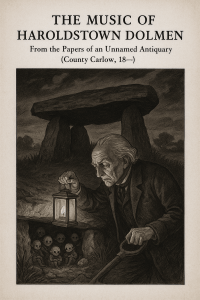

The Music of the Dolmen

The Music of Haroldstown Dolmen

From the Papers of Dr Laurence Hartwell (County Carlow, 1864)

I do not pretend to offer an explanation for what follows. I set down only what was told to me and what I, to my shame and terror, saw with my own eyes. Others will dismiss it as country superstition, or as the hallucination of a gentleman over-tired by walking and over-stimulated by parish gossip. I would welcome such a verdict if only sleep had welcomed me since.

The monument in question stands in a tilled field three miles from Tullow: the Haroldstown Dolmen, two vast capstones supported by eight uprights, the cairn long vanished and the skeleton of the thing left exposed to the sky. Borlase calls it “remarkably preserved,” and Wakeman notes its “grim solemnity seen against the bare horizon.”¹ ² Neither gentleman, to my knowledge, mentions its music.

I first heard of the latter from Keating, the farmer upon whose land the dolmen stands. “You’ll not find my sheep grazing there after dusk,” he said, with a look toward the field that made the daylight seem a thin defence. “My father heard music from it once, thin as frost, sweet as poison. We found two ewes dead next morning with their mouths full of clay.”

A butter-seller, one Mrs Ryan, gave the detail that set me upon the road that evening. “I saw her when I was a girl,” she said, crossing herself without fuss. “Hair like a fox’s brush, gown like moss, and a voice that would pull your ribs together. Lying upon the big stone as if it were a chaise, and a thin fellow in a chair beside it, playing a harp. I came away. Not all do.”

A parish entry of 1796 confirmed a pattern I would later recognise with a horror beyond words: *Patrick Byrne, labourer’s son, did not return after eventide. Cap discovered upon the monument at a height no man could reach unaided.*³ A later memorandum of 1839 notes a travelling fiddler gone missing, his bow found broken upon the capstone. No bodies were ever recovered. Only tokens remained, as if the stone, like a customs officer of the dead, retained proof of transit.

I walked out toward Haroldstown at the lowering of the sun. The lane was edged with nettles and pale dog-rose, and a rook balanced like an ink-blot upon a wall. The dolmen stood solitary in its field, the capstone’s shadow a dark door upon the soil.

The first note came without warning. I felt it in the ribs rather than heard it in the ear: a harp-string, bright and cold, followed by another, weaving a melody too sweet for mercy. I stepped to the gate. What I saw in the field I would trade a great deal not to have seen, though I should as likely trade as much to see it again, such is the contradiction of the human heart.

Upon the capstone lay a woman, reclined as though the old stone were a chaise of velvet. Her hair was red as new-coined copper, her gown a green that drank the light. She sang without words, or rather, the air about her sang, and her parted lips allowed it to pass. At the foot of the dolmen, on a plain wooden chair (how it had come there I cannot imagine), sat a gaunt man, pale as candle-wax, his eyes cast down upon the strings of a harp. The chair-legs were sunk a little way into the ground, as if the earth had been swallowing them by degrees.

The song drew me forward as a tide draws a wisp of weed. Sweetness is a dangerous thing when it is not wedded to goodness. I know of no other word to describe it. The woman turned her head and regarded me with eyes the colour of water over glassy stones.

“You hear us,” she said very softly. “Most do not. Every ear that hears our song is chosen. We need one more voice.”

At this the harpist struck a single note, brittle as ice touched by a nail. The dolmen shivered, and the nettles about my ankles seemed to creep higher. The field lengthened. The hedges retreated as if shy of the scene they bordered. I do not know how far I should have gone if a small cloud had not, providentially, walked across the sun and cooled the air by a hair’s-breadth. In that instant the glamour loosened. I found I could turn. I did so, stumbled, and gained the lane with a strength I did not know I possessed.

When I dared look back the capstone was empty, the chair gone, the field very ordinary in the last of the light. Only my breath went like a saw, and a tune I had not learned had lodged like a fish-bone in the throat of my mind.

I slept badly that night, if sleep can be called the tossing of a man who cannot keep from his inner ear a sound that is determined to be heard. The following morning I told my host only that I intended to examine the monument by daylight. I did not speak of the woman in green, nor of the harpist, nor of the sentence that had entered me like a splinter.

I took with me a spade and a lantern, and under pretence of retrieving a misplaced glove obtained Keating’s reluctant permission to enter the field. A gentleman’s assurance and a silver coin bridged the rest.

The soil beneath the capstone proved heavy, damp, and watchful. After an hour I uncovered a flat stone distinct from the field-rock: a paving laid by a hand that had not cared to be elegant but had insisted upon intention. I worked my fingers under its edge, raised it by inches, and set the lantern to peer within.

Expecting bones, I saw instead a multitude of small forms, crouched and huddled, no larger than a man’s hand. At first glance, one would have said crude dolls of clay. Then the flame steadied, and one of them moved. The tiny head turned, a fraction only, toward the light. Pin-prick hollows opened where eyes should be. Lips as thin as a scratch parted. It sighed. Others followed suit, until a dozen such faces had lifted from the heap and a whisper rose from them that was not speech and yet contained, horribly, the freight of meaning.

No human congregation could have produced such a sound. It was the breath that follows a sob held much too long. It was resignation given the shape of air. I am not ashamed to confess that my hands shook, and the lantern wavered. I let the slab fall, clapped it shut, rather, as one claps a hand over a mouth that must not be allowed to utter a name, and staggered back, the taste of cold iron in my mouth.

On the morrow I returned with Keating to fetch my spade, which I had left in my panic. The soil lay smooth. No sign remained of my disturbance. The spade was gone. Keating swore, and would have sworn more if his fear had not begun to gnaw at his anger.

What, then, are we to conclude? I set down a few facts, such as I can bear to call them by that name.

- The glamour above the stone, the woman in green velvet and the gaunt harpist, appears near dusk and employs a song that compels approach. That it is a lure I no longer doubt. I will not call either figure a woman or a man. The first has the appearance of beauty, the second of function. Neither cast a shadow that I could mark, though the light was such as would have favoured one.

- The chamber beneath contains (or appears to contain) small figures, crouched, that at first present as fashioned clay but which exhibit a motion that cannot be accidental. Whether these are the remnant of those taken, reduced and preserved in a form I will not name, or whether they are instruments of the thing that sings, I cannot bring myself to decide.

- Tokens left above, the cap of the labourer’s boy, the broken bow of the fiddler, perhaps my spade, imply a transfer that leaves a sign. As if the stone accepts a toll.

- The harpist may be more than a companion to the glamour. The single note he struck altered the air, and the dolmen trembled. I am persuaded he conducts the sighs below and draws them up, through whatever hidden threads bind chamber to capstone, to become the woman’s song. I do not assert this, I confess it as a conviction.

There are more testimonies. A magistrate’s private journal in 1854 records a youth who saw the pair at twilight and henceforth could hardly speak above a whisper; he hummed, they say, a tuneless air that froze his neighbours’ blood and died at twenty-one without recovering his fullness of voice. An old woman on the Carlow road told me, and would tell me no more, that she once passed the field and felt her late husband walking beside her until she looked down and saw his boots were full of earth. I leave these here as I received them, with reluctance.

You will expect me to have devised some remedy. I own I am not without contrivance. A gentleman’s tuning-fork introduced a small discord into the air when flung, by accident, against the dolmen’s flank. Upon the instant the glamour lost a little of its purchase and the figures abated. I am convinced that a lattice of disagreeable resonances might tangle the song in hedgerow and wire and permit the cautious to pass by with less danger. Whether such measures would free those beneath, I dare not hope. A prison’s gate is not unlocked by making its bars sing out of tune.

I am asked, by my own conscience if by no other advocate, why I did not dig again and make an end of doubt. I answer that I am a coward and wish very much to remain one. Besides, there is this: when I lowered the lantern, the whispers rose, and among them, for a breath like a knife’s-thickness, I thought I heard my own name. We who have looked too long into a mirror at dusk will forgive me for dropping the stone.

If any man who reads this is tempted by the sweetness of a song in a field at sundown, if a red-haired lady’s voice promises that he is chosen, that one more voice is all the choir lacks, I entreat him to think of the small figures huddled below the capstone and ask himself whether he cares to be reduced to what can be played. If he is determined to go nevertheless, let him at least take with him a pocket of iron filings, a fork of tuning, and a friend who will be rude enough to seize him by the sleeve and say, “No.”

As for me, I have not returned to Haroldstown, and do not intend to. Yet there are evenings when the ink dries too quickly on my pen and the light in the window-glass takes on the colour of the dolmen at dusk, and I find that I have set down, upon the paper before me, not the figures of a ledger but the outline of a chair’s leg sinking a little deeper into earth. Then I hear, faint but there, one bright note, as of a string plucked far off. I pause, and the silence afterward is so heavy with waiting that I must fill it at once, talk aloud, cough, drop a book, anything, lest a voice like water over stones should say to me, and to me alone, Every ear that hears our song is chosen.

I would like to assure myself that such a sentence has the general form of a lie. I cannot. The truth is that, having once heard it, I continue to listen. This, I think, is the trap’s finest tooth: that those who escape the field do not entirely come away. Something under the stone counts us as if we had already descended, and is patient.

Dr Laurence Hartwell, Carlow, 1864

Notes

- Borlase, The Dolmens of Ireland, vol. II, p. 447.

- Wakeman, Handbook of Irish Antiquities, p. 212.

- Tullow Parish Record, vol. iii, fol. 27 (1796): entry attested by curate; transcript in the editor’s possession.