A Tale of Teacups and Timestreams

Mr Puddleforth and the Marmalade Cat

A Tale of Teacups and Timestreams

Chapter One: The Clock That Forgot the Time

Mr Puddleforth and the Marmalade Cat Song #1

In a little stone cottage on the edge of a mossy wood, where the road turned to cobble and the wind hummed lullabies to the grass, lived Mr Archibald Puddleforth. He was retired, round, and mildly mysterious, in the way only those who own a house full of ticking clocks, peculiar books, and an unusually perceptive cat can be.

The cat in question was not your average feline. She was the colour of late-afternoon marmalade, with amber eyes like stained glass and a habit of appearing wherever you didn’t expect her—and just as often, wherever you did.

Her name, though rarely spoken, was Whiskerine.

Each morning, precisely one minute after sunrise, Whiskerine would pad into Mr Puddleforth’s bedroom and gently tap his forehead with a velvet paw. Not a claw in sight, just a subtle but firm reminder that the world was awake, and so should he be.

On this particular Sunday morning—a morning so gentle it might as well have been made of warm milk and feather-down—Mr Puddleforth awoke with a sigh, stretched, and blinked at the ceiling.

“Whiskerine,” he said sleepily, “do you suppose it will rain?”

The cat, curled elegantly at the foot of the bed, yawned.

Outside the window, the sky was buttercream and soft blue. Not a cloud in sight. But Whiskerine knew better than to trust appearances. She leapt from the bed, tail high, and padded downstairs with the graceful air of someone about to investigate a mystery.

Mr Puddleforth followed, dressing in his usual outfit of brown corduroys, a pale green shirt with elbow patches, and a mustard cardigan with far too many pockets.

In the parlour stood a great brass clock—tall, regal, and at least two centuries too old to still be ticking. But ticking it was, though not as it should. It was currently striking thirteen.

“Ah,” said Mr Puddleforth, scratching his chin. “That’s new.”

Whiskerine hopped onto the windowsill and narrowed her eyes. The garden outside looked normal—perhaps too normal.

A glimmer in the hedge. A flicker in the air. A tingle of static on the doorknob.

The world, it seemed, was about to wobble.

Chapter Two: The Hedge That Wasn’t There Yesterday

By the time Mr Puddleforth had made his tea—Earl Grey with precisely one-and-a-half teaspoons of honey—the brass clock had struck thirteen again. This time, it let out a wheeze and a creak as though it had swallowed a yawn.

“I don’t recall teaching you how to be a drama queen,” he muttered to the clock. The clock, being a rather dignified sort, did not reply. It merely blinked its pendulum once and continued ticking, now in slow, thoughtful beats.

Whiskerine had taken up her position in the garden.

She sat, statue-still, beside the raspberry bushes, staring at the hedge that separated Mr Puddleforth’s garden from the fields beyond. Only—this wasn’t the same hedge.

Where the old one had been a rather scruffy collection of hawthorn and ivy, this one was a neat wall of perfectly trimmed yew, glistening slightly in the sunlight as if someone had polished each individual leaf with lemon oil.

And nestled right in the middle of the hedge was a door.

A green door, with a round brass handle, no visible hinges, and a painted sign in curling golden script:

“Only Those with Marmalade May Pass.”

Mr Puddleforth shuffled outside, teacup in hand, and peered at the door through his spectacles.

“Well,” he said, “that’s oddly specific.”

Whiskerine turned to him with a slow blink that plainly said: Get the marmalade, old man.

Back inside, the breakfast table was already set, because Sundays in the Puddleforth household were marvels of routine. Toast waited patiently on a plate. A jar of homemade marmalade—sticky, golden-orange, and speckled with peel—sat beside it.

He spread a generous dollop on one half-slice, took a bite, and then tore off a small piece for Whiskerine, who delicately licked it off his fingers.

Then, balancing the remainder of the slice in his hand like a peace offering, he returned to the hedge-door.

Nothing happened.

He stepped closer. Still nothing.

He reached out, knocked once with the marmalade-smeared toast—and the door shivered.

Not creaked. Not opened. Shivered.

Like a cat shaking off water, or a dream trying to make itself real.

Then, with a soft pop, it swung open.

On the other side was not the field.

It was a corridor.

A long, arched corridor that sparkled faintly with floating motes of golden dust. The air inside smelled faintly of oranges, library books, and the inside of a music box. Somewhere far off, a cello played itself.

Mr Puddleforth did what any sensible man would do.

He put on his tweed cap, picked up the marmalade toast, and stepped through.

Whiskerine followed with a flick of her tail—then turned at the threshold and batted the door shut with one dainty paw.

And just like that, the garden was gone.

Chapter Three: Tea with the Custodian of Lost Hours

The corridor through the green door was neither long nor short. It bent like a question mark and hummed faintly with possibility. Mr Puddleforth, ever the gentleman, paused every few steps to sip from his tea, which, curiously, remained hot despite the obvious passage of time—or perhaps because of it.

Whiskerine padded ahead, her tail high, her marmalade fur catching flecks of glowing dust. Her ears twitched as if she were listening to invisible whispers along the walls.

The corridor ended, quite suddenly, at a brass turnstile. Beyond it, a large circular room opened up like the inside of a great clock—gears as wide as wagon wheels turned overhead, and pendulums swung in lazy arcs that defied logic. The air smelled of tea leaves, old wood, and the sort of parchment used only in ancient libraries and well-behaved dreams.

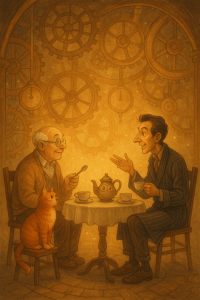

At the center of the room stood a table set for two. There were teacups, mismatched and delicate. A teapot shaped like an owl blinked sleepily. And seated across the table, reading a book upside down, was a man in a pinstriped dressing gown and spats.

“Ah,” he said without looking up, “you must be Archibald Puddleforth. And that must be Whiskerine. Please, do sit. I’ve steeped the time just right.”

Mr Puddleforth hesitated. “I believe you mean ‘tea.’”

The man looked up. His face was ageless, like a well-used coin, and his eyes sparkled with nonsense.

“No,” he said cheerfully. “I definitely mean time. I’m the Custodian of Lost Hours, and this is the Temporal Tea Room. You’ve been invited for very specific reasons, some of which I myself no longer recall, as they haven’t happened yet.”

Whiskerine leapt onto the empty chair with dignity and began delicately cleaning her whiskers.

“I’m not sure what this is all about,” said Mr Puddleforth, lowering himself into the seat. “But I was promised marmalade. Well, implied.”

“Ah yes,” said the Custodian, flipping his book the right way up. “The marmalade clause. A clever loophole. You’ve stumbled into the corridor between now and never.”

He poured tea that shimmered like starlight into the cups.

“This place,” the Custodian said, gesturing vaguely, “is where lost hours go. Forgotten minutes. Misplaced afternoons. Even those Wednesday mornings you swear never existed.”

“But why?” asked Mr Puddleforth.

The Custodian leaned in. “Because time leaks. Especially in sleepy villages. You know how sometimes you can’t remember what you were doing, or an hour passes in the blink of an eye? That’s because a mouse in a waistcoat stuffed it in his pocket and ran off with it.”

“You’re not serious.”

“I’m entirely serious. Just never solemn.”

Whiskerine meowed, low and firm.

The Custodian nodded solemnly at her. “Yes, yes, I was getting to that. The leak.”

Mr Puddleforth blinked. “Leak?”

“Time,” said the Custodian gravely, “is dripping. And something—or someone—is stealing it faster than we can catch it in teaspoons. Your clocks are confused. Your marmalade opened a door it wasn’t meant to. And if we don’t do something soon…”

He paused and took a sip.

“…there won’t be any Sundays left. Just Monday. Forever.”

Mr Puddleforth turned pale. “Eternal Mondays? You monster.”

“I’m not the monster. I’m the janitor,” said the Custodian brightly. “But you—you may just be the man for the job. You and your time-sensitive feline companion.”

Whiskerine looked proud.

Mr Puddleforth set down his teacup. “What must I do?”

The Custodian clapped his hands. “Excellent. I was hoping you’d ask. You’ll need this.”

He handed Mr Puddleforth a spoon. Not a sword, not a map, not a wand. A spoon.

It shimmered faintly with the glow of second chances and was engraved with the words:

“Stir Wisely.”

Then the gears above them groaned, and the floor began to tilt.

“Off you go!” said the Custodian cheerfully. “You’ve an appointment with the Hour Eater, and time, I’m afraid, is flying.”

With that, the chairs tipped backward, the table folded into itself, and Mr Puddleforth and Whiskerine slid down a spiral of starlit mist, gripping their teacups tightly and holding onto their breath.

Chapter Four: The Land That Forgot to Finish

Mr Puddleforth had slid down many things in his life—a bannister as a boy, a mudhill at a village fête, even a particularly embarrassing slip on an ice patch outside Mrs Figg’s Post Office—but he had never slid through time itself before.

The starlit spiral curved and twisted, and Mr Puddleforth’s teacup stayed politely intact the entire way. Whiskerine, poised as ever, rode a swirl of mist like it was a chaise lounge, her tail unfurling like a slow-motion flag.

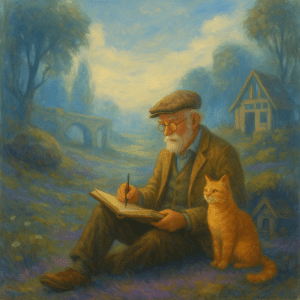

They landed gently, not with a thump or a crash, but with a gentle fwump onto a carpet of violet moss. Mr Puddleforth blinked, adjusted his spectacles, and stared.

They were in a valley.

But not just any valley.

This was a place half-dreamed and only partially stitched together. The trees were tall but didn’t quite reach their tops, ending in floating sketches. Hills faded into penciled outlines. The sky had no sun or moon—just a silvery pause, as if someone had forgotten to press play again.

“Good heavens,” whispered Mr Puddleforth. “Where are we?”

Whiskerine sniffed the moss. It smelled of lavender, cinnamon, and faint regret.

A nearby boulder shuddered, sneezed, and opened one sleepy eye. “You’re in the Unfinished Realm,” it said groggily, “where everything begins but nothing ends. Mind the puddles—they’re metaphorical.”

Mr Puddleforth removed his cap respectfully. “Charmed. And you are?”

“Boulder,” said the boulder. “And no, I wasn’t always one.”

Whiskerine pawed a flower that flickered like static, briefly turned into a teacup, and then became a flower again.

“We’re not supposed to be here,” Mr Puddleforth murmured. “Are we?”

“No one is,” said the boulder. “It’s a realm for ideas that never made it. Abandoned daydreams. Stories that forgot their own endings. Time doesn’t quite fit here. It bunches up like socks at the back of a drawer.”

Mr Puddleforth looked around. The air shimmered oddly, like it had too many thoughts and not enough vocabulary.

“How do we get out?” he asked.

“You’ll need to finish something,” said the boulder. “Something that was never finished. A tale, a tune, a tea party. Doesn’t matter what. Completion’s the only way through.”

Mr Puddleforth looked to Whiskerine, who nodded once, then took off into the distance like a stripy orange arrow.

They wandered for what felt like hours, though the sky never changed. They passed:

- A bridge that only existed halfway across a dry river

- A treehouse with no ladder and no house, just a sign that read “Tree Coming Soon”

- A poem scrawled on the wind, ending abruptly at “and then the stars—”

And eventually, a tiny cottage. Incomplete, of course. Three walls, half a roof, and a kitchen table set for two, though only one chair was real.

But sitting on the table, next to a half-written recipe for lemon drops, was a notebook.

Mr Puddleforth turned the cover. It was a diary. The last entry read:

“3rd May — I’ve nearly perfected the jam that sings. Must remember to adjust the notes. Whiskerine likes the F-sharp. Tomorrow, I’ll—”

And then, nothing.

Mr Puddleforth sat down, smoothed the page, and pulled out his handkerchief.

He dipped his spoon (the one from the Custodian, remember?) in the air and stirred slowly. As he stirred, a low hum began to fill the valley. The moss beneath his feet glowed faintly. The trees stretched, yawned, and quietly finished growing.

And then Mr Puddleforth began to write.

“—Tomorrow, I’ll hum the tune backwards and see if it gives the jam ideas. If not, I’ll add nutmeg.”

The moment his pen scratched that final g, a rush of wind circled the valley.

The unfinished world gave a sigh of relief.

The bridge built itself. The treehouse sprouted a ladder. The stars, finally, finished their sentence.

Whiskerine landed beside him, a victorious mouse-shaped thought in her jaws.

The notebook closed itself. The sky opened into blue.

A voice whispered from the wind: “Thank you.”

Then, quite suddenly, the ground dropped away—and the two were pulled upward by a ribbon of golden light, spiraling once more into the timestream.

Chapter Five: The Hour Eater’s Tea Party

Mr Puddleforth awoke on a moving train.

Or rather, what felt like a train. The seats were plush velvet, the walls carved from what might have been mahogany dreams, and the windows showed not countryside or tunnel, but vast swirling clouds of golden mist through which clock faces occasionally floated like jellyfish.

Whiskerine sat calmly on the opposite seat, her paws tucked under her, eyes half-closed in that way cats use when they want to appear relaxed but are secretly judging you.

“Well,” said Mr Puddleforth, brushing biscuit crumbs from his lap though he didn’t recall eating any. “This is… punctual.”

A voice crackled from nowhere, like an old radio tuning in mid-melody:

“Now arriving: Last Hour Before Tea. Please mind the gap in logic when disembarking.”

The train sighed to a halt. The doors opened with a squeal of violins.

They stepped out onto a platform made entirely of ticking clocks. Beneath their feet, time itself ticked, tocked, skipped, rewound, then ticked again in embarrassment.

At the end of the platform stood a sign:

“Welcome to the Unwound Court.”

Please reset your expectations.

They passed through a narrow archway and entered a wide chamber carved from swirling quartz. In the center stood a table, long as memory and cluttered with mismatched cups, half-eaten cakes, teapots that poured themselves, and forks that occasionally sighed.

Seated at the head of the table was a creature made of many things.

It wore a grandfather clock as a chest, hourglasses for eyes, and a voice like a ticking metronome.

It was the Hour Eater.

And it was waiting for them.

“Sit,” it said, not unkindly.

They did.

“Eat,” it said.

Mr Puddleforth eyed a scone that kept rewriting itself.

“Erm… thank you, but I’m full of metaphor.”

“You’ve been tampering,” said the Hour Eater. “Patching time. Closing loops. Finishing thoughts. Do you know what that does to someone like me?”

“I imagine it makes indigestion,” Mr Puddleforth offered.

“Worse. It causes rhythm. Predictability. Schedules. Order.”

It shuddered at the word.

“I feed on lost time,” the creature intoned, steam wafting from its ears like hot breath. “On distractions, delays, forgotten hours. And you—you—have been cleaning up the crumbs.”

Whiskerine arched her back. Her tail was fluffed like a bottlebrush dipped in indignation.

“I was invited,” Mr Puddleforth said calmly. “By the Custodian.”

“The Custodian is a librarian with illusions of grandeur,” the Hour Eater sneered. “He wants time neat and catalogued. I prefer it wild and overgrown. Missed appointments, long naps, wandering thoughts. That’s where the flavor is.”

Mr Puddleforth folded his arms. “Then we’re at odds.”

The Hour Eater leaned forward. “Would you like to make a wager?”

“I’m listening.”

“Simple. One cup of tea. One question. If you answer it correctly, I will return the hours I’ve hoarded. The Tuesday afternoons lost to yawns. The ten-minute intervals between two good thoughts. The childhood days you remember only in smells.”

“And if I lose?”

“You become a minute hand on my chest. Always moving, never arriving.”

Whiskerine hissed.

Mr Puddleforth took the teacup offered to him. It shimmered oddly, as though made of seconds.

“What’s the question?” he asked.

The Hour Eater leaned close. “What is the most valuable moment in time?”

Mr Puddleforth stared into his tea.

The scent of marmalade and thunderclouds rose from it.

And then he smiled.

“This one,” he said, raising the cup.

“The moment you asked me.”

Silence.

Then, like a gear slipping perfectly into place, the Hour Eater sighed.

“You’re irritatingly correct,” it said.

Around them, time rushed back into the walls. Forgotten memories rethreaded themselves. The table folded in on itself. The teapots vanished.

The Hour Eater stood.

“I’ll see you again, Archibald. Time always loops back.”

And with that, it faded—like a pause returning to music.

The train reappeared behind them, ready to carry them onward.

Mr Puddleforth turned to Whiskerine. “That could have gone worse.”

She leapt into his arms and purred a sound that meant: It still might.

They boarded the train once more, bound now for the Clockwork Grove, where the very trees kept time—and something darker had begun to whisper beneath their roots.

Chapter Six: The Clockwork Grove

The train emerged from the mist as quietly as it had entered, pulling into a station that looked as though it had grown from the forest itself. Ivy curled over the wooden beams. Golden leaves drifted from overhead. And in the distance, soft clicks and chimes echoed through the trees.

Mr Puddleforth stepped down onto the platform, Whiskerine beside him. The moment his shoes touched the ground, he felt it—a gentle thrum beneath his soles, like the earth itself was ticking.

“Welcome to the Clockwork Grove,” said a voice overhead.

A small bird with silver feathers and a cogwheel for an eye landed on a post. “The trees here keep time. Literally. They track seasons, measure centuries, and sometimes get tangled in themselves.”

The forest beyond the station shimmered. Trees grew in orderly lines, their trunks shaped like twisted spirals of brass and bark. Their leaves were paper-thin and spun slowly in the breeze, each one marked with faint runes that glowed in the shade.

“It’s beautiful,” whispered Mr Puddleforth.

“It’s dangerous,” said the bird. “If a tree doesn’t like your timeline, it might try to rewrite it.”

Whiskerine flicked her tail defiantly and strode forward.

They followed a winding path lined with pebbles shaped like sundials and mushrooms that rang like tiny bells when stepped on. Deeper into the grove, the ticking grew louder—not mechanical, but organic, like trees breathing seconds.

They passed a tree that grew backwards—its roots in the air and its crown buried in the soil. Another had grown so old it had looped its trunk into a perfect ring, forever marking a moment that had once been—and might be again.

At the heart of the grove stood a tree unlike any other.

It was vast, with silver bark that pulsed like a heartbeat and branches that moved of their own accord, rearranging themselves in slow patterns. From each limb hung a glowing pocket watch, gently swinging.

This was the Heart Tree.

And it was dying.

Several watches had stopped.

Others blinked in and out of sight, glitching like a bad memory.

At its base stood a woman in a long black coat, winding one of the stopped watches with a crooked key. Her hair was streaked with copper wire. Her eyes were pale blue, like frost trapped in crystal.

“I was wondering when you’d arrive,” she said without looking up. “You’ve left crumbs all over the timeline, Mr Puddleforth.”

“Sorry,” he said automatically, though he wasn’t quite sure what for.

She stood and turned.

“I am Tessitura, the Grove Keeper. And this,” she gestured to the faltering tree, “is the central loop. It keeps the balance between yesterday and tomorrow. It knows what ought to happen, and when.”

Whiskerine meowed.

Tessitura nodded. “Yes, the Hour Eater has gnawed at its roots.”

Mr Puddleforth stepped forward. “Can it be healed?”

Tessitura held out the crooked key. “Only by someone who still believes in moments. Someone who treasures the now—not just the past, not just the future.”

Mr Puddleforth took the key.

And suddenly—memories:

- A quiet afternoon with tea and toast and a book he’d read a dozen times.

- His first marmalade sandwich, which he’d dropped, then eaten anyway.

- The laughter of someone long gone, echoing faintly but warmly.

- The exact weight of Whiskerine on his lap on rainy evenings.

He stepped toward the Heart Tree.

Each pocket watch he passed began to glow. The ticking grew steadier. The breeze slowed.

He reached a cracked, stopped watch that dangled lower than the rest. Gently, he placed the crooked key inside and turned.

The watch blinked.

Ticked.

And began again.

One by one, the others followed.

The tree pulsed. Its branches shook. Its leaves flared like tiny suns.

And then, silence.

But not empty silence.

Peaceful silence.

Tessitura smiled. “You’ve reminded the tree why time matters.”

Mr Puddleforth looked up at the swirling canopy. “Because we fill it. With stories. With tea. With small, perfect things.”

Whiskerine purred.

Tessitura bowed her head. “The Custodian was right. You’re the perfect wanderer.”

A path opened through the grove—straight, golden, and leading to a tower that shimmered on the horizon.

“Your journey isn’t over,” she said. “One final loop. The beginning of endings.”

And with that, Mr Puddleforth and Whiskerine walked onward, beneath trees that now ticked softly, kindly, full of purpose once more.

Chapter Seven: The Tower at the End of the Tick

The golden path led Mr Puddleforth and Whiskerine through the last of the Clockwork Grove, beyond whispering trees and blinking watches, until the leaves gave way to open sky.

There, at the top of a hill that looked as though it had been carved from folded parchment, stood The Final Tower.

It wasn’t tall—not in the way castles or lighthouses are. It was deep, burrowing downward into the very fabric of time. From the outside, it looked simple: round, smooth, the colour of forgotten fog. At its peak ticked a single, slow-turning weathercock, its beak forever pointing toward Moments Yet To Come.

“This is where it ends,” murmured Mr Puddleforth.

Whiskerine didn’t reply. She sat and washed her paw calmly, but her tail flicked in tight, nervous curls.

The door was unlocked.

Inside, a spiral staircase wound down, not up, its steps inscribed with stories—tiny carvings, etched into stone, of lives lived fully: laughter, sorrow, marmalade toast. As they descended, the ticking grew louder. Time itself beat like a slow drum through the walls.

At the base of the tower, they entered a chamber unlike any they’d seen before.

A circular room. Empty, save for a mirror.

But it was no ordinary mirror.

It rippled.

Inside it, they saw scenes from their own lives—memories re-spooling like ribbons.

Mr Puddleforth saw himself as a boy, chasing butterflies through meadows. He saw rainy Tuesdays with forgotten friends, old birthdays, quiet moments of sadness that had since been buried beneath bus timetables and old shoes.

And Whiskerine—he saw her, too. But not always as a cat.

There were flickers—of a fox, a hare, a flame. Of something older than memory. She had always been there, in one form or another, guarding him quietly, faithfully.

“Ah,” came a voice behind them. “You’ve reached the Core of When.”

The Custodian had returned, now wearing a crown of cracked teacups and a robe made entirely of stitched-together calendars.

“This is the centre,” he said, “where every second that ever was folds in on itself like the corner of a napkin. You’ve done well, Puddleforth. The tree is mended. The Eater appeased. The leak sealed. But before you go back, you must do one final thing.”

Mr Puddleforth turned to face him. “Name it.”

The Custodian held out a small object. A clock key—just like the one from the Grove, but this one was tarnished, ancient.

“You must wind your own life,” the Custodian said gently. “No one else can.”

Mr Puddleforth held the key in both hands. “And what if I overwind it?”

The Custodian smiled. “Then you’ll live twice as much.”

A pause. A heartbeat. A purr.

And Mr Puddleforth turned to the mirror.

He saw his own reflection—older, yes, but kind. A face lined not with sorrow, but with stories. He lifted the key and turned it in the air, just once.

Click.

The mirror stopped rippling.

And instead of showing his past, it showed his future—but only in flashes:

- A picnic in springtime.

- A letter from an old friend.

- Whiskerine curled up on his lap beside a roaring fire.

- A new book, half-written.

He smiled. “That’ll do.”

With that, the mirror vanished. The chamber dissolved into golden mist.

And the next thing he knew—

He was back.

Home.

In his armchair.

The brass clock on the wall ticked quietly, correctly.

Whiskerine stretched, leapt onto his lap, and curled up with a soft sigh.

Outside, the Sunday morning was just beginning again.

Epilogue: The Perfectly Ordinary Day

Monday came, as Mondays always do.

But it was not the grim, grey Monday feared by overworked shopkeepers and yawning schoolchildren. This Monday was mild. It smelled faintly of toast and looked like it had been ironed with care.

Mr Puddleforth sat on his favourite bench beneath the old apple tree in his garden, a checked blanket over his knees and a newspaper he didn’t really intend to read flapping gently in his lap. Whiskerine lounged across the back of the bench like an orange scarf, blinking slowly at the breeze.

“Anything interesting in the paper?” asked a voice.

It was Mrs Dabble from next door, leaning over the fence with a watering can.

“Oh, only that time appears to be behaving itself again,” Mr Puddleforth replied with a smile.

Mrs Dabble chuckled. “That’s nice. I lost all of last Thursday once, but it turned up in my sock drawer.”

The garden ticked gently. The brass clock in the parlour could be heard through the open window, chiming the correct hour with cheerful pride. The tea kettle, left to its own devices in the kitchen, whistled politely.

A small parcel arrived in the afternoon. It had no label and was tied with a string made of woven light.

Inside: a teaspoon.

Engraved upon it were the words:

“Thanks for the stir. —The Custodian”

That evening, Mr Puddleforth made a second cup of tea, just in case a guest arrived unexpectedly.

He and Whiskerine watched the stars bloom, one by one, like forgetful fireflies remembering their cue.

The clocks all ticked in harmony.

And just for a moment—just a breath—the world paused.

Not because it was broken.

But because it was perfect.