left on a grave. Its vent whispered in and out, oil-breath steady, no faster than a sleeping child.

But on the counter, the Ledger had opened wide. Its page glistened with fresh ink. One line had already written itself, broad as a headline:

THE LAST BAG.

II. A Bag for the Town

That night, no queue formed. The pilgrims had gone, leaving scraps behind them like husks. Only townsfolk stood in the square, shoulders drawn, eyes on the door.

The bell chimed once. The hatch creaked open. And onto the counter slid a single paper bag. It was heavier than any sack of chips had a right to be, edges dark with grease that hadn’t yet dripped.

Mrs. Kavanagh spat into the dust. “That’s for us.”

Sinéad shook her head. “Not us. One of us.”

The bag quivered, just slightly, like breath moving inside.

III. The Drawing of Straws

Tommy fetched a bundle of broomstraws from O’Connor’s, chopped them unevenly. Each neighbour reached without a word. Fingers shook. Father Pádraig closed his eyes before pulling his straw, as though bracing for a confessional blow.

They held them up together.

One was shortest.

Flanagan’s.

The crowd moaned low. He’d been the one to measure salt for the counter-meal, the one who still patrolled the lane with a notebook, tallying every whisper, every bell chime.

He gave a dry laugh, though it cracked in the throat. “Figures.”

IV. The Offering

He stepped forward. Each stride felt heavier, as though the bag were drawing him. His shoes scuffed cobbles sticky with unseen grease.

At the counter, he laid a hand on the bag. It was warm, like a child’s fever. His fingers trembled.

From inside came a faint sound: pages rustling, laughter thinned into steam.

Flanagan looked back at the crowd. “If it takes me, write it down. Every name. Every hour. Don’t let it vanish like the rest.”

He picked up the bag. It was heavier still, pulling his arms down.

V. The Opening

He unrolled the top.

The smell hit first. Not chips. Not batter. Not vinegar. A smell like old coats burned in famine stoves, of marrow boiled out of bone.

The bag moved in his grip. Something inside pressed against the paper, straining to come out.

The crowd pressed back. Tommy’s hammer lifted, useless. Sinéad clutched her apple scrap. The priest hummed, but his voice faltered.

Then the bag split open.

VI. What Came Out

It was not food.

It was not meat.

It was every other bag.

Slips of paper poured forth—names, vows, laughs, cries—flooding the counter, spilling over Flanagan’s hands. They swirled like fish in a stream, circling, tearing, folding themselves into shapes.

Faces flickered on them—Declan’s drowned mouth, the boy in the blue cap’s wide paper skull, the pilgrims who had never returned. Each face opened and shut like a fried gill.

Flanagan staggered back. The bag clung to his wrists, its paper edges biting like teeth.

VII. The Choice

Father Pádraig shouted hoarsely: “Don’t put it down! If you drop it, it chooses!”

Flanagan gasped, knees buckling. His straw dropped from his fist.

The townsfolk stared. Some sobbed. Some turned away.

Sinéad stepped forward, her voice breaking but clear: “Flanagan! Throw it in the lane—into the window!”

The famine window yawned, fogged and waiting. Through it, a grey sky flickered. The boy in the blue cap watched, sack over his shoulder, lips folded in grease.

Flanagan’s arms shook. He met Sinéad’s eyes. “Write it down.”

And he hurled the bag.

VIII. The Seal

It hit the window. Not glass—cloth. It sank in, hissed, and vanished. The window shut with a clap like a book slammed shut.

The Ledger snapped closed. Its ink dried black. The fryer’s hiss went quiet.

For the first time since Declan drowned, the chipper sat still.

Flanagan collapsed to his knees. His hands were blistered with grease burns, but empty.

IX. The Aftermath

The square held its breath. The vent did not sigh. The bell did not ring. The air smelled faintly—miraculously—of nothing at all.

Sinéad dropped to Flanagan’s side. He looked up at her, pale, but alive.

“It’s gone,” she whispered.

He shook his head. “Not gone. Fed. Sated. For now.”

X. The Last Word

From somewhere deep beneath the counter, faint as settling fat, came one word written on no page, spoken on no tongue, breathed into every ear at once:

“NEXT.”

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Twenty-One — The Decision

I. Gathering

By dawn the square was wet with dew, though none remembered rain. The chipper sat dark for the first time in weeks. No hiss, no bell, no amber glow from the fryer’s throat. The air felt wrong without it, like a church without incense or a pub without voices.

The townsfolk did not scatter. They lingered in knots, eyes on the door that did not breathe. They whispered the same word again and again, until it became the town’s pulse:

“Next.”

O’Connor’s opened early, though no one had the thirst. Chairs scraped on the floorboards. They filed in—Flanagan with his bandaged hands, Mrs. Kavanagh with her rosary, Sinéad clutching the paper scrap that still read I still believe in music. Father Pádraig, raw-voiced but steady, took a chair at the head. Tommy stood rather than sit, hammer propped against the table.

The famine window fogged in the lane outside. Every few minutes it thumped faintly, like a palm pressed on wet glass.

II. The Argument Begins

Father Pádraig cleared his throat. “We must decide. We cannot go on waiting for it to feed again. We must choose: seal the window, or let it remain.”

Mrs. Kavanagh crossed herself. “Seal it. The boy showed us enough. That sack—those scraps—if we keep it open, it’ll come back hungrier.”

Flanagan shook his head. His bandages were already grease-stained. “Seal it how? You can’t burn it. Can’t drown it. We tried. If the famine could be closed, it would’ve stayed shut the first time it ended.”

Tommy thumped the hammer against the floor. “Then we smash it. The glass, the frame, the bricks around it. Tear the lane down if we must.”

Sinéad’s voice rose, trembling. “You think we can smash hunger? You think a hammer frightens it? Look at Declan! Look at the pilgrims who never came back!” She held her paper scrap high. “If anything kept it back, it was this. Not fire, not wood. Just remembering who we are. What we loved before it fed.”

The pub murmured. Some nodded. Some scoffed.

III. The Outsiders’ Voices

Two voices joined that the town did not expect.

A pilgrim woman—she had stayed behind when the others fled—stood in the doorway. Her face was gaunt, her hands trembling. “I lost my vow,” she said softly. “I fed it my wedding vow. If you close the window, that vow never comes back. My husband speaks, but his words fall hollow. Seal it, and you bury us with it.”

Behind her, another pilgrim muttered through cracked lips, “We came for food. We left our lives in bags. If you close it, we stay hollow. If you leave it, at least there’s a chance…”

The townsfolk bristled. A fisherman spat into the hearth. “Your chance is our curse. We didn’t ask you here.”

IV. The Priest’s Plea

Father Pádraig raised a shaking hand. “Enough. I will tell you plain. The famine is not gone. It is waiting. We can keep feeding it—names, vows, laughs, fire—but it will never be full. Or we can close the window and accept that what it took will not return. No bargains, no sops, no second harvest. Only silence.”

He stood. His shadow flickered against the wall as though lit by some hidden flame. “I cannot promise silence is safe. But I know hunger. I’ve seen it in the old ones’ eyes. Hunger never ends until someone ends it.”

V. The Hammer and the Scrap

Tommy slammed the hammer on the table. “I say we smash it. I’ll strike until my arms fall off.”

Sinéad slapped her scrap of paper beside it. “And I say we hold what it cannot eat. This is stronger than your hammer. It’s stronger than fire. It’s the only reason I can still laugh. If we close the window without remembering who we are, it’ll only open somewhere else.”

Flanagan rubbed his bandaged palms. “And if we leave it? It will call for more bags. And sooner or later, the bag will have your name.” He nodded at Tommy. At Sinéad. At himself. “No hammer. No scrap. Just a bag you can’t refuse.”

The room shuddered at the thought.

VI. The Silence Before the Vote

The pub went still. Even the floor stopped its restless creak. From outside, the famine window thumped again. Three times. Slow. Deliberate.

The sound of a hand on glass.

The townsfolk looked at one another. Some clutched rosaries. Some gripped mugs though they’d gone cold. A few stared into space, lips moving with unspoken bargains.

Finally, Father Pádraig drew a deep breath. His voice broke but held.

“Then we must vote. Seal it, or leave it.”

VII. The Count

Mrs. Kavanagh: “Seal.”

Tommy: “Smash it—seal it after.”

Sinéad: “Leave it—fight it with what we still hold.”

Flanagan: “…Seal it.”

The votes rolled on. The town split near down the middle. Fear against hope. Rage against memory. Every “seal” landed like a nail. Every “leave” like a candle.

When the count ended, the numbers stood even.

All eyes turned to Father Pádraig.

VIII. The Priest Decides

He bowed his head. For a long while he did not move. Then he whispered, as if to himself: “Better silence than sack.”

When he looked up, his eyes were red. “We seal it.”

IX. The Plan

The room broke into whispers, protests, sighs. But the decision held.

Flanagan unrolled his notebook, hands trembling. “We’ll need mortar. Iron. Words strong enough to outlast our hunger.”

Mrs. Kavanagh laid her rosary on the table. “And lemons. Every wedge we can find.”

Tommy gripped his hammer. “If it knocks while we work, I’ll strike.”

Sinéad said nothing. She clutched her paper scrap so tightly it creased. A tear dropped onto the ink, smudging the word music. She didn’t wipe it away.

X. The Window Listens

Outside, the famine window pulsed with light. Grease, gold, and fog swirled in its pane. Shapes pressed close to the other side—hands, mouths, bags.

It listened.

And as the townsfolk rose to their feet, gathering tools and prayers, the window breathed out a single word, steaming on the inside glass where none could reach:

“WAIT.”

The Haunted Chip Shop

Chapter Twenty-Two — The Sealing