Saint George and the Dragon

St George and the Dragon in the Mirror

The messenger reached George at dusk. His horse came lathered and trembling, the leather of the saddle streaked with salt where sweat had dried in the wind. He spoke of a hall in the fen country, fallen to ruin, where no birds flew and no herdsman would graze his cattle. The hall was ringed with black water that took the sky like ink. Within, so said the messenger, the dragon was waiting.

George heard the words and put on his harness. He had fought beasts that burned crops to ash. He had severed necks that arched higher than the oak trees. He had seen scales as broad as bucklers and jaws that swallowed sheep whole. He had learned that fear was a language spoken by the living and that he could answer it with iron and prayer. He rode with three men-at-arms to the fen, and the road fell away beneath him as if it had never existed.

It was the kind of evening that clings to the skin. Mists rose like breath from the bog. The sun was a thin copper coin, pressed into cloud and forgotten. They found the hall at the end of a causeway built of stone that sloped downward into water. It had once been grand. A colonnade lay toppled in the reeds. A seal ring of some lordly finger winked in a muddy rill, glass where the gem had been. The door, when they pushed it, went open too easily and scraped the floor with a noise that sounded like a blade being drawn from a sheath.

“Stay with the horses,” George said. His men did not argue. He lit a lantern and stepped inside.

A cool draught moved over his skin. The lantern flame made a small crown on the floor and swung in the iron ring as he walked. The hall opened like a throat, then narrowed, then opened again, as if the building were breathing him in and out. George smelled lime and old wax. He smelled something else, faint as a memory, the scent of something that had once been sweet and was now gone.

At the far end of the passage a door hung crooked. Beyond it lay a chamber with a long, low ceiling and walls that glittered. George raised his lantern. The glitter resolved into mirrors, row upon row, set in frames of black wood. They stood from floor to ceiling, close as soldiers in formation. Some were clouded with age. Some were so clear he could have counted the stitches of a wound across a face seen there.

In the nearest mirror he watched himself arrive. The lantern showed him. A man in iron with dust at the knees of his cuisses. The red cross on his surcoat faded by weather and war. The face beneath the open helm burned dark by sun and pale around the eyes where sleep had kept its cost. He had imagined this encounter many times. He had pictured a beast. He had trained his horse to hold steady when the world shook. Yet no dragon waited for him on the floor. The dragon waited in the glass.

The first reflection that was not his own was a dark ripple that quivered across the surface, as if something had moved inside the silver. He took a step, and the ripple steadied into the shape of a long neck and a head like a wedge of onyx. It came so close that its breath should have fogged the glass, yet no steam appeared. The eyes were not red. They were a drained yellow, the colour of old parchment and sour wine.

“St George,” said the dragon, though its jaws did not part. The word reached him through the glass, without echo.

His first thought was to draw his sword and break the mirror. He did not. The blade was a last answer, and the first answers had not yet been given.

“Show yourself in the room,” George said, and raised the lantern higher. “Or name what trick this is.”

“My body is stone and smoke,” said the dragon. “I am seen where seeing is a wound. You are in my hall. The faithful have brought you, as the faithful always do, when they desire to see their fears take flesh and die by another’s hand.”

George took another step. In the mirror to his left he saw a dragon not of onyx but of ash. Its hide flaked like paper. It turned what could have been a grin upon him, the edges of its mouth charred and cracking. In the mirror to his right, a serpent coiled with the indolence of royalty on a barrow of bones. Its eyes were green like bruised apples. The long chamber gave back images of him and images of the beast, each slightly wrong, as if the world had been shattered and badly mended.

“You have killed many,” said the dragon. The voice came now from a different pane, then another, so that the sound moved like a lit candle carried hand to hand. “You have become a story told by strangers to hush their children at night. Do you know what story they tell the children when they are grown and their hushings have turned into hunger?”

George said nothing. Silence has weight in a place like this, and he felt his words would break something delicate that ought to be left intact if he could help it.

The lantern flickered. The mirrors caught the flame and multiplied it into a court of candles. In each, he was a different knight, as if the hall had decided to try out his face in a dozen variations. In one he was younger, mouth firm and proud. In another he was older and the mouth was harder. In the far right frame he was a stranger altogether, eyes a cool, merciless grey that he did not recognise as his. The dragon moved behind and through these figures as a shadow moves behind a column of passing men. Its neck crept past one shoulder, its claws raked the air behind another. No sound of scraping came from the glass. When it opened its jaws, George heard a bell ring once, far away, a single stroke that contained no time at all.

“What do you want of me?” George asked at last.

“Want is such a small word for what I am,” said the dragon. “But I will speak it as you do. I want you to know me. I want you to strike as you always have. I want to feel the end pass through me and into you.”

George set the lantern on the floor. Its light widened the circle of bright stone. He drew off his gauntlets and knelt. He made the sign that had steadied him on cliff paths and in shrieking smoke. The mirrors received the movement and gave it back. A hundred Georges bowed in a hundred panes. A hundred dragons peered over his shoulder to see what prayer would be chosen.

He spoke softly. He asked for clean sight. He asked for a hand that did not serve vanity. He asked that if the beast were his own, he would know it without mercy. When he stood again the joints of his harness clicked like teeth. He took up his sword.

The blade had earned its past slowly. It had taken lives in fair fight. It had kept others from dying. It had killed what could not be allowed to live. The steel looked thin in all this silver and still he trusted it as he trusted breath.

The mirror that held the onyx head was an arm’s length away. George measured the distance as if facing a living throat. Strike through the throat and the breath stops. Strike through the eye and the light goes out. Strike here, and end it. He stepped and swung. The glass broke in a clean starburst and collapsed inward, the shards sucking the torchlight into their scatter as if the room had been suddenly salted with darkness. The onyx head did not fall. It blinked, not in that pane but in another. He pivoted, cut again, heard the low clean note of a second mirror dying. The serpent with green eyes uncoiled in a third, spilling smoke across the boundary of the frame. George cut that one too, and the next, and the next, until the floor was a field of glitter and the air thrummed with the noise of unseen bells.

“Good,” said the dragon. The word was almost tender. “Carry on. I am many because you are many.”

George stilled. Sweat slid down his temple and left a pale ribbon on his cheek. The thought came to him, unwanted and true, that the dragon had not moved from the glass into the room because the room was not its body. The room was a throat. The mirrors were teeth. He was not tearing flesh. He was feeding something that ate the bright and the sharp.

He pressed the tip of his sword to the stone and leaned on the crosspiece. His breath slowed. He let the rush of the cut sink and settle inside him where old lessons live.

“You speak like a man,” he said. “Yet you do not show a man’s face. Show me yours.”

The dragon answered with silence that was not empty. It was full of listening. Then a mirror far down the chamber, one of the few still whole, clouded until it was grey as the underside of storm. When the cloud cleared, George saw a figure in armour there. It wore his surcoat. It had his height and his carriage. It did not carry his sword. It carried a lance, and upon the lance was hoisted a long, wet thing, limp and snagging on the barbs. George knew the feel of that weight in his hands because he had held it before. A head. The head of a monster that had terrorised a town. He had ridden through the town with that proof, the victory raised like a banner, and the people had opened their shutters and shouted his name with tears on their faces. In the glass, the head streamed a slow line of dark fluid and the crowd lay still in rows on the street, eyes open and empty. Flies gathered like incense. The knight in the mirror did not look at them. He lifted the trophy higher.

George took one step, then another. His throat had gone dry. He remembered that campaign. The head had been clean. The people had lived. The facts were firm. The glass was a lie.

“Is it?” asked the dragon, without moving its jaws.

The knight in the mirror turned his face. George saw his own mouth shaped in a smile he had never seen on himself. Contentment without pity. He paused, blade low, because the pause was honest. Then he closed the distance and struck, not with rage but with precision. The mirror shattered. The smiling mouth went to dust with the rest.

“You are not the first to find yourself here,” said the dragon. Its voice had come nearer. “Some break every glass. Some break only the ones that flatter them. Some never lift the sword at all. Each thinks he is the only kind of man he could be.”

George looked along the chamber. There were fewer mirrors now. He could see places where the wall showed naked between them, patched with lime like old scars. The air held a taste of metal and something else, bitter on his tongue. He counted the remaining panes. Seven, and one narrow strip that had somehow survived along the doorframe unbroken and unnoticed, catching only a sliver of him, a sliver of something tall and dark behind him that was perhaps a trick of angle.

He lifted the lantern again. The surviving mirrors gave back the light anxiously, like eyes expecting a blow. In the nearest he saw not himself but a child with hair as black as spilled ink and eyes wide with the kind of fear that is learned from adults. The child wore the torn livery of a household George had once defended. Behind the child stood a shape that might have been a dragon and might have been the shadow of a banner. The child raised a hand to him in the old gesture for mercy.

He did not strike. He did not sheathe the blade either. He set the lantern at the foot of the frame and stood with the weapon upright and still, as one stands guard over a gate. The child did not move. After a while the image thinned, the way hunger thins the body, and became no more than an afterthought in the silver.

In the next pane he saw a woman in a white veil sitting on a stone. She did not look at him. She looked at the veil pooled in her lap, as if it were a map of a country she had left. He had rescued her from a dragon with wings like rows of knives. He remembered the bruises on her arms where claws had touched. He remembered that after deliverance she had not smiled, not even once, and that he had been puzzled by her quiet because he had not understood that the absence of a monster does not fill a life.

He touched the glass with the flat of the sword. The woman’s veil trembled as if a breeze had found its way into her world. Then she too faded.

“You ask to see my face,” said the dragon. “You are patient with the faces of others. How patient are you with your own?”

There were five mirrors left. In one he was mounted, lance couched, riding across a desert of bones. In another he knelt by a spring, washing blood from the edge of his sword and looking not weary but eager. In the last but one he slept in a field with his helm off and the grass bright about him. A shadow fell over his face in the image, a long curved shape that slid like an hour across a sundial. He had no memory of that hour. The glass had stolen something and preserved it.

“Enough,” George said, and the word felt like a blessing. “Show me how to end this.”

The dragon moved in the farthest pane. Not the reflection of any man now. Not smoke or stone. A creature of ironwood and night. A ridge of spines that were not spines but the staves of broken standards, their silk burned away. A throat that suggested a furnace throat. Claws that called to mind the hooks of a smith’s rack. It had been built by many hands, taken apart by none. Its smile was an accident of angles.

“You end nothing,” it said. “You change the place where the ending occurs. If you break the glass, you break me into smaller pieces. If you leave it whole, you allow me to remain a single wound. What kind of wound do you prefer to carry?”

George thought of the people who had sent for him. He thought of the messenger’s horse, blown and shaking. He thought of his men-at-arms waiting on the causeway, heads bowed, hands close to the bridles of beasts that were not sure they would ever see their riders again. He thought of the woman on the stone, the child with the lifted hand, his own face smiling the way he had despised. There are many answers to a question. Only one will be lived.

He slid the sword back into its scabbard. The sound it made was modest. He took the lantern and walked to the narrow strip by the door that showed him in slices. The tall dark shape behind him did not change. It held itself as a question might hold itself when it has been asked for too long.

“Come out,” he said to that shape, to the hall, to the voice that spoke in silver. “If you would be ended by me, be ended where my blade can reach you. If you will not, then you will starve here.”

“Starve?” The dragon made the word new, as if it had never had need to pronounce it.

“You live on fear arranged into stories,” George said. He felt the rightness of the statement as a craftsman feels the rightness of a joint that seats true. “You eat the cry that a man drops when he sees himself and flinches. You drink from the well of misremembered victories. You chew the bright, flattering lie. I will give you no more food. I will take your hall and strip it. I will lead those who hired me through this place until the glass holds only their faces and then I will take even those away. I will let daylight in and keep it in.”

The dragon did not answer at once. The mirrors hummed, the way strings hum when a harp is set near thunder.

“You have tried steel,” it said. “Now you try poverty.”

“Not poverty,” said George. “Sufficiency.”

He lifted the lantern and turned toward the door. The narrow strip of glass caught his eye again. In it he saw himself framed by ragged silver, already smaller. Behind him the long chamber lay like a drawn breath that would at last be released. He walked out and the strip held him a moment more, then only the lantern, then only a bright smear, then nothing at all.

The men waiting by the horses looked up as he came. They searched his armour for scorch marks and found none. They searched his face for a story and saw that he had brought one, though he had brought it without trophies.

“Well?” said the eldest, who had ridden with him longest and had learned not to decorate questions.

“It is a hall of mirrors,” George said. “We are going to take them down.”

They set to work that night. They fetched canvas and rope. They wrapped each mirror in cloth before they moved it, so that it would not glance at them by accident and tip its little weight of fear into an unwary hand. They lifted them from their hooks, which were shaped like the tongues of saints, and carried them over the causeway to a cart. The fen received them without remark. Owls watched with yellow stones for eyes. Once, far off, a bell rang a single note and did not ring again.

George worked until his shoulders throbbed and his palms buzzed. He took the panes down as he might take weapons from an armory that would never be used again. In some the glass had begun to blacken in the corners, as if mildew had learned ambition. In others the silver had peeled like skin. In one he saw his hand reach for his hand and he paused, not from fear but from a sober sense of trespass, then lifted it down with the same care as the rest.

They burned the frames for heat. They stacked the glass in the cart and threw a thick tarpaulin over it. In the morning they drove away from the fen. George did not look back. He had learned to look away not from shame but from completion. There is a kind of looking that eats what it looks at until both are gone.

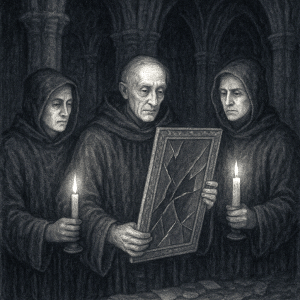

They took the mirrors to the abbey that lay three days’ ride from the fen, where the brothers could grind the silver for medicine and the glass for sand, where the frames could be carved into new shapes that would not bite. George stood with the abbot in the workyard while men hammered at the lead that bound the panes and women carried the strips of backing to a table to be sorted into salvage and waste.

“You saw it then,” said the abbot, not as a question. He had the kind of voice that had learned to leave room in its own words.

“Yes,” said George. “I did.”

“And you killed it?”

George watched sunlight lie down across the stone like a tame cat. He watched a novice drop a sliver of glass and jump at the clatter, then smile in relief when the sliver did not cut him.

“I changed its diet,” he said.

The abbot laughed once, a single clean sound. He nodded as if a point had been scored in a game he liked.

“You will meet it again,” he said. “We all do.”

George did not argue. He did not fear the next meeting, not because he thought he would win, but because he had learned the shape of the field on which the game was played. He reached into his purse, took out the seal ring he had found in the rill at the hall, and set it on the table in front of the abbot.

“Give this to the poor,” he said.

“Which poor?” asked the abbot, who was exact.

“The ones who most often mistake their hunger for someone else’s,” George said. “It will find them.”

When he left the abbey, the road shone in front of him like a blade that had been polished with care. His horse flicked an ear. The day was clean. He rode lightly, though the harness was the same weight as always. Somewhere a bell began to toll for the hour. It sounded like iron. It sounded like water poured into a bowl. It sounded like a word that answers a question without ending it.

On the third day he came to a village where candles burned in every window even though the sun stood high. The people told him of a darkness that pressed against the shutters when night came and of a voice that whispered in the keyholes. He listened. He ate their bread and tasted no ash in it. He slept beneath a roof that creaked like a friendly ship. In the morning he sent his men to fetch wood and oil and said to the elders that they would open every window and every door and keep them open until noon. The elders asked why. He said he had brought a story and that the story would teach them to let light do some of their work.

They did as he asked. The wind moved through the rooms. The candles guttered and went out. Nothing pressed at the shutters. Nothing whispered through the keyholes. The sunlight laid a clear hand on every sill.

It was not the last village he served in this way. It was not the last hall he emptied. The dragon kept its old names and learned new ones. It found other mirrors. It learned how to hide in water, in armour, in the small glinting pride a man feels when he is told that he has been right all along. It learned, too, that there were places where it could not feed because someone had taught the people there to look and to go on looking until the thing in the glass became no more than a picture painted for a feast that had been cancelled.

Years later, on a hill above a city that called him its guardian and would have built a statue of him if he had let it, George woke in the night and found that he had slept with his helm at his side. He lifted it and saw, in the curve of its metal, two small moons of reflected fire from the hearth. For a moment they were eyes. He did not flinch. He turned the helm in his hands until the moons slid away and became only what they were. He set the helm down and slept again.

He dreamed of the fen. In the dream the hall was not empty. A boy stood in the doorway, a rope in his hands, a lantern at his feet. He looked at the mirrors and then at the rope and then back at the mirrors, uncertain. George reached for him, not with a hand, but with a word, and the word was simple. Light. The boy understood. He lifted the lantern and the hall accepted what it was given.

When morning came he rose, washed, and went about his work. People spoke of dragons. He listened. He rode. He fought when steel was needed. He kept his voice when silence would offer the wrong kind of shelter. He left rooms brighter than he had found them. Wherever he went, he did not take trophies. He left doors open.

Epilogue

Years later, long after George had ridden his last road, the abbey where the mirrors had been broken was struck by lightning. The fire burned hot and sudden, yet when it was quenched, the monks found one shard of glass untouched amid the ashes.

They set it in a frame and kept it as a curiosity. At first it showed nothing but the pale reflections of cloisters and passing clouds. But on certain nights, when the moon was thin and the bell tolled late, those who dared to look swore they saw a knight in iron walking down a hall of shattered mirrors.

Behind him, just for an instant, something vast and patient stirred — waiting for the day someone else would raise a lantern and step too close.