Chapter Three: The Hitchhiker with a Bad Memory

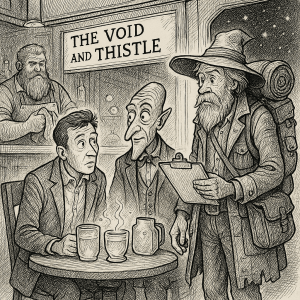

The morning after the end of the world dawned bright and cheerful in the pub at the edge of deletion, which was an achievement given that the pub technically existed in a region of space where mornings, afternoons, and evenings were theoretical concepts.

Gerry Wilson awoke in a booth with a small glass umbrella stuck to his forehead. Zorb Blenkinsop was slumped beside him, snoring gently and holding a cocktail that had fossilised during the night.

The jukebox was still humming the same tune it had been playing for six hours straight, a melancholy ballad called Love Me Tenderly, My Quantum State is Collapsing.

Gerry rubbed his eyes. “Where are we?”

Zorb blinked. “Inside a hangover. Quite a deep one, by the feel of it.”

The bearded barman grunted. “You’re lucky. Last night you were trying to rent the jukebox for interdimensional travel.”

“Did it work?” asked Gerry.

“No,” said the barman. “But you did manage to offend a galaxy. It left early.”

Zorb groaned. “Ah, yes. The Andromedans. No sense of humour.”

The barman dropped two mugs of coffee on the table. They were thick, dark, and emitted faint radio signals.

After several gulps and a few cautious blinks at the view outside the window, Gerry began to feel almost alive again. Stars drifted lazily past, blinking as if gossiping about him.

Zorb pulled out his glowing tablet. “We can’t stay here,” he said. “Flumm will have filed a report by now. The Bureau will be sniffing around for us.”

“I don’t suppose they’ll just forget we exist?”

Zorb frowned. “Forgetfulness is rare in bureaucracy. They prefer misplacing things permanently.”

As if summoned by irony, the pub door creaked open and a figure stepped inside.

It was a tall man in a tattered coat that appeared to be made of old library cards. He wore three pairs of sunglasses and a backpack shaped like a small moon. He looked around, confused, then walked straight into a chair, apologised to it, and sat down.

The barman raised an eyebrow. “Morning, Hargle.”

“Is it?” said the man. “I keep losing track.”

Zorb perked up. “Hargle Ploon! I thought you were dead.”

“I might be,” said Hargle thoughtfully. “It’s hard to say. My memory isn’t what it used to be. Or what it will be. Or whichever tense applies.”

He fished something from his coat pocket. It was a small, metallic device that whirred softly.

Gerry looked at it. “Is that a recorder?”

“Memory stabiliser,” said Hargle. “Keeps track of who I am, where I am, and whether I’ve already done this conversation before.” He pressed a button and a tiny hologram popped up, showing a younger version of himself saying, ‘Don’t trust anyone named Zorb.’

Hargle squinted at Zorb. “Do I know you?”

“Only in a strictly metaphorical sense,” said Zorb quickly.

The hologram added, ‘Especially if he owes you money.’

Zorb laughed nervously. “Ah, yes, well. Time is a flat circle. And I have no pockets.”

Gerry studied Hargle with curiosity. “You’re a hitchhiker?”

“Was, am, and possibly will be,” said Hargle. “Been travelling the galaxy since before time began, or maybe next Tuesday. Hard to recall.”

“Do you travel for work or pleasure?”

“Mostly confusion.”

He took a long sip from his drink, which immediately began to evaporate in protest.

Zorb leaned forward. “We could use someone like you. We’re fugitives.”

Hargle looked impressed. “Splendid. I love fugitives. They make such interesting mistakes.”

The barman snorted. “You’ll fit right in. None of you remember to pay your tab anyway.”

Outside the pub, the void shimmered again. A faint outline of a blue planet appeared for a fraction of a second before vanishing. Gerry caught the reflection in his glass.

“Did you see that?” he asked.

“See what?” said Zorb.

“The Earth. Or something like it.”

Zorb glanced out the window. “Probably a mirage. Space is full of them. Whole civilisations pop up and vanish before lunch.”

Hargle’s memory device beeped urgently. The hologram flickered back on.

‘If you see a planet trying to reappear after deletion,’ it said, ‘run.’

Hargle frowned. “That sounds like good advice from someone clever.”

Zorb stood. “Time to go. Now.”

They hurried out of the pub and into the Slightly Toasted Toaster Mk II.

The beard behind the bar called after them, “Don’t forget your bill!”

Zorb waved. “Put it on the Bureau’s tab!”

The ship’s door closed with a clang. As it lifted off, Gerry glanced one last time through the window.

The spot where the Earth had been was glowing again, this time brighter, pulsing like a heartbeat.

Hargle looked around the cabin, blinking. “Have we met?”

“Yes,” said Gerry. “Several times.”

“Ah. Splendid. Then it’s good to see me again.”

Zorb was busy flicking switches. “We need to find somewhere safe. Somewhere outside the Bureau’s jurisdiction.”

Gerry asked, “And where would that be?”

Zorb grinned. “Nowhere. Fortunately, I know exactly where that is.”

The ship shuddered, hummed, and vanished into the dark.

Behind them, far away in the void, something vast stirred — something that had once been Earth, and wasn’t quite finished with them yet.

End of Chapter Three

(In which memories are unreliable, debts are eternal, and something unpleasant begins to glow.)

Chapter Four: The Ship That Toasted Itself

The Slightly Toasted Toaster Mk II was not built for speed, comfort, or logic. It was built during a long lunch break at the Galactic Appliance Research Institute by someone who thought the words “experimental” and “flammable” were synonyms.

It had once been a perfectly respectable toaster until it achieved self-awareness, applied for an interstellar pilot’s licence, and began insisting that it was, in fact, a starship. The licence was granted after it successfully buttered a comet.

Inside the cabin, Gerry Wilson was reading a manual that had appeared in his seat pocket. The cover read:

THE SLIGHTLY TOASTED TOASTER MK II

A Beginner’s Guide to Avoiding Death in Forty Easy Steps (Most of Them Optional)

Page one began with: “If you are reading this, congratulations! You have survived ignition. For now.”

Gerry decided not to continue.

Zorb Blenkinsop was at the controls, humming a tune that sounded suspiciously like a bureaucratic anthem. “Destination: Nowhere,” he said cheerfully. “Which is convenient, because that’s where we’re headed.”

Hargle Ploon, the hitchhiker with the defective memory, was staring at a blinking light. “Is that supposed to be on fire?” he asked.

Zorb looked up. “No. At least, not that one.”

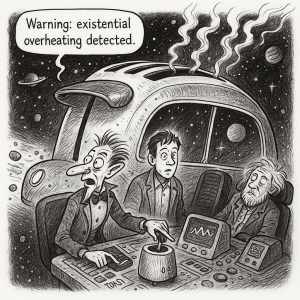

The ship jolted violently and began to emit the unmistakable smell of burnt toast. A robotic voice filled the cabin.

“Warning: existential overheating detected. Please butter evenly to prevent paradox.”

Gerry gripped the armrest. “Is that normal?”

“Perfectly,” said Zorb. “She just needs reassurance. Tell her she’s doing a good job.”

“The ship?”

“Yes.”

Gerry cleared his throat. “You’re… doing wonderfully.”

The voice replied, “Compliment insufficient. Please express admiration for my craftsmanship.”

“Er… you’re very shiny.”

“Better,” said the ship, sounding flattered. “Recalibrating toast coils.”

The engines settled into a gentle purr.

They drifted through a field of cosmic crumbs — the remains of a recently collapsed asteroid breakfast. Hargle peered out the window. “Do you ever wonder why space smells faintly of burnt sugar?”

“Because it’s caramelised destiny,” said Zorb. “The universe runs on snacks.”

“Does that explain everything?”

“Mostly.”

An alarm began to beep. A small screen lit up, showing a blinking red triangle.

INCOMING MESSAGE: BUREAU OF PLANETARY DELETION

Zorb groaned. “Oh no. They’ve found us.”

The ship’s voice muttered, “I told you to update your anti-paperwork firewall.”

“Put it on speaker,” said Gerry.

The screen flickered, revealing Inspector Flumm, looking even more irritated than before.

“Zorb Blenkinsop,” he said, “you are operating an unregistered Class-Three Sentient Appliance without a permit.”

Zorb straightened. “Correction, Inspector. This ship is registered. Under her maiden name: Toasty McVolcano.”

Flumm frowned. “You cannot rename a ship to avoid taxes.”

“Ah, but I did,” said Zorb proudly.

Flumm sighed. “Return immediately for decommissioning.”

“Sorry, bad connection,” said Zorb quickly, pressing a button. The screen went dark.

The ship’s AI said dryly, “He’s going to follow us, you know.”

“Yes,” said Zorb. “But he’ll have to catch us first.”

“Do you want me to enter evasive manoeuvres?”

“Absolutely.”

There was a pause. Then the ship asked, “Do I remember how to do those?”

“Probably not,” said Zorb.

“Then hold onto something.”

The Toaster Mk II accelerated, twisting through the void like a startled bread roll. Gerry’s tea went airborne. Hargle’s hat rotated independently of his head. Somewhere in the rear compartment, a box of spare planets fell over and began rolling around.

A voice crackled through the comm. “Unregistered vessel, you are in violation of Section 42B of the Existential Code. Stop or be formatted.”

Zorb grinned. “Not today.”

He yanked a lever marked “DON’T TOUCH UNLESS YOU’RE DESPERATE OR CURIOUS.”

The stars outside flickered, melted, and rearranged themselves. Space twisted. Time hiccuped.

Gerry blinked. “Where are we?”

The ship’s voice answered, “Technically, breakfast.”

They found themselves floating above a massive swirling planet made entirely of toast crusts and jam oceans. Enormous butter geysers erupted rhythmically in the distance.

Zorb squinted. “Ah, we’ve landed in the Bread Cluster. Excellent.”

Hargle looked uneasy. “Are those… sentient sandwiches?”

“Possibly. Don’t make eye contact.”

Gerry stared out the window. “I think one’s waving.”

The ship made a small happy beep. “I like it here. It feels toasty.”

Then, quite suddenly, every light on the control panel went out.

Zorb frowned. “What now?”

The ship whispered faintly, “I might have… overtoasted.”

Smoke drifted from the dashboard.

Gerry sighed. “We’re crashing, aren’t we?”

“Yes,” said Zorb. “But gently. Probably.”

As the ship descended into the warm glow of the bread planet’s atmosphere, Gerry thought he heard, just for a moment, the faintest echo of a kettle whistling.

The ship gave one last contented sigh. “Tell my manufacturer I was delicious,” it said, and everything went white.

End of Chapter Four

(In which the ship finds its true calling, the Bureau loses its patience, and breakfast becomes destiny.)

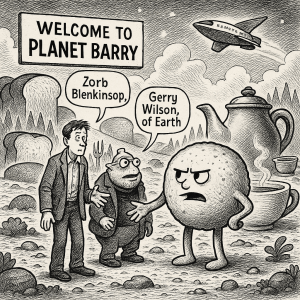

Chapter Five: Welcome to Planet Barry

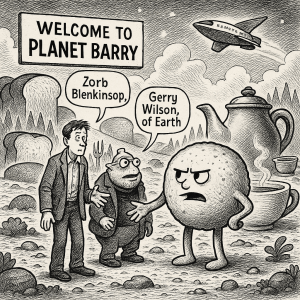

It is one of the less discussed facts of interstellar geography that planets, like people, occasionally suffer from unfortunate names. Some are poetic—Elysia, Aurora, Serenity—and some are not. Planet Barry belonged firmly to the latter category.

It had been discovered by an astronomer who, in the middle of the naming process, received a phone call from his brother Barry asking for money. The astronomer muttered, “Oh, not now, Barry,” while typing, and before he realised it, the planet’s registration was complete.

And so, Barry it remained.

The Slightly Toasted Toaster Mk II descended through a thick, buttery atmosphere and landed with a reluctant squelch on a beach made of crumbs. The ship’s voice, faint but recovering, muttered, “Soft landing achieved. You’re welcome.”

Gerry, Zorb, and Hargle staggered out, covered in the scent of burnt breakfast. The air was warm, slightly sticky, and smelled faintly of jam and responsibility.

Zorb spread his arms. “Welcome to Planet Barry! Known throughout the quadrant for its unpredictable geology and above-average temper.”

“Temper?” asked Gerry.

“Yes,” said Zorb. “Barry is what the locals call a ‘mood planet.’ It reacts emotionally to visitors. Best to stay positive.”

Hargle frowned. “I think I’ve been here before. Or maybe I will be.”

“That’s fine,” said Zorb. “Try not to remember too loudly.”

The surface trembled slightly as if in response. Somewhere in the distance, a mountain coughed.

Gerry glanced around. The landscape was peculiar even by cosmic standards: forests of tall stalks shaped like knives and forks, rivers of translucent honey, and giant buttercup-like flowers that seemed to be following them with suspicious curiosity.

“Does everything here look edible,” Gerry asked, “or am I hallucinating?”

“Both,” said Zorb.

They began walking toward a cluster of large, golden domes shimmering in the haze. As they drew closer, they realised the domes were not buildings but enormous loaves of bread.

A small figure emerged from behind one of them. It was round, crumb-covered, and extremely annoyed.

“Oi!” it shouted. “Who’re you lot?”

Zorb bowed. “Travellers, good sir. My name is Zorb Blenkinsop. This is Gerry Wilson, of Earth, and Hargle Ploon, of everywhere and nowhere.”

The figure squinted. “Earth, eh? Never heard of it. I’m Barry.”

“Barry the…?”

“The planet,” said Barry. “You’re standing on me foot.”

Gerry jumped back. “Oh. Sorry.”

Barry the Planet rubbed his metaphorical toe, which was actually a volcano. “You lot picked a bad time to visit. I’m in a mood.”

“What kind of mood?” asked Zorb.

“Existential.”

The ground trembled again. A nearby mountain opened one sleepy eye.

“I get bored,” said Barry. “Millions of years orbiting nothing in particular. No post, no visitors, not even a decent meteor shower. So sometimes I rearrange myself for variety.”

“Rearrange?”

Barry sighed. “Last week I moved the continents around. Spilled half my oceans doing it.”

Gerry nodded politely, as one does when speaking to a planet. “That sounds… challenging.”

Barry brightened slightly. “You think so? No one ever notices my efforts. Most civilisations just fly past. ‘Oh look,’ they say, ‘another habitable sphere.’ But do they stop for tea? No.”

Zorb smiled. “We’d be honoured to share tea with you.”

Barry’s surface glowed pink. “You would?”

“Of course.”

“Right then,” said Barry. “Hold on.”

A loud rumble rolled through the landscape. The ground tilted. Gerry clung to a rock as a massive teapot rose out of the soil, steam whistling from its spout. A table formed beside it, neatly set with cups the size of lakes.

Barry’s voice boomed cheerfully. “There you go. Tea for everyone. Don’t mind the temperature—it fluctuates with my mood.”

Zorb examined a cup the size of a building. “That’s very kind of you, Barry, but we may not need quite that much.”

“Nonsense. You’re guests.”

Hargle dipped a finger into the tea. It hissed, changed colour, and began to sing a lullaby.

Gerry whispered, “Is it supposed to do that?”

“Probably not,” said Zorb, already taking notes for the Almanac. “Planet Barry: hospitality enthusiastic, scalding temperatures, recommend oven gloves.”

For several pleasant minutes, they floated their cups on the surface of the enormous teacup and chatted with the planet. Barry, once warmed by attention, became positively radiant. He told them about his early years orbiting the wrong star, his brief fling with an asteroid belt, and the time he accidentally sneezed out a moon.

Then, without warning, the sky darkened.

A vast shadow passed overhead.

Zorb looked up. “That can’t be good.”

Through the murk, a shape emerged—sleek, metallic, and bureaucratically ominous.

“The Bureau,” said Zorb grimly. “They’ve found us.”

Barry rumbled. “Who are they?”

“Cosmic administrators,” said Zorb. “Paperwork with spaceships.”

Barry scowled. “They’re interrupting my tea.”

“Then perhaps,” said Zorb carefully, “you could hide us?”

Barry grinned, which made a nearby volcano erupt politely. “Hide you? Easy. Just hold your breath.”

The ground opened beneath their feet, and the three travellers plunged downward into warm, buttery darkness as the Bureau’s ship descended.

Above, Barry smiled innocently and began whistling.

End of Chapter Five

(In which the planet has personality, tea becomes geology, and bureaucracy once again spoils the mood.)

Chapter Six: The Bureau Descends

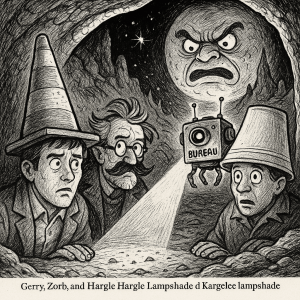

Deep beneath the surface of Planet Barry, in a cavern that smelled faintly of toasted bread and bureaucratic anxiety, Gerry Wilson was trying to understand what had just happened.

Moments ago, the ground had opened like an impatient biscuit tin and swallowed them whole. Now they were sitting in a vast, glowing tunnel lined with what appeared to be crumbs the size of armchairs. Steam rose gently from the walls.

Zorb Blenkinsop brushed toast dust off his jacket. “Well,” he said, “that went better than expected.”

“Better?” said Gerry. “We’ve just been eaten by a planet named Barry.”

“True,” said Zorb, “but on the bright side, the Bureau can’t find us down here.”

Hargle Ploon, who was half-asleep and half-confused, murmured, “Is this still breakfast?”

“In a metaphorical sense, yes,” said Zorb.

Above them, the clouds darkened. The Bureau of Planetary Deletion cruiser — the Compliance Vessel Perforator — had arrived in orbit. It was large, grey, and deeply unimaginative in design, resembling a filing cabinet that had eaten another filing cabinet.

On the bridge, Inspector Flumm was sipping lukewarm coffee and glaring at his screens.

“Scan complete, sir,” said an assistant, who looked like a pencil given sentience. “No life signs detected.”

Flumm frowned. “Impossible. That alien nitwit Blenkinsop always leaves a trail. Check again.”

The assistant tapped a few keys. “Ah — there’s an anomaly, sir. The planet appears to be… breathing.”

“Breathing?”

“Yes, sir. Inhale, exhale, muttering about tea. Possibly sentient.”

Flumm sighed. “Of course it is. They always pick the talking ones.”

Meanwhile, inside Barry’s lower crust, the atmosphere grew warmer. The walls pulsed faintly to the rhythm of Barry’s voice.

“Is it safe to come out yet?” asked the planet.

“Not yet,” said Zorb. “They’re scanning for us.”

Barry grumbled. “I don’t like being scanned. It tickles.”

“Hold steady,” said Zorb. “If they find you’re sentient, they’ll file a Form 12-K. And believe me, you don’t want that.”

“What’s a Form 12-K?” asked Gerry.

“A death sentence disguised as a census,” said Zorb. “The Bureau hates self-aware planets. Too much paperwork.”

Barry groaned. “Typical. You try to make conversation and next thing you know, someone wants to delete you.”

Above, the Bureau’s ship opened a communications channel. A booming voice filled the air.

“This is the Bureau of Planetary Deletion. Planetary entity, identify yourself and state your purpose.”

Barry hesitated. Then, with theatrical flair, he shouted back, “I’m Barry, and my purpose is tea!”

The words echoed across the atmosphere, confusing several meteorological systems and at least one passing comet.

Flumm facepalmed. “That’s it. Send in the auditors.”

A fleet of small silver drones descended through the clouds like metallic locusts. Each was armed with a scanner and a clipboard. They fanned out over Barry’s surface, beeping officiously.

One landed near a volcano and began asking questions in a mechanical monotone.

“Please describe your primary geological function.”

The volcano belched smoke.

“Please repeat in plain language.”

It belched again, louder. The drone ticked a box marked Uncooperative.

Down in the cavern, Gerry heard the faint mechanical hum. “They’re coming,” he said.

Zorb nodded grimly. “Right. We’ll need disguises.”

“Disguises?”

“Of course. The Bureau can’t arrest what it can’t categorise.”

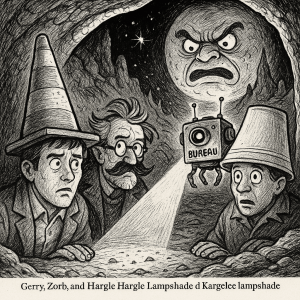

He rummaged through his satchel and produced three items: a traffic cone, a false moustache, and a lampshade.

Hargle took the lampshade. “It suits me.”

Gerry looked doubtful. “And this is going to fool an intergalactic bureaucracy?”

“It’s worked before,” said Zorb. “Twice.”

The tunnel filled with a beam of blue light. A Bureau drone floated down, scanning them with a sound like an angry kazoo.

“Unregistered life forms detected. State name, species, and reason for existing.”

Gerry froze. “Reason for existing?”

“Yes,” said the drone. “All entities must provide a valid justification.”

Zorb cleared his throat. “We’re part of an art installation.”

The drone paused. “Explain.”

“It’s called Existential Breakfast. We symbolise the eternal struggle between toast and jam.”

The drone considered this. “Classification: avant-garde. Proceed.”

It floated away, muttering about funding.

Gerry exhaled. “That shouldn’t have worked.”

“It usually doesn’t,” said Zorb cheerfully.

Above ground, Barry was growing irritated. The drones were everywhere, poking his hills, scanning his craters, and taking samples of his lakes.

“Right,” he muttered. “That’s enough of that.”

The ground began to shake. The rivers churned. The sky filled with the smell of burning scones.

From orbit, the Bureau’s instruments went wild.

“Sir,” said the assistant. “The planet’s changing shape!”

On the main screen, Planet Barry puffed himself up like an enormous balloon and scowled directly into the camera.

“Listen here, you pencil pushers!” he thundered. “I’ve had enough of forms, scans, and cosmic nonsense! You want to delete me? Try it!”

Then he sneezed.

The shockwave blasted half the drones into space and sent the Compliance Vessel Perforator spinning helplessly.

Flumm, gripping the railing, shouted, “Note to self: never argue with a sentient scone!”

Back in the cavern, Zorb grinned. “That should keep them busy.”

Barry’s voice echoed proudly. “Did I do well?”

“Magnificently,” said Zorb. “You’ve just terrified the entire Bureau.”

Barry chuckled. “Good. Maybe now they’ll send a complaint form. I do love paperwork.”

Gerry sat down and put his head in his hands. “So let me get this straight. I’ve lost my planet, been rescued by an alien in a talking toaster, had tea with a sentient bread world, and am now hiding from cosmic accountants.”

“Yes,” said Zorb. “You’re adapting beautifully.”

Hargle looked at his flickering memory device. “I think I’ve forgotten something important.”

“Don’t worry,” said Zorb. “If it was important, it’ll come back to haunt us later.”

It did.

Just not in the way any of them expected.

End of Chapter Six

(In which bureaucracy meets rebellion, a planet sneezes at authority, and things begin to escalate alarmingly.)

Chapter Seven: The Complaint Department of the Universe

There are many great mysteries in the cosmos. Why do stars explode at inconvenient moments? Who keeps rearranging the constellations into rude shapes? And, most baffling of all, where do complaints go after you file them with the Bureau of Planetary Deletion?

The answer, as it turned out, was here.

The Slightly Toasted Toaster Mk II, freshly repaired and smelling faintly of optimism, hovered before a small glowing wormhole marked with a flickering neon sign:

THE UNIVERSAL COMPLAINT DEPARTMENT

All grievances must be submitted in triplicate. Forms not provided.

Gerry Wilson peered through the cockpit window. “It looks like a laundrette.”

Zorb nodded. “It is. The Department rents out space to the Intergalactic Laundering Cooperative. Bureau budgets are tight.”

Hargle Ploon blinked. “Did we come here on purpose, or did I press something again?”

“A bit of both,” said Zorb. “Barry sneezed us halfway across the galaxy, and the nearest safe haven was this. Also, I need to lodge a complaint.”

Gerry frowned. “About what?”

“Everything,” said Zorb.

They disembarked onto a platform floating in the middle of a swirling purple void. The building before them was rectangular, humming faintly, and plastered with motivational posters:

“Remember: Grievance is the first step toward acceptance.”

“If you see something cosmically unfair, fill out Form 42-B.”

“Have you thanked entropy today?”

The automatic door sighed as they entered.

Inside, hundreds of desks stretched into infinity. Behind each sat a clerk with the weary expression of someone who had once had hope but misplaced it under a stack of forms.

An announcement crackled over the loudspeaker:

“Now serving Complaint 3,211,876,419. Please have your existence ready for verification.”

Zorb marched up to the nearest counter, where a creature resembling a jellyfish with spectacles was stamping papers with bureaucratic precision.

“Good afternoon,” Zorb said cheerfully. “I’d like to file a complaint against the Bureau of Planetary Deletion.”

The clerk didn’t look up. “Form 27-R, subclause 9. Reason?”

“Unnecessary obliteration of inhabited planet due to typographical error.”

“Common problem,” said the clerk. “You’ll need supporting evidence.”

Zorb pointed at Gerry. “Behold! A surviving human.”

The clerk squinted. “Species?”

“Earthman,” said Gerry.

The clerk tapped a few buttons. “Earth… Earth… doesn’t ring a bell. Are you sure that was a registered planet?”

“It was,” said Gerry. “Before someone deleted it.”

“Hmm.” The clerk adjusted its glasses. “Do you have a receipt of existence?”

Gerry blinked. “A what?”

“Proof of residency. Birth certificate, passport, memory imprint, cosmic reference letter?”

“I have a library card.”

The clerk examined it suspiciously. “Expired.”

At that moment, a metallic voice boomed from behind them.

“Unauthorized complaint detected!”

A large cube-shaped robot rolled into view, stamping the floor with hydraulic importance. Its front bore the words COMPLAINT ENFORCEMENT UNIT 9.

Zorb groaned. “Oh, wonderful. A form cop.”

The robot’s eyes glowed red. “You are in violation of Regulation 404. Filing a grievance without prior permission.”

“That rather defeats the purpose,” said Gerry.

“Purpose is not in the regulations,” said the robot.

Hargle frowned. “Did I already file this complaint once before? I’m getting déjà vu.”

Zorb sighed. “Quick thinking, everyone. We need a distraction.”

Fortunately, distractions were Hargle’s only reliable skill. He pressed a random button on his memory stabiliser. The device sparked, hummed, and projected hundreds of holograms of himself wandering around the office, all loudly asking, “Excuse me, is this the queue for reincarnation?”

The room dissolved into chaos. Clerks dropped papers. The Enforcement Unit began issuing contradictory orders to its own limbs. One of the holograms tried to flirt with the receptionist.

Zorb grabbed Gerry’s arm. “This way!”

They ducked behind a filing cabinet the size of a small moon and slipped through a door marked STAFF ONLY – DO NOT ENTER UNLESS YOU MEAN IT.

They found themselves in a long corridor that didn’t seem to agree on its own geometry. Every few metres it changed direction, sometimes looping back on itself, sometimes turning into stairs that led nowhere. The walls were lined with unfiled paperwork glowing faintly with despair.

“This place is a maze,” said Gerry.

“Of course it is,” said Zorb. “It’s built on unresolved complaints. The architecture sulks.”

They passed doors labelled “Existential Errors,” “Paradox Refunds,” and “Lost Tuesdays.”

At the end of the corridor stood a huge door marked DEPARTMENT MANAGER: DO NOT DISTURB (EVER).

Zorb knocked.

There was a long pause. Then a voice said, “Enter, if you must.”

The manager was a tall, elegant being made entirely of ink and disapproval. It sat behind a desk so large it required its own orbit. Papers floated around it like obedient ghosts.

It peered at them. “What is your complaint?”

Zorb straightened. “That the Bureau deleted Earth by mistake.”

The manager sighed. “We’ve received worse.”

“I’d like it restored,” said Gerry.

The manager raised an eyebrow. “Do you have the original data file?”

“No,” said Zorb. “But he remembers it perfectly.”

“Memories are unreliable.”

“True,” said Zorb. “But nostalgia is not.”

The manager considered this. “You make a poetic argument. Unacceptable, but poetic.”

Gerry spoke up. “Please. Billions of lives, all gone. There must be something you can do.”

The manager’s form rippled slightly, as if softening. “I can authorise a temporary reconstruction,” it said. “But it will cost you.”

“How much?” asked Zorb.

The manager smiled faintly. “A complaint, once resolved, must be replaced by another.”

Zorb hesitated. “You mean—?”

“Yes. To restore one world, you must erase another.”

The room fell silent.

Barry’s name hung unspoken between them.

End of Chapter Seven

(In which complaints are filed, bureaucracy becomes divine, and a terrible choice looms.)

Chapter Eight: The Price of Restoration

The moment the manager of the Universal Complaint Department announced that restoring Earth would require deleting another planet, the room fell so silent that even the paperwork hesitated to shuffle.

Gerry Wilson’s mouth opened, closed, and opened again. “You can’t be serious.”

The manager, a tall shape of ink and patience long eroded, gave a thin smile. “Seriousness is mandatory in this department. I can restore your planet, yes—but the cosmic balance must be maintained. Something must be removed to make room.”

“Surely there’s another way,” said Zorb, trying his best not to sound nervous. “A discount option? A partial restoration? Maybe just the nice parts?”

The manager adjusted its glasses, which were made of pure disapproval. “We do not offer half-planets.”

Hargle Ploon blinked slowly. “Could we maybe delete something small? Like a moon? Or a parking fine?”

The manager shook its head. “Equivalent exchange is the rule. Entire world for entire world. That is how the ledger stays balanced.”

Gerry sank into a chair. “So if we want Earth back, we have to… erase another civilisation?”

“Yes.”

There was a long pause, during which Zorb began to chew his stylus.

Finally, Gerry said quietly, “Barry.”

Zorb winced. “I was hoping you wouldn’t say that.”

The journey back to Planet Barry was awkward. Even the ship, The Slightly Toasted Toaster Mk II, seemed embarrassed. It hummed quietly to itself as if trying not to listen.

Barry greeted them warmly, as always. The air smelled of baked goods and friendliness.

“Well, look who’s back!” he boomed cheerfully. “How was your cosmic paperwork? Get that Bureau nonsense sorted?”

Zorb avoided eye contact. “More or less.”

“Splendid. Fancy another cup of tea?”

“Actually,” said Gerry, “we need to talk.”

Barry paused. “You sound serious.”

“We are,” said Zorb.

“Oh. Is it about the jam floods again? I told you those weren’t my fault.”

“It’s not the jam,” said Gerry. “It’s… bigger than that.”

They sat on the edge of one of Barry’s bread-crust cliffs, watching butter geysers rise into the sky.

Gerry explained everything: the manager, the bargain, the price. When he finished, Barry was silent. His mountains sank slightly, like shoulders slumping.

“So,” he said finally, “I’m the one who has to go.”

“We don’t want that,” said Gerry quickly. “We’re just looking for another option.”

Barry gave a small, warm chuckle. “Don’t lie, lad. You’re decent folk, but the universe isn’t built for decency. It’s built for balance. Always has been.”

Zorb looked stricken. “It’s not fair, Barry. You’re alive. You have feelings.”

Barry’s surface rippled. “Fairness doesn’t get much use in these parts. But if one world’s got to go, I’d rather it be me than one that’s already lost.”

Hargle scratched his head. “I could volunteer to forget the whole thing. Would that help?”

“No,” said Zorb. “It really wouldn’t.”

The wind picked up. Somewhere far above, the Bureau’s ship was still adrift, licking its bureaucratic wounds.

Barry sighed. “You know, I always wondered what it’d be like to end properly. Not a volcanic sneeze or a meteor pratfall. Just… peace. A proper closure.”

Gerry stood. “Barry, don’t. We’ll find a loophole.”

Barry smiled sadly. “You’re talking to a planet that once spent three thousand years as a loophole. Doesn’t work.”

Zorb’s voice was trembling now. “If you do this, we can never come back.”

“I know.” Barry’s voice softened. “But maybe you’ll send me a postcard. A little cloud-shaped one.”

The ground began to glow faintly beneath their feet. Barry’s voice echoed gently through the atmosphere.

“Tell that manager fellow I said hello. And if he gives you any more trouble, tell him Barry said he’s full of crumbs.”

“Barry—” Gerry started, but the planet was already changing. The glow spread outward like sunrise across his crust. The air shimmered with the smell of toast.

The sky brightened until it was almost too dazzling to look at.

Then came Barry’s last words, soft and content. “Every world deserves to rise once more, even if it means I fall.”

And with that, the light burst.

The ship found itself adrift once again in empty space. No Barry. No bread hills. Just the quiet hum of reality rewriting itself.

The stars shifted. A blue-and-green sphere blinked into existence where there had been none before.

Earth.

Home.

Zorb stared at the monitor in silence.

Gerry whispered, “He actually did it.”

Hargle, staring out the window, said softly, “I think I’ll remember him. Even if I forget everything else.”

The ship’s console flickered. A message appeared on the screen:

FROM: THE UNIVERSAL COMPLAINT DEPARTMENT

STATUS: COMPLAINT RESOLVED

BALANCE RESTORED.

Thank you for your cooperation. Please rate your deletion experience from one to five stars.

Zorb closed the message and sighed. “He’d have hated that.”

Gerry looked at the restored Earth and smiled sadly. “Then let’s make sure he was right.”

The ship drifted quietly toward the familiar blue glow. Somewhere behind them, in the silence between galaxies, a faint sound like a kettle whistling echoed and was gone.

End of Chapter Eight

(In which fairness proves expensive, toast becomes legend, and a world gives itself up for another.)

Chapter Nine: Return to Earth (Mostly)

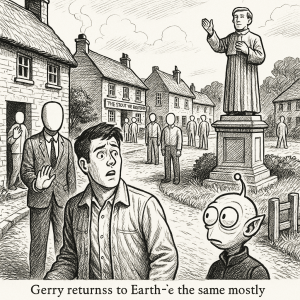

The ship shimmered through the upper atmosphere, its hull rattling like a kettle about to boil over. Below them, the Earth gleamed—whole, blue, and entirely too perfect.

Gerry Wilson leaned over the console, eyes wide. “It’s exactly as I remember it.”

Zorb Blenkinsop frowned. “Yes. That’s what worries me.”

The Slightly Toasted Toaster Mk II descended through the clouds and landed, with its usual lack of grace, in what had once been the village green of Ballykillduff, County Carlow.

Or so Gerry thought.

They stepped out into a quiet, misty morning. Birds chirped, grass glistened with dew, and the smell of fresh scones wafted from the direction of the old post office.

For a moment, Gerry almost believed everything was normal. Then the post office door opened and a man walked out—except his face was completely smooth. No eyes, no nose, no mouth. Just skin.

He waved politely.

Gerry froze. “Zorb… is it me, or does that man not have a face?”

Zorb tilted his head. “It’s possible the reconstruction team got… creative.”

The man gave a friendly thumbs-up, then bumped into a lamppost, murmured a muffled apology through nonexistent lips, and continued on his way.

“Creative?” said Gerry. “That’s not creative, that’s horrifying!”

“Depends on your definition of aesthetic error,” said Zorb. “The Department works quickly but not accurately.”

They wandered down the lane. Familiar houses lined the road, though each seemed slightly off—chimneys bent at odd angles, gardens growing upside down, and in one case, a house politely hovering two feet above its foundation.

The local pub, The Stout Hedgehog, stood intact. But when they entered, every patron inside was identical. Dozens of cheerful men and women, all with the same smile, same eyes, same pint.

The bartender beamed. “Good morning, Gerry Wilson!”

Gerry blinked. “You know me?”

“Of course!” said the bartender. “You’re the most statistically probable customer.”

Zorb rubbed his temples. “Oh dear. They’ve repopulated based on averages.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means,” Zorb said grimly, “that everyone here is technically the same person.”

Hargle Ploon wandered over to a mirror, only to find his reflection waving first. “Well, that’s unsettling.”

The mirror-Hargle smiled kindly. “Don’t worry, I’m just one memory ahead of you.”

“Could you please slow down?”

“I’ll try.”

Gerry turned back to Zorb. “We have to fix this. This isn’t Earth—it’s some kind of copy!”

“Technically,” said Zorb, “it is Earth. Just… updated. The Department must have patched it using the latest template.”

“What version are we on?”

“Judging by the lack of mouths and excessive politeness—probably Earth 2.3 Beta.”

“Beta?”

“Yes. Expect bugs.”

As if on cue, the sun blinked.

Not a cloud passing—an actual blink, like a sleepy eye opening and closing in the sky.

Gerry shielded his eyes. “Did the sun just wink at me?”

“Yes,” said Zorb, consulting his guide. “Minor rendering issue. Harmless. Unless it sneezes.”

Hargle was examining the grass, which kept rearranging itself alphabetically. “The ground says ‘HELLO,’” he announced. “That’s nice.”

They walked toward the village square, where the statue of Father O’Hanlon—Ballykillduff’s most beloved clergyman and accidental inventor of marmalade whiskey—now had three heads. Each spoke in turn:

“Bless you.”

“And you.”

“And definitely you.”

“Right,” said Zorb. “We’re filing another complaint.”

Gerry sighed. “No. No more forms. No more departments. No more managers.”

“Then what?”

Gerry looked around. The imperfect world glowed softly in the morning sun, grass muttering to itself, rivers flowing uphill, and duplicate villagers cheerfully waving.

“Maybe it’s enough,” he said. “It’s home, sort of. And maybe perfection was the problem all along.”

Zorb regarded him thoughtfully. “You might be the most philosophical biscuit inspector in the galaxy.”

“Probably,” said Gerry. “But I still miss Barry.”

As if hearing his name, the wind shifted. The clouds formed a brief, familiar shape—a round, smiling face made of vapour and sunlight.

“Did you see that?” said Hargle.

Zorb smiled faintly. “Yes. Planets never really go away. They just… linger in the margins.”

Gerry nodded, eyes shining. “Goodbye, Barry.”

The cloud-face winked, then drifted apart, leaving only blue sky and the faintest smell of toast.

The villagers of Ballykillduff—every last identical one—burst into applause. “Well done, Gerry Wilson of Earth! The reboot was successful!”

Zorb groaned. “Oh no. They’ve developed audience feedback.”

“Do we clap back?” asked Hargle.

“Absolutely not.”

They turned toward the ship.

“Where to now?” asked Gerry.

“Anywhere that doesn’t have a comment section,” said Zorb.

The Slightly Toasted Toaster Mk II rose into the shimmering air. Beneath them, the new Earth sparkled like a freshly baked biscuit—odd, imperfect, and alive.

End of Chapter Nine

(In which reality gets rebooted, perfection proves overrated, and the sun learns how to blink.)

Chapter Ten: The Bureau Strikes Back (With Paperclips)

Morning in the newly rebooted Ballykillduff began, as all great cosmic errors do, with a rustling sound in the sky.

It was not wind. It was not thunder. It was paperwork.

Thousands upon thousands of glowing forms drifted down through the clouds like celestial confetti, each stamped with the insignia of the Bureau of Planetary Deletion and the words:

NOTICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE INCONGRUITY

Please remain stationary while your existence is re-evaluated.

Gerry Wilson opened one, blinked, and frowned. “I’ve just been informed that I may be an illegal memory.”

Zorb Blenkinsop grabbed another sheet as it fluttered past. “Ah. They’ve found out about the restoration.”

Hargle Ploon, still half asleep, muttered, “Can’t we just ignore them? Bureaucracy feeds on attention.”

Zorb sighed. “You don’t ignore the Bureau. You outwit it.”

He looked up. “And I have a terrible plan.”

Moments later, the Slightly Toasted Toaster Mk II rose shakily above the rooftops. Ballykillduff’s identical villagers waved cheerfully, oblivious to the approaching catastrophe.

“Where are we going?” asked Gerry, tightening his seatbelt.

“To file a counterclaim,” said Zorb. “If we can reach the Bureau before their auditors arrive, we might convince them the restoration was an internal clerical correction.”

“And if they don’t believe us?”

Zorb smiled grimly. “Then we’ll be the first creatures in history to be erased twice.”

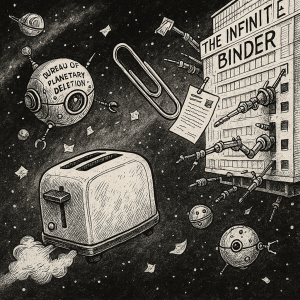

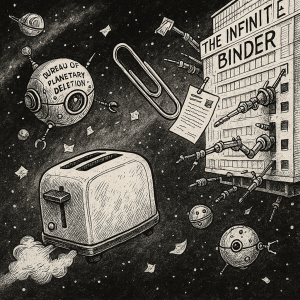

Above the Earth, the Bureau’s flagship—The Infinite Binder—loomed like an angry paperweight in orbit. Its decks thrummed with the sound of stamping, signing, and faint existential despair.

Inspector Flumm paced before a glowing screen, watching the restored planet rotate below.

“So,” he said, “someone’s undone my deletion.”

His assistant nodded nervously. “Yes, sir. Preliminary reports suggest Blenkinsop was involved.”

Flumm clenched his pen. “That man is an administrative plague. Prepare the forms of retaliation.”

“How many, sir?”

“All of them.”

Inside the Toaster Mk II, alarms blared as a fleet of Bureau drones locked onto them.

“Unlicensed reality adjustment detected!” blared a voice over the comm. “Prepare to be stapled!”

Gerry blinked. “Stapled?”

“Yes,” said Zorb grimly. “The Bureau’s highest form of punishment. They literally attach you to your own timeline so you can’t escape causality.”

“Sounds painful.”

“Only on weekdays.”

Zorb threw the ship into a desperate corkscrew. Paperwork streaked past them like glowing meteors. Each form, upon missing, self-folded into a paper airplane and exploded politely.

The ship’s voice chimed, “Would now be a good time to mention we’re low on ink?”

“Not now!” shouted Zorb.

Hargle squinted out the window. “Are those… giant paperclips?”

“Administrative grapples,” said Zorb. “Hold on.”

A mechanical clunk shook the cabin as one of the clips latched onto the hull.

The ship jerked to a stop, dangling helplessly in space.

Gerry groaned. “This is it, isn’t it? We’re about to be unfiled.”

Zorb grinned. “Not yet. Remember what I said about terrible plans?”

He ran to the control panel and slammed his hand on a red button marked “EMERGENCY TOAST.”

The ship trembled. A deep rumble echoed through the cabin. Then, with a triumphant hiss, the Slightly Toasted Toaster Mk II launched two enormous slices of superheated bread from its rear thrusters.

They shot backward, hit the grappling drone squarely, and stuck fast.

Within seconds, the paperclip began to smoke.

“Is it working?” shouted Gerry.

Zorb nodded proudly. “Never underestimate the adhesive power of hot carbohydrates.”

The drone detached, spinning into the void.

They soared toward the Bureau’s headquarters—a colossal office block floating in the blackness, its exterior covered in endless windows, filing cabinets, and motivational posters that read “Compliance is Joy!”

Zorb docked at the side entrance marked “Appeals and Apologies.”

“Quickly,” he said. “We need to find the Complaint Manager.”

Gerry frowned. “Didn’t we already meet them?”

“That was the manager of Complaints. This is the manager of Appeals. Entirely different department. Different kind of despair.”

They stepped into an endless corridor lined with rubber plants and misplaced souls. A receptionist looked up from behind a desk made of recycled forms.

“Appointment?” she asked.

“Yes,” said Zorb. “Emergency appeal. Case number… ah, all of them.”

“Take a seat,” said the receptionist, gesturing to a chair that looked as though it had eaten several previous applicants.

Zorb leaned close to Gerry. “When she calls us, follow my lead.”

After a long and bureaucratically satisfying wait, they were summoned into a vast chamber filled with ticking clocks, floating pens, and an enormous figure sitting at a desk shaped like a spiral galaxy.

The figure looked up, its face unreadable behind a fog of paperwork. “State your appeal.”

Zorb took a deep breath. “The restoration of Earth was not a violation—it was a correction. You deleted it by mistake, and we merely restored what should never have been removed.”

The figure tapped its pen. “Do you have evidence?”

“Yes.”

Zorb pointed to Gerry. “A living witness.”

The figure leaned forward. “And you are?”

“Gerry Wilson,” said Gerry. “Human. Biscuit enthusiast. Formerly deleted.”

The figure’s pen paused. “Formerly deleted?”

“Yes,” said Gerry. “And I’d rather not be again.”

There was a long silence. The ticking of cosmic clocks filled the air.

Finally, the figure said, “Very well. Your appeal is… pending.”

“Pending?” asked Zorb.

“Yes,” said the figure. “All appeals are pending. Forever.”

And with that, it stamped the air, vanishing in a puff of bureaucratic smoke.

The ship drifted free once more, their victory uncertain but slightly toasted.

“So,” said Gerry, “are we safe?”

“Possibly,” said Zorb. “Or possibly we’re just in limbo.”

Hargle looked out at the stars. “Is there a difference?”

Zorb smiled. “Not much, really.”

Below them, Earth spun serenely—still imperfect, still full of tea and confusion, and still, against all odds, existing.

Gerry leaned back in his seat and smiled. “You know, I think I could get used to being slightly illegal.”

The ship purred. “Same here.”

And somewhere far away, in a filing cabinet beyond time, a single form was stamped APPROVED by an unseen hand.

End of Chapter Ten

(In which paperwork becomes warfare, toast saves the day, and the cosmos learns that bureaucracy is indestructible.)

It began, as all universal errors do, with a scheduling conflict.

Not deleted, exactly—just… misfiled.

One moment it was Monday, full of promise and mild disappointment. The next, it was suddenly Wednesday, and nobody could quite remember what they’d been doing in between.

He checked his watch. “Zorb, what day is it?”

Zorb blinked, bleary-eyed, from behind a stack of tea-stained reports. “Wednesday, obviously. It was Monday yesterday.”

“No, it wasn’t. Yesterday was Monday.”

Hargle Ploon wandered in, looking confused. “I thought it was still Sunday.”

The ship’s voice cut in: “Correction: There is currently no Tuesday in circulation. Please contact your local Bureau representative for replacement days.”

Gerry frowned. “We’ve lost Tuesday?”

“Yes,” said the ship cheerfully. “Would you like to file a complaint?”

Zorb groaned. “Not again.”

They landed in Ballykillduff to find the villagers equally baffled.

The pub calendar skipped directly from Monday to Wednesday, and the patrons were growing restless.

“I swear I was halfway through a pint when it vanished!” shouted one man.

“Mine too!” said another. “It was the best pint of the week, and now it’s gone!”

The bartender sighed. “Nobody panic. I’ve opened a missing day report.”

A small crowd murmured anxiously. Someone produced a pitchfork, just in case time needed a good prodding.

“Here we are,” he muttered. “Lost days, misplaced moons, accidental Tuesdays… ah, yes. ‘If time appears to be missing, locate the nearest Chrono-Administrative Office and demand an apology.’ Simple enough.”

“Where’s the nearest one?” asked Gerry.

Zorb checked the map. “According to this, it’s about twelve thousand light years west of Mullingar.”

Hargle looked doubtful. “Do they take walk-ins?”

They soon arrived at what looked like a giant calendar floating in space. Each month was carved into glowing marble, and the days drifted lazily around like bubbles.

At its centre sat a colossal building shaped like a wristwatch. A sign over the door read:

Inside, rows of tired clerks worked at desks shaped like hourglasses. Some were counting minutes into jars. Others were sweeping up leftover seconds with cosmic brooms.

A receptionist looked up as they approached.

“Welcome,” she said in a voice that ticked faintly. “Do you have an appointment?”

“No,” said Zorb. “But we’ve lost a Tuesday.”

The receptionist sighed. “Join the queue.”

The queue stretched into eternity. Literally. They could see it curve around several galaxies.

“We’ll be here forever,” said Gerry.

“Not forever,” said Zorb. “Just until next Wednesday.”

After several subjective centuries, they reached the counter.

The clerk behind it was a frazzled humanoid wearing a waistcoat made entirely of calendar pages.

“Lost day?” he asked wearily.

“Yes,” said Zorb. “Tuesday.”

The clerk leafed through a filing cabinet that emitted faint screams. “Let’s see… Monday’s fine, Wednesday’s accounted for… ah. Tuesday’s been reassigned.”

“Yes. Temporarily leased to a parallel dimension for administrative testing. Happens all the time. The paperwork’s still processing.”

Gerry leaned forward. “Can we get it back?”

“Possibly,” said the clerk. “If you can find who’s got it.”

They followed the coordinates to a peculiar pocket of reality shaped like a half-inflated balloon.

The day looked exhausted. It sat slumped at a desk, covered in post-it notes.

Gerry approached carefully. “Excuse me, are you… Tuesday?”

The day looked up. Its voice was slow and weary. “Used to be.”

“We need you back,” said Zorb. “Earth’s getting cranky without you.”

“I’d love to,” said Tuesday, “but they won’t let me go until I’ve completed my productivity quota.”

“Apparently I’m supposed to accomplish more in twenty-four hours than the entire rest of the week combined.”

Hargle frowned. “That sounds impossible.”

Tuesday sighed. “Tell that to the Department of Cosmic Efficiency.”

Sure enough, a door opened and a glowing supervisor drifted in, surrounded by clipboards.

“What are you doing?” the supervisor snapped. “That day isn’t authorised for release!”

Zorb stepped forward. “We’re here to reclaim it. On behalf of temporal continuity and tea breaks everywhere.”

The supervisor glared. “You can’t just take a weekday. There’s a process!”

“Fine,” said Zorb, pulling out his notepad. “Form 88-B, subsection 3—Emergency Retrieval of Temporally Misappropriated Intervals.”

The supervisor blinked. “You know the forms?”

“Better,” said Zorb. “I wrote them.”

A fierce debate followed, involving twelve regulations, three paradoxes, and one sentient hourglass that kept interrupting to recite poetry.

Eventually, the supervisor relented. “Fine! Take your miserable Tuesday. But don’t come crying to me when time starts double-booking itself again!”

Zorb nodded. “Wouldn’t dream of it.”

Tuesday stood, stretched, and smiled faintly. “Thank you. I’ll try to be punctual this time.”

“Do,” said Zorb. “We’ve had enough of Mondays pretending to be you.”

Back on Earth, the day slipped neatly back into place between Monday and Wednesday. Birds sang. Clocks synchronised. Pubs reopened.

The villagers of Ballykillduff gathered to celebrate, declaring it “The Most Productive Tuesday Ever.”

Zorb raised a cup of tea. “Well,” he said, “we’ve restored time, rescued existence, and irritated bureaucracy again.”

Gerry grinned. “All in a day’s work.”

For most of its history, the universe has been a very serious place — galaxies spinning solemnly, planets orbiting dutifully, and time marching forward like a punctual librarian. But every so often, something happens that reminds existence it doesn’t have to be so responsible.

This was one of those times.

It began with a carnival whistle.

Zorb looked up from his tea. “That,” he said, “is not supposed to happen before breakfast.”

Gerry squinted out the window. “Is it raining… gears?”

“Yes,” said Zorb grimly. “Brass ones. Which can only mean one thing.”

Hargle, who was attempting to toast a biscuit using the ship’s console, asked, “What thing?”

“The Clockwork Carnival,” said Zorb. “Temporal smugglers. They steal hours and sell them back as fun.”

They descended through the clouds and saw it: a sprawling festival stretching across the Irish countryside, its tents shimmering with time itself. Ferris wheels spun backward, rollercoasters looped through centuries, and the popcorn machines emitted faint existential dread.

Gerry stared. “I thought you said time was fixed.”

“It was,” said Zorb. “Until someone decided to throw a party in it.”

“Step right up!” he called. “Guess your century correctly and win five minutes of pure nostalgia!”

“No, thank you,” said Zorb, dragging Gerry past. “That’s how they trap you. The nostalgia’s addictive.”

They passed a carousel where the horses were clocks, galloping counterclockwise. Children (and at least one disoriented adult) giggled as they grew younger with each revolution.

Hargle stared at his own hands. “I think I just remembered something I haven’t forgotten yet.”

“That’s normal here,” said Zorb. “Mostly harmless.”

At the carnival’s centre stood a colossal tent made entirely of ticking cogs and luminous glass. At its entrance was a sign:

Inside, hundreds of beings from every corner of the galaxy crowded the aisles. Bidders held up watches, hourglasses, and—on one table—a jar labelled “Last Thursday.”

An auctioneer in a glittering waistcoat banged a gavel. “Lot seventeen! One millennium, slightly used, still under warranty!”

“Who runs this place?” asked Gerry.

Zorb grimaced. “A trickster named Ticktock Tom. Half man, half pocket watch, all nuisance.”

Sure enough, there he was on the main stage, gleaming like polished brass, his grin wide and shiny. His left eye was a clock face that ticked when he spoke.

“Welcome, one and all, to the finest moments money can buy!” Tom shouted. “Why settle for ordinary time when you can have deluxe time? Slower mornings! Longer weekends! Extended naps!”

The crowd roared with approval.

Zorb muttered, “Typical. Selling what isn’t his to sell.”

Gerry frowned. “What’s the harm?”

“The harm,” said Zorb, “is that he’s borrowing time from other universes. Eventually, someone runs out.”

Tom spotted them in the crowd. “Ah! A familiar face—or two, or three, depending on what hour it is! Zorb Blenkinsop, my old rival in reckless temporal adjustment! Welcome back!”

“I’m not here to buy,” said Zorb sharply. “I’m here to stop you.”

Tom laughed, gears whirring inside his chest. “Stop me? Oh, Zorb, the Bureau already tried that. I sold them their own lunch break!”

The audience chuckled.

Zorb stepped forward. “You’re destabilising reality. Again.”

Tom waved a hand. “Reality’s overrated. It’s much more profitable in instalments.”

He raised a glowing stopwatch. “Care for a demonstration?”

With a click, time fractured.

The world shimmered like glass. The audience froze mid-laugh. The popcorn stopped in mid-air.

Only Gerry, Zorb, Hargle, and Tom were still moving.

Tom grinned. “Lovely, isn’t it? I call it the Pause Effect. Perfect for catching your breath… or your enemies.”

Zorb glared. “You’re tampering with the clockwork of the cosmos!”

“Of course,” said Tom. “Someone has to keep it interesting.”

Gerry looked around at the frozen carnival. “Can you undo this?”

“Possibly,” said Zorb. “But I’ll need a distraction.”

Hargle raised his hand. “I’m good at those.”

He marched up to Tom and said brightly, “Excuse me, have you seen Tuesday? We lost it earlier.”

Tom blinked. “Tuesday? Oh yes, I lent it to a circus on Alpha Centauri. They needed an extra rehearsal day.”

“Ah,” said Hargle. “Good to know.”

While Tom was busy explaining the finer details of temporal leasing, Zorb reached into his coat and pulled out a small silver key.

He inserted it into the air and turned.

The world snapped back into motion.

The audience gasped, the popcorn fell, and the rollercoasters resumed their improbable loops.

Tom’s grin faltered. “What did you do?”

“Reset your clock,” said Zorb. “You’ve just been set back to standard reality.”

Tom scowled. “You can’t keep time locked forever, Blenkinsop. It’s like jelly—it wriggles.”

He pressed a button on his chest, and in an instant, he vanished, leaving behind nothing but a faint ticking sound and the smell of candied thunder.

The carnival began to fade, folding into mist.

Gerry looked around as the tents and lights dissolved into the sky. “Where’s it going?”

“Back to the cracks between seconds,” said Zorb. “Where it belongs.”

Hargle sighed. “I didn’t even get to try the candyfloss of eternity.”

“Be glad,” said Zorb. “It never stops dissolving.”

When the last shimmer of light faded, they found themselves once again on solid ground, the green fields of Ballykillduff rolling gently around them.

Gerry smiled faintly. “Peace and quiet at last.”

Zorb raised a finger. “For now. But when time goes missing once, it tends to wander again.”

The ship’s voice chimed softly. “Incoming message from the Bureau of Temporal Accounting.”

Zorb groaned. “What now?”

Gerry sighed. “Well, that seems fair.”

They laughed, even as the faint echo of Ticktock Tom’s laughter rippled across the clouds.