Still on the Timetable

Chapter One

The Morning Express

At precisely six minutes past six each morning, the line began to breathe.

It was not something most people noticed.

The modern railway had become a quiet thing over the years — electric trains gliding in and out of stations with the faintest whisper, signals changing colour without sound, doors opening with polite electronic certainty.

But the old line still remembered how to breathe.

First came the distant rhythm, too slow to be mistaken for anything else.

A soft, measured beat carried across the fields.

Then a thread of smoke appeared above the hedgerows.

Then steam.

And then, exactly as the timetable promised, the Morning Express arrived.

The platform at Hawthorn Junction was never busy at that hour.

Two commuters stood beneath the lamp at the far end, as they always did.

One checked a watch.

The other did not.

They both looked up when the sound reached them.

Not because they were surprised — but because listening was part of the journey.

The signal ahead showed green.

It had shown green every morning for as long as either of them could remember.

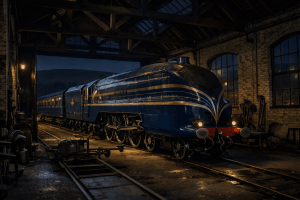

The locomotive came into view around the gentle curve in the track.

Blue in the morning light.

Streamlined.

Certain.

Steam drifted along the casing like breath on cold air.

The exhaust beat settled into its familiar rhythm — steady and unhurried — as the engine rolled toward the platform.

The driver eased the regulator closed with practised calm.

The locomotive slowed without complaint.

It always did.

No one on the platform took photographs.

No one pointed.

The Morning Express was not unusual.

It was simply on time.

The buffers stopped precisely where they always stopped.

The carriages aligned perfectly with the platform markings.

A door opened.

Someone stepped down.

Someone stepped aboard.

The guard raised a hand.

The driver answered with a short, gentle whistle — not loud, not ceremonial, just enough.

Steam lifted briefly from the cylinders.

The locomotive began to move again.

The commuters did not watch it leave.

They never did.

The important part was the arrival.

As the train pulled away, the station returned to stillness.

The signal remained green.

The rails hummed for a moment longer, then fell silent.

Across the fields, the smoke thinned and disappeared into the morning sky.

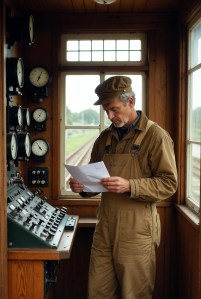

Inside the small signal box at the end of the platform, Mr Calder closed the timetable.

He did this every morning after the train passed.

He had done it for forty-two years.

Before him, his father had done the same.

Before that, someone else whose name no one remembered.

Mr Calder looked once more at the entry on the page.

He did not need to read it.

He never did.

Still, he always checked.

06:10 — Mainline Express — Steam

He nodded to himself, satisfied, and reached for the kettle.

Because the railway, like the timetable, was exactly as it had been the day before.

And would be again tomorrow.

Chapter Two

The Workshop That Never Closed

The workshop stood behind the old goods yard, where the railway curved away from the town and the modern station could no longer be seen.

It was built of dark brick, with tall windows clouded by years of steam and weather. The roof beams inside were blackened with smoke from another age, though no one now working there remembered the day the smoke first settled.

The sign above the wide wooden doors read simply:

LOCOMOTIVE WORKS

The letters had been repainted many times, but never changed.

Inside, the air was warm even in winter.

It smelled of oil, metal, coal dust, and hot water — the smell of work that required patience.

A boiler stood at the far end of the workshop, quiet but still holding yesterday’s warmth. Beside it lay tools arranged with careful order: spanners worn smooth by hands long gone, hammers polished by decades of use, measuring gauges kept in wooden boxes lined with felt.

Nothing in the workshop was new.

Nothing needed to be.

Mr Hargreaves arrived first, as he always did.

He hung his coat on the same hook he had used for twenty-seven years and set a kettle on the small iron stove near the workbench.

The kettle was older than he was.

He checked the water level in the boiler without hurry.

Steam engines did not respond well to hurry.

A few minutes later, the large doors opened with a familiar creak, and Ellie stepped inside, brushing the cold from her hands.

She was the youngest engineer in the workshop, and the only one who had never known a railway without electric trains.

“Morning,” she said.

“Morning,” Mr Hargreaves replied, without looking up.

Ellie walked to the long workbench where a set of valve components lay arranged on cloth.

She picked one up carefully.

“Still warm,” she said.

“They always are,” Mr Hargreaves answered. “She doesn’t like cooling down too much overnight.”

Ellie nodded, as if this were perfectly ordinary.

In the workshop, it was.

Along the back wall stood shelves filled with parts that no longer existed anywhere else.

Injector fittings.

Copper pipe lengths.

Hand-cut gaskets.

Boxes of rivets.

Patterns for castings.

Each shelf had a label written in neat black paint.

The handwriting belonged to three different generations of engineers.

Ellie had begun adding labels of her own.

At half past six, the sound arrived through the open roof vents.

Soft at first.

Then unmistakable.

The slow, even exhaust beat of a steam locomotive settling into motion.

Mr Hargreaves paused with a spanner in his hand.

Ellie stopped polishing the valve casing.

They did not speak.

They listened.

The sound passed across the fields behind the workshop and faded toward the main line.

“She’s running well today,” Ellie said.

“She always does,” Mr Hargreaves replied.

He did not say it with pride.

He said it the way someone might comment on the weather.

On the far wall hung a framed photograph of the workshop taken long ago.

The image showed:

- a row of steam locomotives

- men in heavy coats

- a crane lifting a boiler

- smoke drifting through the roof beams

The workshop had once been crowded.

Now there were only three engineers left who understood the work completely.

Mr Hargreaves.

Mr Singh, who would arrive later.

And, one day, Ellie.

The kettle began to whistle.

Mr Hargreaves poured two cups of tea.

Outside, the morning express continued along the line, unseen but certain.

Inside, the workshop returned to its quiet rhythm:

metal on metal,

water warming,

tools being lifted and set down again.

The kind of rhythm that does not appear in timetables,

but keeps them true.

On a small clipboard near the door hung a maintenance sheet.

The top line read:

6234 — Princess Continuance

Below it, in careful handwriting:

Service: Daily

Ellie finished polishing the valve casing and placed it back on the cloth.

“Do you think she’ll ever stop running?” she asked.

Mr Hargreaves considered this for a moment.

Then he shook his head.

“No,” he said.

“I think the railway would stop first.”

Chapter Three

The Footplate

The crew signed on before sunrise.

They always did.

The small depot office beside the shed smelled faintly of coal smoke and paper, the way railway buildings often did when they had been standing for a long time.

Tom Barrett signed the logbook first.

He had been driving steam locomotives for longer than most railways still owned them.

Below his name, in steadier, newer handwriting, Liam Doyle signed beside the word Fireman.

The pen scratched softly across the page.

That sound, too, was part of the morning routine.

Outside, the locomotive waited.

Even at rest, Princess Continuance looked prepared for movement.

A faint warmth drifted from the casing.

A thin line of steam escaped from a valve near the cylinders.

The metal of the driving wheels held the memory of yesterday’s run.

The engine had never quite learned how to be cold.

Liam climbed onto the footplate first.

He checked the water level in the gauge glass, then the pressure needle.

Both were exactly where they should be.

“They’ve left her right,” he said.

“They always do,” Tom replied, climbing up behind him.

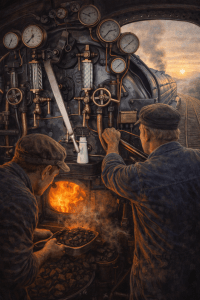

The cab of a steam locomotive was not large.

Two men, a shovel, a firebox door, and the steady breathing of the boiler filled the space.

The smell was familiar:

coal,

hot oil,

iron,

and steam.

Liam opened the firebox door.

Orange light spilled into the cab.

The fire was already alive.

He lifted the shovel and added coal with practised movements, spreading it evenly across the glowing bed.

Steam locomotives did not like sudden changes.

They preferred patience.

Tom watched the pressure gauge.

The needle rose slowly, as expected.

“She remembers the road,” Tom said quietly.

Liam nodded.

He believed that, though he would never say so outside the cab.

At five minutes to departure, Tom opened the cylinder drain cocks.

Steam hissed downward toward the rails.

The sound echoed gently inside the shed.

Then Tom placed one hand on the regulator.

Not pulling.

Not pushing.

Just resting there.

Waiting.

The guard’s whistle sounded from the platform.

Tom answered with the locomotive’s own whistle — short, polite, and certain.

He eased the regulator open.

The locomotive responded immediately.

Not eagerly.

Not reluctantly.

Just correctly.

The driving wheels began to turn.

Once.

Twice.

Then steadily.

Princess Continuance rolled forward into the morning.

From the cab, the world looked different.

Signals mattered more.

Gradients mattered more.

Time mattered more.

Everything else could wait.

The exhaust beat settled into its familiar rhythm as the locomotive cleared the points and reached the open line.

Tom adjusted the regulator slightly.

Liam added another small shovel of coal.

Neither spoke.

They did not need to.

The locomotive filled the silence.

Sunrise spread across the fields as they gathered speed.

The casing of the engine caught the light.

Steam drifted back along the carriages.

The rails ahead shone silver.

Tom glanced at the pressure gauge once more.

Perfect.

“She likes mornings,” Liam said.

Tom nodded.

“Yes,” he said.

“She always has.”

The Morning Express continued along the mainline, exactly as the timetable required.

Behind them, the depot shed grew smaller.

Ahead of them, the railway stretched into another ordinary day.

And in the steady rhythm of the exhaust beat, the locomotive spoke the same quiet promise it had spoken for years:

Still running.

Still working.

Still on the timetable.

Alright — now we move into the gentle turning point of the story.

So far we have:

- Chapter One: the timetable and the morning express

- Chapter Two: the workshop

- Chapter Three: the footplate crew

Now Chapter Four introduces the first small disturbance — not mechanical, but administrative.

Chapter Four

The Letter

The letter arrived in the afternoon post.

Mr Calder noticed it immediately, because the envelope was larger than most and carried the railway crest printed neatly in the corner.

He placed it on the small desk inside the signal box and finished writing the time of the passing freight train in the logbook before opening it.

The railway had taught him that nothing improved by being opened too quickly.

Outside, the line lay quiet beneath a pale sky.

The morning express had passed hours earlier.

The rails no longer hummed.

The station platform was empty except for a pigeon that had grown accustomed to railway schedules.

Mr Calder slit the envelope carefully with a ruler.

Inside was a single sheet of paper.

Typed.

Official.

Timetable Revision Notice

Mainline Services Review

Mr Calder read the letter once.

Then again.

Then he set it flat on the desk and removed his glasses.

The notice explained, in polite and efficient language, that the railway was reviewing several long-standing services in order to improve scheduling consistency.

One entry had been highlighted in pencil.

Not by Mr Calder.

By someone else, somewhere further along the line of responsibility.

06:10 — Mainline Express — Steam

Mr Calder did not feel alarmed.

Railways produced letters the way locomotives produced steam.

Most of them drifted away without consequence.

Still, he folded the paper neatly and placed it beside the timetable.

He poured himself tea.

The kettle, as always, took its time.

Later that afternoon, he walked down the platform toward the station office.

Mrs Ellison, who sold tickets whether anyone needed them or not, looked up as he entered.

“You’ve got that look,” she said.

“What look?” Mr Calder asked.

“The timetable look.”

He handed her the letter.

She read it slowly.

“Review,” she said.

“Yes.”

“That usually means someone thinks something has been happening for too long.”

“Yes.”

Mrs Ellison placed the letter on the counter.

“Well,” she said, “the Morning Express has been happening for quite a long time.”

They did not speak for a moment.

The station clock ticked loudly on the wall.

“Do you remember when it started?” Mrs Ellison asked.

Mr Calder thought.

“No,” he said.

“My father didn’t either.”

“That sounds about right,” she said.

Outside, the signal changed from red to green for no particular reason except that the line ahead was clear.

It remained green for a while.

Then returned to red again.

The railway continued its small conversations with itself.

That evening, Mr Calder carried the letter home in his coat pocket.

He did not intend to show it to anyone, but he did not want to leave it behind either.

The paper felt strangely heavy.

At the workshop the next morning, Mr Hargreaves found the letter pinned to the notice board beside the maintenance sheet for 6234 Princess Continuance.

He read it once.

Then he poured tea.

Ellie read it next.

“Review,” she said.

“Yes,” Mr Hargreaves replied.

“They won’t stop it,” Ellie said.

Mr Hargreaves did not answer immediately.

Steam work taught patience.

“We’ll see,” he said.

Far away, on the open line, Princess Continuance pulled the Morning Express beneath a sky that looked exactly like yesterday’s.

The exhaust beat remained steady.

The pressure gauge remained true.

The timetable remained correct.

For now.

Alright — this is where the rhythm changes slightly.

Not dramatically.

Just enough to be noticed.

Chapter Five

The Morning That Was Late

The workshop was quiet when Mr Hargreaves arrived.

Not silent — workshops were never silent — but quieter than usual, as if the building itself were waiting for something.

He hung his coat on the familiar hook and looked toward the shed.

The locomotive stood inside, still and dark.

No warmth drifted from the casing.

No thin thread of steam escaped into the morning air.

Ellie arrived a minute later.

She stopped in the doorway.

“That’s not right,” she said.

“No,” Mr Hargreaves agreed.

The locomotive had not cooled overnight.

That was unusual.

Princess Continuance preferred to keep a little heat in the boiler, even when resting.

This morning, the metal looked dull and cold.

Mr Singh entered through the large doors, carrying a small toolbox.

He set it down without speaking.

All three of them looked at the engine.

“Nothing wrong,” Mr Singh said after a moment.

“Just not started.”

The firebox door opened with a heavy sound.

Inside, only grey ash remained.

Ellie began clearing the grate.

Mr Hargreaves checked the water level.

Mr Singh prepared the kindling.

They moved slowly, not because they were unsure, but because the moment felt unfamiliar.

Outside, the sky brightened.

The clock on the workshop wall showed half past five.

The locomotive should have been breathing by now.

At the depot office, Tom Barrett signed the logbook.

He paused before writing the time.

Liam Doyle stood beside him, listening.

The shed was too quiet.

“Something holding them up?” Liam asked.

Tom shook his head.

“No.”

They walked toward the locomotive together.

The smell of coal returned first.

Then the sound of the fire being built.

Then, finally, the small, dry cough of warming metal.

The engine was waking.

Just later than usual.

“Morning,” Tom said.

“Morning,” Mr Hargreaves replied.

No one mentioned the delay.

The pressure gauge needle began its slow climb.

Ellie added coal carefully.

Mr Singh watched the injectors.

The workshop clock moved toward six.

In the signal box at Hawthorn Junction, Mr Calder looked at the line.

The signal stood at red.

It had never needed to wait long before.

He did not touch the lever.

He simply watched.

Steam gathered beneath the casing.

Valves ticked softly.

The locomotive remembered itself.

At six minutes past six, the Morning Express was usually already moving.

Today, it was not.

But the railway did not panic.

Railways understood waiting.

Tom climbed into the cab.

Liam followed.

The fire burned properly now.

Pressure rose.

Water level steady.

Everything correct.

Just late.

At twelve minutes past six, the locomotive moved.

Not hurried.

Not apologetic.

Just ready.

Steam drifted along the platform at the depot as Princess Continuance rolled forward.

The wheels turned with their familiar certainty.

The exhaust beat settled into its calm rhythm.

In the signal box, Mr Calder moved the lever.

The signal changed from red to green.

The Morning Express passed beneath the window.

Late by six minutes.

Running perfectly.

Mr Calder opened the timetable and made a small note in the margin.

He did not write “delay.”

He wrote:

“Started later.”

The train gathered speed across the fields.

Behind it, the workshop returned to its quiet work.

Inside the shed, warmth lingered again.

Nothing had broken.

Nothing had failed.

But something had been remembered.

The locomotive did not run by habit alone.

It ran because people began it each morning.

And that mattered.

Then I’ll take the story toward its quiet resolution — but with the railway-office moment woven into it, so the ending feels earned rather than sudden.

We’ll let the railway decide, in its own careful way.

Chapter Six

Still on the Timetable

The railway office was smaller than people expected.

Visitors imagined long rooms filled with maps and telephones, but the office responsible for the mainline timetable contained only three desks, a large wall calendar, and a window overlooking a yard where nothing moved very quickly.

Mr Penrose read the report in silence.

Across the desk, Miss Alden waited.

On the paper, one entry had been circled in pencil.

06:10 — Mainline Express — Steam

“Delay recorded,” Mr Penrose said.

“Yes,” Miss Alden replied.

“Six minutes.”

“Yes.”

He nodded slowly.

“Cause?”

Miss Alden checked the sheet.

“Locomotive preparation began later than usual.”

Mr Penrose considered this.

“That happens sometimes,” he said.

“Yes,” she agreed.

Outside the window, a diesel shunter moved three wagons from one siding to another and stopped again, as if satisfied with the effort.

Mr Penrose folded the report.

“How long has that service run?” he asked.

Miss Alden did not need to look.

“Before the current timetable system,” she said.

“Before the previous one as well.”

Mr Penrose nodded.

He opened the timetable book.

The pages were thin from use.

He found the entry quickly.

06:10 — Mainline Express — Steam

He looked at it for a long moment.

Then he reached for a pencil.

Miss Alden watched carefully.

He wrote one word beside the entry.

Not “cancelled.”

Not “reviewed.”

Not “modernised.”

Continue

He closed the timetable.

“That will do,” he said.

The next morning, the workshop was warm before dawn.

Ellie arrived to find the boiler already holding gentle heat.

Mr Singh was checking the valves.

Mr Hargreaves poured tea.

The locomotive stood inside the shed, breathing quietly.

Tom Barrett signed the logbook.

Liam Doyle checked the coal.

Neither spoke about yesterday.

Railways rarely discussed small interruptions once they had passed.

At six minutes past six, the locomotive moved.

Exactly as before.

Steam lifted into the morning air.

The exhaust beat found its steady rhythm.

The wheels turned with calm certainty.

At Hawthorn Junction, the two commuters stood beneath the lamp.

One checked a watch.

The other did not.

They listened.

The signal showed green.

The train arrived on time.

The buffers stopped precisely where they always stopped.

A door opened.

Someone stepped down.

Someone stepped aboard.

The guard raised a hand.

The driver answered with a short, gentle whistle.

The Morning Express departed.

Across the fields, the sound faded into the distance.

The rails hummed briefly, then fell silent.

In the signal box, Mr Calder opened the timetable and looked at the entry once more.

He did not need to read it.

He never did.

Still, he always checked.

06:10 — Mainline Express — Steam

He nodded to himself and closed the book.

Because the railway had decided — quietly, without ceremony — that some things were not finished yet.

And Princess Continuance continued along the mainline, exactly as she always had.

Still running.

Still working.

Still on the timetable.

Author’s Note

Railways are full of things that end.

Lines close.

Engines are withdrawn.

Stations fall silent.

Timetables change.

But now and then, something continues — not because of ceremony or preservation, but because people quietly decide to keep it going.

A locomotive runs because someone lights the fire.

A workshop remains open because someone unlocks the door each morning.

A timetable stays the same because no one finds a good reason to change it.

Still on the Timetable is not really about a steam locomotive, though Princess Continuance is at its heart. It is about continuity — the small, steady care that allows the past to travel beside the present without fuss or announcement.

The railway in this story is imagined, but the feeling behind it is very real. Many things in the world endure not through grand decisions, but through ordinary people doing their work well, day after day.

And sometimes, that is enough to keep an engine running.

Gerrard T. Wilson