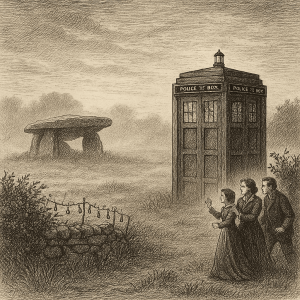

Doctor Who and the Music of Haroldstown Dolmen

Doctor Who: The Music of the Dolmen

A lonely Irish field. An ancient stone table the locals dare not cross after dusk. And music,sweet, wordless, and terrible,drifting over the hedgerows at twilight.

When the TARDIS sets down near Haroldstown Dolmen in nineteenth-century County Carlow, the Doctor dismisses it as a simple megalith. But the parish books tell another story: of vanished boys and broken fiddle-bows left upon the stone; of a lady in green velvet singing the living down into silence. Investigating beneath the dolmen, the Doctor discovers a chamber of whispering figures, neither alive nor dead, while the song coils tighter around his companions.

What lies under the stone is no tomb, but a trap still feeding. To save Ian, Barbara and Susan from the music’s call, the Doctor must confront the intelligence that plays human souls like strings… before the last note falls.

Contents

- A Harp in the Hedgerows – In which the travellers meet a worried historian, a superstitious farmer, and a song that is not a song.

- Parish Ink and Green Velvet – Testimonies, tokens on stone, and a vision upon the capstone that nearly claims Ian.

- What the Earth Remembered – The Doctor digs; a lantern shows too much; Susan hears her name from beneath.

- The Unplayed Note – A bargain, a breaking, and a silence that does not quite hold.

Chapter One: A Harp in the Hedgerows

The Irish countryside was the colour of old coins as the day ran down, bronze light on barley heads, silver along the backs of the leaves, and here and there a small splash of green where the hedges came close to the lane. The cry of a corncrake, monotonous yet oddly companionable, rose and fell from the meadow beyond. A rook settled on a low stone wall and watched, head cocked, as the blue box made its customary complaint against the fabric of the world and came to rest with a wheeze and a thump.

Within, the central column slowed, sighed, and stopped. The Doctor, who had been hovering over the controls with the air of a conductor bringing off a difficult passage, straightened and adjusted his lapels with an expression of satisfaction.

“There we are, hmm? There we are,” he said. “A most curious resonance indeed, my dears. I have not heard its like since, well, never you mind since when. Ireland. Leinster. Mid-nineteenth century by the smell of the ink they use here.” He sniffed the air with relish, as if time itself exhaled different perfumes in different decades.

Ian, bracing himself against the rail, exchanged a glance with Barbara. “Did you say resonance, Doctor?”

“I did, Mr Chesterton,” said the Doctor, his eyes bright and mischievous. “A flutter in the subsonic band, close to the ground. Something is, ah, playing this bit of countryside, if you follow me.”

Barbara laughed lightly. “In Ireland, that could mean only one thing: a fiddler behind a hedge.”

The Doctor’s expression tightened a fraction. “Mmm. Let us hope so.”

Susan had already fetched her cardigan from a peg. “Oh, Grandfather, it sounds lovely. Can we go and see?”

“Caution, child, caution,” the Doctor said, though his hand was already on the door lever. “We shall proceed carefully. No dashing about.”

The doors opened on air that smelled of nettles and warm dust. The lane ran between low walls, and beyond the right-hand wall a tilled field lay open to the declining light. In its centre stood the dolmen: a great dark slab balanced upon uprights, like a table set for giants who had forgotten to return to their meal. It cast a long rectangle of shadow.

Barbara drew in her breath. “How extraordinary! A cromlech, Doctor, look at the supports. So many of them still standing.”

“Yes, yes,” the Doctor murmured, shading his eyes with a hand. “I see, I see. The cairn long gone, the skeleton of the thing left to sulk in the field. Mmm.” He tapped the wall with his cane. “And if the country tales are anything like those of Brittany or Wales, the locals will not pass that spot after dark without crossing themselves first.”

“They’ll cross themselves in daylight too, if they’re sensible,” came a voice from the lane’s bend.

A man stood there, not young, with a neat beard and spectacles that caught the light. He carried a satchel that might have belonged to a parish clerk and had the faintly ink-stained fingers of someone at home among papers.

“Forgive me,” he said, doffing his hat. “I did not mean to eavesdrop. You were admiring the ‘giant’s table.’ We call it Haroldstown Dolmen. Patrick Kavanagh, no relation to the poet, alas. I keep a few records for the parish and for my own sins.”

The Doctor’s manner, which could be forbidding to strangers, softened a whisker. “Records, sir? Then perhaps you can tell me what the stone has been saying of late.”

Kavanagh’s polite smile flickered. “You have heard it too?”

Susan looked up sharply. “Heard… what?”

Kavanagh glanced at the field, then back at the travellers, weighing them. “Come down to the town,” he said at last. “There’s a pot of tea and a ledger that might interest you, if you’re not pressed for time.”

“Pressed for time,” the Doctor repeated, amused. “My dear sir, time presses me, but I do not always press back. Lead on.”

Kavanagh’s rooms above the stationer’s had a genteel, worn order: shelves of pamphlets, bundles of parish books tied with ribbon, a map of the county on the wall with pins marking rivers and ruins. Susan stood at the window and watched the last glare of evening leave the rooftops, while Ian and Barbara crowded at the table where Kavanagh had opened a ledger.

“Vol. iii, folio twenty-seven,” he said, tapping a neat line entered in an older hand. “‘June the Fourth, in the Year of Our Lord 1796. Patrick Byrne, son to Michael Byrne, labourer, did not return to his house after eventide. Last seen in the field of the great stones. Cap discovered upon the monument at a height no man might reach unaided.’” Kavanagh closed the book gently, as if not to wake what slept between its pages. “There are other entries. A herdsman in ’23. A travelling fiddler in ’39. Tokens left on the stone, and no bodies.”

Barbara’s fingers had laced together. “Local superstition would have it… fairies?”

“Some say,” Kavanagh allowed. “But my grandfather swore he once heard music out there—harp music—when he was a boy. Came home white as paper. Wouldn’t walk that road at dusk again in his life.”

Ian aimlessly polished the rim of his cup with a thumb. “If it is some trick, Doctor, we might catch the fellow at it!”

“Fellow?” Kavanagh repeated, with a flicker of discomfort. “Sir, forgive me, but if it is a who, we’ve never laid a hand on him. It comes and goes like a draught. And there’s this.”

From the satchel he drew a small bundle wrapped in linen. He unrolled it and placed upon the table an object no larger than a hand: a little figure, crudely fashioned, its arms drawn up as if to shield itself, its face contorted in a fear made somehow more terrible by the coarseness of the moulding.

Barbara recoiled. “Where did you?”

“Ploughed up near the dolmen by Keating that owns the field. He threw it away at once and told no one. His wife found it and brought it to church. She said it had the look of a neighbour who went missing when she was a girl.” Kavanagh hesitated, then added, “Sometimes at night, I would swear it… sighs.”

Ian made a sceptical sound, but it died quickly. The figure seemed to bring with it a small, stale cold, a breath from a place it had no right to recall.

The Doctor had not sat down. He stood a little apart, cane in both hands, head lowered, eyes bright under the white sweep of his hair. When he spoke, it was as if answering himself.

“Something that eats by ear. Mmm. A lure in sweet clothing to draw the curious. A chamber to keep what it catches, close and compressed, like the wax cylinder in a phonograph. Play it back, and you get a little of your.” He broke off sharply and turned the full beam of his attention upon Kavanagh. “You will not go out there at night, sir. Not for any reason at all.”

Kavanagh attempted a smile. “I am not brave, Doctor.”

“That,” said the Doctor, rather kindly, “is a virtue in this case.”

They reached the lane at the falling of full dusk. The hedges were shadows now, the white of dog-rose blooms like smears of pale fire. The dolmen crouched in its field, black against a sky that still held a little greenish light toward the west.

“Doctor,” said Ian, “if this is wise.”

“Wisdom and inquiry do not always sit on the same bench, Mr Chesterton,” the Doctor said crisply. “Barbara, Susan,close to me, if you please. If you hear music, you will not go toward it.”

Susan nodded, grave, slipping a hand into Barbara’s. “Yes, Grandfather.”

They went through the gate. The field had that breathless stillness that sometimes falls upon the countryside at the end of a very long day: a pause where even the insects seem to hold their tongues, as if waiting to see what the sky will decide. The dolmen’s shadow lay like a door.

The first note came as a tremor, almost felt in the ribs, as much as heard: a bright, cold tone that was not entirely natural, yet promised all the sweetness the human ear ever craved. Then another, answering it, and after that the weaving of a melody that had no words and no mercy.

Ian’s hand slackened in Barbara’s. “It’s… beautiful,” he said, and took a step forward.

Barbara jerked him back. “Ian, no!”

The song turned then, as if noticing them; it curved like a hand around the heart and pressed. Susan made a small, frightened sound. “Barbara, she’s there, she’s there!”

The woman upon the capstone reclined in careless grace, her hair a sheet of copper in the last of the light, her gown darkly green. Her lips moved, and the song seemed to pour from the air around her rather than from her mouth. Beside the dolmen, on a plain wooden chair whose legs had sunk too deeply into the earth, sat a thin man with a face the colour of candle-wax. His fingers went back and forth upon the strings of a harp whose notes fell like frost.

The woman’s eyes opened. They were the colour of shallow water where it runs over glassy stones.

“Every ear that hears our song is chosen,” she said softly. “We need one more voice.”

Ian leaned forward again. The Doctor brought his cane down sharply on the ground like a gavel.

“That will do,” he snapped. “We are neither choir nor congregation, madam. You will cease.”

For an instant the woman’s expression altered, as if something behind her eyes had turned its face. The harpist’s hand faltered upon a string. The Doctor’s cane flashed; he flicked some small silver thing toward the dolmen, and the air cracked with a thin discordant squeal.

The glamour unraveled like silk cut with a knife. The woman was not there. The chair was not there. The harp’s last note hung too long, then skated into silence.

Barbara, breathing hard, realised her cheeks were wet. She did not remember beginning to cry.

Ian stood rigid, his jaw set, as if he had dragged himself back to shore from a very long way out. “Thank you,” he said, not looking at the Doctor.

“Indeed,” the Doctor muttered, re-capping the device. “If one is to carry a tuning fork, one may as well bring it in the right key. Back, all of you. That is quite enough for this evening.”

“But Grandfather,” Susan whispered, unable to look away from the stone, “what is she?”

The Doctor did not answer until the gate was shut behind them and the lane lay between them and the field.

“Not she, child,” he said at last, very gently. “It.”

Kavanagh had gone to his bed by the time they reached the town, so they saw him the next morning, pale and red-eyed, with the stubborn look of a man who has not slept and resents his wakefulness.

“I dreamed the air was full of dust,” he said by way of greeting. “Not the good dust of a shop,ash, perhaps. And in it a whispering that was almost.” He stopped. “I hope you have better news than I have dreams.”

The Doctor’s fingers were thrumming on the head of his cane, impatiently pleased with the progress of his thoughts. “News? Hah! We have a hypothesis. Your dolmen is not merely a memorial to old bones, sir. It is the bared skeleton of a device,primitive in appearance, but not in purpose. Long ago something learned that human vitality may be drawn, coaxed free by beauty, by longing, by a promise placed in the ear. It set a stage, put on a face,green velvet and red hair,and waited. The chamber below is where it keeps what it takes.”

Kavanagh’s knuckles whitened upon the back of the chair. “You mean to go under it?”

“I mean,” said the Doctor, relishing the shock of the words, “to look.” He wagged the cane. “Not you. Not you, my dear Barbara, nor you, Mr Chesterton, nor certainly you, child. I shall make my own examination, and I shall go in daylight, when the thing prefers to do its business. Hah! We shall see what the earth remembers.”

Susan bit her lip. “Grandfather…”

“Hmm?” The Doctor looked up, softer at once at the tone.

“What if it tries to sing to you?”

The Doctor laid a hand for a moment on her shoulder. “Then I shall be very rude and put my fingers in my ears. It is a talent that increases with age.”

He smiled; and for all the lines of pride and obstinacy in his face, there was kindness enough in that smile to steady them.

By noon, the sun was brass upon the hedges, and heat made ripples over the dark soil. Keating, the farmer, grudgingly let them through the gate, muttering in a low, angry way about spades and strangers and bad luck carried home on boot-leather. He stood, arms folded, to watch. The Doctor, who could match a farmer for stubbornness any day of the week, paid him no mind. He had brought only a small hand-spade and a lantern, and his movements were precise and fussy, like a man trimming a wick.

“Chesterton,” he said, without looking up, “if I so much as say ‘back,’ you will take Miss Wright and your pupil beyond the gate. Do you understand?”

Ian, who understood better than the Doctor’s casual tone suggested, said, “I do.”

The Doctor’s spade rang softly against something that was not earth. “Ah!” He cleared the soil away with his fingers and exposed the edge of a flat stone: a paving, not an accident, fitted, set.

“Help me ease it up,” he said, and the two men shifted it a fraction, just enough to make a mouth for the darkness. The Doctor lit the lantern and held it over the gap.

The breath that rose from below was cold, though the day was hot. It smelled like cellars and eclipses.

At first Barbara saw only the rough lining of the chamber, small stones jammed together by hands that had not cared to make them beautiful. Then the lantern flame steadied, and she followed its light downward and saw the first of the figures.

A child’s toy, one might have said, but no child would have chosen to play with it: a little body folded in upon itself, arms up as if to ward off a blow, the mouth pulled into the narrow O of someone trying not to cry out. Another beside it, and another, arranged without order, as if they had been poured there. A dozen. Two dozen. More. And in the seeing of them, there was a sense of number beyond counting, a hint that the chamber went down and down in shelves like those in a library nobody visited anymore.

Barbara’s hand had gone to her throat. She did not know she was making a small sound until Ian’s fingers closed around hers. The Doctor, who had made no sound at all, leaned a fraction lower. His eyes were dark blue, almost black in the lantern-light.

“One expects bones,” he said, very softly. “But the dead do not crouch.”

Something moved. The small head of the uppermost figure turned, very slightly, like a flower seeking a warmer patch of sun. Its mouth opened. The sound that came was not a word, not in any language of the room above, but the meaning of it came all the same: a long, low, patient sorrow.

Another turned. Another. The whispering rose,never loud, never strident, that would have been easier to resist—but insistent, like a draught under a door that will not quite shut. It trickled into the ear whether one would have it or no. There was nothing pretty in it; and yet Barbara felt, horribly, the wish to follow the sound down, to make herself small enough to fit, to fold up and join them and be finished with deciding anything ever again.

“Back,” said the Doctor, in a voice that had no tremor in it at all. “Back, all of you.”

They stepped as if through treacle. The Doctor set the lantern aside on the ground and reached for the edge of the slab. Ian caught the other side. Between them they let it fall.

It fell with a noise like a hand clapped over a mouth. The whispering ceased. The light, bouncing, sent a last mad trapezoid across the dolmen’s shadow and then steadied.

Keating swore under his breath and made the sign of the cross.

The Doctor stood, breathing rather fast now. He took out a handkerchief and mopped his forehead, then his hands, as if the sound had left some residue upon the skin. He regarded the dolmen a moment longer, as one regards a chessboard on which one has just seen a gambit revealed at last.

“Enough,” he said. “We have seen all we need for one day. Come away.”

They went back through the gate. From the lane, the dolmen looked very innocent again, and the field very like all Irish fields at noon: a place for haycocks and cartwheels, laughter and the long work of living. The knowledge of the thing below made the day feel hollow, like a church bell whose tone one cannot hear without imagining the spider in the cup.

In Kavanagh’s rooms, the Doctor said nothing for some time. He stood by the window and watched the light slide toward afternoon. The little clay figure lay upon the table upon its linen; no one had touched it since morning.

At last he turned. “My dears,” he said. “We are dealing with a parasite that recites its liturgy in music. It requires answerers. It has, for centuries, had all it needs.”

“And what do we require?” Barbara asked, very tired, very steady.

The Doctor’s face was kind, and quite without mercy. “To refuse the chorus,” he said. “And to teach others to do the same.”

Outside, a cart went by, wheels creaking, a boy whistling a tune that had no business sounding so like the shape of the whisper they had just heard. The Doctor’s hand tightened on the head of his cane until his knuckles went white. Then he relaxed them and smiled.

“Courage, my dear,” he said quietly to Susan, who was staring at nothing. “We shall see this through.”

The afternoon deepened. Somewhere in the town a church bell tolled the hour; in the fields beyond, unseen, the dolmen waited for the cool of evening and the first note.

End of Chapter One.

Chapter Two: Parish Ink and Green Velvet

Morning laid a pale sheet over Tullow, as if the town had slept badly and would thank you not to raise your voice. A milk cart rattled, the bell in the market hall coughed itself awake, and in Mr Kavanagh’s rooms the kettle performed its modest miracles.

Barbara arranged cups with schoolroom precision. Susan stood at the window, watching a cat edge along a wall with the solemn care of a tightrope walker. Ian scribbled a list on a scrap of paper, lips moving as he itemised names.

“The farmer’s wife,” he said. “Mrs Ryan at the butter stall. The curate, for the locked presses. And a Mullins who keeps a shop by the quay. Kavanagh says his grandfather was the vanished fiddler.”

“Quite right, quite right,” murmured the Doctor, buttering a slice of bread as if it were an experiment. “We shall divide and proceed carefully. Mr Chesterton and Miss Wright will attend to the parish ink. Miss Susan will remain here with Mr Kavanagh.”

Susan’s face fell. “Grandfather…”

“You are marked by what we heard last night,” the Doctor said, gentle but immovable. “No field for you until I can make a better nuisance of myself than the thing under the stone. Besides, you will be useful here.” He patted her hand. “Listen for anything odd, and if you hear even a pretty note, you will sing ‘Greensleeves’ at the top of your lungs.”

“That will alarm the neighbours,” said Kavanagh, attempting a smile.

“Excellent,” said the Doctor, quite pleased. “Neighbours are notoriously hard to alarm in time.”

They set out. The town went about its business with that stubborn ordinariness that sometimes offends a troubled mind. Yet here and there, behind shutters and under lids, a certain caution peeped out and withdrew.

Barbara took the butter stall first. Mrs Ryan ruled her small domain with a practised hand and an unflustered eye. At the mention of the dolmen her mouth tightened, but she did not refuse speech.

“I saw her once,” she said, squaring a pat with the wire. “I was no taller than this counter. Red hair like a fox’s brush, gown green as a moss-bank after rain. She lay upon the big stone and sang without words. And the worse of it was that you wanted to go to her. Even while your arms prickled and your toes dug into your shoes, you wanted to go.”

“The man with the harp?” Barbara asked.

Mrs Ryan’s knife stopped a heartbeat, then went on. “Thin as a famine and pale as tallow. I will tell you a thing I have never told a soul. He seemed not quite… here. As if he were stitched to the edge of the world and might slip off if you breathed on him. I went home another way that day and would not pass that field for a year.”

Barbara thanked her. She left with a small cheese pressed into her hand and the sensation of having been warned, kindly and thoroughly, by someone who knew the cost of being wrong.

Ian and Kavanagh secured the curate’s permission to unlock the presses. The young clergyman tried to joke the dust away, then surrendered his cheerfulness and handed over the key with a little sigh.

They laid out volumes in a neat procession: copperplate names, spidery notes, blots where someone’s hand had shaken. Ian traced three entries with a finger. The labourer’s boy in 1796, a herdsman in 1823, the travelling fiddler in 1839. Each with the same detail. Tokens on the stone. No body returned.

“If I could preach a sermon that would stop them walking that lane at dusk,” the curate said, almost to himself, “I should. But you cannot very well forbid a field, can you, Mr Chesterton? It sounds like superstition from the pulpit, and the young laugh, and then they go to prove me wrong.”

“We shall try to prove you right,” Ian said, closing the book with care.

They left the church and went on to Mullins’s shop. A bell jangled over the door. Twine, lamp oil, peppermint, and paper: the smells of small, steady business. Behind the counter hung a frame, and in the frame a fiddle-bow, snapped clean near the frog.

“My grandfather,” Mullins said, when asked. He had the deliberate voice of a man who disliked to waste words. “He went out one evening and came back as wind. They found that bow on the stone. We hung it there so it would not vanish twice.” He looked at Ian without challenge or invitation. “If there is a trick, I have not found it.”

Ian could only nod.

Meanwhile, the Doctor terrorised Tullow’s more obliging tradesmen. He emerged from a watchmaker with a cracked tuning fork, from a toy-seller with a cheap harmonica, from a tinsmith with a lattice of wire, and from a grocer with a length of twine and a handful of small bells.

In Kavanagh’s yard he strung the wire between uprights and made the bells sulk and the harmonica reeds complain.

“We are not making music,” he explained to Susan and their host, face alight. “We are making the opposite. Draughts under doors, snags in the thread. If the air vibrates in that particular pattern, the glamour finds it hard to keep its hem straight.”

“Grandfather,” Susan said in a small voice, “I woke humming the tune.”

The Doctor’s expression softened to something very white and steady. “Did you choose to hum it?”

“No,” she said, embarrassed. “It was there when I woke, like the taste of something I ate in a dream.”

“Then we shall untaste it,” he said, and kissed her hair in a rare concession to tenderness. “If you hear it again, you know what to sing back.”

She laughed despite herself. “Greensleeves.”

“Quite right. It has driven greater monarchs than me to distraction.”

He touched the fork to his contraption. A thin, tooth-aching whine set the bells shivering. Even Kavanagh winced.

“Splendid,” said the Doctor, beaming. “If we hate it, so will it.”

They met at the field well before dusk. Keating guarded his gate with folded arms and a scowl that tried to pass for indifference. The Doctor nodded to him as if asking to borrow a spade were a matter of lending a teaspoon.

“We have added a little wire to your hedge,” he said cheerfully. “A kindness to singers who need practice.”

Keating’s eyes narrowed at the glitter among the brambles, but he said nothing. In Ireland a man may tolerate oddities if the oddity looks like it knows its own mind.

They went in. The dolmen waited, square and black and innocent as a chair in a dark room. The Doctor placed his improvised device against the field wall and adjusted a screw with the air of a man tuning a harpsichord he privately despised.

“Positions,” he said. “We keep our heads and our distance. If it speaks to you, do not answer.”

The light thinned. The hedge gave a little complaining buzz as a breeze found the wire. A lark went abruptly silent.

The first note came. The wire shivered and made the small bells fuss. The tune tried the air, slipped, corrected itself with a nasty grace, and pressed on.

Susan’s hand found Barbara’s. “It is here,” she whispered.

The woman in green velvet lay upon the capstone as before, perfect, impossible, inevitable. The harpist sat beside the dolmen, chair sunk deeper, pale hands moving over strings that were not quite strings. The song flowed like water over glass.

“Every ear that hears our song is chosen,” the woman said. “We need one more voice.”

Her eyes opened and found Ian. The melody bent itself toward him. Barbara felt it change its shape, cunning and gentle, promising exactly the comfort Ian would never have thought to ask.

“Ian,” she said, very quietly, as one addresses a boy at the brink of mischief in a laboratory. “If you take another step, I will be personally offended.”

He startled and blinked. The moment cracked. The Doctor snapped the fork and fed more sourness into the wire. The glamour wavered, recovered, reached again.

Then, from beside Barbara, a stubborn, off-key “Greensleeves” began. Susan, white-faced, sang in the deliberate, uncompromising tones of a girl choosing to be clumsy in order to be safe.

The woman in green turned her gaze on the child. There was nothing sweet in it now.

The harpist struck a single icy note. The chair sank another inch.

“Enough,” said the Doctor, stepping forward, cane lifted like a conductor’s baton. “You shall not have her.”

The field pressed tight around them for a heartbeat, as if the very hedges had leaned in. The Doctor tipped his device a fraction. The wire screamed, the bells rattled wrong, the harmonica reeds made a noise like a saw catching.

The glamour folded itself away like a shawl. The capstone lay bare. The air tasted metallic, as if a coin had been held too long on the tongue.

Ian released a breath he had not known he was holding. Barbara’s fingers ached. Susan’s song dwindled into a little hiccup and stopped.

Keating at the gate crossed himself without comment.

The Doctor’s hands trembled once, then steadied. “It aims,” he said to no one in particular. “It learns its marks and plays them separately. Well. We can learn too.”

He gathered up his contraption with the brisk tenderness of a man packing away a fussy instrument, and they retreated to the lane.

“Not at dusk again,” he told them as they walked. “That is its hour. Tomorrow we go in the plainest daylight. If it insists upon a performance, we shall insist upon our terms.”

“Terms?” Ian said, wary.

The Doctor’s eyes were very bright and quite unreadable. “Everything that feeds understands a bargain,” he said softly. “I do not propose to keep one, but I may propose one.”

Back in Kavanagh’s rooms, the Doctor spread wire and notes and forks and bells upon the table with a magician’s self-importance and a chemist’s economy. He scribbled a few figures, frowned, and struck them out.

“We must take away its harmonics,” he muttered. “Starve the glamour of its neat edges. Then, if it must sing, it will sing raggedly.”

Kavanagh looked from the device to the man with the tuning fork. “Doctor,” he said, voice almost steady, “what if it asks for me?”

The Doctor’s expression altered, sudden and kind. “Then I shall be extremely rude on your behalf, Mr Kavanagh.”

He turned to Susan, who had been very quiet. “You were brave,” he said. “Tomorrow you will be braver in a different way, by staying behind these walls until I call.”

She nodded. “Yes, Grandfather.”

Night slid over the rooftops. Somewhere a dog barked, was hushed, and barked again. In the field beyond the hedges the dolmen rested, and under it, in the chamber lined with scratched stone, something that had learned to whisper waited and listened and did not sleep.

To be continued in Chapter Three: What the Earth Remembered.

Chapter Three: What the Earth Remembered

The sun rode high, a hard brass coin hammered flat against the pale sky. The hedgerows gave off the hot green smell of nettle and briar, and the tilled earth at Haroldstown shimmered faintly in the noon glare.

“It feels wrong,” Barbara murmured, shading her eyes as they crossed the lane. “As if something were waiting for nightfall even now.”

“Exactly why we come in daylight,” the Doctor said firmly, tapping his cane. “It will find the hour unflattering. Evil seldom enjoys the scrutiny of a summer noon.”

Keating, grim and reluctant, had admitted them to the field with no more than a muttered curse about strangers meddling with stones. He stood guard at the gate, arms folded, looking as though he would rather the dolmen swallowed the lot of them than be responsible for their safety.

The Doctor planted his cane and surveyed the ground. “We shall make an examination. Mr Chesterton, dig here, along the base. Miss Wright, keep your eyes open and your head clear. Susan.”

“I know, Grandfather,” Susan said, brave but subdued. “No listening.”

With that, Ian set to work with a spade borrowed grudgingly from Keating. The soil was heavy and close-packed, and sweat soon traced a dark line across his brow. The Doctor crouched beside him, every so often poking the ground with his cane, muttering measurements half in mathematics, half in something older.

After a quarter of an hour Ian struck something solid. A flat surface, smoother than fieldstone. The Doctor’s eyes gleamed.

“A covering stone,” he said softly. “Deliberate. Yes, yes, now,up with it, but gently.”

Between them, Ian and the Doctor levered the slab aside a few inches. A stale draught rose from below, cold in spite of the heat. The Doctor lit his lantern, and they peered within.

At first it seemed a chamber of rubble. Then Barbara gave a little cry and clutched Ian’s arm. The lantern light had steadied, and what she thought stones resolved into shapes.

Dozens of small figures crouched in the hollow, no larger than a hand: twisted, folded things, arms drawn over faces, mouths caught half-open as if in fear. Their clay-like bodies seemed at first inert.

Then one moved.

Its tiny head turned, just a fraction, toward the light. Its hollow eyes opened. Lips as thin as a scratch parted.

A sigh escaped it.

Another stirred. Another sighed. Soon the chamber was alive with a whispering chorus, not loud but unbearable, the sound of resignation given breath.

Susan clutched Barbara’s hand. “They’re alive,” she whispered.

“Not alive,” the Doctor said grimly, his face pale in the lantern glow. “Not dead either. Preserved, compressed, as one keeps wax cylinders to be played again. Human essence, captured to fuel the glamour above.”

The sighs grew louder. Then, horribly, the whispers seemed to form names.

“Barbara…”

“Ian…”

And, soft but clear, “Susan…”

Susan gasped and clapped her hands to her ears. “Grandfather, it’s calling me!”

The Doctor slammed the lantern shut. “Back! All of you, back at once!”

With Ian’s help he dropped the slab into place. It fell with a noise like a lid clapped over a mouth. The whispers ceased. The chamber was silent again, but the silence had weight, like a promise.

They staggered back into the bright field. The sky had not changed, yet it seemed dimmer, the light less certain. Keating made the sign of the cross and would not meet their eyes.

“Doctor,” Barbara said, her voice shaking, “what have we seen?”

The Doctor leaned on his cane, breathing hard. “You have seen the residue of centuries. The earth remembers what is placed in it. Something here has learned to take, and to keep, and to play. And it is not done.”

He turned, eyes fierce under his white hair. “Tomorrow at dusk it will sing again, and it will ask for a voice. But we shall have an answer ready.”

To be continued in Chapter Four: The Unplayed Note.

Chapter Four: The Unplayed Note

The evening came with the hush of expectation. Even the birds along the hedgerows seemed to pause their calls, as if unwilling to embroider the silence. The dolmen waited in its field, squat and innocent to any casual eye, yet Barbara could not look at it without hearing again the sighs from beneath.

The Doctor set down his satchel by the field wall with the air of a man preparing a lecture demonstration. He unpacked wire, bells, forks, and an instrument that looked half like a child’s toy and half like a relic from Babylon.

“Tonight,” he said, his voice brisk but a little strained, “we refuse the chorus. We shall not answer its call, no matter how sweetly it invites. Instead, we shall let it sing to itself until the harmony curdles.” He glanced at his companions. “If it names you, you will not answer. If it takes a step toward you, you will step away. Do you understand?”

Susan nodded, pale but determined. “Yes, Grandfather.”

Barbara’s hand was tight on Ian’s sleeve. “We understand,” she said firmly, for both of them.

The Doctor fixed his contraption to the hedge, adjusted a fork, and listened to the faint sour hum it gave back. Then he straightened, leaned on his cane, and gestured toward the field. “Let it try.”

The light faded. The air shifted, as if the world drew in a long breath.

The first note came, cold and bright. The hedgerow wires quivered, the bells fussed, the reeds whined. The music pressed on, weaving round their ears, seeking a path inward.

The glamour appeared.

The woman reclined upon the capstone, green velvet dark against the twilight. Her hair flamed copper in the last light. Her mouth parted, and the song wound like silk through the hedgerows. Beside her, the pale harpist plucked, his wooden chair sunk almost to its knees in the soil.

“Every ear that hears our song is chosen,” the woman said, eyes fixed on Susan. “One more voice, child, and you will never be alone again.”

Susan trembled, but she sang back, clear and stubborn, a snatch of “Greensleeves.” The glamour faltered. The harpist struck an ugly note.

The Doctor’s cane lifted like a conductor’s baton. “You have fed too long,” he said, voice sharp. “No more.”

The device whined. The wires screamed. The bells jangled out of tune. The glamour strained against the discord. The woman’s beauty cracked like glass, her song turning shrill. The harpist’s strings snapped one by one, each breaking with a sound like a groan.

The figures beneath the dolmen whispered once more, rising to a thin chorus. For an instant Barbara thought she heard them sigh their release.

Then silence.

The field was still. The glamour was gone. The capstone lay bare.

The Doctor lowered his cane slowly. “It is not destroyed,” he said at last. “But it is broken. Its harmony cannot hold. It may linger, it may wait, but it will not sing sweetly again.”

Barbara touched Susan’s shoulder. The girl was trembling, but she lifted her chin. “It tried to make me go,” she whispered. “But I didn’t.”

The Doctor’s eyes softened. “No, child. You answered with your own note. And that is the unplayed one, the one it cannot command.”

They gathered their things and walked back to the lane. Keating, at the gate, looked at them with a farmer’s suspicion of miracles, then turned his eyes to the dolmen and muttered a prayer under his breath.

The night deepened. The stars came out. Behind them, Haroldstown Dolmen crouched in silence. Yet Barbara, glancing back one last time, could not rid herself of the impression that the field itself still held its breath, as if waiting for a song that might begin again.

And in the hedges, the small bells tinkled once, though there was no wind.

The End