By the fourth week of rain, Ballykillduff stopped pretending it was temporary.

The first week had been called unfortunate. The second was concerning. By the third, people were beginning to mutter phrases like biblical and I don’t remember it ever being this wet, which in Ballykillduff was the traditional signal that something had gone deeply wrong with reality.

Jimmy McGrogan noticed it on a Tuesday.

Not the rain itself—everyone noticed that—but the way it behaved. Rain usually arrived with a bit of manners. It fell, it soaked, it left. This rain had moved in. It lingered. It leaned against doorframes. It watched through windows. It fell at angles rain had no right to fall at, drifting sideways, upwards occasionally, as though unsure which way gravity was supposed to be working that week.

Jimmy stood in his yard, rain dripping off the brim of his cap, watching the river swell until it looked less like a river and more like a decision someone had made in a panic.

“That’s not stopping,” he said aloud.

This was important, because Jimmy McGrogan was not a man given to exaggeration. When Jimmy said something wasn’t stopping, it usually meant it had already passed reasonable and was heading briskly toward legend.

By Wednesday morning, the chickens were refusing to come out of the shed, the dog was sulking under the stairs, and the postman had taken to delivering letters by throwing them vaguely in the direction of houses and hoping for the best.

That was when Jimmy began measuring.

No one noticed at first. Ballykillduff had learned long ago that noticing Jimmy McGrogan too early only made things worse. He paced the length of his field with a tape measure and a look of grim concentration. He made notes on the backs of old envelopes. He stared at the sky, nodded once, and went inside to make tea so strong it could have removed paint.

On Thursday, he bought timber.

“Doing repairs?” asked Mrs. Donnelly in the hardware shop.

“Something like that,” said Jimmy.

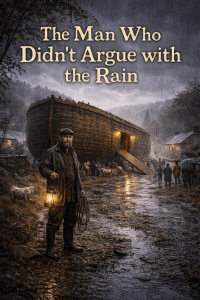

On Friday, the shape became unmistakable.

It was an arc. Not a curve, not a suggestion—an unmistakable, deliberate arc, rising from the soaked earth behind Jimmy’s house like an idea that had finally committed to itself. By Saturday afternoon, half the village was standing at the hedge, umbrellas sagging, watching him work.

“Is that…?” someone began.

“Yes,” said Jimmy, without looking up.

“But—”

“Yes.”

“Are you sure?”

Jimmy drove a nail home with unnecessary emphasis.

By Sunday, the rain intensified, as though offended.

The river spilled over its banks. The lower lane disappeared entirely, leaving only the tops of familiar signposts sticking out like accusations. A cow appeared in O’Flaherty’s yard, confused but polite. The church steps developed a small waterfall, which Father Keane insisted on blessing, just in case.

And Jimmy McGrogan kept building.

By the time the arc was finished, it was enormous—solid timber ribs, sealed seams, a roof sloping just enough to argue with the rain instead of surrendering to it. A door wide enough for decisions. A ramp thoughtfully added, “for anything with opinions,” Jimmy explained.

“What exactly do you think is going to happen?” asked Mrs. Donnelly.

Jimmy wiped his hands on his trousers and looked out across Ballykillduff, now shimmering with water and reflection.

“I don’t think,” he said. “I’ve checked.”

That night, the rain reached a pitch it had been working toward all along.

It fell with purpose. With memory.

People woke to water at their doorsteps, then in their kitchens, then tapping politely at the stairs. And when they went outside—boots sloshing, torches bobbing—they found Jimmy already there, opening the great wooden door of the arc.

He did not shout. He did not panic.

He simply nodded and stepped aside.

By morning, Ballykillduff floated.

Not dramatically—no roaring waves, no lightning—but gently, stubbornly, as though it had decided to refuse sinking out of spite. The arc rocked slightly, tethered to what remained of the higher ground, filled with people, animals, boxes of things someone couldn’t quite bear to leave behind.

And then, just as suddenly as it had begun, the rain stopped.

It did not slow. It did not apologise.

It stopped.

Water drained away with reluctant sighs. The river returned to something like itself. Mud claimed the streets. Ballykillduff reappeared, damp, bewildered, but intact.

Jimmy McGrogan dismantled the arc the following week.

Used the timber for sheds, fences, and one very fine bus stop. He never spoke much about it afterward, except once, when someone asked him how he’d known.

Jimmy thought for a moment.

“Well,” he said, “when the rain forgets to leave, it’s best to be polite—but prepared.”

And in Ballykillduff, no one ever argued with that.