The Door Under the Capstone

The Door Under the Capstone

The Haroldstown Dolmen looks like a table big enough for a giant’s picnic: two portals and nine uprights, a capstone that sails like a stone ship, and wind forever threading the fields around it. School tours come, and tourists with sensible boots, and the odd poet who pretends not to shiver when the clouds stoop low. But the locals—well, the locals nod to it the way you nod to an elder who might be asleep or might be listening.

Aoife Kavanagh grew up with the stones at the edge of her days. As a child, she and her cousin Fionn dared each other to crawl under the capstone to “the other side,” which meant nothing in particular, only that you’d come out dirtier and braver. Then the years did their usual trick: Fionn went off to New Zealand to shear sheep and find himself, and Aoife studied folklore in Dublin and returned with a notebook fat with other people’s stories.

She wanted one of her own.

On a Tuesday that began with a broken kettle and the sort of drizzle that makes umbrellas feel philosophical, Aoife found an envelope addressed to her in a hand like briars. No stamp. No return address. Inside: a single sheet with words pressed in hard enough to dent the page.

Come at moonrise. Bring something lost.

Leave before the rooks call thrice.

—H

“H,” she said aloud, like that might jog the alphabet into telling her more. Her cat, Mrs Doyle, blinked in unhelpful solidarity.

Moonrise that evening was late enough that common sense could make a good case for bed, but Aoife wrapped herself in her father’s old fisherman’s jumper, tucked her notebook into her satchel, and fished a lost thing from the drawer where she kept receipts and keys for locks that no longer existed: a single domino tile, the double six, found on the road the summer Fionn left. She had picked it up because it felt like a sign. If so, it had never been clear of what.

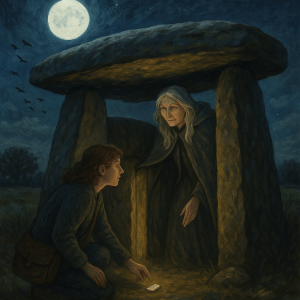

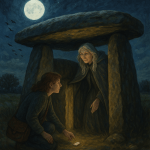

The fields around Haroldstown were a sullen quilt, hedgerows hemming them in. The dolmen hunched against the sky as if listening for distant thunder. Aoife approached with the careful casualness of someone trying not to sneak. The moon climbed the hedges and sat itself upon the capstone like an indifferent coin.

“Right,” Aoife said. “I’m here.” She felt ridiculous and brave, which is the exact mood doors prefer.

The letter had said: bring something lost. She set the domino on the earth beneath the capstone. The stones breathed—a soft shift in the temperature, a smell like old books and rain in hollows, the hairs along her forearms standing up to see better. She nearly laughed. “If this is a wind-up, it’s a good one.”

Then she saw the thin seam of darkness along the underside of the capstone flicker, as if someone had drawn a curtain back from the night. The seam widened. It was not an opening. It was the idea of an opening, which is far more dangerous. Aoife swallowed. “Hello?”

The darkness answered by showing her a shape: a woman in a coat that looked woven from fog and ash leaves. She crouched where the earth gave way to the seam, like a cat judging a lap. Her hair was not white but something that white looks up to when it wants to be dignified.

“You’re late,” the woman said, though Aoife was not.

“Are you H?”

“The letter didn’t sign itself.” The woman’s voice had the practical kindness of a midwife and the impatience of someone who has seen too many people stand gawping at miracles.

“I brought something lost.” Aoife nudged the domino.

The woman took it, weighed it as if it might yet tip the world. “Double six. Hard to lose what wants to be found. Good.” She slid it into a pocket that Aoife could not see. “Do you want to ask it?”

Aoife knew what the folklore said: don’t thank, don’t eat, don’t promise, don’t ask your real question first. Still. “Is the Haroldstown Dolmen a portal to another world?”

“Everything is a portal if you lean on it with enough hope,” the woman said. “But this—” she tapped the capstone with her knuckles, and the sound had depth it should not have had— “is an agreed place. On our side we call it the Between-Table. There are others. Some lie, some sleep, some only open when foxes sing. This one keeps a good rhythm.”

“Our side,” Aoife said, very carefully. “Your side?”

“You’ll see.” The woman held out an arm, slim as a hawthorn branch. “Mind your head.”

Aoife ducked under the capstone, and the seam widened to meet her. She did not fall. She tilted, the way you tilt in a dream just before you decide to fly. There was a smell like gorse in bloom, the taste of iron, and the faint sound of coins spun on a windowsill. Then she stood on a shore of mauve sand beneath a sky the colour of a bruise thinking about forgiving.

The dolmen stood behind her, a mirror of the one at home but not the same: its capstone was carved with spirals that resembled maps of places that might exist if you believed in them hard enough. The woman’s coat darkened until it was night itself threaded with thin silver.

“Welcome to the Else,” said the woman. “Don’t lick anything.”

“I wasn’t—”

“You were thinking about it. People always are.”

They walked. The air felt heavier here, like a blanket that had remembered it was also a sky. A line of standing stones rose ahead, each tied with a different ribbon of breath. Aoife could see the breath—thin coils, blue or gold or green, not quite smoke and not quite song. The nearest stone hummed gently.

“What are these?” Aoife whispered, as one does in a church or a library or a field at night where you’ve just met your first not-quite-person.

“Promises,” said the woman. “Left by those who wanted something and agreed to something else. The Else runs on courtesy and memory. We keep the ledgers even if the mortals forget.”

Aoife reached for her notebook. “I study—”

“I know what you study. That’s why I wrote.” The woman smiled, and it was like the moon deciding to be a person. “Stories are ledgers too. Your kind have been writing our accounts for ages. Some of you balance the books.”

“Is this where the Fair Folk live?” Aoife asked, then wished she had not said the phrase that sounded so sweet it might rot your teeth.

The woman’s mouth tilted. “Folk, yes. Fair has many meanings. So does folk. We’re not a single village, child. We’re rain and peculiar winds and the way cats look at empty chairs. I am called Haw. I serve the Between-Table. I open it when opening makes sense.”

“Why now?”

Haw glanced at the ribbons. “Because a certain boy is late coming home and the rooks have started practising wake-songs.”

“Fionn?” It leapt out of Aoife before she could stop it, as if her cousin’s name had been riding on the inside of her teeth.

Haw winced. “You mortals and your names out loud. Yes, him.”

“He’s in New Zealand.”

“That is a flavour of elsewhere,” Haw allowed, “but not the Else. He came through another door by accident and then on purpose, and you know how it is with lads—someone offers them a contest, they grow antlers. He’s played long at a game he doesn’t understand. The forfeit for losing here is to continue playing. I wrote to you because you are careful with words.”

“Careful?” Aoife thought of the letter burned into its page and the seam that had opened like a held breath released. “You barely know me.”

“I know enough. Come.”

They crossed the mauve beach into a grove where the trees grew with their roots in the air and their leaves underground. Things moved in the soil in shapes that suggested whales or the memories of whales. Light dripped from nowhere in particular. Aoife saw a child made of nettles run giggling behind a fallen trunk, leaving a smell of summer knees stung raw and soothed with dock leaves.

“Where do doors come out?” Aoife asked. “I mean—is there a map?”

Haw pointed straight up. The sky parted into panes, like a skylight in a long corridor. Through the nearest pane Aoife glimpsed a kitchen where a woman rolled out pastry with such concentration that the room itself leaned to watch. Another pane showed an empty bandstand at night, the lingering sound of a brass note taking its glorious time to fade. A third held a cliff and a lighthouse and a man scribbling a letter he would never send.

“Doors come out where the Else is almost already,” Haw said. “We are not somewhere else so much as the part of everywhere that refuses to be sensible. Your dolmen is a mouth that remembers its language.”

“What’s the price for… all this?” Aoife asked.

“The same as always,” said Haw. “Attention. Kindness. A small piece of what you do not want and therefore most need to give up. A double six domino will do for beginnings. For endings—well. We’ll see.”

They came at last to a clearing where a table stood under a roof of nothing. The table was set with a deck of cards and a ring of keys and a single white feather that looked smug. The person waiting there was Fionn, or a shape very like him, except his irises were the slick blue of a starling’s throat and he wore a crown of bracken he had no business wearing. He grinned at Aoife, and for a moment he was exactly himself, the boy who had eaten an entire jar of quince jam on a bet and been sick in the very dignified flower bed of Mrs Mulqueen.

“Aoife! Jaysus, it took you long enough. Look—” He held up a card: the ace of hearts. Then his grin scraped sideways into something brittle. “One more hand, Haw. You can’t say fairer.”

“Fairer is not the point,” Haw said. “Balance is. The rooks have cleared their throats twice.”

“I’m winning,” Fionn said. “Nearly.” He looked at Aoife. “It’s brilliant, you wouldn’t believe—every time I think I’ve lost, the game changes and I might win again.”

“That’s how not-winning works,” Aoife said, softly.

“You can take his chair,” Haw told Aoife. “If you sit, you’ll play. If you win, you both go home. If you lose, you both play again until one of you remembers what the ace of hearts is for.”

“Love,” said Aoife, too quickly.

“Maybe,” said Haw. “Also courage. Also a muscle that cramps if you don’t stretch it. Also a keyhole. The Else is not a dictionary. The Else is a kitchen drawer full of useful nonsense. Choose.”

Fionn leaned forward. “Don’t,” he whispered, so quiet she felt it more than heard it. “Do. I mean—ah, Aoife, I’m sorry. I thought I was brave. I thought I’d bring back a story and a pocketful of clever.”

“You did,” Aoife said. “You brought back yourself, only you forgot where ‘back’ was.” She looked at the chair. It had three legs and an attitude. “What happens if I don’t sit?”

“Then you walk home alone with a story and a pocketful of clever,” said Haw. “And we play on.”

The rooks called once, somewhere not far and not near. Aoife thought of the dolmen standing in its tidy field, of the hedges and the drizzle, of Mrs Doyle’s judgemental face when breakfast was late. She thought of Fionn’s mam, who kept his room exactly as he left it because she hadn’t decided yet whether it would be a shrine or a scolding when he walked back in.

“What do I owe?” Aoife asked Haw.

“For crossing?” Haw patted the pocket where the domino had gone. “Paid. For daring to ask? The bill arrives later, like all good bills. Sit if you sit. Stand if you stand. But if you sit, play like someone who knows the difference between winning and ending.”

Aoife sat. The chair sighed but held. Haw dealt. The cards were not all cards. Some were photographs that made your throat tight. Some were receipts for things you didn’t know you’d paid for. Some were leaves that had been letters in another life. Aoife took what was given and arranged it as if arrangement were a spell.

Fionn played like a man throwing pebbles at the moon because you never know. Aoife played like a woman making tea for bad news, which is to say with precision and mercy. The feather preened itself and refused to be helpful.

At the fourth hand, Aoife saw it. The ace of hearts had a flaw: a line through the middle so fine only someone who had pressed her face to the glass of life would notice. A hinge.

“A keyhole,” she whispered.

Haw’s eyebrows conducted a very small orchestra. “Do you have a key?”

Aoife reached into her satchel. Her fingers found the edges of her notebook, the stub of a pencil, the folded map of the county with a coffee stain like an archipelago. And then—cold against her palm—the missing half of the domino, not the double six but the blank end she’d lost the day she found the tile. She hadn’t known she still had it.

“Everything you lose tries to find its way home,” Haw said, as if the thought had wandered past and she’d simply pointed it out. “Even your own nerve.”

Aoife set the blank against the hinge. The ace of hearts opened. Not much. Just enough to reveal that underneath the heart was not nothing, but a small square of mirror.

Fionn leaned in and saw himself. Not crowned. Not brilliant. Just a man who had left without warning and would need to learn to arrive with it. He swallowed. The bracken crown slid off and decided to be compost.

“Do you fold?” Haw asked, gently.

Fionn nodded. “I’m tired of nearly.” He nudged his cards toward Aoife. “Win for us.”

“I don’t know how to win here,” Aoife said. “I only know how to finish what I start.”

“That will do,” said Haw. “Endings are doors the right way round.”

The rooks called twice. Time, which had been content to lounge about like a cat in a sunbeam, stood up and stretched.

Aoife put the ace of hearts face down and laid her last card on top of it, which was not a card but a bus ticket from years ago, from a day she’d gone to the sea to decide she would leave and hadn’t. She felt the weight of the decision as if it had been a small animal she’d been carrying in her coat, asleep and warm and heavier than its size would suggest. She slid the ticket across the table to Haw.

“A fare,” she said, “for two.”

Haw’s smile was the clean kind. “Paid.”

The Else let go like a breath you didn’t know you were holding. The clearing closed its eyes. The skylight panes went dark. The chair gave Aoife a dignified bruise. She and Fionn stood under the capstone in Haroldstown with the kind of suddenness that makes you ask who turned the volume down on the world.

Dawn had not committed yet; it hovered in the hedges, taking the measure of the day. The rooks called a third time. A shape—fox or luck—slipped through the grass. Aoife reached for Fionn’s hand, found it, held on like a person crossing a road with someone who doesn’t look both ways.

“Did we—?” Fionn began.

“We ended,” Aoife said. She checked her satchel. The notebook. The pencil. The map. The domino tile, whole, both ends married. She put it in her pocket. “We can begin now.”

They walked home along the lane with the politeness of people leaving a relatives’ house where they’d seen a family secret and agreed to close the curtains rather than the door. Mrs Doyle met them at the gate with a lecture about breakfast and abandonment. Fionn’s mam wept into the batter and made pancakes that tasted like reprieve.

Later, when the sun put a decent face on, Aoife returned to Haroldstown with her notebook and wrote down everything she remembered, and everything she didn’t but could feel with the edge of her mind. She avoided names and never wrote “Fair Folk,” not once. She referred to Haw as “the keeper of the seam” and to the Else as “the part of here that takes no nonsense and tolerates all wonder.” She drew the ace of hearts with its hinge and pressed a feather into the page, though not the white one, because that feather is very busy.

As for the question people ask, the one in guidebooks and late-night conversations and in letters written with briar-hands: Is the Haroldstown Dolmen a portal to another world?

Here is Aoife’s answer, scribbled in the margin where truth is happiest:

Yes. But only if you bring what you’ve lost, and only if you’re prepared to go home with less nonsense and more wonder than you came with. And only if you leave before the rooks call thrice.

Below that, smaller:

Also: do not lick anything.