The morning mist in Tullow usually smells of damp grass and the Slaney river, but on a Tuesday in October, it carried the scent of sun-baked cedar and ozone.

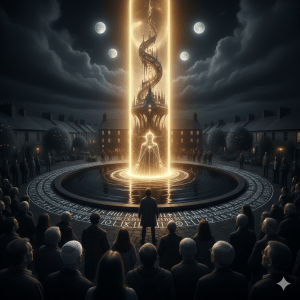

When the sun finally burned through the fog, the townspeople found it: a pyramid, no taller than a two-story townhouse, sitting perfectly centered in the middle of The Square. It hadn’t made a sound. No one’s Ring doorbell had captured a delivery truck, and the gravel beneath it hadn’t even been displaced. It looked as though it had been there for ten thousand years, and the town of Tullow had simply grown around it overnight.

The Impossible Stone

The structure wasn’t gold or limestone. It was made of a deep, matte basalt that seemed to “drink” the light around it. Local historian Sean O’Shea was the first to approach it with a magnifying glass.

“It’s not Egyptian,” he whispered to the huddle of onlookers. “The carvings… they’re Ogham, but they’re wrong. The lines are moving.”

He was right. The deep grooves etched into the stone weren’t static. If you looked at a symbol and then blinked, the notches had shifted, crawling like slow-motion insects across the surface of the dark stone.

The “Goings-On”

As the day progressed, the “mysteries” escalated from architectural anomalies to full-blown local phenomena:

- The Weightless Zone: Within ten feet of the pyramid, gravity seemed to lose its grip. Local kids discovered they could jump six feet into the air with a single hop. A stray Border Collie was seen drifting three feet off the ground, looking mildly annoyed as it paddled through the air.

- The Radio Silence: Every digital device in Tullow began to act up. Car radios played music that hadn’t been recorded yet—melodies with instruments that sounded like glass breaking in harmony. Phone screens showed maps of stars that didn’t exist in the Milky Way.

- The Echoes of the Past: At noon, the air around the pyramid grew thick. People standing near the Post Office reported seeing “shadows” of people in ancient robes walking through the walls of the modern shops. They weren’t ghosts; they looked solid, but they were silent, focused on a city that had stood in Tullow’s place eons ago.

The Door Without a Seam

By sunset, the Irish Defense Forces had cordoned off the area, but the pyramid had its own ideas about security. A seam appeared on the eastern face—not a door opening, but the stone simply evaporating into a fine purple mist.

A low hum, like a thousand bees vibrating in a cello case, began to pulse through the pavement. Those standing closest reported a sudden, overwhelming memory of a life they had never lived—a memory of a Great Library and a sky with three moons.

“It isn’t a tomb,” Sean O’Shea shouted over the rising hum as the military tried to push the crowd back. “It’s a bookmark! It’s holding our place in time!”

As the clock struck midnight, exactly twenty-four hours after its arrival, the pyramid didn’t vanish. Instead, the colors of Tullow began to bleed into it. The gray pavement turned to gold dust; the local pub’s neon sign turned into a floating orb of cold fire. The pyramid wasn’t visiting Tullow—it was starting to rewrite it.

The Morning After

The next day, the pyramid was gone. The Square was empty. But the people of Tullow were different. Everyone in town now spoke a second language—a melodic, ancient tongue they all understood but couldn’t name. And in the center of the Square, where the pyramid had sat, the grass now grows in the shape of a perfect, unblinking eye.

The transition from a sleepy market town to a high-security “Linguistic Quarantine Zone” happened in less than seventy-two hours.

The Irish Defense Forces were replaced by international suits: UN observers, cryptographers from Fort Meade, and stone-faced men in lab coats. They set up a perimeter around Tullow, but they weren’t looking for radiation or biological weapons. They were looking for words.

The Incident at Murphy’s Hardware

It started small. Mrs. Gately, a grandmother of seven, was trying to explain to a scientist that she felt “perfectly fine.” But as she spoke the new melodic tongue—the Tullow Tongue—she reached for a word that sounded like ‘Lir-un-teth’.

As the syllable left her lips, the air in the room didn’t just vibrate; it crystallized. Every loose nail and bolt in Murphy’s Hardware rose from its bin, suspended in mid-air, forming a perfect, rotating sphere of jagged metal. When she stopped speaking out of shock, the metal fell, clattering to the floor like a thousand spilled coins.

The scientists stopped taking notes. They started taking measurements.

The Architecture of Sound

The townspeople soon realized that their new language was actually a User Interface for the Universe.