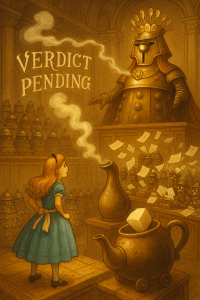

Alice in Steampunk Dalekland

Chapter One: The Clockwork Rabbit

Alice was minding her own business, which is the most dangerous occupation for a girl of her size and curiosity, because one’s own business has a wicked habit of becoming everyone else’s. She had laid out her tools upon the garden path—one honest screwdriver (which insisted it was quite respectable), a pair of tweezers (which took offense at everything), and a clockwork bird with its beak stuck slightly open as if it had been caught forever in the act of saying “Oh!” The roses wobbled about on their stems in a breeze that smelled faintly of coal and toast, and the daisies gave great, polite sneezes.

“Bless you,” said Alice, for she was a well-brought-up child, even when addressing flowers.

“Steam,” sniffed a daisy, quite dignified. “We are allergic to steam.”

“There is no steam,” said Alice, peering about. “Only sunshine and Sunday. If there were steam, I should see it, and if I saw it, I should surely say it.”

At which a discreet hiss sounded from under the azalea bush, and something somewhere went tick-tock, whirr-clank, hiss-puff!—the exact sort of reply that contradicts a person very rudely without saying a word. The roses coughed. The daisies sneezed again. Alice, being one who could not resist a noise that sounded like an argument between a kettle and a typewriter, put down the screwdriver and knelt in the flowerbed.

“I say,” she called into the dark. “Are you a mouse, a mole, or a machine?”

“None and all,” said a voice like a penny-farthing talking in its sleep. “Stand clear of the exhaust.”

Alice had just time to wonder if an exhaust was something you could trip over when the soil trembled and the bush erupted. Out burst a white blur with brass rivets, whiskers wired like telegraph lines, and a waistcoat stitched with gears that clicked themselves in a most improper fashion. It was the White Rabbit—only more so, as if someone had wound him up to a higher setting.

“You’re late!” he squeaked, and a valve near his collar let off an indignant toot. “Horribly, dreadfully, scandalously late!”

“For what?” said Alice, who did not at all like being told about her lateness, especially by a creature whose ears appeared to be tuned to the Foreign Stations.

“For the Invasion Tea, of course!” He tapped his breast, where a pocket watch had given up being merely a pocket watch and bolted itself to his ribs with a handsome row of screws. “The minutes are marching without permission! The seconds have staged a revolt! The hour has barricaded itself behind a samovar! Oh, oh!” He patted himself down as if he might find a spare minute in his pockets. “No time! Even less than that! Negative time!”

“I shouldn’t think one could have negative time,” said Alice. “It would be like owing the day a shilling.”

“Then I shall be arrested for debt!” cried the Rabbit. “Stand aside! Or rather—stand before! That is, come after me at once!” And he sprang toward the rhododendrons with such a sudden clattering that Alice felt he might disappear entirely into the arithmetic of his own legs.

“Pray wait!” Alice called, scrambling up and gathering her skirt. “What is an Invasion Tea? Do they pour the tea into the country, or the country into the tea?”

“Both, if there’s room,” said the Rabbit without turning. “But there never is.” He stamped his foot—clank, clank—and a round, brass-rimmed hatch obediently irised open in the turf, exactly where Alice was quite sure nothing had been but grass a moment before. A breath of hot, toasty air rose up, carrying with it the smell of coal-scuttles and plum jam, and also the teasing suggestion of music that had been disassembled and re-sorted by size.

“Down,” said the Rabbit, and vanished neatly into the hole like a spoon into a sugar jar.

It was not at all in Alice’s plan for the afternoon to go down a hole after a rabbit. However, plans are dreadfully bad at keeping their footing when the ground gives way. Besides, the screw-driver was looking at her as if it doubted her sense of adventure, which no respectable girl can bear. “If one can be late, one can surely be early,” she told it, “and the best way to be early is to start immediately.” She tucked the clockwork bird into her pocket (it rattled crossly), gathered up the tweezers (they pinched her for insolence), and stepped after the Rabbit.

For exactly four steps the world behaved itself. On the fifth, the turf tipped forward like a gentleman bowing too low, and Alice slid into the hatch with all the dignity she could muster in a tumble. The door clanged shut above her with the pleased decisiveness of a teapot lid.

Down she went, though “down” is entirely too simple a word for the direction she pursued. At first she slipped along a polished brass tube wide as a church aisle, with little inspection windows through which she spied unexpected things: a family of teaspoons commuting to work; a regiment of biscuits drilling in neat squares; a cloud being ironed and folded into a drawer. Presently the tube opened into a shaft whose sides were not walls at all but wheels—bright copper wheels big as dinner-tables, tinny clockwork wheels small as buttons, and serious iron wheels that turned so solemnly they might have been thinking theological thoughts.

“Oh!” Alice cried, for her heel nicked a spoke, and she had to hop most inelegantly to another spoke that came (quite kindly, she thought) to meet her. The spoke lifted her, carried her round in a delicious arc—a sort of flying without the inconvenience of wings—and set her upon a catwalk embroidered across the air like a lace ribbon.

And there were pistons: slim, chromed pistons that nodded at her like gentlemen, fat, thumping pistons that shook the air like a drum, and shivering feather-pistons that dabbed at leaks with little lace handkerchiefs. Steam fluttered from valves like sighs. Chains purred. A clock somewhere practiced scales.

“It is very industrious,” Alice remarked, which is what one says when one cannot quite say what it is at all.

“INDUSTRIOUS,” a nearby sign agreed, then flipped itself over to reveal “DANGEROUS,” then “DELICIOUS,” then “PLEASE MIND YOUR HAT.”

“I haven’t got a hat,” said Alice.

The sign, rebuked, printed “SORRY.”

As she tiptoed along the catwalk she found noble columns made of stacked teacups (a particularly Grecian order of crockery), with tea streaming through them in little brown rivers and issuing at the base into squared-off waterfalls that fell exactly to the beat of an unseen metronome. She passed a balcony where brass spiders—very polite creatures with pince-nez and tiny dusters—polished cogs and hummed, “A stitch in time saves nine, but a polish in time saves shine.”

“Do you keep this place very clean?” Alice asked one spider.

“We keep it very kept,” said the spider, which is an answer you may try at home if you wish to confuse the furniture. “And we dust the minutes on Tuesdays.”

“I hope nobody sneezes,” said Alice, thinking of the daisies.

“We have a sneeze-catcher,” said the spider, and pointed to a net strung across a corridor, in which hovered half a dozen dignified A-CH— waiting to be finished.

After a while (or possibly a before), she arrived at a crossroads with a revolving sign. “THIS WAY TO THE RABBIT,” it said helpfully, then spun itself and added, “OR POSSIBLY THAT,” then spun again and confessed, “WE ARE UNDECIDED.” The floor vibrated as if a very nervous kettle were stamping one foot. Far below, something called out, “Inspection! Inspection! All rationales to the fore!”

Alice chose the left because it looked right, and because the right looked wrong, and because she had learned that wrong and right are two sides of the same coin when the mint is in a mood. The path sloped, twisted, disagreed with itself, and finally disgorged her onto a balcony that overlooked a panorama so astonishing that—had there been any air to spare—it would have taken her breath.

Spread before her was a city of copper and comfort, of chimney-pots and impossible courtyards, of kettles the size of houses and houses the size of kettles. Little railways carried cups and saucers with the brisk efficiency of ants transporting crumbs. Over everything, like a clock that had decided to be the sky, turned a single enormous wheel whose rim was inscribed with months, its spokes labeled with days, and its hub—oh, its hub!—tick-tocked so contentedly that you felt hours would line up in good order merely to be near it.

And bustling through the streets, hissing like polite storms, came the inhabitants: Daleks, yes, but Daleks as a toy-maker might dream them after a very earnest tea. Their armor was riveted bronze; their domes wore stovepipe chimneys; monocles were strapped most seriously over their eye-stalks; their plunger-arms were fitted with sugar tongs and butter knives; and on their backs sat charming little boilers with tidy ladders and brass whistles that piped pip! whenever a notion occurred to them.

“TEA-TI-MA-TE!” boomed one from below. Another responded, “BOIL-ER-ATE!” A third, rather scholarly, proposed, “IM-PROV-ER-ATE THE SAM-O-VAR!”

“I haven’t the least idea what it means,” said Alice, “and that is precisely why I must find out.” For she was never so inquisitive as when the dictionary threw up its hands.

“Inspection! Inspection!” cried a voice just beneath her shoes. Alice looked down. There, fussing with a clipboard that was really a chalkboard that was really a harmonium, stood the White Rabbit. His ears had sprouted small weathercocks, and his whiskers traced arithmetic in the air.

“Rabbit!” Alice called, and her voice joggled a passing line of teaspoons, who complained that she’d upset their meter. “I am not late at all, you see. I am precisely when I am.”

“That’s as may be,” said the Rabbit. “But when you are is not where you are, and where you are is not why you are, and since the Why is stuck in the Other Pipe you must make do with a very small Because.” He offered her a brass token stamped BECAUSE, which she put in her pocket beside the sulky bird.

“What is the Invasion Tea?” asked Alice.

“It is the tea with which one invades,” said the Rabbit. “Or else the invasion during which one takes tea. It has not been adequately defined. That is why it is perfectly scheduled. Follow me. Mind the logic.” He hopped onto a spiral stair made of ladles and began to descend so rapidly the steps rang like bells.

Alice followed, and the stairs brought them into the street, where a polite Dalek in a velvet cravat made them a little bow. “GREET-INGS, GUEST AND CLOCK-WORK COMP-AN-ION,” it said. “MIND YOUR FEET. WE HAVE OILED THE COBBLES.” Indeed the cobbles shone like sardines, and Alice slid a little, which gave her the pleasant sense of skating through a soup tureen.

They passed the Kettle Column, which commemorated a famous boil; the Hinge Exchange, where investors traded in hinges and arguments; and the Larder District, where all the cupboards were public and the cheeses stood about gossiping in elegant rinds. At last they entered a square whose centerpiece was a samovar the size of a courthouse, with twelve gilded spouts and a judge’s bench attached to its side. Over the bench hung a banner reading: TODAY’S SPECIAL: JUSTICE WITH LEMON.

“Now,” said the Rabbit, patting his bolted watch, “we shall all be precisely on time together.” He rapped the samovar thrice with a teaspoon. At once a dozen Daleks trundled forward, each bearing a tray of scones in geometric shapes—triangles (which the scholarly Daleks approved), rhombi (which they argued about), and circles (which they regarded with suspicion, for circles had a way of going round and round the point).

A valve opened. Steam breathed. Somewhere a small orchestra tuned its teaspoons.

“BEGIN THE INVASION!” cried a Dalek in a sash embroidered with the words MASTER OF CEREMONIES AND OCCASIONAL MIS-UNDER-STANDINGS.

“BEGIN THE TEA!” cried a second, with a sash that said MINISTER OF SUGAR AND THE UNLIKELY.

“BEGIN THE REASONS!” cried the Rabbit, who had donned a little cap marked WHY (TEMPORARY).

“Do we invade first and then sip,” Alice asked cautiously, “or sip first and then invade? It is always well to know whether one is to spill a country into the cup or the cup into a country.”

The Daleks conferred, their boilers puffing thoughtful rings. At last one announced, “WE SHALL SIP THE INVASION. IT IS MORE COURTE-OUS.”

“Very well,” said Alice, feeling this was the sort of principle a person could embroider on a pillow.

A cup was offered to her by a Dalek with particularly shiny rivets. Inside the cup the tea did not merely steam; it organized itself into tiny marching squares, each square bearing a very small flag with the letter T upon it. Now and then one square would salute and fall into another, which produced a flavor like Thursdays.

Alice sipped. It tasted of toast and thunder, with a suspicion of schoolroom. “It is very brave tea,” she said.

“THANK YOU,” said the Dalek, who was clearly responsible. “WE HAVE BEEN TRAIN-ING IT.”

While they drank, a hush fell. The great wheel in the sky seemed to turn a fraction more noticeably. A breeze passed, smelling of jam and jurisprudence. The Rabbit consulted his watch so fiercely that one might have feared for its springs.

“Now,” he whispered to Alice, “you must be careful. The Great Gear is temperamental. If it feels neglected, it speeds the hours; if flattered, it slows them. And if anyone tells it a paradox, it sulks.”

“I should never dream of telling machinery a paradox,” said Alice, shocked. “They take things so literally.”

“Good,” said the Rabbit. “But do not say ‘good’ too loudly. It thinks ‘good’ is a comparative and will demand to know ‘better’ and ‘best.’”

Alice was about to say she would not say anything at all when a fanfare of kettles blared, and the Daleks parted ranks. Into the square swept a personage who was not at all a person, and yet behaved with such ceremony that even the pigeons rustled into orderly ovals on the rooftops. She was taller than the others, her casing gilded and velvet-draped, her chimney a delicate ruin of filigree, and upon her dome perched a crown of teaspoons arranged like a halo of silver commas.

“THE BOILER QUEEN,” breathed the Rabbit, bowing so low his ears indicated north and south simultaneously. “Be careful—she has the Law of Pressure on her side.”

The Queen surveyed the square with an eye-stalk that regarded things as if it had invented them and was not entirely satisfied. “CIT-IZ-ENS,” she intoned. “WE SHALL PRO-CEED BY THE LAW OF PRESS-URE: MORE PRESS-URE, MORE OR-DER, MORE SCONES.”

There were approving whistles from the boilers. Alice clapped, because it is polite to clap when a queen says anything at all, even if one does not understand it. The Queen’s eye-stalk swiveled upon her.

“SMALL BIO-LOG-IC-AL,” she said. “DO YOU AP-PROVE OF THE TASTE?”

Alice considered the question honestly. “It is very… vigorous,” she said, “but there is a trifle of soot.”

A shock ran through the assembly, as if someone had used the wrong fork at a state banquet. The Rabbit made frantic shh-shh motions with both paws.

The Queen’s chimney gave a dignified puff. “SOOT,” she repeated, very carefully, as if weighing each letter for treason. “THE LAW OF PRESS-URE DOES NOT AC-KNOW-LEDGE SOOT. THERE IS ONLY FLAV-OR OF PRO-GRESS.”

“I am certain progress is delicious,” said Alice quickly, “only sometimes it leaves crumbs.”

There was a pause with stiff elbows. Then the Queen inclined her dome by a single degree. “WE SHALL DE-TER-MINE THE TRUTH,” she declared. “PRE-PARE THE TEA TRI-BU-NAL. SUM-MON THE MAD EN-GIN-EER.”

The Daleks stirred like a hive of polite hornets. The Rabbit tugged at Alice’s sleeve. “We mustn’t stay here,” he whispered. “Trials have a way of starting with questions and ending with answers, and no one enjoys that. Come, quickly—the Great Gear is listening, and when it listens it judges, and when it judges it ticks louder.”

“But where are we going?” asked Alice, as he hustled her through a gate that had disguised itself as a pile of napkins.

“To fetch the only thing the Queen cannot overrule,” said the Rabbit, his whiskers sparking with urgency. “A Stopwatch.”

“A stopwatch cannot overrule a queen,” said Alice. “It can only time her.”

“Exactly,” said the Rabbit. “It is the Stopwatch of Sanity.”

They darted into a corridor of ladles, vanished behind a curtain woven of steam, and were swallowed at once by the humming heart of the city, where the pipes ran closer, the pistons breathed slower, and the air tasted of secrets steeped very strong.

Behind them, in the square, the kettles struck thirteen in perfect unison, which is never a good sign for a clock or a queen, and the Boiler Queen proclaimed, with tea-hot majesty, “LET THE TRI-AL BE-GIN.”

And that is how Alice, who had only meant to mend a bird, found herself—by degrees and degrees—late and early at once, with a Rabbit on one side, a Queen on the other, and the Great Gear turning above, listening for the first question.