Those were the days

The late 1970s in Owerri were a time of electric change, not just in the air, but under the ground and in the new buildings rising along the dusty roads. The Nigerian Civil War had left scars, but the city was in a furious race to rebuild, and nothing symbolized this more than the arrival of the future: the automatic crossbar telephone exchange.

Before, telephone calls in Owerri were a ceremony. A man—it was almost always a man—would stride into the P&T (Posts and Telecommunications) office, fill out a form, and wait for a switchboard operator to manually connect his call. The operators, a special breed of human, held the city’s social and business life in their hands. They knew who was trying to reach whom, and a wrong number could be a tragedy, a missed business deal or a family crisis. The air in the exchange room was a hum of low-voiced commands, the clatter of plugs being inserted, and the soft, perpetual static of a connection being made.

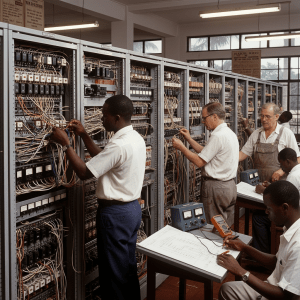

Then came the project. A team of engineers, a mix of seasoned veterans from LM Ericsson and bright, young Nigerian graduates, descended on Owerri. Their arrival was quiet at first, marked only by the excavation of trenches and the laying of thick, sheathed copper cables that snaked their way through the city’s soil. The real show began with the delivery of the equipment.

The heart of the new system was a hulking, metallic beast: the crossbar exchange. It arrived in crate after crate, a puzzle of relays, selectors, and racks. The younger engineers, like Chike, a fresh graduate from the University of Ibadan, stared at the components in awe. They had studied the theory—the marvel of the crossbar’s matrix of horizontal “select” bars and vertical “hold” bars, controlled by electromagnets that could close a connection at any intersection. But seeing the physical machine, a monument to electromechanical ingenuity, was something else entirely.

The installation was a dance of organized chaos. The exchange building, a squat, modern structure designed for the purpose, filled with the aroma of solder and fresh paint. Chike and his colleagues worked long, hot days, meticulously wiring circuits and mounting the heavy frames. Every connection was critical. A single misplaced wire could bring the entire system to a halt. The older engineers, men like Mr. Svensson, with his perpetually stained overalls and a knowing squint, offered quiet, gruff wisdom. “No hurry, boy,” he’d say to a frantic Chike. “The machine is a patient master. You must be its steady servant.”

The true test was the cutover. The day arrived with the tension of a drum being stretched tight. All of Owerri’s old manual lines were to be disconnected, and the new automatic system would come online. The P&T office buzzed with nervous energy. The operators from the old switchboard watched from the sidelines, their faces a mix of anxiety and curiosity. The old way of life was ending, and they wondered if this new, unfeeling machine could ever replicate their human touch.

Chike, his heart pounding, stood before a panel of blinking lights and switches. At the command of the project manager, a new, younger man from Lagos, he flipped a master switch. A soft, continuous hum filled the room—the sound of the crossbar exchange coming to life. It was a sound that would soon become the ambient soundtrack of modern Owerri.

Then came the calls. Not routed through a human, but through the whirring, clicking logic of the machine. The first call was a simple test, from the P&T office to the Government House. Chike watched as a series of lights on the panel lit up, relays clicked in rapid succession, and a clear connection was established. The line was crisp, with none of the old static.

Word spread like wildfire. A man in Aladinma estate could now dial his brother’s number in Ikenegbu and be connected almost instantly, without speaking to a third party. The new exchange didn’t ask “Who are you calling?” or “Is it urgent?” It simply made the connection.

The city adapted quickly. The distinctive dial tone became a familiar sound. The new, five-digit telephone numbers were scrawled in notebooks and memorized. The crossbar exchange, a technological marvel of its time, was more than just a piece of equipment; it was a symbol of Owerri’s future. It connected the city to itself, and in time, to the wider world, paving the way for the digital age that lay just over the horizon. The clicking of its relays was the sound of progress, a mechanical heartbeat in the new, vibrant city of Owerri.