Santa Lost in Time

Santa Lost in Time

Prologue – The Clock at the North Pole

Far, far away, in that snowy corner of the world where no postman dares deliver, there stands Santa’s workshop—a cheerful jumble of chimneys, chiming bells, and windows glowing like lanterns in the long night. Inside, elves scurried here and there like industrious beetles with pointy shoes, hammering, sawing, wrapping, and occasionally stopping for cocoa with three marshmallows (never two, never four).

In the very heart of the workshop stood an object older than Santa himself: the North Pole Clock. It was a contraption of such size and complexity that nobody, not even Santa, could tell which cog belonged to which century. Its hands were long enough to sweep a reindeer’s tail, its pendulum heavy enough to flatten a fruitcake, and its face—golden, solemn, and ever-turning—kept track not just of hours but of seasons.

On one frosty morning, just after a particularly exhausting Christmas (the year of the exploding pogo sticks, if you recall), Santa leaned upon the clock and gave it a friendly wind, as one might do to a reluctant grandfather clock.

“Just a little nudge to keep things running smoothly,” he muttered, with the weary satisfaction of one who thinks he has done a clever thing.

But the clock shuddered. It hiccupped. It gave a very impolite cough. And then, with a whirl, a wheeze, and the mournful sound of a cuckoo bird sneezing, the great hands spun round and round until the numbers blurred.

Before Santa could say “plum pudding,” the workshop, the elves, and even the snow outside dissolved into a blur of colours, and Santa was tumbled head over boots into another time entirely.

Chapter One – April Fools for Santa

When Santa opened his eyes, the snow had gone. Not melted—gone. Instead, bright green grass stretched in every direction, sprinkled with daffodils nodding their yellow heads like gossiping ladies. The air smelled not of pine and cinnamon but of damp earth and new beginnings.

Santa blinked. He rubbed his eyes. He tugged at his beard, as if to confirm it was still attached.

“By my buttons!” he exclaimed. “Where has December gone?”

He reached into his sack, which, most inconveniently, had followed him, and pulled out a present wrapped in sparkling red paper. A little boy nearby, flying a kite, looked at him curiously.

“Merry Christmas!” Santa boomed, holding out the parcel.

The boy laughed. “It’s not Christmas, silly man. It’s April!”

“April?” Santa repeated, his jolly round face wobbling like jelly. “But—but that’s months away from my proper season!”

Just then, a tall, twitchy fellow hopped out from behind a bush. He had long ears, a basket of eggs, and an expression that suggested he had been waiting centuries for this particular moment.

“Now see here, Claus,” said the Easter Bunny, tapping his paw impatiently. “This is my time. Flowers, bonnets, chocolate eggs—April belongs to me. You can’t just come clomping about in your red suit, frightening the tulips and handing out yo-yos!”

“But it isn’t my fault,” Santa protested. “The clock sneezed me here!”

The Easter Bunny sniffed. “A likely story. Next thing, you’ll be telling me you mean to dye reindeer eggs.”

Children gathered round, giggling. They weren’t afraid—Santa looked too round and red to be frightening—but they were confused. One girl asked if she could swap her Easter egg for a doll’s house. Another boy wanted both.

Santa sighed. His presents, meant for frosty December stockings, looked rather silly in the sunshine. No one wanted toy trains when there were kites to be flown, or woollen mittens when daisies begged to be picked.

And so, with cheeks redder than his suit, Santa gathered his sack and trudged off across the meadow, while the Easter Bunny muttered about calendar etiquette and the importance of seasonal boundaries.

“Ho, ho… oh, dear,” Santa sighed, scratching his snowy head. “If this is April, where shall I tumble next?”

The North Pole Clock, far away in its tower, gave another little hiccup. And the world shimmered once more…

Chapter Two – Santa’s Summer Sizzle

The world blinked. The meadow blurred. And when the colours settled back into their proper places, Santa found himself standing ankle-deep in… warm sand. Not the respectable, crunchy kind that lives in hourglasses, but the sort that sneaks into your socks and holds parliament there.

Above him lounged a sky of the laziest blue, as if it had quite given up on weather and taken to daydreaming instead. The sun beamed like a particularly boastful jam tart. A salty breeze tugged at Santa’s hat, which, being a winter hat by education and profession, had never learned the proper manners for July.

“Ho!” said Santa, trying for jolly and landing nearer to jelly. “This must be a beach.”

It was not only a beach; it was the grandest summer holiday he had ever crashed. Children shrieked happily, gulls argued about sandwiches, and a striped ice-cream cart tinkled a tune that made even the sea lick its lips. Deckchairs sat in neat rows like plump crabs at choir practice. A sign on a post declared: NO SLEIGHS ON THE SURF (which struck Santa as unnecessarily specific).

His boots made a sound like squoof with every step. He dabbed at his brow. Presently, his brow began to dab back.

“Oh, my whiskers,” he puffed, loosening his belt a notch and then thinking better of it (one must uphold standards). “December wool in July! I shall melt into a small, sticky memory.”

He untied the sack—faithful creature, it had followed again—and fished out a neat parcel. The ribbon drooped immediately, like a polite snake fainting. A small girl with sun freckles peered up from behind a moat she had built to keep out uninvited aunts.

“Merry—well—cheerful afternoon!” boomed Santa. “A gift for you.”

The girl regarded the parcel, which now looked as if it had been wrapped underwater. “Is it a bucket and spade?” she asked hopefully.

“Alas, it is a clockwork penguin who plays the piccolo.”

The girl considered this. “Can it dig?”

“It is more of a toot than a dig,” admitted Santa.

“Thank you very much,” said the girl, who had been brought up to say such things. She placed the penguin respectfully on the castle wall, where it tootled bravely until a gull, clearly a critic, tried to review it with its beak.

On the dunes above, a commotion arose. Santa looked up to see eight reindeer—summer versions of themselves, sleek and faintly bewildered—testing their hooves on the sand. The sleigh, slightly scandalised, perched atop a ridge, wondering if this counted as flying or merely very enthusiastic sitting.

“Easy, my dears!” called Santa, trudging over. “Think of it as snow that has forgotten how to be cold.”

The reindeer, who were better philosophers than most, tried a tentative slide. The sleigh, grasping the spirit of the thing, swooped down the dune with a whoop and skimmed across the firm sand near the water’s edge. Children squealed. A lifeguard stood and shaded his eyes.

“No sleighs on the—well, near the surf!” he cried, consulting the sign and then the horizon, as if reinforcements might be arriving by whale.

“I’ll be careful!” Santa promised, which is what everybody says to a lifeguard when they intend to be delighted.

An elderly couple strolled past, pausing to admire the spectacle.

“That gentleman is terribly overdressed,” said the lady.

“It is the fashion in the North,” the gentleman replied gravely. “They never quite got over winter there.”

Meanwhile, three elves who had managed to cling to the back of the sleigh during the clock’s recent hiccup tumbled out onto the sand like tidily packed laundry. They were Workshop Elves of the Old School—aprons, pencil stubs, a general air of cheerful engineering. Spotting the glittering surf, their eyes widened.

“Boards!” cried the first, whose name was Rivet.

“We must wax them!” cried the second, who answered to Tweak.

“For optimum gliding!” added the third, Nobble, who kept a notebook for recording all optimums.

Unfortunately the only boards available were the wooden signs that said things like PLEASE MIND THE TIDES and NO DOGS AFTER TEA. The elves waxed them until they gleamed like toffee apples, then attempted to surf. They shot forward magnificently for precisely the length of a surprised squeal, at which point the boards decided they preferred being notices and lay down to read themselves. The elves skimmed into a polite wave and emerged decorated in seaweed like lords at a very green coronation.

Back by the sleigh, Santa attempted to distribute a few seasonal delights. Candy canes, when introduced to July, become theoretical objects: they exist chiefly as the idea of stickiness. His sack produced them in drifts; they wilted into red-and-white ribbons that children used quite happily to stripe their sandcastles. A toy drum filled itself with sand and developed a tone of such solemn dignity that a small procession formed—two toddlers, one dog, and the clockwork penguin—to march in circles and hum.

“Perhaps,” Santa muttered, mopping, “perhaps I should adapt.”

He rummaged in the sack with both arms (a rummage of consequence) and brought forth… a parasol. A very large parasol. The sort, indeed, that might have been lent by a sympathetic cloud. He planted it in the sand with a thunk, and shade pooled outward like cooled chocolate. People cheered. The ice-cream vendor doffed his paper hat and wheeled closer.

“You’re a marvel, sir!” he declared. “Would you care to try our newest flavour—Thunder & Plum?”

“I ought not,” said Santa, already licking. “It would be unprofessional to—mmm—favourite one—oh my stars—above another.”

The vendor leaned confidentially over the counter. “If you’re the chap from Christmas—and between ourselves, you look outbreakingly like him—could you conjure a breeze? Only the heat’s got the gulls bold and the sun has gone quite indecorous.”

Santa brightened. “A breeze! Why, I have just the thing.” He produced from the sack a pair of Grandmother’s Bellows (north-polar issue), ordinarily employed to coax fire into singing. He squeezed them gently. A polite draught stepped out and shook hands with everyone. He squeezed again. The draught upgraded to a decent breeze, which ruffled umbrellas, put ambition into kites, and persuaded even the jam-tart of a sun to keep a modest distance.

“Splendid!” cried the vendor. “You are a treasure.”

Santa bowed, which in his case is a small avalanche with manners.

Yet even with breezes and parasols and parasol-shaped shadows, a problem persisted: presents. The beach wanted balls, buckets, and the infinite supply of towels that all beaches demand and none possess. Santa tried his best. He coaxed the sack to consider a temporary curriculum change. Presently it obliged: out came a fleet of inflatable rings (striped like serpents from a circus), a kite that drew pictures in the sky (mostly of sandwiches), and a set of skipping ropes that, being ambitious, taught themselves to count in three languages.

The afternoon danced on. The sleigh became a dune-to-shore shuttle for children squealing with the sort of joy that makes adults remember how to be small. The lifeguard relaxed into the extraordinary and lent Santa his whistle, which Santa blew with judicious kindness whenever a gull looked like applying for a taste of everything.

And yet—between the laughter and the lemonade—Santa felt a little wobble in his cheer. He was doing good work (summer work, splendid work), but it was not his work. He missed the blue hush of winter evenings; the satisfying hush before chimneys; the way the stars in December kept their appointments like punctual diamonds.

He sat upon the sleigh runner as the sun leaned toward tea-time and watched the tide sweep its silver broom along the shore. Beside him perched the lead reindeer, whose nose had acquired a dab of suncream in the general excitement. Together they considered the horizon.

“I am a visitor here,” Santa said softly. “A happy one, but a visitor all the same.”

The reindeer nodded in the manner of one who understands seasons by hoof and wind.

Far away—so far that even gulls could not gossip about it—the North Pole Clock gave a thoughtful hmm. Its great hands, which keep no secrets from fate, twitched. Sand blurred. Parasol shadows folded like fans. The world tilted very slightly, as if to peer round a corner.

“Hold tight,” Santa told everything, which is good advice in any case.

The beach, the bells, the lazy jam-tart sun dissolved into the smell of leaf-smoke and cider. Santa felt the sand become soil under his boots. A pumpkin rolled past with a look of October about it.

And with that, he tumbled headfirst into the next mistake in the calendar.

Chapter Three – The Autumn Troubles

The sand slipped away, like sugar dissolving in tea, and Santa found himself standing among fields the colour of toasted bread. A crisp wind fluttered his beard. Leaves, red as jam and gold as butter, skittered across the ground as though late for some very important appointment.

“October,” Santa muttered, peering at the hedgerows heavy with blackberries. “Well, at least it’s cooler than July.”

He plodded forward, boots crunching, until he stumbled into the middle of a pumpkin patch. And what a patch it was! Enormous globes sprawled across the earth, fat and round and smug about it. One of them rolled against Santa’s shin, as if to say, Kindly carve me, sir.

“Ho-ho! A fine orange Christmas bauble you would make,” Santa chuckled, patting its side.

But before he could fetch out his penknife, a gaggle of children in cloaks and masks came rushing through the field. A witch, a skeleton, and a pirate all halted at the sight of him.

“It’s Father Christmas!” cried the skeleton, who clearly needed spectacles.

“No, it’s just a fellow in costume,” said the witch, eyeing Santa’s red suit suspiciously. “You don’t get Christmas in October.”

Santa held out a wrapped parcel, his natural instinct. “Merry—well, Happy—whatever this is!”

The pirate frowned. “We don’t want presents. We want sweets!”

And at once, the whole pack began chanting: “Trick or treat! Trick or treat!”

Santa glanced down at his sack. It produced a toy train, a woollen scarf, and a clockwork angel that insisted on singing carols in the wrong season. Not a jelly bean in sight. The children groaned.

Just then, a lantern glowed on the fencepost—a pumpkin, freshly carved. But instead of a jagged, frightening grin, it wore a jolly, round smile, very much like Santa’s own.

“Ho!” Santa cried. “Now that is a pumpkin with proper cheer!”

The children, however, were unimpressed. “It’s supposed to be scary,” one explained. “That pumpkin looks like it wants to hug us.”

“Well, what’s wrong with hugs?” Santa asked.

“Nothing,” said the skeleton slowly. “But it doesn’t give anyone a fright.”

Before Santa could argue further, a crow on the scarecrow’s hat gave a loud caw. The sky darkened. The wind blew harder, scattering leaves into wild dances. The pumpkins themselves seemed to chuckle, deep and earthy.

And there, at the edge of the field, stood a figure cloaked in russet robes—the Guardian of Autumn. He raised a staff tipped with a branch of oak, and the leaves swirled obediently around him.

“Santa Claus,” the Guardian said, in a voice like the rustle of corn husks. “Why do you meddle in my season with gifts and baubles? You confuse the children, and you confuse the pumpkins most of all.”

Santa swallowed. “It wasn’t intentional, sir. The North Pole Clock has gone awry, and I find myself lost in time. I only meant to spread a little cheer.”

The Guardian’s eyes softened, though they were sharp as cider. “Cheer has its place. But each season carries its own lessons. Autumn teaches us to give thanks, to share the harvest, to prepare for the dark.”

Santa nodded gravely. He knew he had much to learn before he could return home. And even as he pondered this, the leaves began to stir once more, as if the world itself was turning another page…

Chapter Four – Santa Meets the Keepers of Time

The pumpkins, the children, and even the scarecrow’s crow folded away like pages turned by invisible fingers. Santa blinked, and when he opened his eyes he was standing in a place unlike any other he had ever seen.

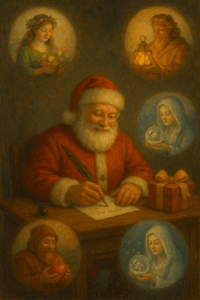

It was not a room, nor a field, nor even a proper sky, but something between them all. Above him hung constellations that looked suspiciously like clocks, their stars ticking in silver rhythm. Beneath his boots lay a great circular floor, carved with patterns of leaves, snowflakes, raindrops, and rays of sun, all turning slowly as if the world were a grand music box.

And standing at the four edges of this place were the Guardians of the Seasons.

To the east stood Spring, clad in robes of the softest green, a crown of daffodils upon her head and a songbird perched upon her shoulder. Her eyes sparkled like dew on a spider’s web.

To the south stood Summer, golden and tall, his hair a blaze of sunlight, his cloak the colour of ripened wheat. Sparks of warmth leapt from his fingertips and drifted into the air like lazy fireflies.

To the west stood Autumn, broad-shouldered and russet-robed, carrying a staff of oak and acorns. His beard was the colour of cider, and his eyes glowed like embers in a hearth.

And to the north stood Winter, pale and serene, wrapped in white furs and silver lace. Her breath came out in delicate snowflakes, her crown glittered with icicles, and her eyes were clear as frozen ponds.

Together, the four spoke in voices that blended like wind through the seasons:

“Santa Claus, keeper of Christmas, why do you trespass upon our times?”

Santa, who had been in scrapes before (chimneys are nothing if not scrapes), bowed deeply. “Most honoured Guardians, I did not mean to intrude. The North Pole Clock sneezed me into your months, and I have been tumbling from one season to another ever since.”

Spring tilted her head. “The clock is old. But it does not sneeze without cause.”

Summer frowned. “Perhaps you wound it too tightly.”

Autumn rumbled, “Or perhaps you forgot that each season must keep its own place.”

Winter’s voice, cold but kind, drifted like frost over glass. “You must learn, Claus, that time is not yours to command. Yet… we see in you no malice, only muddle.”

Santa’s cheeks grew pinker than usual. “I only wished to keep things running smoothly. To make sure the cheer of Christmas would never falter.”

“Cheer,” said Autumn, “is not the same as balance.”

“Indeed,” said Spring. “Every season has its own gifts—seeds, sunlight, harvest, snow.”

“And you,” said Summer, “must prove you understand this truth before you may return to your December.”

The Guardians raised their hands together. The constellations above whirled, the patterned floor spun, and Santa felt a gentle tug, as though the very months were leaning forward to watch him.

Winter spoke the verdict:

“You must face the Trial of the Seasons. One task for each of us. Complete them with care, and you may return to Christmas Eve. Fail… and you shall wander through misplaced months forever.”

Santa gulped, his beard trembling. He did not fear chimney smoke nor icy roofs, but the thought of disappointing children—ah, that chilled him deeper than any winter wind.

He straightened, tugged at his coat, and gave a bow that shook his belt buckle like a bell.

“Then set me to my tasks, noble Guardians. For I shall not rest until I am home in my December, sack in hand, reindeer at the ready.”

And the Guardians of the Seasons, grave and shining, nodded as the air filled with the scent of blossoms, the heat of fire, the drift of leaves, and the hush of snow.