The Schoolyard That Was

Back to the Playground

I had intended only to walk by the river and see what was left of the old town at low tide. Sunbury-on-Thames wears memory well; it clings to the willow leaves that comb the water, and to the flint walls that always look damp, even in sunshine. On that particular morning the Thames looked like a sheet of polished pewter, a swan cut it with a white signature, and somewhere a bell rang once and then thought better of ringing again.

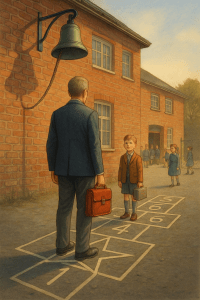

I followed the towpath past the boating club and the place where we used to dangle string with bent pins into the water and call it fishing. It was all smaller than I remembered and also somehow larger, which is the kind of arithmetic time does when it thinks no one is watching. Ahead, where Saint Ignatius’ school had been, stood a neat block of flats with balconies like teeth. Along the side wall, however, they had preserved a fragment of brickwork, the very corner where the school bell had hung. The bell was gone, but the bracket remained, a black iron question mark nailed forever to yesterday.

You may wonder why I turned in at the gate and slipped through the gap in the hedge. I could say I was only looking, only remembering, only passing an hour before lunch. But the truth was there in the air: a faint powder-sweet smell of chalk and milk-bottle foil, the ghost of cabbage from a kitchen long demolished. The sort of smell that folds a grown man up until his knees are mottled and his heart beats like an assembly drum.

On the patch of ground where the playground had been, someone had painted a modern hopscotch in factory-straight lines. But if you knelt and looked closer, as I did, you could still see the older squares faintly showing through, like bones beneath skin. The numbers were a different hand—shaky, done by some past caretaker with a paintbrush and patience.

I put my foot in the old “1,” because I always started there. As soon as my shoe touched it, I felt the world give a careful, courteous lurch, and the air crowded with voices.

“Get in line—single file!”

“Hands out of pockets, Wilson.”

“Have you brought your pencil, or shall I lend you a sense of responsibility?”

The day repainted itself around me. The flats blinked and found themselves brick classrooms with high windows. The neat hedges became a chain-link fence with the top curled over. The sky kept its blue but rinsed it lighter, as if it were 1960-something’s favourite shirt. And the bracket on the wall, that iron question mark, completed itself with a bell—our bell—fat and greenish and slightly dented, with the rope hanging down like a piece of untidy thunder.

Children poured into the playground as if the doors were taps. Boys in short trousers with bare knees that looked perpetually surprised, girls with ribbons bouncing, satchels hitting spines with hollow thumps. There was the scuff of plimsolls, the rattle of marbles in pockets, the glint of a tin lunchbox with a cowboy on it—my cowboy, with a scratch through his hat. A boy limped past with one shoe sole flapping like a tongue. A girl marched by counting, lips compressed with responsibility: “Twenty-seven, twenty-eight, twenty-nine—”

I looked down and discovered that my own clothes had joined in the game. The present had faded like a chalk diagram under sweaty palms. I wore a blazer that smelled faintly of damp cupboard, socks that refused to stay at attention, and a tie that behaved like a snake pretending to be straight. In my hand—oh—my red satchel, the one with the stiff creak and the name inside, handwritten in ink that had blotted at the “d”: Gerrard.

“Move along, new boy, you can’t stand in the doorway like a hatstand.” It was Mr. Keane, whose voice always carried a blackboard eraser in it. He swept past, trailing a cloud of chalk dust that seemed to remain in the air in words: Neatness. Discipline. Copperplate.

I moved, because I had been moving for him for decades. But I didn’t go far. I was searching for someone. I found him near the fence, a small boy with hair that could not make up its mind and a face holding the weather of four feelings at once: excitement, fear, determination, doubt. He stood with his heels together as if he had already learned the trick of holding yourself up by bravado. He hugged his lunchbox like a shield. A paper name label curled on his lapel, the scrawl clumsy but proud. I knew how his stomach felt because mine felt the same, doubled through time.

I did what all good time travellers do when faced with a paradox. I hesitated.

At that moment the bell rang, a single great “GONG,” and the sound went straight through my ribs and struck something that had been waiting fifty years to ring in sympathy. Rows formed as if a magnet had been drawn along the gravel. Our headmaster glided along their edges like a boat among reeds, tapping his cane softly against his calf in a way meant to be casual and not succeeding. This was the man who had an umbrella for rain and a cane for weather of the soul. He had an ordinary face and extraordinary eyebrows.

“Welcome, boys and girls,” he said, as if the words were the opposite. “On this, the first day of term…”

His voice drifted over us while my eyes attended to details: the white milk crates stacked in the corridor, silver caps winking; the boy picking the scab on his knee and the girl frowning at him with proprietary disgust; the way sunlight made a lane through dust as glorious as any Roman road. And then the oddest thing: the dust motes were not random, not at all. As the headmaster warmed to his theme about virtue and punctuality, the little particulates arranged themselves into letters, then words, then looping sentences that drifted like a slow aquarium of chalk phrases. I leaned in with my whole face, squinting. The words said, Mind how you walk and Please don’t trip over yesterday and Remember to breathe when you remember to remember.

The headmaster’s eyebrows twitched. He didn’t notice. Even then I thought: Isn’t that just like grown-ups? Words floating in sunbeams telling them secrets, and they prefer the reliable thud of their own voice.

The line began to move toward the classrooms, and I found myself beside the small boy with the cowboy tin.

“First day?” I asked, as neutrally as possible, which is to say with a treacherous voice that wanted to be kind and was afraid of setting the world on fire.

He regarded me from the corner of his eyes, as if measuring whether I might be a trick. “Everyone’s is,” he said, which I knew to be a lie and liked anyway.

We shuffled one, two, three steps. The gravel had a way of moving you that you could not resist. “You’ll be all right,” I said to him in a whisper that I arranged as much for myself as for him. “It’s mostly sums and chalk and the occasional catastrophe.”

“What’s a catastrophe?” he said carefully, as if it were on the spelling list.

“A thing that feels like forever for exactly as long as it isn’t,” I said, and immediately wished I hadn’t. I was never good at explaining plainly when my heart was full.

He nodded solemnly, as if I had told him the timetable. “Do we get milk?”

“We do,” I said, “and sometimes it is warm, which is the worst kind of kindness.”

He smiled at that—small, involuntary—like a fish surfacing to see if the world above is livable. We reached the doorway of Class 1. The door itself stood open like a mouth that had learned manners. Above it hung a chart with the alphabet marching in two armies: capitals and smalls. The capital Q looked as if it had misplaced its tail.

Inside, the classroom had the smell every classroom has always had: pencil shavings, floor polish, damp wool, fear, and hope. The desks were wood with lids that lifted, each with its own constellation of ink-stained stars. On the back wall, a map of the world had peeled at the edges, Africa the colour of a bruise, Australia an afterthought. Miss Carter stood by the blackboard, tall and mousy, which should be impossible but wasn’t. She possessed a kind smile she tried to conceal from her colleagues and a firm voice she tried to conceal from herself.

“Good morning,” she said, and when we murmured it back she made us do it again until the morning felt greeted rather than sidled past.

We took our places. It’s strange to sit at your own desk while also standing beside it a lifetime away, but time is an extravagantly set table. On the first chalk line she wrote WELCOME. The letters looked nervous in their best clothes.

We were copying the word, tongues out, when the first ripple went through the day. It began with a marble, green with a white curl inside, that rolled out of nobody’s pocket and followed the grain of the floor toward the front. No one had pushed it. It wasn’t even rolling downhill. It simply wanted to be somewhere else. Then another marble rolled, and another. Soon a serious procession of small glass planets were migrating with the dignity of a river toward Miss Carter’s shoes. She looked down and lifted her hem just in time to avoid a skirmish with the planet Neptune.

“Who is responsible for this—” she began, and the chalk in her hand drew the rest of the sentence without permission: river. The chalk paused, surprised at itself, then carried on and drew Thames in a slow, watery script so lovely that for a moment I could hear swans.

I felt it then, the same sense I have sometimes had when the wind changes and the willow leaves show their paler undersides: a turning of a page you hadn’t noticed you were reading. Time had not merely folded me into it like an extra note; time had decided to play.

At break we were let out into the flawless chaos of the yard, where games began with arguments and ended with treaties. A tall boy named Donald, blessed with elbows like ambitions, began selecting teams for football. The small boy with the cowboy tin was passed over and pretended to find that agreeable. I watched him do the pretending. I wanted to go over and rearrange the world so he would not have to. I forgot myself and took one step in that direction, and the hopscotch squares—those faded bones beneath the paint—caught my eye.

If you have ever looked at hopscotch and thought it a simple count from earth to heaven with one foot and a stone, you have never looked at it as a ladder printed on time. The old squares glimmered as if someone had rubbed them with beeswax. The numbers were a little off, backwards in places, wobbly as if the caretaker had been laughing. I picked up the marker—a flattish stone like a forgotten sandwich—and tossed it in the traditional manner. It landed not on “1” or “2,” but past “9,” on a little half-square labelled with a tiny star. I don’t remember that star ever being there. But then again, I had not been here when I was here.

“Your go,” said a girl with the ribbons. She had an inspector’s air about her. So I went. One foot, two feet, jump the forbidden, spin at the end, come back without trespass. The moment my sole touched the star square, the bell rope gave a little shiver, just enough to wave hello, and the entire schoolyard tilted toward something that was not quite present day and not quite 1960-anything either. The tall boy Donald mis-kicked the ball, which had the texture and colour of a potato and the manners, too. The ball went sideways, caught the chain-link fence, and bounced back directly to the small boy with the cowboy tin. He trapped it on his foot with astonished competence. For a second, all the clocks that had forgotten themselves remembered him. The tall boy looked, and the rules of the playground reconsidered. “You,” he said, “you’re on my team.”

I didn’t exhale until I’d reached the chalk line again.

After break came milk, in small glass bottles, each with a silver cap dented by thumbs. Miss Carter arranged them on the windowsill where the sun insisted on making them problematic. I took mine and drank it with the bravery we found for such things. The girl with ribbons passed me a square of damp, fold-marked paper. On it was a pencil sketch of the hopscotch star, and underneath she had written, You know how to land. She was the kind of girl who always did her homework early and life late. I nodded my thanks and tucked it in my satchel, forgetting until later that it was already there, folded, with a crease exactly where hers would be.

The afternoon drifted into sums, in which the number eight looked like a snake lying down after lunch. Then handwriting, in which my present hand longed to rescue my past one. Outside, the river made the sound of a book closing and opening again. Somewhere beyond, the towpath held the clean scuff marks of our favourite racing game: “I’m winning,” “You always cheat,” “No, I’m just older.” Memory is often won by the oldest and quickest and most willing to fall.

Near three o’clock the headmaster strode in with two visitors: a new parent from somewhere far away (he might as well have been from Mars for how the room received him) and a man in a brown suit so beige that he may have been an inspector. They were an interruption with eyebrows. The headmaster’s cane clicked the floor once—just enough to tell the room what it already knew (order is a brittle thing)—and then he said, with what he hoped was graciousness, “Carry on as if we were not here.”

He might as well have commanded the river not to flow.

Miss Carter invited us to read aloud. The small boy with the cowboy tin—myself, of course—stood to read a paragraph about a rabbit (not that rabbit, another rabbit) who looked at a hole and wondered about falling. His voice was steady for five words and then remembered who it belonged to and faltered. The room glowed with that particular heat children give off when one of their own is in danger of making the day memorable in the wrong shape.

I felt myself walking forward before I decided to. I stopped by the blackboard, which smelled of old rain. “Excuse me,” I said, and then, because I was already in it, I took a piece of chalk. It felt familiar, not like holding but like being held. I drew a small star on the blackboard beside the word WELCOME, the same star that lived in the hopscotch. “If you put your foot on this,” I said to the room at large, “you can land anywhere.”

“Sir,” said the inspector-in-beige, bristling at the pronoun, “what precisely—”

But Miss Carter’s eyes were bright with that rare and generous permission teachers sometimes give when they know a moment is being born. “Let’s see,” she said softly.

The small boy looked at the star as if it were a thing he recognized from a dream and had mislaid. He swallowed, planted his foot almost invisibly, the way you do when you are testing thin ice, and began again. The words came easier. They did not fly, but neither did they insist on crawling. He finished the paragraph with a little shrug of triumph that he tried to hide by fiddling with the cowboy’s dented hat.

“Thank you,” said Miss Carter, to the small boy and to the room and perhaps to me, it was hard to tell. The headmaster harrumphed his approval at nobody in particular. The inspector examined his beige sleeve for lint and failed to find enough to justify himself. The new parent looked puzzled and then pleased for reasons we were not obliged to know.

When the final bell rang, it did not so much ring as sigh. We were released into the afternoon like a handful of marbles, each choosing a groove. I stood near the gate because I wanted to see him—me—go. He emerged with his lunchbox, empty now and somehow prouder for having served. He adjusted the satchel bravely as if it weighed as much as a future. The girl with ribbons walked beside him, explaining something important about how one should hold a pencil when one is serious about the world. He kept looking back at the school, as if to memorize the right number of windows.

Then he saw me and paused. You can’t leave your first day without saying goodbye to the person you will become, even if you don’t have a name for them yet. He came close enough for the edges of time to blur a little. “Will there be more days like this?” he asked, with an innocence that was a sword and a shield both.

“Yes,” I said. “Not the same, but yes.”

“Will I always be frightened?”

“Sometimes,” I admitted. “But then you hop to the star and you land where you need to land.”

He thought this over as if it were arithmetic in need of a quiet corner. “What should I remember?”

“Everything you can,” I said. “And forgive what you can’t.”

His face eased, the way a knot loosens when the right hand happens by. On impulse, I reached into my pocket and found a conker—the kind with a smooth brown shine as if it had been polished by being thought of too often. I didn’t remember putting it there. I pressed it into his palm. “For your pocket,” I said. “For luck.”

He nodded with grave gratitude, then ran to catch up with the girl with ribbons, who was already three adult paces ahead and counting.

The light changed then. The sky performed that trick where it becomes a color for which there is no grown-up name, and the willow leaves showed their paler undersides again, which is how I knew the page had turned. The bell rope lifted of its own accord and then dropped like a curtain coming down.

I was standing on the modern hopscotch in the half-court of the flats. Traffic hummed in the near distance, a ferrying sound of errands and obligations. The fragment of brick wall with the iron bracket leaned patiently against now. I put my hand on it and came away with a shimmer of old dust. On my palm, faintly, the mark of a chalk star.

I walked back to the river to see if the water still remembered us. It did, in its fashion. It had carried us all along in tiny pieces and was not the sort to make a fuss about it. I leaned on the railing where I had once watched men in caps haul punts and boys in uniform pretend not to watch anything at all. The conker—this is the part no one believes—was in my pocket, heavy as a truth and warm from my hand. It had the dimple where small fingers had squeezed it, a half-century echo pressed into gloss.

Later, at home, I opened the old red satchel I keep in a cupboard where important things go to rest. Inside, among hymn sheets with pencil sums in the margins and a rigid ruler with a chip off one corner, lay a piece of paper folded along an ancient crease. I unfolded it carefully. There was the pencil sketch of the hopscotch star, and underneath, in a young hand with a strong sense of certainty, You know how to land.

I stood at the kitchen window, looking out at nothing much, holding that paper and the conker, letting the past and present balance themselves like boys on a see-saw who have finally worked out the exact place to sit. I didn’t try to decide what had happened. Time doesn’t answer to cross-examination; it prefers nods.

What I could do was this: lay the conker in the blue bowl where I drop my keys, tape the paper above my desk, and write down the things I remembered before they ran too far to catch. Outside, the light was the nubbly grey of a school cardigan. Somewhere, a child laughed in that unselfconscious key that adults spend years trying to remember. I could almost hear the chalk on the board, the way it judders when you’re nervous, the way it sings when you aren’t.

The river moved on. It always does. But as I turned away I thought I had understood the thing that had always troubled me about the first day of school, and perhaps about most first days. We think we are beginning, and in a way we are, pencils new and rubbers pink. Yet we are also stepping onto a pattern already traced faintly beneath the paint, numbers and stars set down by some caretaker who laughed while he worked. The trick is not to worry whether you are the first to hop it or the last. The trick is to put your foot down where the star is, and trust that the square will meet you.

So I do what I can do best: I carry the magic forward. I keep a bell inside my chest, slightly dented, greenish with fondness. When it rings, which it does now and again, I straighten my tie as if it were not a snake at all, and I say, Good morning, until the morning feels greeted. Then I take one careful step into the day, hop to the star, and land exactly where I need to land.