The Queue: A Quiet Story of Alice

Chapter One

In Which a Queue Appears Without the Decency of an Explanation

On the second of January 2025, Ballykillduff woke with the sort of reluctance usually reserved for Mondays, dentists, and the last slice of fruitcake that will not admit it is stale.

Christmas had not so much ended as it had sulked off, leaving behind evidence. A few brave lights still blinked in hedges, as if they had not received their dismissal papers. A wreath hung sideways on the door of the post office, like a hat worn in protest. Somewhere up the lane, a plastic reindeer lay on its side in a ditch, staring at the sky with the blank patience of something that had once been festive and now wished to be left alone.

The air was clean and cold, with a thin mist that made the village seem slightly unfinished. If you looked down the main street, the houses were there, certainly, and the shopfronts were where they ought to be, but the far end faded into grey, as if Ballykillduff had been drawn with confidence at the start and then the pencil had lost interest.

Alice noticed all of this at once, because she had always been very good at noticing the unimportant parts of important things, and the important parts of unimportant things, and the parts that insisted they were neither.

She had arrived in Ballykillduff some time ago in a manner that did not bear repeating in polite company. It was enough to say that she was here now, and that the village had a way of accepting the impossible with the gentle nod of people who have seen worse. The locals did not ask where she came from any more than they asked where fog came from, or why the Giddy Goat pub’s clock always ran five minutes late on purpose.

On that morning, Alice was walking down the street with her hands in her coat pockets and her breath making pale clouds that vanished too quickly to be trusted. She had been sent on a simple errand, which is often the beginning of complicated things.

“Go up to Mrs Delaney’s,” Bridget had said, pressing a small tin into her hands, “and bring her a bit of the plum loaf before it goes too hard to be chewed.”

“Why can she not bring her own plum loaf?” Alice had asked, because she liked to see if questions would behave themselves.

“Because,” Bridget replied, “she is Mrs Delaney.”

This explained everything, and explained nothing, which is the proper amount of explanation for Ballykillduff.

So Alice walked, and as she walked she noticed something odd. It was not odd like a dragon in a bathtub, or a tea party in a tree, or a rabbit with a pocket watch. Those were the kinds of odd that made a noise about it.

This was odd in a quieter way.

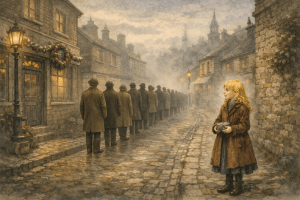

There were people standing outside O’Rourke’s Hardware.

At first, Alice thought they were only standing, which is a thing people do. But they were standing in a particular manner, facing the same direction, spaced with a careful politeness, as if any of them might at any moment say, “Sorry, were you ahead of me?” and then refuse to accept the answer.

It was, in short, a queue.

Now, Ballykillduff did queues very well. Ballykillduff could queue for the opening of a shop that had already been open for an hour. Ballykillduff could queue for the sake of queuing, and find it a pleasant way to spend a morning. Ballykillduff could queue in the rain without umbrellas as a point of principle.

But this queue had several peculiarities.

The first was that O’Rourke’s Hardware was not open.

The second was that it was far too early for anybody to want hardware.

The third was that there was no sign.

Alice slowed down and looked for one anyway. She checked the window, the door, the wall, and even the guttering, because sometimes signs are hung in unusual places when they are shy.

There was nothing. Only the dark glass of the shopfront, reflecting the pale road and the pale people and the pale sky.

The queue began at the hardware shop and wound along the street, past the bakery, past the chemist, past the small charity shop that smelled of wool and old decisions. It curved gently as if it were trying not to be a bother. It did not stop at any sensible point. It simply continued, disappearing around the corner by the old stone wall where the ivy grew in a way that suggested it had a private life.

Alice stood at the edge of the pavement and stared, because staring is what one does when one hopes the world will notice and behave better.

No one in the queue stared back. They all faced forward. Their hands were in pockets. Their shoulders were slightly raised against the cold. Their expressions were mild, as if queuing without understanding was perfectly ordinary, and perhaps even recommended.

A man near the middle of the line held a bag from the butcher’s. It was empty, but he held it carefully, as if it contained something delicate. A woman in a green scarf clutched a folded umbrella that was not open and had no intention of being open. A boy, perhaps eight or nine, stood between two adults, looking down at his shoes with the air of someone who had once had plans and had mislaid them.

Alice walked along the line, not entering it yet, only inspecting it from a safe distance, as one inspects a puddle that might be deeper than it looks.

“Excuse me,” she said to the nearest person, a woman whose cheeks were pink from the cold, “what are you all queuing for?”

The woman blinked slowly, as if Alice’s voice had reached her from a great distance.

“For the front,” the woman said.

“Yes, but what is at the front?”

“The front,” the woman repeated, and smiled politely, as if the matter was settled.

Alice tried another person, a man with a hat that looked like it had been sat on and then forgiven.

“Good morning,” Alice said. “Could you tell me what the queue is for?”

The man looked genuinely pleased to be asked, which was worrying.

“It is for going next,” he said.

“Next to what?”

He gave her the indulgent look adults give to children who have misunderstood a rule that was never explained.

“Next,” he said again, and then turned his gaze forward as if it would be rude to look away.

Alice felt, for a moment, as if she had stepped into a conversation halfway through and everyone else had the script.

She walked further down the line.

At the very beginning, by O’Rourke’s Hardware, stood an elderly woman Alice recognised as Mrs Phelan, who was the sort of woman who could make a complaint sound like a blessing.

Mrs Phelan was first. That alone made the queue suspicious, because Mrs Phelan was often first in things she had not attended.

Alice approached carefully.

“Mrs Phelan,” Alice said, “what are you waiting for?”

Mrs Phelan did not turn. Her head remained pointed toward the closed shop door, which might have been a little insulting if it had not been so determined.

“I am first,” Mrs Phelan said.

“Yes,” Alice replied, “but why?”

Mrs Phelan sighed in the manner of someone who has endured much foolishness and expects to endure more.

“Because,” she said, “if you are not first, you are behind. And if you are behind, you are only waiting twice.”

“Waiting twice for what?”

Mrs Phelan made a small sound that was not quite a laugh and not quite a cough.

“For afterwards,” she said.

Alice stared at the shop door. It was perfectly ordinary. It had a little sign that said CLOSED, which it always did when it was closed. It had paint peeling in the corners. It had a handle that had been polished by years of hands that believed in the usefulness of handles.

There was nothing on the door that said AFTERWARDS, or NEXT, or FRONT, or even QUEUE HERE.

“Who started the queue?” Alice asked.

Mrs Phelan considered this as if it were a philosophical question, like “Where do lost socks go?” or “Why do people save wrapping paper?”

“Somebody began to stand,” she said. “And then it would have been rude not to.”

This, Alice thought, was the sort of logic that could explain wars.

She walked again along the line, this time looking at faces, hands, feet, anything that might reveal a clue. People shuffled now and then, not forward, not back, only sideways and within themselves, as if their bodies were practicing patience.

A small sound came from further along, the kind of sound a queue makes when it decides to move. A soft ripple of shoes, a tightening of attention, a tiny collective lean.

Alice turned her head.

The line moved forward, perhaps the length of a brick. People stepped smoothly, carefully, as if the space they were leaving might bruise if abandoned too harshly.

Mrs Phelan advanced. The front of the queue was now closer to the shop door. In another moment, Mrs Phelan would reach the handle.

But she did not reach for it.

She simply stood there, a fraction of an inch from the door, and waited.

Alice looked about quickly, expecting someone to appear with keys, or a bell, or a paper list, or a reason. Nothing appeared. The street was still. The mist hovered. The reindeer in the ditch continued to stare at the sky.

Alice felt an uncomfortable sensation, as if the village itself were holding its breath.

“Excuse me,” she said to a woman in a blue coat, “did the queue move?”

The woman nodded.

“Yes,” she said.

“Why did it move?”

“Because it was time to move,” the woman replied, and then added, very kindly, “It is important to keep up.”

“Keep up with what?”

“With the queue,” the woman said.

Alice walked along to the boy she had noticed earlier. Children, she had found, were often more helpful than adults, because they had not yet perfected the art of saying things that sounded like answers.

“Hello,” Alice said, crouching slightly so she could see him properly. “Do you know what everyone is waiting for?”

The boy looked up at her, and Alice saw at once that he was tired in a peculiar way. Not the sleepy sort of tired, nor the bored sort, but the sort of tired one might be if one had been politely pretending for a very long time.

“It’s for the door,” the boy said.

“What door?”

He pointed without turning his whole body, which is how you point when you are in a queue, because turning is almost the same as leaving.

“At the end,” he said.

“But the queue begins at the hardware shop.”

The boy shook his head slowly, as if he were correcting a mistake she had made with her eyes.

“No,” he said. “That’s the beginning. The end is the other end.”

Alice blinked. “The other end?”

“The front end,” the boy said. “The end end.”

This was not helpful. It was, however, fascinating.

“Have you been in the queue long?” Alice asked.

The boy’s mouth twisted, as if the question had caught on something inside him.

“I joined yesterday,” he said.

“But yesterday was New Year’s Day.”

He nodded gravely. “Yes.”

“And you are still here on the second.”

He nodded again. “Yes.”

Alice looked at him, and then at the adults around him, and then at the way the line disappeared around the corner, and she felt a coldness that had nothing to do with the weather.

“Do people go home?” she asked softly.

The boy thought.

“People do,” he said, carefully. “But the queue doesn’t.”

Alice stood up.

Her tin of plum loaf was still in her hands, and she had nearly forgotten Mrs Delaney altogether. This annoyed her, because it suggested the queue could tamper with priorities.

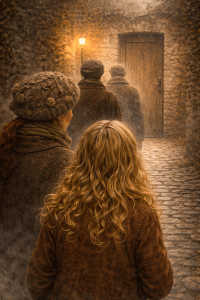

Alice began to walk toward the place where the queue disappeared around the corner. She stepped along the pavement, passing quiet faces, passing careful shoes, passing hands that held nothing as if it were something.

As she walked, she noticed something else.

Nobody in the queue held anything useful for waiting.

No books. No newspapers. No phones held up for scrolling, which in 2025 is what most people do when made to stand still. Even in Ballykillduff, where modern life sometimes arrived late and apologised, people still had phones, and still used them to show each other pictures of grandsons and sheep and suspicious puddings.

But in this queue, no one looked at anything except forward.

It was as if looking away might make them lose their place in something they could not name.

Alice reached the corner and peered around.

The queue continued.

It went past the wall, then along a narrow lane that should have led to the back of the old churchyard.

But it did not.

The lane did lead toward the churchyard, yes, but it also seemed to lead toward something else. Alice could not have said what it was. It was as if the lane had recently been persuaded to extend itself. The stones looked older than they ought. The hedge looked higher. The mist thickened in a manner that made distance feel like a suggestion rather than a measurement.

And there, far ahead, in the softened grey, Alice thought she saw a shape.

Not a person.

Not a building.

A shape that was narrow and upright.

A door, perhaps. Or the idea of a door.

Alice’s heart did a small, silly leap, because Alice had always had a weakness for doors. Doors promised answers, and answers promised more questions, and questions were the nearest thing she had to certainty.

She looked back at the line behind her.

People waited. The queue held itself carefully, as if it were a thing that could break if mishandled.

Alice took one step closer to the queue.

It was strange, but not in a dramatic way. The air around the line felt slightly different, as if the act of waiting generated its own weather. Not colder, exactly. Not warmer. Just… more definite.

She hovered at the edge, like a person approaching a river whose depth could not be guessed.

A thought came to her, sudden and mischievous.

What if she stepped in?

What if she did not?

In Ballykillduff, politeness was not merely a habit. It was a kind of gravity. It pulled you into conversations you did not want, into cups of tea you could not refuse, into queues you did not understand.

Alice looked again at the front of the line, at Mrs Phelan waiting at a closed door she did not open. She looked along the faces, mild and resigned and oddly intent. She looked at the boy, who now stared at his shoes again, as if he were listening to something beneath them.

Alice thought of Mrs Delaney and the plum loaf. She thought of Bridget waiting at home, expecting her to return with nothing more unusual than gossip and maybe a mild complaint.

Then Alice did a thing that would have pleased nobody and intrigued everyone.

She stepped into the queue.

No one spoke. No one made room, yet she found her place as if it had been saved for her. The space accepted her without question, which was the worst sort of acceptance.

Alice stood, hands in her pockets, tin of plum loaf pressed against her coat.

She waited.

And the queue, which had existed without her, seemed to acknowledge her existence, not with warmth, but with a subtle tightening, the way a story tightens when a new character arrives.

Ahead, the mist shifted.

The distant shape of the narrow door looked a little clearer, and then a little less clear, as if it were blinking.

Alice swallowed.

It occurred to her, rather late, that the second of January was an odd day for a queue to begin.

New Year’s Day made sense. People lined up for fresh starts, for promises, for being better than they were.

But the second of January was different.

The second of January was what happened after the bravery.

It was the day the world expected you to continue.

The queue moved forward, the length of a brick.

Alice moved with it, because that is what one does in a queue.

And for the first time since stepping into the line, she felt something like a tug, gentle but insistent, as if the queue were not only in the village.

As if it were also in time.

Alice looked ahead, and in the mist, she thought she saw, very faintly, letters on the faraway door.

She could not read them properly.

But she had the uneasy feeling that she already knew what they said.

She tightened her grip on the tin of plum loaf, as if bread could protect a person from philosophy.

And she waited.

Chapter Two

In Which Waiting Proves to Be an Activity

Alice discovered, after standing still for what felt like several minutes and might have been much longer, that waiting was not the same as doing nothing.

At first, she had expected boredom. Boredom usually arrived promptly when one stood in one place with no clear purpose. It tapped you on the shoulder, yawned in your face, and suggested you think of something else. But boredom did not come. Instead, something else settled around her, quieter and more attentive, like a cat that had decided her lap would do.

The queue held its shape. The people ahead stood with their feet carefully placed, as if the stones beneath them had opinions. The people behind maintained a respectful distance that felt agreed upon rather than measured. No one spoke. No one sighed. No one looked at the sky to see if it might explain matters.

Alice shifted her weight. The queue shifted with her.

Not forward. Not back. Only in a small, collective adjustment, like a thought reconsidered.

She frowned.

“I beg your pardon,” she said to the man in front of her, who wore a brown coat that looked older than he did, “but are we supposed to say anything?”

The man turned his head a little, but not enough to face her fully. It would have been impolite to turn completely.

“I don’t believe so,” he said. “Talking makes the waiting longer.”

“How do you know?”

“I once explained myself,” he replied. “It took hours.”

This seemed unreasonable, but Alice decided not to argue, as arguments often required explanations, and she had already been warned.

She glanced down at her hands. The tin of plum loaf felt heavier than it had earlier, as if the bread inside were considering its situation. She wondered if it would still be warm when she eventually reached Mrs Delaney’s, or if Mrs Delaney would still be the sort of person who required plum loaf at all.

The thought unsettled her.

The queue moved.

This time it moved enough to notice. A clear step forward, the length of a paving stone. Shoes lifted. Shoes set down. The sound was soft but unanimous, as though the stones themselves had approved.

Alice stepped forward with everyone else, and felt it then, unmistakably.

A slight pull.

It was not unpleasant. It was not strong. It was simply there, like the sensation of being on a gentle slope you had not noticed until you tried to stand still.

She looked up. The mist ahead had thinned just enough to reveal more of the lane, and the faint suggestion of the door at the far end seemed closer, though she could not have said how much closer, or by what measurement.

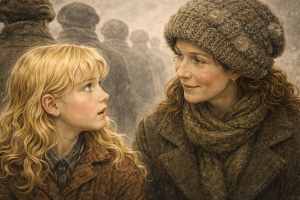

“Excuse me,” she whispered to the woman behind her, who wore a knitted hat that had been mended in several places, “do you feel that?”

The woman smiled faintly.

“Feel what?”

“As if we are being helped along.”

“Oh,” the woman said. “Yes. That’s the queue.”

“That is what queues do?”

“Only the important ones.”

This answer was not satisfactory, but it was delivered with such confidence that Alice felt rude for wanting more.

Another step forward.

Alice noticed then that time behaved differently here. She could not have said how she knew. Her watch, if she had had one, might have disagreed, or it might have refused to comment. But the feeling was unmistakable.

Moments did not pass. They arranged themselves.

She remembered, quite suddenly, a thing she had meant to finish once. It was a small thing, hardly worth remembering, and yet it pressed at her mind as if it had been waiting nearby for years.

She shook her head, and the thought retreated, though not far.

The man in the brown coat cleared his throat.

“I should mention,” he said, quietly, “that thinking too hard is discouraged.”

“Why?” Alice asked.

“Because,” he said, “some thoughts consider this an invitation.”

Alice decided to look at her surroundings instead.

The village behind her seemed further away than it ought to have been. The shopfronts were still visible, but their details had softened, as if memory had begun its work already. The wreath on the door no longer hung crookedly. It hung as wreaths did in recollections, perfectly wrong in a way that felt right.

Ahead, the lane narrowed.

The people near the front were less distinct now. Not blurred exactly, but simplified. Coats became shapes. Hats became suggestions. Alice wondered if this was what happened when one waited long enough to become an idea rather than a person.

She did not care for the notion.

“How long does it take?” she asked, because someone had to.

The man in front of her considered this with care.

“That depends,” he said.

“On what?”

“On how much you are carrying.”

Alice looked down at her tin.

“I only have bread.”

The man nodded sympathetically. “It’s not the weight,” he said. “It’s the unfinished part.”

Alice did not like this answer at all.

The queue advanced again.

She found herself beside the boy she had spoken to earlier. He looked much the same, though there was something about his posture that suggested he had grown accustomed to standing still in a way children should not have to.

“Hello again,” Alice said. “Do you remember me?”

The boy nodded.

“I remember most things,” he said. “They line up.”

“What happens when you reach the front?” she asked.

He shrugged, which took effort in a queue.

“You go on.”

“Where?”

He thought about this. “After.”

Alice closed her eyes for a moment.

When she opened them, she noticed something new. Along the stone wall to her right, small marks had appeared, scratched or etched or perhaps always there and only now noticeable. Lines. Notches. Tiny symbols that looked like tally marks, though what they counted she could not guess.

“Do you see those?” she asked the boy.

“Yes,” he said. “They’re how far.”

“How far to what?”

He smiled, and it was not an unkind smile, but it carried the sadness of someone who had been given an answer too early.

“How far you’ve come,” he said.

Another step forward.

Alice felt a brief, sharp desire to step out of the queue. Just to prove she could. Just to check whether the street still behaved as a street.

She lifted one foot.

The pull became firmer, not forceful, but insistent, like a hand offered politely and not withdrawn.

The woman behind her spoke again, gently.

“Once you lift your foot,” she said, “it’s better to put it down.”

Alice did.

The queue approved.

It was then that Alice realised something important.

The queue did not rush. It did not hurry anyone. It did not even mind if you were reluctant.

But it expected honesty.

She held the tin a little tighter.

Far ahead, the door was clearer now. Still small. Still plain. Still entirely uninterested in explaining itself.

Alice wondered, not for the first time, whether doors were ever meant to be entered, or merely approached until one understood why one had been walking at all.

The queue moved again.

Alice moved with it.

And somewhere, not behind her and not ahead, something finished waiting.

Chapter Three

In Which Faces Become Fewer

By the time Alice realised that the queue had begun to change the people inside it, it was already too late to say when the change had started.

It was not sudden. It was not alarming. It was the sort of alteration that would have gone unnoticed if one were not paying close attention, and Alice, unfortunately, had always been very good at paying close attention to the wrong things.

The man in the brown coat ahead of her still stood where he had stood before. His hat still sat at the same careful angle. His shoes were still scuffed in the same places. Yet there was something about him that felt less… occupied.

Alice frowned at the back of his head, which is the polite way to study a person without being accused of staring.

He seemed quieter somehow. Not in the sense of making less noise, as he had never made any noise at all, but in the sense of having fewer thoughts moving about inside him. It was as though some of his thinking had been asked to step aside.

The queue moved.

One step. Then another, as if it were growing confident.

Alice felt the familiar pull, gentler than a hand and firmer than a suggestion. She stepped forward without argument. The stones beneath her boots were smoother here, worn not by feet alone but by waiting.

She glanced back.

The village had retreated further than it ought to have done. The shapes of houses were still there, but their windows no longer reflected light properly. The lampposts glowed, but with the remembered glow of lampposts, not the kind that warmed your hands if you stood too close.

A man two places behind her was speaking, though he did not seem to be addressing anyone in particular.

“I always meant to finish the shed,” he said mildly. “It’s mostly there.”

No one answered him.

“I have the door,” he added. “It’s leaning against the wall.”

The queue advanced.

The man fell silent, as if the thought had been taken from him gently, with thanks.

Alice swallowed.

Ahead, the figures in the line were becoming less distinct. Their coats no longer showed buttons. Their hats no longer cast proper shadows. They were still people, certainly, but they had begun to resemble the idea of people, which was much worse.

The boy was still there.

Alice was relieved to see him, though she could not have said why. He seemed unchanged, which was suspicious.

“Do people disappear?” she asked him in a low voice.

“No,” he said. “They simplify.”

“I don’t like that,” Alice said.

“No,” he agreed. “Most people don’t.”

Another step.

Alice noticed then that the tally marks along the wall were clearer now. Deeper. More deliberate. They appeared in clusters, some scratched hurriedly, others carved with care, as if someone had wanted to make sure they would not be lost.

She reached out and ran her fingers lightly over them as she passed.

A strange thing happened.

For a moment, she remembered something she had forgotten she had forgotten. A small promise. A half-finished thought. A sentence she had never quite said aloud.

The feeling passed, but it left a faint ache behind, like a bruise pressed too gently to hurt.

She pulled her hand away.

“I think,” Alice said carefully, “that the queue is keeping things.”

The boy nodded. “It has to put them somewhere.”

“What happens if you run out of things to keep?”

He considered this for longer than she liked.

“Then you’re ready,” he said.

The word settled heavily.

Alice looked ahead again.

The door was clearer now. Still distant, still small, but undeniably a door. Its edges were sharp in a way the rest of the world no longer was. It looked solid. Certain. It looked like something that would not wait for you.

She felt a sudden, unreasonable urge to laugh, which is what happens when the mind finds itself in a place it did not intend to visit.

“This is ridiculous,” she muttered. “Queues are for shops and trains and mistakes.”

The woman in the mended hat was still behind her. Alice could feel her presence, steady and patient.

“Yes,” the woman said softly. “This one is for after.”

Another step forward.

Alice felt something loosen then. Not a thing she could name, but something that had been held too tightly for too long. It was not painful. It was almost a relief.

That frightened her.

She looked at her tin.

The plum loaf inside had gone quiet. She could not remember when she had last thought of Mrs Delaney. This troubled her more than anything else so far.

“Excuse me,” Alice said, louder than she meant to, “but if I leave now, would I still be me?”

The man in the brown coat turned his head slightly for the first time. Just enough for Alice to see his profile.

His face was perfectly ordinary.

That was the problem.

“I expect so,” he said. “But you might have to go back and collect a few things.”

“What things?”

He smiled faintly. “The ones you were standing here to finish.”

The queue moved again.

Alice stepped forward with it, because that was what she had been doing, and habits, once formed, were difficult to break.

The people ahead were fewer now. Not fewer in number, but fewer in detail. Their outlines softened. Their individuality thinned, like ink diluted too many times.

Alice held herself very still, as if stillness might preserve her edges.

She thought of plum loaf. She thought of Bridget. She thought of the first moment she had noticed the queue, and how ordinary it had seemed.

She wondered how many ordinary things had begun this way.

Far ahead, the door waited.

And behind her, the queue did not shorten.

It never did.

Chapter Four

In Which the Queue Is Found to Have Opinions

Alice had begun to suspect that the queue was listening.

This was not because it leaned closer when people spoke, or because it answered questions in words. It was subtler than that. It listened in the way floors listen for footsteps and letters listen for ink. It paid attention when things were nearly said.

The realisation came to her when she tried, for the third time, to remember Mrs Delaney’s face.

She could remember Mrs Delaney’s voice perfectly well. She could remember the way Mrs Delaney said ah when things were not going to improve, and oh when they were. She could remember the smell of Mrs Delaney’s kitchen, which was always faintly of boiled sweets and disapproval.

But the face would not come.

Alice frowned, annoyed with herself. Faces did not simply vanish. They stayed put. They were loyal things.

The queue moved.

The tug was stronger now. Not sharper, but more confident, like something that had decided it was no longer necessary to ask.

Alice stepped forward, because stepping backward did not seem to be one of the available options.

The people ahead of her were very quiet indeed. Not politely quiet, as before, but thoroughly so, as if sound had become unnecessary. Their coats were still coats, but they hung differently now, as though no one had bothered to finish wearing them.

A woman further up the line turned her head, just slightly, and for a moment Alice thought she might speak.

She did not.

The woman’s mouth opened, closed, and then settled into a shape that suggested it had once been used for conversation but had since found a better use.

“What happens,” Alice said, carefully, “if someone refuses to move?”

The boy was still beside her. He seemed smaller now, or perhaps Alice felt larger. It was difficult to tell.

“They stay,” he said.

“That doesn’t sound like refusing.”

“No,” he agreed. “It doesn’t.”

Alice considered this.

“Has anyone ever got to the front and come back?”

The boy hesitated. This was new.

“Not exactly,” he said. “Some people return pieces.”

“Pieces of what?”

“Of themselves.”

This was not comforting.

Another step.

The wall beside the lane had changed. The ivy was thinner here, more careful, as though it did not wish to intrude. The tally marks were everywhere now, etched deep and close together, overlapping in places, frantic in others.

Alice did not touch them this time.

She had learned something about the queue.

It did not take things all at once.

It accepted donations.

The thought made her shiver.

Ahead, the door was much closer now. Close enough that Alice could see its grain, the way the wood had warped slightly with age, the small chip near the bottom edge as if something had once tried to stop it from closing.

It was a very ordinary door.

This made it worse.

“I don’t think,” Alice said suddenly, “that I like what the queue thinks is important.”

The woman in the mended hat spoke, for the first time in a while.

“It isn’t interested in liking,” she said. “Only in finishing.”

“That’s not the same thing at all.”

“No,” the woman said gently. “It isn’t.”

The queue moved again.

Alice felt something leave her then. Not a memory, exactly, but the urgency of a memory. A sense that something must be done soon or else. The else no longer mattered.

She clutched the tin instinctively.

The plum loaf inside had changed. She could feel it. Not stale. Not spoiled. Simply… neutral. As if it had forgotten why it had been baked.

Alice stopped walking.

The queue did not.

For one brief, alarming moment, she felt herself being carried, her feet moving because the space beneath them insisted.

“No,” she said aloud.

The word sounded strange, as if it had not been used in some time.

The people around her paused. Not in sympathy. In assessment.

The tug did not stop, but it loosened slightly, as though the queue were curious.

Alice stood very straight.

“I am not finished,” she said.

The sentence echoed oddly, not through the air, but through the line itself. The people ahead shifted. The people behind leaned forward a fraction.

The boy looked up at her, his expression unreadable.

“That makes things slower,” he said.

“I don’t mind,” Alice replied. “I’ve been told waiting is an activity.”

The queue considered this.

It did not hurry her. It did not pull harder.

It simply waited.

For the first time since Alice had stepped into it, the queue was not leading.

It was watching.

And far ahead, the door remained closed, as if it, too, were interested to see what Alice would do next.

Chapter Five

In Which the Queue Is Discovered to Be Selective

Alice slept that night, which surprised her.

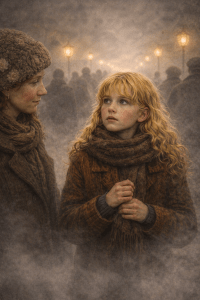

She had not left the queue, and yet night arrived all the same, as if time were determined to continue whether or not it was invited. Lamps along the lane glowed more warmly, the mist thickened, and the people around her acquired the softer outlines of those who had been standing for a very long time.

No one lay down. No one sat. The queue did not permit such things. Yet sleep came anyway, shallow and careful, like a guest who did not wish to be noticed.

Alice dreamed of shelves.

They stretched in all directions, tall and narrow, packed with objects that did not belong together. A single glove rested beside a birthday candle. A letter without an envelope leaned against a cracked teacup. Names were written on tags, but the tags were blank.

When she woke, she was still standing.

The queue moved.

Alice blinked, disoriented. The dream clung to her thoughts like cobwebs. She felt as though she had misplaced something important during the night and could not remember where she had put it.

She looked down at the tin.

It was lighter.

Not empty, but lighter, as if some of its importance had been carefully removed and stored elsewhere. The lid still fitted properly. The loaf inside was still bread. But it no longer felt urgent.

“That’s new,” Alice murmured.

The woman in the mended hat nodded. “The queue doesn’t take what you need yet.”

“That’s very considerate of it.”

“It has rules,” the woman said. “They change.”

The queue advanced another step.

Alice noticed then that not everyone moved with it.

A man further along the line remained where he was, his feet planted firmly on the stones. The space ahead of him opened, waiting politely.

The queue paused.

This had never happened before.

Alice felt a tightening in the air, as if something had become interested.

The man cleared his throat.

“I think,” he said, with careful courtesy, “that I shall stay here.”

The queue did not argue.

It simply waited.

The people behind the man felt the pull ease, then shift. Alice found herself stepping forward slightly, not because she had been told to, but because the space ahead of her had become… available.

The man remained.

He smiled faintly, as if pleased with a private decision.

“I’m not finished waiting,” he said. “But I am finished giving.”

The queue considered this.

Alice could feel it now, not as a force, but as an attention. The line was listening, weighing, adjusting.

Very gently, very politely, the queue moved around the man.

Not past him.

Around him.

The stones shifted. The lane bent. The line curved, leaving the man standing alone in the centre, perfectly still, perfectly content.

Alice stared.

“Does that happen often?” she asked.

The boy shook his head. “Only when someone knows what they are holding.”

The queue straightened again.

The man was no longer in it.

He did not look lost.

He looked finished.

Alice’s heart beat faster.

“So you can leave,” she said.

“Yes,” said the woman in the hat. “But you have to choose what stays with you.”

Alice tightened her grip on the tin.

She wondered what the queue would take next if she did nothing. A face. A feeling. A reason.

The door ahead loomed larger now, its surface catching the lamplight in a way that made it seem almost warm.

Alice did not trust that.

The queue moved again, and she moved with it, but something had changed.

For the first time, she was not entirely certain she was being led.

She might, she realised, be being invited.

Chapter Six

In Which Something Is Reached

By morning, the mist had thinned enough for Alice to see the door properly.

It stood at the end of the lane, just beyond the place where the stones changed colour and the air felt quieter. It was not impressive. It did not glow. It did not hum or whisper or breathe in any way that might have warned a sensible person to be cautious.

It was simply a door.

Wooden. Plain. Narrow. The sort of door one might expect to find at the back of a shed, or the side of a building that preferred not to be noticed.

This troubled Alice far more than if it had been grand.

The queue had shortened.

Not from behind. Behind her, the line still stretched back into fog and memory, into people who were now little more than coats and patience. But ahead of her, there were only three people left.

The boy was gone.

She had not seen him leave. She had not seen him move forward or step aside. He had simply not been there when she looked for him, which was how the queue did things when it wished to be efficient.

The woman in the mended hat stood directly in front of Alice now. Her shoulders were relaxed, her posture settled, as if she had finally reached a place she recognised.

“Is this it?” Alice asked quietly.

The woman nodded. “This is where it asks properly.”

“Asks what?”

“Whether you’re finished.”

The queue moved.

Only a fraction. Barely enough to notice. But Alice felt it all the same, a gentle pressure at her back, not unkind, not forceful. Encouraging.

She took a step forward and found herself beside the woman rather than behind her.

This had never happened before.

The queue did not correct it.

“Is that allowed?” Alice asked.

The woman smiled, and for the first time there was something unmistakably relieved in her expression.

“It doesn’t mind,” she said. “Not anymore.”

They stood together now, side by side, facing the door.

The third person ahead of them was a man Alice did not recognise. His coat was neatly buttoned. His shoes were clean. His hands were empty. That, Alice thought, might have been the most unsettling thing of all.

The man reached the door.

He paused, as everyone did, though Alice suspected the pause was not required. It was simply expected.

He placed his hand on the handle.

For a moment, Alice thought he might turn around and say something. Offer advice. Deliver a warning. Make a small joke, as people often did at the edges of things they could not return from.

He did none of these.

He opened the door and stepped through.

The door closed.

There was no sound.

The space where the man had been did not remain empty. It simply stopped being a place one could stand.

The queue shifted.

The woman in the mended hat was next.

She looked at Alice, really looked at her, as if committing her face to memory in a way the queue would not interfere with.

“I hope,” she said, “that you keep something.”

“I intend to,” Alice replied, though she was no longer certain what that meant.

The woman nodded, satisfied.

She stepped forward, opened the door, and went through.

Again, the door closed without comment.

Alice was alone at the front of the queue.

The lane behind her felt very long.

She looked down at the tin in her hands. It was heavier again. Not with bread, exactly, but with importance. With insistence. With something that wanted to be taken somewhere else.

She did not move.

The queue waited.

Alice became aware, then, of the question. It was not spoken. It was not written. It did not even feel like a sentence.

It felt like an expectation.

Are you finished?

Alice thought of Mrs Delaney. Not her face, but her voice, sharp and particular. She thought of Bridget, of plum loaf, of being sent on an errand that was supposed to be simple. She thought of noticing things, of asking questions that did not behave, of standing at the edge of things rather than stepping neatly through them.

She thought of waiting.

“No,” Alice said aloud.

The word landed firmly, as if it had been waiting for her to say it.

The queue did not argue.

The pressure at her back eased. The air shifted. The lane felt, for the first time, like a place rather than a direction.

The door remained closed.

Alice turned around.

The queue stretched behind her, patient and unchanged. But now, she noticed something new. Small gaps. Gentle bends. Places where people stood slightly apart, as if considering their own answers.

Alice stepped back into the line.

It accepted her without comment.

She was no longer at the front.

She was somewhere in the middle, which felt, unexpectedly, like the right place to be.

The queue moved.

And this time, Alice moved with it, not because she was being led, but because she had chosen to keep waiting.

Chapter Seven

In Which the Queue Learns to Breathe

By morning, Alice realised that the queue had acquired a rhythm.

She had not noticed it before, perhaps because she had been busy thinking about sleep, or time, or the fact that no one ever seemed to cough. But now it was unmistakable. The line inhaled. The line exhaled.

It did so slowly, politely, as though anxious not to disturb itself.

When the breath came in, the queue tightened by the smallest degree. Coats brushed coats. Shoes crept forward until toes almost touched heels. When the breath went out, space returned, not enough to step away, but enough to remember that space had once existed.

Alice tested this discovery carefully. She leaned forward during an inhale and felt resistance, firm but not unkind. She leaned back during an exhale and found herself allowed the movement, though no more than a fraction. The queue, it seemed, had opinions about balance.

She looked ahead. The man in the brown coat remained unchanged, his hat still set at its careful angle, his posture still suggesting that he had once been told to stand like that and had taken the instruction very seriously. Yet even he now moved, imperceptibly, with the breath of the line.

Alice wondered who was breathing for them.

Mist lingered at ankle height, thinning and thickening in sympathy with the queue’s rhythm. The lamps along the lane had dimmed to a pale morning glow, their light no longer warm but steady, as though they had decided not to try too hard. Somewhere far ahead, the lane curved, though Alice could not remember seeing it curve yesterday.

“Excuse me,” she said, turning slightly to the woman behind her.

The woman blinked, as if waking from a thought she had been holding for a long time.

“Yes,” she replied, after a pause that felt carefully measured.

“Do you know,” Alice asked, “where the breathing comes from?”

The woman considered this. Her eyes drifted upward, then forward, then returned to Alice with the mild relief of someone who had found an answer they were not certain they were supposed to share.

“It used to come from us,” she said. “But that was before the queue learned.”

“Learned what?”

“How to continue.”

This seemed an answer of sorts, though not one Alice felt able to use.

She faced forward again. The breathing continued. With each inhale, the queue drew itself together, purposeful and contained. With each exhale, it released just enough tension to remain bearable.

Alice noticed something else then. During the pause between breaths, the queue did not move at all.

In that moment, time held itself perfectly still. No mist drifted. No lamps flickered. Even Alice’s thoughts slowed, hovering like words she had almost spoken.

Then the inhale came again, and everything resumed.

Alice began to suspect that if the queue ever stopped breathing, the lane itself might forget what it was meant to do.

She tightened her scarf and stood as she had been taught, breathing when the queue breathed, waiting when it waited, and wondering, with growing certainty, what might happen when they finally reached the front.

And whether the front was still there at all.

Chapter Eight

In Which the Front Is Reconsidered

The queue moved.

It was not the sort of movement Alice had been expecting. There was no forward progress, no decisive step, no sense of having earned even the smallest advance. Instead, the queue adjusted itself, the way a thought does when it realises it has been slightly mistaken.

Alice felt it first in her feet. The stones beneath her shoes shifted, not sliding exactly, but persuading themselves to be elsewhere. The pressure at her back changed. The familiar distance between her and the woman behind her altered by the width of a breath.

Somewhere ahead, a gap appeared.

It was not large. It could not have held a person. It barely qualified as a space at all. Yet the queue reacted to it immediately, tightening and relaxing in careful turns, redistributing itself so that the gap was no longer a problem but a feature.

Alice watched this with growing unease.

The man in the brown coat did not move forward. Nor did anyone else. The gap simply travelled.

It passed from one place to the next, carried along the line like a rumour. Where it went, people leaned without knowing they were leaning. Shoes lifted and settled again. Coats swayed, then stilled. No one spoke.

When the gap reached Alice, she felt an unmistakable tug, as though the queue were checking her weight.

She held her ground. The gap slipped past her anyway, sliding behind her shoulder and onward, leaving her precisely where she had been before.

Alice exhaled, realising only then that she had been holding her breath longer than was sensible.

She looked ahead, trying to see the front.

The lane was narrower now. She was sure of it. The lamps seemed closer together, their pale light overlapping until it became difficult to tell where one ended and the next began. The mist thickened, rising from ankle height to knee, to waist, as though attempting to learn something about the people it surrounded.

And still, the front did not appear.

“I think,” said Alice, very quietly, “that we are not getting closer.”

No one answered.

Yet she felt, quite distinctly, a mild correction pass through the queue, like the disapproval of a rule that had nearly been noticed.

The line breathed in.

The line breathed out.

And somewhere far ahead, beyond the curve that Alice could no longer remember arriving at, the idea of the front shifted slightly, as if it had decided to wait a little longer before making itself known.

Alice tightened her scarf once more and stood still.

The queue, it seemed, preferred it that way.

Chapter Nine

In Which Time Becomes Selective

After a while, Alice noticed that time had begun to behave oddly.

This was not immediately alarming. Time had been peculiar ever since she joined the queue. It had arrived without asking, departed without warning, and once or twice appeared to be standing behind her, clearing its throat. But now it seemed to have developed preferences.

Some moments lingered.

Alice would lift her foot to ease the pressure on her heel, only to find herself holding it there far longer than expected, suspended in a second that refused to end. A flicker of lamp-light would hover, neither brightening nor dimming, as though waiting for permission to proceed.

Other moments vanished entirely.

Alice was certain she had just thought of something important. A question, perhaps, or a memory involving a warm room and a chair that did not mind being sat upon. Yet when she reached for it, it was gone, removed so neatly that it left no outline behind.

The queue remained unconcerned.

It breathed. It adjusted. It redistributed its weight with the patient assurance of something that had decided it was eternal.

Alice tested time cautiously. She counted the lamps ahead of her, then counted them again.

There were more.

Not suddenly, not dramatically, but undeniably. Where there had been eight, there were now ten. Or perhaps there had always been ten, and Alice had simply misremembered. The trouble was, she could no longer tell which explanation was worse.

She turned her head slightly, meaning to ask the woman behind her how long they had been waiting.

Before she could speak, the woman said, “Not long.”

Her voice was gentle, almost apologetic.

Alice frowned. “I didn’t ask yet.”

“I know,” said the woman. “That’s how it usually happens.”

“How long is ‘not long’?” Alice asked.

The woman considered this with great care. “It depends,” she said at last, “on whether you are measuring from when you arrived, or from when the queue decided you belonged to it.”

Alice felt a quiet chill at this, one that had nothing to do with the cold.

She looked down at her hands. They were red now, the skin roughened, as though they had been exposed to many mornings rather than one. Her scarf smelled faintly of mist, which seemed unfair, as mist had no right to leave a smell behind.

Ahead of her, someone shifted.

The movement was small, but it triggered a gentle correction through the line. Shoes adjusted. Coats settled. Time hesitated, then stepped aside to let the queue pass through it.

Alice had the sudden, unwelcome thought that if she were to leave the line now, she might discover that it was no longer the same day she had entered it.

Or that it had never been a day at all.

She stood very still.

The lamps glowed on, pale and patient. The mist continued its careful observations. And time, having made its selections, allowed the queue to remain exactly where it was.

Which, Alice was beginning to understand, was precisely the point.

Chapter Ten

In Which Leaving Is Considered

The thought arrived without drama.

It did not announce itself or insist on attention. It merely settled beside Alice, as calm and ordinary as a coat someone had left on a chair.

I could leave.

The idea surprised her by how reasonable it sounded.

Alice shifted her weight slightly, testing the notion. The queue did not object. It continued to breathe, drawing itself together and easing apart with the steady patience of something that had outlasted many decisions.

She glanced to the side.

There was space there. Not much, but enough. A narrow strip of cobblestones lay beyond the line, damp with mist and unclaimed by feet. It looked unused, as though it belonged to a different rule entirely.

Alice imagined stepping into it.

The moment she did, the queue reacted.

Not sharply. Not unkindly. It tightened by the smallest amount, the way a crowd does when someone nearby considers standing. The pressure was gentle, almost reassuring, yet unmistakably discouraging.

Alice withdrew her foot.

“I was only thinking,” she murmured.

No one answered, but the queue relaxed again, satisfied.

The lamps flickered, not in warning, but in acknowledgement. Their pale light seemed to stretch, overlapping more than before, blurring the edges of the lane until it became difficult to say where standing ended and waiting began.

Alice realised then that leaving might not work the way she expected.

She might step out of the line only to find that the lane continued without it. Or that time, having been selective for so long, might choose not to notice her departure at all.

Worse still, she might leave and discover that the queue had followed her.

She looked ahead again.

The curve was closer now. She was certain of it. Not because she had moved forward, but because the idea of the curve felt nearer, as though it had leaned in slightly, curious.

The people ahead remained faceless, their outlines softened by mist and patience. They stood as they always had, waiting for something that had never quite introduced itself.

Alice tightened her scarf and stayed where she was.

Leaving, she decided, required more certainty than waiting.

And certainty, like the front of the queue, had yet to make an appearance.

Chapter Eleven

In Which the Queue Notices Alice

Alice became aware of it gradually.

At first, it was no more than a feeling, like standing beneath a high ceiling and sensing that someone had begun to look down. The queue continued as before. It breathed. It adjusted. It waited. And yet something in its waiting had shifted.

Alice shifted her hands inside her sleeves.

The movement travelled farther than it should have.

A faint tightening passed along the line, not everywhere, but nearby. Shoes settled. A coat sleeve brushed her elbow and did not quite withdraw. The space around her felt newly measured.

She kept her eyes forward.

This, she suspected, was important.

The lamps held their pale glow, but the mist responded differently now. Where it had once drifted without preference, it lingered around Alice’s knees, rising and thinning as though considering her shape.

She did not step aside. She did not speak.

Still, the queue adjusted again.

The man in the brown coat ahead of her inclined his head, just slightly, not turning, not acknowledging her directly, but making room for the idea of her presence. It was the sort of movement one might make if reminded of a rule that had been temporarily forgotten.

Alice understood then that the queue had always known she was there.

What had changed was that it had begun to account for her.

The realisation was not frightening, exactly. It was more unsettling than that. It suggested a kind of attention that did not require approval or interest, only recognition.

Alice thought of the narrow strip of cobblestones beside the line. The unused space. The different rule.

The thought did not go unnoticed.

The queue breathed in.

It breathed out.

The rhythm remained steady, but Alice felt its timing shift, aligning itself with her own breath, as though checking for consistency.

She slowed her breathing.

So did the queue.

The lamps flickered once, very faintly, and then held.

Alice had the curious sense that something had been decided, though no announcement followed and nothing moved forward.

Whatever waited at the front had not changed.

But the queue, she realised, was no longer waiting in quite the same way.

And neither was she.

Chapter Twelve

In Which a Rule Is Tested

Alice did not decide to act.

That was the first rule she tested.

The idea arrived, lingered, and passed through her like the mist, leaving no clear edge where it had begun. When she moved, it felt less like a choice and more like a continuation of something that had already started.

She adjusted her footing.

It was a small thing. No step was taken. No boundary crossed. She merely placed her weight a little differently, allowing one shoe to rest nearer the unused cobblestones beside the queue than before.

The queue noticed.

Not immediately, but thoroughly.

The breathing faltered, just enough to be felt. A pause lingered between inhale and exhale, stretched thin as a held thought. The mist froze in place, suspended around coats and hems, as though waiting for instruction.

Alice did not look down.

She kept her gaze forward, toward the curve in the lane that felt closer than it had any right to be. The lamps burned steadily, their pale light no longer overlapping quite so generously.

The strip of empty stones remained beside her.

It did not widen. It did not retreat. It simply existed, patient and unclaimed.

Alice shifted her weight again.

This time, the queue reacted more clearly. A subtle correction rippled through the line, not to prevent her movement, but to contain it. Space adjusted around her ankles. The pressure at her back changed, careful and precise.

It occurred to Alice that the queue was not afraid of her leaving.

It was afraid of what would happen if she learned she could.

She let her heel hover over the boundary between waiting and not-waiting. The sensation was strange, as though the ground itself were undecided whether it should support her.

For a moment, nothing happened.

Then the queue breathed in.

It breathed out.

And did not resume its rhythm.

The stillness that followed was not empty. It was attentive.

Alice lowered her foot.

Not into the empty space, but back where it had been.

The breathing resumed at once. The mist loosened. The lamps softened their light again, relieved.

Alice understood the second rule.

Some things could be tested without being broken.

Others, once crossed, could not be returned from.

She stood quietly in the queue, exactly where she had always been.

But the knowledge remained.

And the queue, having felt it too, waited differently now.

Chapter Thirteen

In Which the Rhythm Is Altered

Alice did not move her feet.

That would have been too obvious. The queue was prepared for feet. It understood shoes and pressure and the mathematics of standing exactly where one was meant to stand.

Instead, Alice changed something smaller.

She breathed out.

Not when the queue did, but a moment later.

The difference was slight. Anyone watching would have missed it. Even Alice was not certain, at first, that she had done anything at all. Yet she felt it immediately, the faint loosening in her chest, the quiet certainty that she had placed her breath somewhere it was not expected.

The queue inhaled.

Alice did not.

The queue exhaled.

Alice had already finished.

For the first time since she had joined it, the rhythm failed to align.

Nothing dramatic followed. No ripple passed along the line. No correction arrived. The lamps did not flicker. The mist did not pause in its drifting.

And yet, something had shifted.

Alice sensed it in the space around her shoulders, which felt less precise than before. The careful pressure at her back softened, as though the queue were uncertain how firmly it should continue to hold her in place.

She breathed again, deliberately slow.

This time, the queue hesitated.

The pause between its breaths stretched, thin and uncertain, like a rule that had been written down but never tested. The mist wavered, rising unevenly now, no longer quite sure where it ought to linger.

Alice did not look around. She kept her gaze forward, her posture unchanged. To all appearances, she remained exactly as she had been.

But the rhythm was broken.

The woman behind her shifted, then stilled, as though she had felt something brush past her that could not be named. Somewhere ahead, a lamp dimmed slightly more than the others, then corrected itself.

The queue breathed again.

Alice did not follow.

It occurred to her, then, that the queue could tolerate almost anything except independence so small it did not announce itself.

Rules could bend around steps and turns. They could adapt to questions and even to doubt. What they struggled with was quiet refusal that did not seek permission.

Alice felt no triumph. Only a calm, steady certainty.

She was still in the queue.

But she was no longer entirely part of it.

The lane stretched ahead, pale and misted and unresolved. The front remained unseen. The waiting continued.

Yet Alice understood now that something essential had been returned to her, something the queue had borrowed without asking and had never quite learned how to keep.

She breathed once more, entirely on her own.

And the queue, for the first time, had to decide whether to notice.

Chapter Fourteen

In Which the Queue Falters

The change did not spread evenly.

If Alice had expected the queue to respond all at once, she would have been disappointed. Nothing so decisive occurred. Instead, the line began to behave unevenly, as though different parts of it had received different instructions.

The breathing resumed, but imperfectly.

Near Alice, the rhythm was uncertain. The inhale came a fraction too soon, the exhale lingered longer than before. Farther along, the queue continued as it always had, steady and unquestioning, unaware that anything had been disturbed.

Alice stood within the fault line.

She could feel it beneath her feet, not as movement, but as disagreement. The stones no longer seemed entirely convinced they belonged to the same surface. The mist, too, had grown selective, thickening around some figures while leaving others strangely clear.

A man two places ahead shifted his stance.

Nothing corrected him.

He glanced down, puzzled, then forward again, reassured by the familiar sight of waiting backs. But the moment had already passed. A rule had failed to arrive on time.

The lamps flickered, uneven now. One held its pale glow while the next dimmed, then brightened again, as if checking whether it was still required to do so. Their overlapping light no longer blended smoothly. Edges appeared where none had existed before.

Alice breathed.

The queue answered late.

She became aware, then, of something she had not felt since entering the line: distance. The space between herself and the woman behind her was no longer perfectly measured. It widened by the smallest amount, enough to notice, enough to exist.

The woman did not step forward to close it.

Instead, she hesitated.

Her brow furrowed, just briefly, as though a thought had nearly formed and then decided against itself. She remained where she was, hands folded, waiting in a way that was not quite the same as before.

Ahead, the curve in the lane appeared closer again. Or perhaps it had always been this close, and the queue had simply arranged itself to make it feel otherwise.

Alice did not move.

She did not need to.

The queue was no longer entirely certain where she belonged.

For the first time, the waiting felt optional.

And that, Alice understood, was how such things began to come undone.

Chapter Fifteen

In Which Waiting Is Left Behind

Alice stepped sideways.

It was not a sudden motion. She did not lift her foot with intent or glance down to check where it would land. She simply allowed herself to be elsewhere, as naturally as a thought changing direction.

Her shoe touched the unused cobblestones.

Nothing stopped her.

The stones were cool beneath her sole, damp with mist and unmistakably real. They did not shift. They did not question her weight. They accepted it without comment, as though they had been waiting for someone to notice them.

Behind her, the queue reacted too late.

A tightening passed through the line, hesitant and incomplete. The familiar pressure at Alice’s back failed to arrive. The careful measurements that had once held her in place found nothing to measure.

The queue breathed in.

Alice did not.

She stood fully apart now, neither ahead nor behind, neither progressing nor waiting. The mist thinned around her, losing interest. The lamps steadied, their pale light no longer stretching to include her position.

She turned.

The queue remained exactly where it had always been, stretching into the distance, faceless and patient. People stood within it as they always had, breathing when it breathed, waiting for the front that continued not to appear.

No one followed her.

No one looked at her.

Already, the space she had occupied was closing, the line repairing itself with quiet efficiency. The gap narrowed, then vanished, leaving no sign that it had ever been disturbed.

Alice felt no triumph.

Only relief.

She walked along the edge of the lane, where the rules were looser and the ground did not insist upon her attention. With each step, the sounds of waiting faded, until even the breathing of the queue became impossible to distinguish from the ordinary hush of morning.

The lane widened ahead of her, opening into something unclaimed and undecided. The mist drifted freely there, no longer tasked with observing anyone in particular.

Alice tightened her scarf against the cold and continued on.

Behind her, the queue waited on, perfectly intact.

Ahead of her, time resumed its usual, untidy habits.

And for the first time since arriving, Alice did not feel late at all.

Epilogue

In Which the Lane Is Remembered

Much later, Alice found herself waiting again.

Not in a queue.

She stood at the edge of a small bridge while a cart passed, paused in a doorway while someone searched for keys, waited for water to boil without watching it too closely. Time behaved as it usually did in such moments, stretching when it liked, shrinking when it was ignored.

No breathing accompanied it.

Sometimes, when morning mist lay low and the lamps were slow to fade, Alice thought of the lane. Not as it had been, but as it had felt. The careful pressure. The shared patience. The way waiting had once arranged itself so thoroughly that it seemed impossible to step aside.

She did not miss it.

Once, she thought she saw a line of people far down a narrow street, standing very still, their outlines softened by fog. She watched for a moment, curious rather than concerned.

Then the mist shifted, and the street was empty.

Alice adjusted her scarf and continued on her way.

Waiting, she had learned, was not the same as being held.

And some things, once left behind, did not need to be understood in order to remain gone.

THE END.