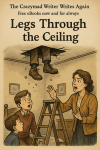

Legs Through The Ceiling

Legs Through the Ceiling

Many years have passed since the Big Freeze of 1963. It seems like a lifetime ago—another place, another world. A world so far removed from the one we now enjoy, and so often take for granted. Life today is easier, warmer, more connected. Back then? Not so much.

They called it the Swinging Sixties. To this day, I’ve no idea why. Despite all the supposed social revolutions, most people trudged through the same dull, joyless routines they’d always known. And yet, they truly believed they were living through a time of great progress—an age unlike any before. That, I must tell you, was a serious delusion.

There were no computers. No internet. No satellite TV to inform or distract. We had television, yes—but it showed grainy black-and-white pictures on pitifully small screens. Newspapers? They reported yesterday’s news, and not particularly well. It was a dark time—made darker still by the fact that no one realised how dim it truly was. People thought they were marching into Utopia, but the doors to that particular paradise were firmly shut.

Now, more than forty years later, I ask you: what truly worthwhile came out of the 1960s? And no, I don’t mean the music or mini cars or psychedelic trousers—I mean something genuinely worthwhile.

Got you thinking, didn’t I?

The truth is, the big, meaningful, transformative changes came much later. The Sixties, for all their noise and colour, were a superficial, drug-fuelled hallucination. Scratch the surface, and what do you find? The same old hypocrisy. The same old discrimination. The same old boredom.

Yes, some people stood up for what they believed in—but only when surrounded by others doing the same. It was a herd movement, not a heroic one. Unlike Gandhi, most fell silent when left alone. That’s why I say again: the 1960s were a time of delusion.

And that brings me neatly to my story.

Because of the severity of that winter’s freeze, the pipes in our attic froze solid—along with the water tank. Determined to fix things, Dad borrowed a blowlamp from Uncle Eric.

“I’ll defrost those pipes, so I will!” he declared, climbing the stepladder—torchless, but full of purpose.

In those days, houses had no insulation. When it got cold, it stayed cold. I can still remember lying in bed, listening to the glass in our steel-framed windows crack under the frost. It was brutal.

“Are you alright, dear?” Mum called up to the attic.

No answer.

“Jim!” she called again. “I said, are you alright?”

“Hello?” came Dad’s strange, singsong reply.

“I said, are you okay?”

“Yes, I’m fine,” he said. “Bit dark up here, though…”

“Have you got the torch?”

“No. Forgot it.”

“Shall I pass it up to you?”

“No; I’ll come down and get it.”

And then—

CRUMP.

“What was that?” Mum asked.

Silence.

“Jim? Are you alright?”

Incoherent muttering drifted down.

Then came the shouting and swearing. “XXXX! You MADE me do that, so you did!”

“What did I make you do?” Mum asked carefully, hoping to avoid more bad language.

No reply. A few minutes later, we heard him shuffling about again.

Another thud. More grumbling. More swearing.

My brother and I crept up the stairs.

“Did he bang his head?” we whispered.

“Shush,” Mum warned, peering anxiously into the attic.

Suddenly, a blast of icy air blew down. “Dad, where are you?” she called.

No reply.

“You boys, go to your room,” she ordered.

“But it’s freezing in there,” we protested.

“Go! I won’t take no for an answer.”

We obeyed, but didn’t play. We just sat there, worried. Until we heard a crash. Then a smash.

“MUM!” we shouted. “THERE ARE LEGS IN HERE!”

“Legs?”

“DAD’S LEGS! THEY’RE DANGLING THROUGH THE CEILING!”

“If you’re telling me fibs, I’ll get the wooden spoon!” she warned, rushing in—only to gasp in horror.

“JIM! You’ll fall right through the ceiling and kill yourself!”

More panicked mumblings from above.

“Gerrard—get the stepladder!” she cried. “Quickly!”

Though only nine and struggling with the weight, I dragged it over and placed it under Dad’s flailing legs.

“Go on, up the ladder,” Mum instructed. “Try and push him back up!”

Me? Push him up? If he fell, I’d be flatter than the ceiling board he just smashed through! But I did as I was told.

“Jim,” she shouted. “Gerrard’s under you. He’s going to push you back up. Ready?”

The mumblings turned frantic. Bit by bit, I managed to push Dad’s legs back into the attic. We all cheered when he disappeared from view. We cheered again when we heard him crawling to safety. We stopped cheering when he banged his head on a beam—followed by yet more swearing.

Eventually, he came down the ladder, covered in plaster dust and cobwebs, with three massive lumps on his forehead.

“Take this,” he barked, handing me the blowlamp. It was stone cold.

Then to Mum: “You take this.” He handed her a torn piece of roofing felt.

She examined it silently, not daring to ask where it had come from.

“The roofing felt’s shot. Came off in my hand. The whole lot needs replacing.”

“And the ceiling board up there?” he added. “Useless. Crumbled the second I stepped on it. That’s why my legs came through.”

My brother and I exchanged looks of disbelief.

He’d walked on the plasterboard, not the joists!

“It was only the timber that saved me,” Dad muttered. “Had a leg on either side of a joist.”

We cringed at the image.

“They don’t build houses like they used to,” he grumbled.

We were cold that night. And for the rest of the week, until workmen came to patch the ceiling and replace the roofing felt. By then, the pipes had thawed on their own. Dad never ventured into the attic during a freeze again.

Do I look back at the 1960s with nostalgia?

No. I look back—and shiver.

THE END