Sherlock Holmes

The Case of the Emerald Alchemist

The fog clung to the cobbled streets of London like a wet shroud, a fitting curtain for the bizarre case that landed on my desk. It began on a dreary Tuesday morning, with the postman’s familiar rap echoing through the corridors of 221B Baker Street. Among the bills and circulars was an anonymous package, wrapped in coarse brown paper and addressed to my friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes. It contained no return address, no postmark of note, only a peculiar scent—a faint, metallic odor that reminded me of a blacksmith’s forge mixed with something strangely organic.

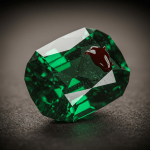

Holmes, ever the keen observer, unwrapped the parcel with a delicate precision, his long fingers moving with a surgeon’s certainty. Inside, nestled on a bed of crumpled velvet, was a single, perfect emerald. Its facets caught the faint light from the window, casting a viridescent glow upon the room. But what truly commanded our attention was the dark, glistening smear upon its surface, a stain that could only be blood.

A small, elegant note, penned in a graceful, almost archaic script, lay beside it. It simply read: “The Alchemist’s debt is paid.”

I recoiled slightly. “Good heavens, Holmes, is that… human blood?”

My friend, without a word, brought the emerald closer to his nose, a curious intensity in his gaze. He inhaled deeply, a slight frown creasing his brow. “Not human, my dear Watson. Porcine,” he declared, his voice low and confident. “A prize-winning hog, I’d wager, judging by the richness of the feed in its blood. The animal was exceptionally well-nourished.”

The emerald itself was a marvel. He examined it with his magnifying glass, his eyes tracing the invisible lines of its history. “This stone… it is of a purity seldom seen. From a forgotten mine in the Ural Mountains, a location no longer producing stones of such flawless quality. The inscription, however,” he said, holding it up to the light, “is the most perplexing part.” He pointed to a barely visible, microscopic etching on one of the facets, a series of symbols that looked more like an ancient glyph than any known writing. “It points to a world of ancient secrets. And my mind, my dear Watson,” he said, a glint of excitement in his eyes, “is instantly alight.”

Our investigation led us down a winding path, from the opulent parlors of a disgraced Lord to the grimy underbelly of London’s dockyards. The Lord, a certain Bartholomew Finch, had squandered his fortune on occult antiquities, convinced he could unlock the secrets of immortality. He had recently been visited by a man he described only as “The Alchemist,” a shadowy figure who spoke in riddles and offered him a chance to reclaim his lost wealth. Finch had purchased a small, oddly-shaped key from him, a transaction that had cost him his last sovereign. The key, he said, was for a “great lock” that The Alchemist was soon to open.

Next, we found ourselves in the dark and dingy workshop of a peculiar chemist named Silas Crum. Rumors abounded that he was experimenting with forbidden formulas, dabbling in a forgotten branch of science that bordered on the magical. Crum, a nervous and twitchy man, confessed to having been commissioned to create a special chemical solution, a solvent for a substance he was not told the nature of. “He paid me in… emeralds,” Crum stammered, his eyes darting to a small pouch on his shelf. “Flawless, sir. Perfectly flawless.”

The emerald, it became clear, was a key, a clue in a dangerous game. It was a test, a challenge from a master criminal who believed they had finally created a puzzle too intricate for even Holmes to solve. This “Alchemist” was not after wealth or power in the traditional sense. His motive was far more sinister: he was a collector of secrets. He stole not objects, but knowledge—ancient recipes, lost languages, and forbidden sciences. The emerald was a down payment for his grandest theft yet, a legendary codex said to hold the secret to transmuting base metals into gold, a text believed to be a myth for centuries. He believed that with this knowledge, he could unravel the very fabric of reality and become a god among men.

Through a painstaking process of deduction, cross-referencing ancient texts and chemical compound charts, Holmes finally cracked the microscopic code on the emerald. It was not a language, but a chemical formula, one that had been lost to science for centuries. It was the formula for a potent and highly volatile explosive. The blood on the stone, the porcine blood, was a mockery of a ritual, a red herring meant to throw us off the scent. The emerald was not a gift, but a component.

Our pursuit led us to an abandoned, gas-lit foundry in the East End. The air was thick with the smell of rust and coal. Inside, standing over a bubbling cauldron, was The Alchemist himself, a gaunt, skeletal figure with a crazed look in his eyes. In one hand, he clutched the codex he had stolen, and in the other, a small bronze mortar and pestle.

“Sherlock Holmes,” he hissed, his voice a dry whisper. “You are too late. The final transmutation is at hand. Soon, I will hold the power of the gods!”

Holmes, with his characteristic flair, stepped forward, his silhouette framed against the flickering gaslight. “You are not an alchemist, sir. You are a coward,” he said, his voice calm and steady. “You are not creating gold. You are creating a weapon. The cauldron isn’t a vessel for creation, but a bomb waiting to detonate.”

The Alchemist’s eyes widened in horror and then narrowed in a fit of manic rage. “You know nothing!” he shrieked, raising the mortar and pestle.

But it was then that Holmes revealed the final piece of the puzzle. The tiny, elegant note, “The Alchemist’s debt is paid,” was not a statement of completion, but a subtle threat. It was a signal to his accomplice, a chemist whom he had paid with the emeralds. The note was a final instruction, a key to triggering the volatile explosive he had just described.

Just as The Alchemist moved to drop the contents of his mortar and pestle into the cauldron, Inspector Lestrade and his men, alerted by a telegram from Holmes, burst in through the back. The Alchemist, defeated, watched his life’s work—the codex and his grand, destructive plan—vanish into the night air as the police cuffed him.

In the end, it was not a chase or a brawl that brought the case to its close, but a battle of wits. The fog outside had begun to dissipate, and a faint sliver of moonlight broke through the clouds. As we left the foundry, Holmes, standing amidst the grime and steam, simply adjusted his deerstalker, a small, satisfied smile on his lips. “The human mind, my dear Watson,” he said, turning to me, his eyes alight with a deep and abiding curiosity, “is the most fascinating puzzle of all.”