The Tullow Turnip Terror

The Tullow Turnip Terror

Dramatis Personae

- Turlough the Turnip — A colossal, speaking root with mayoral ambitions.

- Tommy Doyle — A sharp thirteen-year-old with more nerve than sense.

- Mrs. Brigid Kavanagh — Rhubarb queen, opinion cannon, veteran of seventeen gardening trophies.

- Mick Byrne — A taciturn grower whose “special feed” starts everything.

- Sergeant Flanagan — The weary Garda who’s seen it all (until now).

- Father Pádraig — Parish priest with a soft spot for boiled veg and choir practice.

- Máire Lennon — Councillor, chair of Tullow Tidy Towns, fond of clipboards.

- Breda Nolan — Local radio host, voice like warm toast.

- Declan O’Connor — Publican; proprietor of O’Connor’s, where news ferments.

Chapter One: The Hum in Market Square

The year the weather forgot itself, Tullow’s Gardening Competition bulged at the seams. The square glittered with jam jars, carrot towers, and a cabbage arranged like a bishop’s mitre. Mrs. Kavanagh patrolled her rhubarb like a general, tapping stalks with a teaspoon to judge tone.

Mick Byrne arrived late, pushing a wheelbarrow that creaked like a funeral cart. Inside lay the turnip—purple, monstrous, and faintly… throbbing. Folks swore they could feel its vibration through their shoes. Children reached to touch its skin and yanked their hands back, startled by a pulsing warmth.

“Big yoke,” said Sergeant Flanagan, because words seemed inadequate.

At noon, when the judges leaned in, the turnip began to hum. Low and steady, the note quivered pint glasses in O’Connor’s and made dogs put their paws over their ears. Breda Nolan, broadcasting from the steps of the Town Hall, stuttered live on air. “We appear to be experiencing… vegetable interference.”

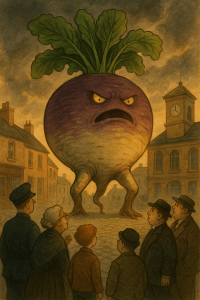

The hum deepened. A throng gathered. The leaves at the crown quivered like a pompous wig. Then, with the slurp-pop of a cork, two thick roots tore free and slammed onto the cobbles. The turnip stood.

Someone laughed time’s last nervous laugh.

Then the turnip said, “Ahem.”

Chapter Two: Turlough Declares

“I am Turlough of the Soil,” the turnip announced in a voice like a bog being dug. “Long have you peeled my kind. Long have you boiled us to death. Today, the root speaks.”

Mrs. Kavanagh crossed herself with her teaspoon. “Blasphemy in brassicas.”

Turlough shuffled forward, each step cracking a flagstone. He loomed at the Town Hall doors and knocked them politely off their hinges. Out came Mayor Hennessey in his chain, blinking.

“I demand recognition,” Turlough said. “I demand a vote.”

The mayor fumbled for statesmanship, found none, and offered carrots instead. Turlough frowned. “Bribery will not be tolerated.”

From O’Connor’s doorway, Declan called, “You’ll never be mayor without kissing a baby.” Turlough leaned down toward Tommy Doyle. Tommy gaped. “Ah—no thanks,” he said, backing into a sandwich board that declared TRY OUR NEW GARLIC MAYO! Garlic sent a visible shiver through Turlough’s leaves.

“I will purchase advertising,” Turlough decided. “We begin at once.”

By evening, posters were everywhere: VOTE TURNIP—STRONG ROOTS, FIRM LEADERSHIP. The hum never ceased. It threaded lanes, seeped under doors, and made kettles boil a second sooner than expected.

Chapter Three: The Campaign Trail (Compost Promised)

Breda Nolan’s radio show snagged the exclusive debate: the mayor, Councillor Máire Lennon, and Turlough, who spoke through the studio window because the door was too small.

“What’s your plan for Tullow?” Breda asked, professional as a saint.

“Free compost for all. Amnesty for bruised produce. An end to boiling,” Turlough intoned.

The square erupted in argument. Father Pádraig muttered, “An end to boiling? And what, steam us into perdition?” Meanwhile, Máire Lennon scribbled notes. “Can a root crop hold office? What’s the legal standing of a tuber—root? Is it a tuber? Someone check.”

That night the gardens shifted. Potatoes rolled like marbles. Beetroot trundled in pairs. Leeks bowed and shuffled along the hedges, muttering about unionization. Cats refused to chase anything that hummed.

By dawn, a column of vegetables had taken the church steps. They attempted a hymn. Their pitch was “compost heap.” It was terrifying, and very slightly moving.

Chapter Four: Night of the Rolling Spuds

Sergeant Flanagan led a patrol to the Carlow road. They found barricades—celery lashed together with bean tendrils, pumpkins stacked like cannonballs, a cabbage turret turning slowly to track them.

“Back it up,” he said, softly. “Back it up now.”

Back in the square, Turlough delivered another speech from the Town Hall balcony, the mayor’s chain looped stylishly over his crown-leaves. “Tullow will be the first Root Democracy. In time, Carlow and Kildare shall sprout. We shall send ambassadors to Dublin. They will travel by wheelbarrow.”

The crowd wasn’t sure if that was a joke. Then a rain of baby carrots pelted their shoes. “Ah sure that’s grand,” someone said, pocketing three.

In O’Connor’s, the lock-in turned grim. “If they block the roads, we’ll run out of Tayto,” Declan said. The room murmered with true fear.

Chapter Five: Siege of Tullow

By Thursday, Tullow was sealed in. The school closed after juniors were attacked by a militant broccoli head preaching the dangers of melted cheese. The chipper stayed open, because nothing earthly can stop a chipper, but the chips began whispering secrets as you ate them.

Tommy sat with his bag of chips, hearing them murmur, “He knows. He planted it.” He looked up at Mick Byrne, who stood at the door like a guilty scarecrow.

That night, Tommy followed Mick to the allotments by the river. There, under a corrugated shelter, Mick lifted a tin and winced at a label: GrowFaster-Plus (Experimental): For Research Use Only. Inside lay a slurry the colour of old bruises and… something else: smooth, pale stones etched with spirals, dug from the bog.

“Found the stones at Drumbawn,” Mick whispered, confessing to the moon. “Gave the turnip the feed. Wanted to win a cup. Didn’t want to wake the ground.”

The ground hummed.

Chapter Six: The Cult of the Root

A small but enthusiastic human faction formed: Friends of the Root. They wore green sashes and said things like, “It’s time to move beyond salads as mere side dishes.” Máire Lennon, desperate to keep the town tidy, suggested designating pedestrian veg lanes. The cabbages refused; “We roll where we wilt.”

Father Pádraig organised a debate in the parish hall: Boiling—A Moral Catastrophe? Turlough attended by putting his crown-leaves through a window and booming from the car park. When the priest quoted scripture, Turlough quoted soil pH levels.

The hum grew louder. Old people’s dentures chattered in their glasses. Milk curdled in the fridge and came out pre-soured, which Mrs. Kavanagh said was “handy for baking but terrible for civilisation.”

At midnight, Tommy and his best friend Sinéad crept back to the allotments with a torch and a pilfered magnifying glass. The spiralled stones glowed faintly when the torchlight hit them. Beneath the shed, the soil throbbed like a heartbeat.

“Not just science,” Sinéad whispered. “Old magic… or new trouble.”

Chapter Seven: O’Connor’s Last Lock-In

The vegetables attacked the pub, because that’s how you break a town. A parsley phalanx climbed the steps. A parsnip battering ram smacked the door. Inside, Declan issued hurleys. “For Tullow!” he snarled, smacking a marrow that tried to wedge itself through the letterbox.

Father Pádraig swung with surprising skill. “I’ll give you penance,” he told a celery stick, cracking it into soup.

The pub windows rattled with the hum. Bottles sang. A potent smell rose from the floorboards: stale ale, fear, and… butter. “Where’s that butter smell coming from?” Declan yelled.

Tommy’s eyes widened. Butter. He thought of steam and Sunday dinners. He thought of pressure and pride. An idea sparked, mad and simple.

“We need the big pot,” he said.

Chapter Eight: The Rally on the Steps

Morning brought a rally. Turlough announced a referendum: SHALL TULLOW BE RULED BY THE ROOT? The Friends of the Root clapped and sprinkled compost over themselves like confetti. Máire Lennon tried to take minutes but her pen grew a tiny leaf and refused to write anything unflattering.

“Today,” Turlough declared, “we formalise respect.”

The hum concentrated into a note you could lean on. People swayed. A few knelt. Tommy felt it pulling at his knees like a tide. He clutched Sinéad’s sleeve and whispered, “We’ve one shot.”

He looked at the Town Hall steps. He looked at the square’s centre: the old iron pot from the fair days, the one they used at the Goose Festival for boiling spuds. Too small for Turlough. But Mrs. Kavanagh had a pressure cooker the size of a holy font—she used it to make rhubarb jam in a single, terrifying whoosh.

“Brigid,” Tommy said, tugging her sleeve, “we need your monster pot.”

“You’ll scratch it,” she said automatically, then caught the look in his eye and nodded. “Right so. For Tullow.”

Chapter Nine: The Plan with the Pot

That afternoon became a heist film. Sinéad lured a brigade of carrots away by reading aloud from a cookbook (“Julienne” made them faint). Declan and Sergeant Flanagan hauled the enormous pressure cooker into the square on a dolly, puffing. Father Pádraig blessed it and then whispered to Tommy, “I’m not strictly sure this is liturgical, but needs must.”

Mrs. Kavanagh produced butter. “For morale,” she said, smearing it on crowds like war paint.

The hum vibrated coins in pockets. Turlough returned to the balcony. “You cannot prevail,” he said, not unkindly. “You will adapt. You will welcome Root Rule. It is the natural order.”

“Bite me,” said Mrs. Kavanagh, and put her teaspoon between her teeth like a knife.

Chapter Ten: Pride Before the Steam

Tommy rolled the pot to the foot of the Town Hall steps and banged on its side. “Bet you can’t fit in here,” he shouted, voice cracking. “Not mayor enough to sit where soup sits!”

The square gasped. Turlough stilled. Pride, oldest of fertilisers, did the rest. He descended with immense dignity, leaves trembling. “I fit where I choose,” he said, and positioned himself above the pot, wriggling just enough to wedge his bulk inside.

“Now!” Tommy yelled.

Flanagan and Declan slammed the lid. Mrs. Kavanagh spun the seal. Father Pádraig clamped the valve with the confidence of a man who’d fixed a thousand radiators. Sinéad ignited the gas with a match struck on the steps.

The hum changed key—confusion, then outrage, then something like… seasoning.

Steam screamed. The square smelled of Sundays and surrender. The Friends of the Root threw down their sashes and wept into napkins.

Inside, Turlough rumbled one last speech. “I was not… entirely… wrong,” he said, voice muffled by metal. “Respect… the soil.”

The hiss dwindled.

Chapter Eleven: The Mash of Victory

They waited. The square was quiet but for the tick of cooling metal. When the lid finally came off—cautiously, reverently—the crowd peered in. No teeth. No terror. Just a mountain of golden-orange mash, glossy with butter.

Declan, because he understood ceremony, fetched a wooden spoon the size of a hurley. He served from the sacred pot onto china plates pilfered from the parish hall.

They ate standing up, with tears and laughter and the shudder that comes after the worst has passed. Father Pádraig said grace. Mrs. Kavanagh dabbed her eyes and declared, “Best turnip I’ve ever tasted.”

At midnight, the barricades of celery sagged and went to seed. Potatoes rolled home like exhausted dogs. The posters peeled themselves from the walls and lay down in the gutters to mulch.

Tullow slept.

Chapter Twelve: Aftertaste

Morning brought a formally worded apology from Tullow Tidy Towns for the state of the square. The mayor presented Tommy with a medal made from a bottle cap and a ribbon cut from a sack of spuds. Breda Nolan declared it “the most delicious coup in Irish history” on air.

Life trickled back. The chipper stopped whispering. Cats resumed their yawning interest in anything that wasn’t humming. Máire Lennon submitted a motion to prohibit future candidates taller than the Town Hall doorway.

And yet.

On wind-harried evenings, when the sun lowered its head to the fields and the Slaney ran slate-coloured and sly, a soft thrum could be felt underfoot in Market Square. Not loud enough to startle. Just… present.

Tommy visited the allotments. Beneath the shed, the spiralled stones were gone. In their place, a neat hollow as if something had been carefully lifted out. Beside it, half-buried, lay a single seed the size of a chestnut, pale and faintly warm.

He cupped it in his hand and felt, or imagined, a pulse. Sinéad looked at him sideways. “We’ll plant it?” she asked, half-daring, half-terrified.

Tommy shook his head. “We’ll mind it,” he said. “And we’ll set rules.”

“What rules?”

He thought of Turlough’s last words. He thought of Sunday dinners and pride and the way the square had smelled when the lid came off. He thought about what it meant to live on a piece of land, and to draw breath from it, and to put things back after.

“Rule one,” he said. “No experiments without asking.”

“Rule two: no boiling without blessing.”

“Rule three: if it starts humming, we get Mrs. Kavanagh.”

They sealed the seed in a biscuit tin and slid it onto the highest shelf of the shed. The hum was gone—but if you put your ear to the tin, and the night was very, very quiet, you could just about hear a faint, contented purr.

And if, in five or ten years, posters appear again on a windy morning—VOTE PARSNIP—A MORE ELEGANT SOLUTION—no one in Tullow will say they weren’t warned.