A Christmas Carol, Part Two: Marley’s Redemption

A Christmas Carol, Part Two: Marley’s Redemption

Prologue – Chains in the Night

Marley’s Redemption Song #1

London—vast, smoky, shivering London—lay that Christmas Eve beneath a quilt of fog so thick and close you might have stitched it with a darning-needle and still not found the seam. The river went by like a thief in grey; bridges loomed and vanished; street-lamps stood at attention, each a little island of meek gold in a sea of pewter. The town smelt of many confident things: hot chestnuts cracking in their shells, damp wool steaming in doorways, goose-fat sighing from ovens, the iron breath of horses, and, beneath all, that sober perfume of coal which London wears as other cities wear a flower.

There was noise, too—of course there was. Bells conversed from steeple to steeple; coach-wheels fussed upon the slick stones; costermongers bawled oranges as if they had invented the very sun; children in old boots skated upon imaginary ice, drawing their letters in the frost with heels that had long since forgotten what leather felt like; and wherever the fog allowed, you might see windows writing poems of light on the mist.

Over this busy manuscript, invisible to every eye that blinked through spectacles or squinted from under caps, drifted Jacob Marley—once a partner in the firm of Scrooge and Marley, once a devotee of ledgers and locks, now a poor ghost who had counted profit so faithfully that he must count misery for a while in turn. He moved as sorrow moves—without hurry, yet always in time to find the saddest thing.

About him, as a miser wears his keys, hung the chain he had forged in life; and do not suppose it a slight thing. It clanked with iron boxes, bit with padlocks, winked with ledger clasps, and rattled with keys which had never opened anything worth opening. If guilt can be measured, this chain was a yard-stick of years; and if punishment has music, it was a concert for which no man would volunteer an encore.

Marley had been abroad since the grave took him, and had learned the geography of regret. He had trudged across roofs glazed with frost and through garrets where poets warmed their hands at the fires of their own imaginations; he had dropped into cellars where families ate hope with their bread; he had looked into counting-houses rich as puddings and found within them a hollowness that rang when struck. He had come to know the language of sighs in different districts. Southwark sighed heavily, as one who must finish his work before he eats; Holborn sighed carefully, lest anyone notice; Mayfair sighed privately behind curtains, and the East End sighed in crowds, because crowds were warmer.

On this night—this very night!—his wandering took him down a narrow lane where the fog made corners, and there, with the windows whittled to slits of fire, he paused before a house that had been indifferent to him in life and had grown precious in death. For within sat Ebenezer Scrooge, once his partner and counterpart, now a man rearranged as thoroughly as a shop in the January sales. The room, seen through the mist-glazed panes, was all brightness and bustle. There were the Cratchits, those excellent people, as snug as thrift and kindness could make them, with Tiny Tim propped in honour in a chair too big for him and yet not big enough for his cheerfulness. There was Scrooge himself, who had once kept his smile in a locked drawer; and there—remarkable sight!—was that smile freed, employed, and drawing interest every minute he wore it.

The kettle sang upon the hob with so homely a note that even the fog cleared its throat to listen; the pudding, tied in its muslin, gave a Christmas cough to announce its readiness; the goose, respectable bird, lay upon a dish in such a condition of brownness that the mere sight of it might have converted a vegetarian. They toasted, they laughed, they made a parliament of affection about the fire. Bob Cratchit, whose collar knew more starch on Sundays than it did wages on Saturdays, told a merry tale of the office coal-scuttle; his dear wife retorted with a better; and Scrooge, good soul, clapped his hands and declared each the cleverest thing since the angels had discovered carols.

Marley, poor spirit, hearing and not being heard, seeing and not being seen, felt envy—oh, shameful companion for a ghost!—rise like cold water in a flooded cellar. He pressed his hands (which were not hands) to his face (which was hardly a face), and the chain gave such a plaintive cry that the fog, which had grown used to all manner of sounds, paused a moment to pity it.

“Ebenezer,” Marley said, and his voice went through the glass like wind through the draughtiest house in Clerkenwell, “how warm you are, and how cold I am! How light your evening, and how heavy mine. It was with my terror they cowed you; it was at my warning you turned; and yet—” He broke off, not daring to finish the sum he had begun. “Oh, if there be any mercy under this sky—any coin of compassion—let it be spent on me! Give me but one chance to pay a debt honestly earned by repentance.”

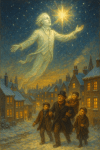

He lifted his eyes from the window and looked—where do the desperate look?—upward. It is a courageous thing to do, for heaven, even when close, seems far. The fog above had a seam, as if some finger had written on it: Open. A thin round light showed itself—as modest as the moon behind a veil, as confident as a candle in a poor man’s Christmas. It widened, it warmed, it came nearer, and Marley, all iron and ache, felt in it a tenderness he had not encountered since childhood, when tenderness is so cheap it is given away daily.

Out of that soft brightness stepped a figure that wore no terror on its brow, no merriment either, but something older than both—a patience that did not tire, and a kindness that did not boast. The figure bore in its hand a little lamp, plain as an old teapot, with a flame that held its shape as a good intention holds its course. The light from it did not shout down the dark; it conversed with it, and the dark grew reasonable.

“Jacob Marley,” said the figure, and spoke his name so simply that the worst of his pride dropped off like a rusty buckle. “You have asked, and you shall have. Not a change of past—for who can unbake yesterday’s loaf?—but a change of burden. You forged a chain; you shall unforge it. You did harm; you shall go where the harm abides and do it good. With every kindness done, a link will fall; with every mercy mended, a padlock will forget its purpose.”

“Sir—Madam—Spirit,” stammered Marley (for it had the air of all these, and the need of none), “I have no purse, no hand to grip another’s, no tongue that mortal ears will hear. How shall I do good, being unsubstantial as a rumour?”

The figure held out the lamp. “Take this.”

Marley reached and took; and wonder of wonders!—the thing had weight, a delightful, homely weight, such as a loaf carried home on a Saturday evening might have. The handle was warm; the brass remembered being polished; the flame made no sound but the small agreeable whisper of usefulness. As Marley held it, the iron all about him creaked as though surprised.

“Where shall I go?” he asked humbly.

“Begin,” said the Spirit, “where you began to be unkind. Men do not slip at the cliff first; they stumble at the threshold. The lamp knows the way.”

And truly, even as it was said, the flame leaned in his hand, as a flower leans toward the sun. It pointed through the fog not with a straight command but with a gentle invitation. Marley, who in life had never followed anything that did not promise coin, now followed a light that promised labour. He moved from the window—one last look he could not help but throw, and in it saw Scrooge take Tiny Tim upon his knee—and away he drifted into the older, poorer lanes, where the fog served as a blanket for families that could not afford another.

As he went, the world of London broadened beneath him like a map unrolled. He floated over a rag-seller’s shop where a woman bargained for a shawl with pennies won from washing; past a coffee-stall where men in paper collars warmed their hands around cups, and the steam made saints of them briefly; by a church whose choir-boys, having sung all afternoon, were eating their suppers with a severity of appetite that allowed no hymn but chewing. He passed spirits too, of his own lamentable fellowship—wretches laden with the hardware of their crimes, reaching out spectral hands to help and passing through what they longed to succour. They groaned, seeing him with a lamp where they had none; and Marley, newly junior in the company of the damned-no-longer, bowed to them with a humility strange upon a man who had once refused a clerk a candle after dusk.

The lamp’s flame bent sharply at a corner like a dog catching a scent. Marley followed into a court so narrow that two cats could scarcely pass in conversation. Here a door stood which he knew—oh, perfidy of memory!—as a creditor knows the door that will open to his knock. He had crossed this threshold once with paper in his breast-pocket and winter in his heart. He had spoken to a woman then whose husband lay newly cold in the shop he could not keep. He had explained, with all the politeness that makes cruelty correct, that foreclosure was not a matter of feeling but of figures; and figures are famously deaf.

The door lifted at his approach—not by latch or hinge, but by consent of the lamp—and Marley passed within. The room was tidy with poverty: a chair mended frankly with twine, a table that made no parade of its wobble, a hearth with only the ghost of a fire, which is a common ghost in London. At this table two women sat—a mother with lines smoothed by patience rather than by comfort, and a daughter whose youth did what it could with too little; for youth is generous and will spend itself. They stitched by candle-end, not with the sharp administrations of a professional needle but the faithful jabbing of necessity.

“Here,” said the lamp—not in words, but in a certainty that ran along Marley’s arm—“here is the threshold where you stumbled.”

He would have fallen on his knees, but ghosts have poor knees and furniture does not always respect them. “What can I do?” he cried softly. “I cannot fill the pot, nor plump the pillow, nor add sugar to the tea. Must I only watch—and remember?”

The lamp made answer by action. Its light laid itself upon a shelf where papers lay tied up with string the string had outlived. Ledgers—how well he recognised the breed!—and receipts with figures so hard they looked as if they had been carved rather than written. The light entered the ink; the ink loosened; the figures hesitated; and what had been written in the grammar of debt began, without noise or drama, to conjugate itself in the tongue of mercy. A receipt forgot to demand; a note remembered to forgive; and across a cruel column that had once totted up a future paid in tears there crept, letter by letter, a word that is the very cousin of Christmas: Settled.

Marley watched with a wonder that did not diminish. Something shifted at his breast: a tug, a click, a slackening; and one link—the smallest, perhaps, but the first—is always the sweetest—dropped from his chain and fell upon the floor without sound, as if humility makes even iron polite.

The mother started, laid down her needle, and pressed her hand to her heart. “Child,” she whispered, “did you—hear anything?”

“Only the kettle thinking about boiling, Mother,” said the girl with a brave smile.

“Strange,” murmured the mother. “For I felt as one feels when a heavy cart that has stood all day at the door is at last rolled away.”

Marley, overcome, raised the lamp higher, and the little room warmed—not in degrees, perhaps, but in temper. The faces before him, still pale with want, grew rich with something that want cannot vanquish. He found himself speaking, though they could not hear: “Forgive me. Forgive me that I measured you in columns when you are worth chapters.”

The lamp inclined again, businesslike in its pity. “There is more,” it seemed to say. “A chain is not cut by one snip.”

“Lead on,” said Marley, with a humility that would have shocked his own portrait. He took a last look at the women, as a man looks back at a house he has left in better order than he found it, and moved out into the court. The fog met him as old colleagues meet: suspiciously first, then admitting that perhaps there is something to be said for reform.

So began Jacob Marley’s second apprenticeship. He who had served figures learned at last to serve people; he who had counted coins prepared to count blessings; he who had boasted of being exact proposed to be generous with the same exactness. The lamp went on before, a patient star at doorstep height, and Marley followed where it led, clanking still but lighter for the hope that had crept between the links.

London stretched ahead like a ledger yet to be balanced. Marley, with the lamp for pen and pity for ink, set himself to it.

Chapter One – The Petition Granted

Marley’s Redemption Song #2

Chapter Two – The Widow and the Debt

Marley’s Redemption Song #3

Morning in London is no gentle suitor. It rattles the shutters, barks through the mouths of costermongers, shakes children out of sleep with a clamour of milk-carts and muffin-bells, and leaves the fog to mop up what it cannot be bothered to disperse. That Christmas-tide dawn was no exception. The city was a symphony of stirrings—horses stamping and steaming, fishwives raising their cries till the very haddock blushed, the clink of spoons against teacups in houses fortunate enough to possess either tea or cup.

In the narrow lodging where Mrs. Wentworth and her daughter had endured the night, the old air of want was yet on the boards, but something warmer—some unseen benediction—hovered there also. The lamp Marley carried still glowed faintly, though it was invisible to mortal eyes. It had performed its work silently, rewriting cruel figures into merciful ones, and now it seemed content to watch its consequences unfold.

A sharp knock came at the door. Not the impatient tattoo of a dunning creditor, nor the sly tap of a neighbour with news, but a firm, official summons. The widow started, her heart tightening, while her daughter, needle poised in trembling fingers, looked to her with eyes that asked, Again? Must we endure another blow?

The knock repeated itself, civil yet insistent.

With the dignity of one who had long since learned to greet calamity upright, Mrs. Wentworth drew her shawl closer and opened the door.

There stood a young man of clerkly aspect: neat coat, ink-smudged cuffs betraying his true trade, and a face so honest it looked almost embarrassed to be delivering business. In his hand he bore a folio, tied with string that was nervous to be trusted with anything important.

“Mrs. Wentworth?” he enquired, lifting his hat.

“Yes, sir,” she said, her tone already braced for the axe.

“I come from the offices of Messrs. Scrooge and Cratchit,” he replied, and then hesitated—for he saw the flicker of dread pass over her face, and it pained him. “But do not fear, madam. I bear no threats of arrears. Quite the contrary!”

He stepped inside at her faint gesture, placed his folio upon the rickety table, and began untying the strings with fingers that trembled more from anticipation than cold. The daughter leaned forward, her lips parted in anxious curiosity.

“These papers,” the clerk said, spreading them with a solemnity suited to scripture, “contain accounts once held against you. By the new direction of Mr. Scrooge, and with the hearty assent of Mr. Cratchit, they are—” He paused, and a smile, shy but genuine, blossomed on his lips. “—they are forgiven.”

The word fell into that poor chamber like a great golden coin dropped into an empty purse.

The daughter gave a little cry, half laugh, half sob. The mother swayed, clutching the back of the patched chair.

“Forgiven?” she repeated faintly. “You are certain, sir? Forgiven?”

“As certain,” said the clerk, “as the sun’s rising this very morning. The debts are no more. The accounts are settled—settled in mercy.”

At that, Mrs. Wentworth sank into the chair, tears spilling freely down her worn cheeks. Her daughter knelt beside her, clasping her hand, repeating the blessed word like a charm: “Forgiven, Mother—do you hear? Forgiven!”

The clerk, encouraged by their joy, shuffled his papers again. “And there is more. A post is offered to your daughter in the sewing-room at Scrooge & Cratchit. The wages are honest, the work steady, the overseer kindly. If she will accept, she may begin at once.”

The girl stared, her needle still clenched between her fingers. “Mother—did you hear?” she whispered.

The mother, mastering her sobs, drew her daughter close. “Take it, child! Take it, and give thanks every day of your life for the miracle that has come to us.”

The clerk coughed, a little embarrassed at his own emotion, and added: “I myself was sent hither by an impulse I cannot explain. It woke me before dawn and would not let me be. ‘Go to the widow in Holborn,’ it urged, ‘and see the wrong made right.’ I believe—nay, I am sure—that Providence itself directed my feet.”

Above them, Marley’s ghost wept. He held the lamp to his breast, and its flame swelled with triumph. Another length of iron fell from his chains, vanishing like snow upon a fire. For the first time since death, he felt not only sorrow but a stirring of hope.

The widow, rising, took the clerk’s hand between her own. “Tell Mr. Scrooge,” she said, her voice steady though thick with tears, “that Lucy Wentworth prays for him by name this day and every day hereafter. And tell Mr. Cratchit the same. Their mercy has lifted a burden heavier than they can guess.”

The young man bowed deeply, replaced his hat, and departed, his step lightened as if he had left behind a portion of his soul in that grateful room.

When the door closed, mother and daughter fell upon each other’s necks, laughing and weeping together, repeating words of thanksgiving, and finally remembering, with almost comic haste, that breakfast must now be made to honour the miracle.

Marley, unseen, drifted through the door after the clerk, his chains lighter, his spirit steadier. The lamp tugged once more, its flame bending like a compass needle toward the alleys eastward. It pointed to Cheapside, where another soul of his making suffered want.

“On then,” Marley whispered, the words both plea and vow. “On to the next wrong. I will not falter.”

And the lamp, patient as eternity, led him on.

Chapter Three – The Clerk Forgotten

Marley’s Redemption Song #4

The lamp led him, as lamps will, not by the broad roads where carriages proclaim prosperity, but through narrower arteries of the city where misery circulates more freely. Marley drifted above alleys whose cobbles shone with frost, where the fog sat low as a landlord upon his tenants, demanding rent from every cough.

He knew these quarters. Oh yes! He had once sniffed at them disdainfully from the high seat of his chaise, considering their inhabitants as mere figures in ledgers—costs, defaults, write-offs. Now he saw them differently, for a man regards the world otherwise when every brick cries out his name as accuser.

The lamp guided him into a lane so cramped that laundry, long since stiffened into boards of ice, still hung across it like banners at a funeral. There, upon a stool whose three legs had once been four, sat a man hunched against the cold. His shoulders wore a coat reduced to apology, his knees shivered beneath breeches mended until the patches had begun to quarrel with one another. A pair of cracked spectacles, clinging gamely to his nose, lent his face a dignity undiminished by want.

Upon the cobbles he scratched sums with a stick, whispering them under his breath. His finger pointed, as though to an invisible column: “Carry the one… no, that won’t do… balance against… oh dear, oh dear.” He shook his head, rubbed out the figures with his sleeve, and began again.

Marley knew him instantly. “Fitzwilliam,” he gasped, covering his face with ghostly hands. “My faithful clerk, dismissed for a mistake no heavier than a feather, though I made it weigh as lead!”

The memory came upon him with merciless clarity. He saw again the counting-house—his own voice, harsh as a closing lock—“A thief you must be, sir, to make such an error!”—the poor man’s protest, the appeal in his eyes, the final hopeless bow as he departed, livelihood broken at a stroke. Marley had thought it nothing then, a necessary severity. Now it rose up like a monument built of his shame.

“Oh cruel tongue!” Marley moaned, and the chain about his shoulders rattled as if agreeing. “I cast him into poverty with a word sharper than any sword.”

The lamp pulsed, urging him onward. Marley held it near Fitzwilliam. The flame grew, spreading a gentle warmth that curled like breath into the old man’s frozen fingers. Fitzwilliam paused, looking up with puzzled eyes, as though some comfort had come unbidden.

But Marley could do no more. He was a shadow, unable to place coin in the poor man’s hand, unable even to lay a hand upon his shoulder. He groaned aloud. “What good is pity without power?”

At that very moment, the lamp leaned eastward. Marley, trembling, understood. He sped across the streets, through walls and windows, until he came to Scrooge’s bedchamber.

There lay Ebenezer, older now, but not in the way of decline: older as an oak grows older, putting on rings of generosity. Yet even oak must sleep, and Scrooge dozed before the dying fire, spectacles askew upon his nose, a smile lingering as if his dreams were companions.

Marley bent over him. The lamp flared, and its light fell across Scrooge’s face. The chains rattled softly, not in misery but in entreaty.

“Ebenezer,” Marley whispered, his voice like the sigh of a long-forgotten bell, “Fitzwilliam. Seek him. Restore him. Fail him not, as I did.”

In his dream, Scrooge saw Marley once more—not as the tormented wretch who had first appeared years ago, but luminous, pleading, with a lamp that burned like a star. Scrooge woke with tears upon his cheeks and a name upon his lips.

“Jacob,” he murmured. “Fitzwilliam. Yes—yes, I shall.”

And so it was that, at first light, Scrooge left his house with Bob Cratchit at his side. They searched the streets until they found the alley, and there, hunched upon his stool, was Fitzwilliam, scratching sums upon the stones.

“My dear fellow!” cried Scrooge, his voice ringing with compassion. “How could the world have forgotten you, when you once served so faithfully?”

The old clerk looked up, dazed. “Sir—Mr. Scrooge?”

“Yes, Fitzwilliam, it is I. And I tell you now, you shall not sit in frost and hunger a day longer. You shall return to the counting-house. A desk waits for you, wages honest and ample. And more than that, friendship, warmth, and the respect you always deserved.”

Fitzwilliam’s lips trembled. He removed his cracked spectacles, wiped them with a rag, and yet still could not believe the vision before him. Tears coursed down his face—tears that spoke more eloquently than speech.

Marley, watching unseen, raised the lamp high. With a great shudder, a heavy portion of his chain fell away, link after link, until the ground below rang with their vanishing. He laughed—yes, laughed!—a sound thin and strange, but laughter nonetheless.

“Oh blessed day!” he cried. “Another wound healed, another debt repaid. Heaven grant me more, that I may work until the last link is gone!”

The lamp inclined once again. Its flame pointed toward the broader streets where children played at hopscotch and shouted rhymes, their breath clouding the frosty air. Marley followed, his spirit trembling with expectation.

There, upon a stone step, sat a ragged boy whose hollow cheeks bespoke hunger, and whose eyes, sharp with need, saw everything yet were seen by no one. Marley’s ghostly heart sank.

“The Burtons’ child,” he whispered. “Grandson of the man I ruined. My sin walks abroad in his very flesh.”

The lamp burned brighter. Marley, his chains fewer but not yet gone, drifted nearer to the boy—toward his next act of restitution.

Chapter Four – The Boy on the Street

Marley’s Redemption Song #5

The lamp’s glow pulled Marley forward, its flame bending like a compass needle toward a busy thoroughfare where London’s pulse beat fastest. The fog had thinned, and a pale winter sun did its best to polish the rooftops, though the day still bore the chill of iron. Street cries clattered from every corner: “Hot chestnuts! Fresh muffins! Oranges, sweet as summer!” Carters shouted at horses, dogs barked at the carters, and somewhere a fiddler scraped out a tune as brisk as the weather.

Amidst all this bustle, humanity flowed—merchants in fur-collared coats, maidservants with baskets, urchins darting under wheels, clerks with ledgers under their arms. And there, upon a stone step half-buried in slush, sat a boy. His coat was scarcely a coat at all, more sack than garment, its threads fraying into despair. His cap, once jaunty perhaps, now hung limp with damp. His shoes had long since lost the argument with the cobblestones; his toes, blue with cold, peeked out like unwelcome guests.

He held out a hand—thin, trembling, grimy—yet few looked down. A lady stepped wide to avoid him, drawing her skirts as though pity were contagious. A butcher’s boy tossed him a word sharp as a bone, but no morsel. A banker in fine gloves passed so close that the boy might have brushed him, yet the man never saw him at all.

Marley hovered, chains dragging through the snow with a sound that only he could hear. He knew this child. The face, hollowed by hunger, bore the unmistakable look of James Burton—an honest tradesman Marley had once ruined with the foreclosure of a loan. Burton had pleaded, had promised repayment given time; but Marley, impatient for gain, had stripped him of shop and dwelling alike. The man had died in poverty. And here was his grandson, bearing the inheritance of Marley’s cruelty.

“Oh, merciless hand!” Marley cried, wringing his ghostly fingers. “I wrote his misfortune as neatly as one writes a sum, and now behold! The sum grows legs and starves in the street.”

The boy shifted, clutching his thin knees to his chest, his lips blue as the winter sky. Marley bent low, wishing with all his soul he might warm the child with his own body. But he was a shadow; his touch was air.

At that moment, the lamp flared. Its golden glow spilled across the step, and in that light came the sound of laughter—warm, familiar laughter. Bob Cratchit appeared with his brood tumbling about him like sparrows, their cheeks bright from the cold. Behind him walked Ebenezer Scrooge himself, who had taken to joining the family on their walks with the eagerness of a boy who has been given back his childhood.

Tiny Tim rode upon Bob’s shoulder, his crutch tucked jauntily beneath his arm. His face was bright with cheer, and his eyes, sharp as only a child’s can be, caught sight of the ragged boy on the step.

“Father,” he whispered, tugging at Bob’s hair. “There’s a child there—do you see? He looks colder than I ever did. Might we not—?”

Bob turned, and his kind heart, ever alert to suffering, was pricked at once. “Poor lad,” he murmured. “See how he shivers. I could scarce pass him by.”

But Scrooge had already noticed. He paused, his brow furrowing, then softening as his eyes rested upon the boy. There was recognition there—though he could not have said why. Perhaps Marley’s whisper reached him in that moment, for he heard in the air a voice faint as the rustle of a ledger’s page: This is the fruit of my cruelty. Fail him not, Ebenezer.

Scrooge knelt, his red scarf brushing the slush. “Come, my boy,” he said gently, holding out a hand. “This step is no place for Christmas. Come in with us. There is bread and broth, and a seat by the fire.”

The boy blinked, disbelieving. His thin hand trembled, then grasped Scrooge’s with desperate strength. He tried to rise, stumbled, and would have fallen, but Bob caught him, steadying him as if he were one of his own.

“Up you come, lad,” said Bob cheerfully. “We’ve a house where laughter is louder than hunger, and you’ll not be turned away from it.”

The other Cratchit children crowded round, full of innocent wonder, already debating who should sit beside him, who should share their slice of pudding. Tiny Tim, with his small face radiant, patted the boy’s arm. “You’re safe now,” he said.

Above them all, Marley floated, his hollow eyes brimming with tears that steamed away in the lamp’s glow. With a great thunder, a length of chain slipped from him—heavy, grievous, long—and fell into the snow, dissolving at once. The weight upon him lessened so suddenly that he cried out, a sound of laughter mingled with sobbing.

“Oh, bless them!” Marley exclaimed. “Bless Bob, who never fails to see the lowly. Bless Tim, who speaks with an angel’s tongue. And bless you, Ebenezer, my friend—you who repair what I destroyed.”

The boy was led away into warmth, and Marley, lighter than he had ever been, raised the lamp high. Only one chain remained—thick, black, immovable, heavier than all the rest. The lamp’s flame bent, pointing not to the bustle of the street but to a quieter quarter of the city, where snow lay hushed upon roofs and a single window glowed faintly through the frost.

Marley knew that window. His heart, such as ghosts may have, contracted with dread. For behind it lay Clara, the woman he had once loved, and cast aside for the clink of coin.

“Must I see her too?” he whispered.

The lamp flared steadily, without mercy.

Marley bowed his head, trembling. “Then lead on. For if forgiveness is to be found there, it shall be the final link undone.”

And he drifted, chains rattling their last, toward the chamber of his final trial.

Chapter Five – The Final Kindness

Marley’s Redemption Song #6

The lamp guided Marley away from the crowded streets, where laughter and commerce jostled shoulder to shoulder, into quieter lanes where the snow dared to keep its shape. Here the city was hushed, as if even London, that tireless engine, knew that some houses contain secrets too fragile for noise.

The flame bent toward a modest dwelling, its shutters warped, its door paint rubbed thin by years of weather. One window alone gave light—a single candle that had fought bravely against the dark and, though guttering, would not yet surrender.

Marley paused, his ghostly breath forming no cloud, yet heavy in his chest. He knew this place. He had passed it in life without daring to enter, though once it had been his second home. He whispered the name that trembled upon his lips:

“Clara.”

She had been the only tenderness of his youth—gentle, plain perhaps to others’ eyes, but to him radiant as spring. She had urged him to choose kindness over coin, to see people as more than accounts. And he, blinded by ambition, had set her aside with cold words and a colder silence. A man must attend to business, he had told her. And she had bowed, wounded but dignified, and stepped out of his life as softly as she had entered.

Now she lay within, her life all but spent.

The lamp flared, insisting. Marley drifted through the wall and entered.

It was a simple chamber, almost bare. A chair, its arms smoothed by faithful use, stood by the bedside. Upon the coverlet lay an old woman, her hair white as the snow upon the sill, her face marked by lines that spoke of hardship endured with grace. The Bible lay open upon the coverlet, her frail hand resting upon it as though she had turned its pages with her last strength.

Marley sank beside her, chains clattering softly, and fell to his knees.

“Clara,” he whispered, though she could not hear. “Forgive me. Forgive Jacob Marley, who loved you once and left you for ledgers. I have seen the ruin of my ways—I have wandered in chains heavier than stone—and all my labours have led me back to you. Speak the word, if it is in you, and let me be free.”

The candle guttered. Clara stirred faintly. Her lips moved, breath a thread, but the words reached Marley’s ears as though carried on the wind of heaven itself.

“I forgive you, Jacob.”

The chains shuddered. A sound filled the room, like bells breaking into chorus. One by one, the iron links burst apart, dissolving into light. Padlocks melted into nothing, boxes fell away as if they had never been. The last and heaviest coil slipped from his shoulders and vanished.

Marley staggered, clutching the lamp—but no, the lamp had vanished too. Its flame had not gone out; it had entered him. His chest glowed with its radiance, his form brightened until he shone as though he were made of starlight. The burden was gone.

He bent low, pressing a ghostly kiss upon Clara’s brow. Her lips curved in a faint smile, and with a final sigh, she closed her eyes. The candle flickered once, then went out, leaving the room in a holy stillness.

Marley rose. He was lighter than mist, brighter than the snow outside. Through the roof he drifted, up into the star-strewn sky, his chains left behind forever.

“Oh, merciful Heaven!” he cried. “I am free. I, Jacob Marley, who was bound in greed, am free.”

And as he rose higher, he looked down one last time. He saw Scrooge walking with Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim through the snowy street, the rescued boy among them, laughter trailing after like a ribbon. Scrooge paused, as though sensing something, and raised his hat to the empty air.

Marley lifted his radiant hand in blessing. “Farewell, Ebenezer. Farewell, Clara. Farewell, London. Live kindly, all of you—for kindness is the only wealth that endures.”

Then he soared upward, chains no more, lamp no more—only light.

Chapter Six – The Song of Freedom

Marley’s Redemption Song #7

The city of London lay beneath him, muffled in snow and alive with bells. From every steeple they rang, some bravely in tune, others with the honest wobble of metal long overworked; yet all together made a music that seemed, to Marley’s ears, more beautiful than any choir of kings. He drifted above rooftops powdered like plum-cakes, above alleys that smoked with the steam of Christmas dinners, above shop windows glowing like lanterns of cheer. For the first time since death claimed him, Marley felt no weight, no rattle of iron, no ache of guilt dragging him earthward.

His form glowed faintly, as though the little lamp he had borne had lodged itself in his very breast. It warmed him, it lifted him, it filled him with a joy so strange that he laughed aloud, and the laughter rang not like chains but like carols.

Below, the Cratchit family spilled from their door, Bob with his scarf flapping like a banner of contentment, Mrs. Cratchit smiling despite her perpetual concerns, the children chattering like sparrows. Tiny Tim rode high on his father’s shoulder, his small crutch tucked like a sceptre beneath his arm. Beside them walked Ebenezer Scrooge, who not long ago had been the terror of counting-houses and is now their favourite guest. His step was brisk, his eye bright, his hat tipped at every neighbour. At his other side trudged the ragged boy Marley had seen upon the step, no longer ragged, but already shining with the prospect of belonging.

Marley paused in the air, unseen above them, and stretched out his shining hands in blessing.

“Farewell, Ebenezer,” he whispered. “My friend, my better. You found redemption first, and in your finding lit the way for me. Farewell, Bob Cratchit, whose kindness shamed my cruelty. Farewell, children, who never cease to teach their elders. And farewell, London, noisy, hungry, generous London—you were the ledger I balanced too late, but at last I have written one good entry in your favour.”

The air trembled, and Marley felt himself rising higher. The fogs of the city dropped away, the bells grew distant, and the stars came nearer, bright and welcoming. They seemed to open like a great gate, swinging wide upon their hinges of eternity. From beyond them came a sound—not of chains, nor groans, but of voices. A chorus, immense and tender, filled the heavens. It was the song of spirits freed, of burdens cast down, of souls mended at last.

Marley joined it. His voice, once a groan of iron, now soared like a note of silver. It mingled with the choir until he could no longer tell his own from theirs. He was not alone; he was never to be alone again.

And if, in some midnight dream, Ebenezer Scrooge thought he heard his old partner’s laugh—lighter, merrier, and full of peace—it was no fancy. For Jacob Marley was at rest.