The Pink That Ate Tullow

Chapter One — A Bit of Colour

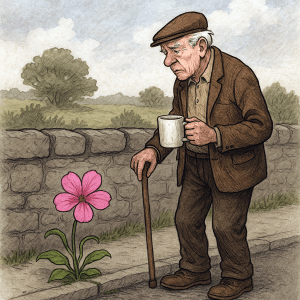

On a Monday that couldn’t decide whether it was late March or early April, the sky above Tullow was the colour of milk left too long in a teacup. Lambs bawled in the fields. The Slaney slid past, greenish and uninterested, as it always did. On Bunclody Road, Old Tommy Doran shuffled down to his gate with a mug of tea and his good knee behaving itself for the first time in a fortnight.

He stopped because something had happened to the ditch.

It hadn’t exploded or caught fire or sprouted a fairy ring. Nothing dramatic. Just a single flower, standing where last week there had been nothing but nettles, dog daisies, and a plastic Tayto bag that had weathered three winters.

The flower was pink. Not wishy-washy, not the honest pink of a lad’s sunburn after a match, but a soft, decisive pink with a sheen to it, like satin ribbon. Five petals, each curving inward as if to whisper a secret to the middle. A scent drifted up at Tommy — not strong, but definite — something like warm honey with a guilty lick of strawberry jam.

“Ah now,” Tommy said, because in Tullow that covers admiration, suspicion, and mild dread. He crouched until his creaking hips threatened strike action and peered. No thorns. No leaves either, oddly — just a slender green stem, like a tight coil unfurling. “Must be one of them hybrids,” he decided, with the authority of a man who had never in his life bought anything described as a hybrid. He sniffed again, felt a small, foolish happiness creep in behind the eyes, and stood up before it could settle.

“Out with you,” he told a blackbird, who hadn’t asked to be spoken to. Then he sipped his tea, watched a cloud try to be a sheep and fail at it, and wandered back up the drive. The dog, a retired chancer called Mayo, trotted behind him and never looked at the flower once.

By lunchtime, Tommy had told three people in the post office, one in the chemist, and everyone listening at the window of the Credit Union queue that he “had a foreign yoke blooming in the ditch like a posh wedding.” News in Tullow travels at the speed of whoever’s got the best shoes, and because Mrs. Kavanagh from the butcher’s was in her good black flats, she took it in hand and got it to Main Street in fifteen minutes.

“Pink, is it?” asked Brendan Kavanagh, sharpening a knife longer than his forearm. “Like the roses up at Altamont?”

“Pinker,” said his wife, counting six chops and making it seven if the customer looked like they needed it. “Tommy says it shines.”

“Shines how?”

“Like money,” said Mrs. Kavanagh. “But useless.”

By Wednesday, another one had appeared. This one pushed between the paving slabs outside the post office, perfectly centred as if it had consulted a spirit level and two committee meetings. The town stood around it, politely, the way you do when someone’s blocked the supermarket aisle with a trolley and a grand opinion about the weather.

“Isn’t it the loveliest?” sighed Nora Dowling, who’d been born with a sigh in her voice and had never once regretted it. “Like a blessing.”

“Or a statement,” said Councillor Byrne, already calculating whether there might be an award for prettiest streetscape. “We could make a feature of it. Small sign. ‘Welcome to Tullow — Town of Blossoms.’ Something like that.”

“What if it’s invasive?” asked Seán O’Malley, who said things like that because he’d been to Australia on a three-week working holiday fifteen years ago, and now everything was invasive to him. “They have plants there that’ll climb into your shoes at night and set up a second mortgage.”

“Sure, it’s only one,” said Nora, kneeling with care, as if the flower might need reassuring. “And look, it’s after making the place feel… I don’t know… fancy.”

No one stepped on it. No one picked it. There was no sign of soil in the crack it had chosen; it seemed to have installed itself the way good gossip does — suddenly, decoratively, and with no explanation that would stand up in court.

Father Donnelly passed by in his tatty black overcoat, saw the pink flare in the grey morning, and gave it a quick blessing in case it mattered. “Deo gratias,” he said to nobody, and to the flower if it was listening, and moved along with the mulish gait of a man who had learned to make peace with bad shoes.

Inside the post office, Mrs. Hession clicked her tongue six times in a row — her record for the week — and declared that whoever was planting them wanted attention and should instead try baking. Baking, she believed, was the proper route for all unspent human energy, including warfare.

The flower did not share its motives.

On Thursday, Mrs. Molloy stepped outside her café and found two blossoms had arranged themselves at the foot of her little blackboard sign. The board was freshly chalked: TODAY: CARROT CAKE, LEMON DRIZZLE, BROWN BREAD. SOUP: POTATO & LEEK. The flowers framed the list like quotation marks in a love letter.

“Oh,” she said — not startled, because life had already thrown every startle at her and found her steady — but pleased in a way that made her shoulders drop. She bent and inhaled. The scent nudged her mind toward the first dance at her wedding and then, very gently, toward the last time she’d kissed her husband’s hair in the kitchen, with the radio low and the kettle pretending to be rain.

Customers noticed. Of course they did.

“You’re after sprucing the place,” said Ned Doyle, who prided himself on spotting changes in the fabric of reality.

“Nature did it,” said Mrs. Molloy, pouring him tea. “And God, if you’re counting.”

“I’m counting,” said Father Donnelly from his corner table. “Always counting.” He wrote something in a small notebook that might have been a sermon and might have been a shopping list.

At eleven, two tourists in expensive walking gear took photos of the sidewalk, and of each other looking delighted by the sidewalk. At noon, a bee the size of a thumbnail crashed drunkenly into the window, bounced, recovered, and wandered off as if it had appointments.

Brendan came across at three to show Mrs. Molloy a new thumb scar (“Nothing sayin’ meat like a bit of yourself in it”) and stood with her in the doorway a moment. The air had a sweetness to it that made him think of summer fairs and bad decisions.

“It’s fierce nice,” he admitted.

“It is,” she agreed, then frowned. “Do you hear that?”

“Hear what?”

“Nothing,” she said after a second. “Or something. Like a humming in my fillings.”

“Could be the fridge,” he said, because men whose trade involved sharp steel and honest blood trusted machinery and distrusted sensations. “I’ll take a look if you want.”

“No, you’re grand,” she said, and the humming — if that’s what it had been — was gone.

By Friday morning there were five more. One had taken the trouble to place itself exactly between the iron rails outside the convent school, as neatly as a ribbon on a prize cake. Two had climbed — there was no other word for it — the stone wall behind the forge, leaving no trace of scratches or scrapes, only a notion of upwardness. The last two had bracketed the red post box like small astonished ears.

“Who planted them?” children asked mothers in tones that suggested Santa and the Tooth Fairy might have careered into flowers as a side hustle.

“Nobody,” said the mothers, because sometimes that’s the most comforting lie, and sometimes it’s also true.

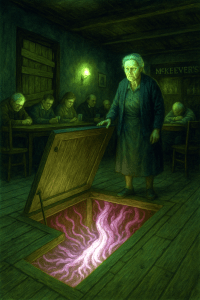

At McKeever’s, the noon crowd gathered despite it being 11:40. Mrs. Doyle lined up pint glasses like little glass soldiers and refused to be drawn on the proper swelling of cream on a Guinness because she believed knowledge should be earned by the asking, not given away free with the straws.

“You’ll have to do a flower gin,” Patsy suggested. “Colour to match, you know. Tourists love a theme.”

“I’ll do a flower gin when a flower pays me VAT,” said Mrs. Doyle, polishing a glass to a shine seen only in television adverts and funerals.

“It’s decorative,” said Ned, settling his elbows. “Like the baskets we had that summer before the great hanging-basket collapse.”

“That was only because you watered them with Smithwick’s,” said Mrs. Doyle, unable to keep the affection out of her scolding.

“And they were thriving,” Ned protested. “Until they weren’t.”

“Everything thrives until it doesn’t,” murmured Father Donnelly from the snug, which made everyone briefly aware of mortality in a way that improved the taste of their pints.

The door swung open and in came Councillor Byrne with the air of a man who had been to a meeting even if he hadn’t. “Right,” he announced. “I’m forming a Streetscape Appreciation Initiative.”

“You’re what?” asked Mrs. Doyle, because she always asked the hard questions for free.

“Posterity will thank us for recognising what we’ve got,” he said, pointing at nothing in particular. “There’ll be postcards, online campaigns — #PrettyTullow — and a small launch with sandwiches. Triangles,” he added, to demonstrate ambition.

“Is the council going to water them?” asked Patsy, deadpan.

“They don’t need watering,” said Nora, who had floated in, a cardigan around her shoulders like a cape for sensible heroines. “They’re not… well, they’re not like anything I’ve seen.”

“Everything’s like something you’ve seen,” said Byrne cheerfully. “Otherwise you couldn’t see it.”

“Philosopher,” said Mrs. Doyle, popping three packets of crisps. “Salt and vinegar. On the house because I like your confusion.”

The bell above the pub door tinkled once, and a draft carried in a smell so faint and so sweet that for three seconds every conversation paused. Some part of the collective mind leaned toward the memory of first days: first sweets, first shoes bought new, first kisses so clumsy and earnest they might have been prayers.

Then Ned coughed, which scattered the moment like pigeons, and somebody mentioned Kilkenny’s chances, which given recent form was the socially acceptable way of invoking the end of all things.

That evening, a purple sky rolled down from the Wicklow hills and buttoned itself to the roof of Carlow. Tommy sat on his stoop with Mayo, who had one milky eye and the wisdom to keep it to himself. “It’s a flower,” Tommy told the dog, in case there’d been a misunderstanding. “It’s a nice one. Nobody ever died from a nice flower.”

Mayo’s tail thumped twice. He was a generous listener.

From across the fields came the faint laughter of teenagers who believed they were the first to discover fields, and the sharper laughter of rooks in the big beech by the old mill. A bat scribbled something rude across the face of the moon. In the ditch, the pink flower breathed its thin perfume into the cooling air in small, measured exhalations, like a singer warming up.

When the breeze dropped altogether, a hush fell — one of those Irish hushes full to the rafters with sound: cattle shifting, pipes settling, a radio in a kitchen three houses away giving out the long list of things that had happened in faraway places to people with different weather. Tommy closed his eyes for a moment and saw, very clearly, his mother’s kitchen wallpaper: vines with impossible grapes. He opened them again and found himself looking straight at a second flower, six inches to the right of the first, that he swore hadn’t been there when he sat down.

“Right,” he said, and stood up in the cautious way of a man making a treaty with his joints. “Enough of that.”

He fetched his old yard brush, more bristle than handle at this point, and prodded gently. The flower bowed like a polite girl at a feis and then stood upright again with the stubbornness of a queue.

“Fair play to you,” Tommy conceded. He didn’t prod a second time.

Mayo considered the new blossom and offered it the same calm disregard he reserved for everything that wasn’t a sausage, a cat, or the postman’s unguarded ankle.

Saturday morning, Market Square. The stalls went up with the usual muttered choreography. Potatoes in earthy pyramids, carrots with their green hair still attached like they’d run away from home and been snatched at the gate. Cakes under cling film domes. Socks as far as the eye could see. Over all of it, faint and definite, the sweet, magnetic smell.

“Jaysus, it’s fierce cheerful,” said Mrs. Molloy, laying out slices of brown bread like the Eucharist of sensible people. “If I were a town, I’d want a bit of this.”

“Don’t go giving it ideas,” said Brendan, whose van had acquired two blossoms in the rubber seam of the windscreen. He had tried to pluck them and discovered that you can’t pluck a thing that isn’t quite attached. You can only hurt your fingers and feel a bit foolish.

Children chased each other around the water pump and then stopped, one by one, to look at the flowers as if consulting a stranger about the rules of a game. Nobody touched. It didn’t seem forbidden so much as… discourteous, the way you wouldn’t poke a stranger’s lapel flower without being formally introduced.

At eleven, a woman from Kildare asked if she could buy a stem to take home for her sister’s wedding. At eleven-oh-five, she changed her mind and took a photo instead. At eleven-ten, the photo refused to show the flower properly — it came out as a vague blush of light no matter how she angled it — so she deleted it and decided to remember with her eyes like people in old paintings.

At noon, the post office flower had acquired a twin, and the two of them swayed together as if listening to a tune nobody else had quite learned yet. If you stood near them (and many did, trying to be casual about it), you might have felt the slightest vibration through your shoes. Not a rumble, not an alarm — more like the purr of a cat determined to stay just within the legal definition of silence.

“Do you hear that?” Nora asked Father Donnelly, who had volunteered to stand beside the blossoms and radiate moral approval.

“Hear what, Nora?”

“Exactly,” she said, and they both smiled because the absence of a thing can be as loud as its presence if you give it room.

That night, rain came through like a traveling auntie — over-bright, over-generous, in a great hurry to drench you with attention. Drops stitched themselves into the road, bounced off the butcher’s window, hammered McKeever’s sign until even the gold leaf looked newly baptized. The flowers shone under it, the pink deeper and stranger, as if the rain were revealing their true shade rather than washing anything away.

In bedrooms up and down Tullow, people slept badly and dreamed well. Brendan dreamed he was walking down Main Street with a wedding cake the size of a small lorry, and every time he tried to put it down, it grew another tier and started humming something like a waltz. Mrs. Molloy dreamed she was sixteen again, whirling on the parish hall floor with a boy whose face had escaped her long ago but whose laugh she would have known in a hurricane. Councillor Byrne dreamed of a ribbon-cutting so perfect that the ribbon itself clapped.

Tommy dreamed of nothing, which was a blessing. Mayo chased rabbits in his sleep and caught none of them, which was perfect.

The rain eased, and in the thick dark just before dawn the flowers tilted their faces — if flowers have faces — toward the line of the river and then upward to where the cloud cover broke. For a minute and thirty seconds, every blossom in Tullow seemed to listen to something far above the square, the van, the ditch, the pub, the priest, the butcher, the dog, the whole small stubborn town. Then the listening ended, and the blossoms stood straighter, as if agreeing among themselves.

On Sunday morning, the bell rope at the church stuck fast for a second before Father Donnelly’s tug freed it. He wiped his palms on his cassock and told himself that ropes do that when it’s damp. He told himself many ordinary things in a steady voice, and each one was true, and the truth, while comforting, sat like a buttoned collar on his throat.

He opened the front doors, and the congregation breathed in as one animal.

The steps were framed. Not smothered, not obstructed. Framed, as though by a careful hand. A dozen pink flowers on either side, spaced perfectly, each at the same height, each nodding with the exact solemnity of a choirboy who has been told his auntie is watching.

“Lovely bit of God’s handiwork,” Father Donnelly said aloud because it was his job to say such things. Underneath, at a frequency even his own conscience barely heard, he added: And if You didn’t do it, Lord, I’d be obliged to learn who did.

Nora linked her arm through his on the way in. “It’s a sign,” she whispered.

“It always is,” he said, and smiled the small, bright smile of a man polishing his faith with the hem of his sleeve.

Behind them, a child paused at the threshold and reached one careful finger toward a petal. The petal didn’t move. The air seemed to thicken around the fingertip, very slightly, the way air does near the glass of an aquarium, where you know something is living on the other side of what looks like nothing.

The child withdrew his hand and looked up at his mother. “It’s listening,” he said.

“Don’t be daft,” she replied, and hustled him in, and said a quick prayer for being unkind to the truth when it showed up wearing a child’s voice.

By Sunday night, Tullow agreed on three things:

- The pink flowers were fierce pretty.

- They brightened the place.

- Whoever was planting them had great taste and should keep it up.

The possibility that nobody was planting them sat down quietly in the back of the hall and waited its turn to speak.

Outside, under a sky scrubbed clean by rain, under the stubborn low stars that had watched worse and kinder things, the blossoms exhaled their sweet, exact perfume into the town that had decided, for now, to be charmed.

They were not in a hurry.

They had all the time in the world.

CONTD

Chapter Two — The Spread

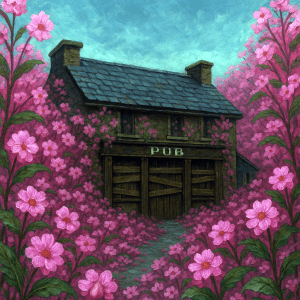

By the second week, Tullow looked as if someone had shaken a giant pot of pink confetti over it and forgotten to sweep up.

It was subtle at first — just the odd extra blossom here, another there — but by Friday morning the plants had developed what you might call a decorator’s eye. They weren’t simply popping up anywhere; they were placing themselves. One had emerged directly in the middle of a chipped flagstone outside McKeever’s Pub, filling the gap perfectly. Another had draped itself like a garland along the top rail of the bridge over the Slaney, each bloom exactly equidistant from the next, as if an invisible florist was very fond of measuring tape.

Main Street Morning

At half past nine on Monday, Mrs. Molloy emerged from her café carrying the week’s deliveries: a crate of milk, a bag of flour, and an entirely unsolicited bouquet of the pink flowers blooming up the back step.

She stopped.

“Well now,” she said, in the voice of someone whose cat had brought home a pheasant and was currently pretending not to know it was there.

When she mentioned it to Brendan Kavanagh, who was wheeling a trolley-load of meat from his van, he shrugged. “Nature finds a way.”

“That’s the sort of thing they say before a dinosaur eats the tourists,” Mrs. Molloy pointed out.

Brendan grinned. “Sure, there’s no harm in it. Besides, I heard Councillor Byrne’s on about making them the town emblem.”

The Initiative

Byrne, as it happened, was in the hardware shop at that moment, ordering “those nice wooden signs” to replace the peeling Welcome to Tullow boards. He wanted the new ones to read:

TULLOW — THE BLOSSOMING TOWN

Come for the flowers, stay for the craic

“It’s a gift from God,” Byrne told the shopkeeper. “You don’t just pull up a gift from God. You put a bench beside it and tell people to take a photo.”

From the corner, Seán O’Malley muttered, “Weeds are a gift from God too, but you don’t see anyone knitting scarves for the dandelions.”

Byrne ignored him. “We’ll get on the tourist map, you’ll see. People will drive here just to smell them.”

The Smell

That smell was becoming harder to ignore. It was everywhere now — thick, sugary, almost fizzy in the nose. Some described it as strawberries and cream; others, like cheap perfume worn without mercy.

In the post office, Mrs. Hession swore it was making her dizzy. “I went to lick a stamp yesterday and I could taste it,” she complained. “That’s not natural.”

Father Donnelly, queueing for his pension, offered that perhaps it was “a seasonal blessing”.

“If it’s a blessing, Father, why does it make me want to sneeze out my brain?”

Uncooperative Behaviour

The plants had begun to show a certain… stubbornness.

When Seán tried to pull one up from the verge outside his driveway, it didn’t snap or tear. It leaned, as if going with him for a moment, and then somehow wasn’t in his hand anymore. He tried again. Same result. The blossom still swayed in the breeze afterwards, unbothered, as though it had watched him attempt a card trick and found it amateurish.

At the Credit Union, the new cleaner refused to “deal with the thing” growing from the carpet under the teller’s desk. “I’m not hoovering around it,” she said. “It’s looking at me.”

The Bridge Incident

On Thursday, two of the older schoolboys decided to test the “fancy flowers” by throwing rocks at them from the bridge.

They managed three hits before a passing bee — large enough that it might have been paid to act as security — dive-bombed them with such accuracy that both dropped their stones and ran for it, swatting at their heads.

“Bee stung me right on the thought,” claimed the taller boy afterwards, pointing to the crown of his head.

Market Square Evening

By the end of the month, Market Square was ringed in pink. The benches looked like they’d been installed for a royal garden party. Couples strolled, children played, and the flowers… well, they were simply there.

“Like they own the place,” muttered Mrs. Doyle from McKeever’s doorway. She’d started wiping down the bar three times more than necessary since the blooms reached her corner. “And everyone’s acting like they do.”

Nora Dowling leaned beside her. “They brighten things up.”

Mrs. Doyle shot her a look. “So would a lick of paint, but you wouldn’t let it crawl up the side of your house while you slept.”

That night, under a half-moon, the flowers along Main Street tilted — all at once, in perfect unison — toward the same unseen point in the sky. No one saw it. No one noticed.

In Tullow, things like that had a way of waiting until no one was looking.

Chapter Three – The Denial

By mid-June, even the least observant in Tullow had to admit the flowers were everywhere. Not in the poetic sense — literally everywhere. They had scaled the bell tower, lined the gutters of every house, and arranged themselves in thick garlands over shopfronts like bunting for a festival nobody had agreed to hold.

The problem was, it was hard to complain when the town looked… well, gorgeous. If you squinted just right, Main Street could have been a postcard from some enchanted village in the Alps, the sort that charges €9 for a coffee and gets away with it.

Byrne’s Vision

Councillor Byrne was thriving.

The Tullow Gazette ran a front-page photo of him standing in front of the Credit Union, its windows framed with perfectly symmetrical pink blooms, under the headline:

“BLOSSOMS PUT TULLOW ON THE MAP”

Byrne had written the headline himself.

At a council meeting, he announced plans for the First Annual Tullow Blossom Festival — a weekend of live music, craft stalls, and a competition for “Best Use of Floral Display in a Domestic Setting.”

Seán O’Malley asked if perhaps they should get a botanist in first, “just to check they aren’t poisonous, invasive, or… y’know… evil.”

Byrne waved him off. “Invasive? They’re not weeds, Seán. They’re pink.”

Excuses, Excuses

The town had already developed a repertoire of excuses for the flowers:

- The Climate Shift Theory — “It’s the mild winters. We’re practically Mediterranean now.”

- The Good Luck Charm — “Haven’t you noticed? Business is up. Tourists are stopping. That’s the flowers, so it is.”

- The Harmless Visitor — “It’s like swallows nesting in the eaves. You wouldn’t knock them down.”

Mrs. Molloy added her own: “If it was dangerous, the dog would know.” (This was despite Mayo, Tommy Doran’s dog, spending most of his day asleep under the table.)

Signs They Ignored

The blossoms were changing, though few admitted it aloud.

The scent had deepened — not just sweet now, but rich, almost thick, like syrup on a hot day. People found themselves standing still without meaning to, breathing it in. A few swore they heard faint music in it, just at the edge of hearing.

The stems had grown stronger, more rope-like. A child swinging on one outside the school discovered it could hold her weight without so much as a creak.

At night, Tommy Doran noticed, the flowers didn’t just close up like normal blooms. They shifted, all of them, to face the same direction — skyward. It made him uneasy in a way he couldn’t name, so he didn’t name it.

A Close Call

One Thursday morning, Seán’s van refused to start. He lifted the bonnet and found the entire engine bay cradled in a nest of vines, each topped with an open bloom, all breathing their scent into the metal.

He fetched the shears and cut them away. By the next morning, they had grown back — thicker, tighter, as if they were holding the engine.

When he told this story in McKeever’s that night, Ned Doyle raised his pint and said, “You see a problem, Seán. I see free anti-theft technology.”

Mrs. Doyle’s Stand

Only Mrs. Doyle at the pub seemed immune to the pink’s charm.

“I don’t trust anything that turns up uninvited and makes itself at home,” she said, pulling pints. “That’s how my brother’s second wife started.”

She had trimmed back every blossom that tried to creep under the pub’s eaves. Somehow, they never grew on the walls for long — though she wouldn’t say what she did with the cuttings.

The Collective Shrug

By the end of June, the whole town was scented and blooming. Tourists took photos. Locals took pride.

If someone pointed out that the post office door now needed shouldering open because of the vines, the reply was a shrug. If anyone wondered why the schoolyard was filling at ankle-height with creeping stems, the answer was a laugh and a “Sure, the kids love it.”

And if a certain hum began to rise in the night air — low, steady, and almost like breathing — well, that was just the wind in the flowers.

Wasn’t it?

Chapter Four – The Pods

The first pod appeared outside Mrs. Molloy’s café on the third Monday of July, hanging from a blossom like a bauble on an overenthusiastic Christmas tree.

It was about the size of a hen’s egg, smooth and glossy, the same pink as the petals but shot through with faint, pearly lines. It looked as if it had been hand-painted by someone with a fondness for fine china and a slightly sinister imagination.

By Tuesday there were two more, one on either side of the doorway. By Wednesday, they were dangling from lampposts, curling under shop signs, even swinging gently from the drainpipe of the Garda station.

The Beat

Tommy Doran swore he could hear them thumping.

Not loud — nothing you’d notice in a room full of chat — but if you stood still near one, there it was: thump-thump… thump-thump, slow and steady, like a heart that had no intention of hurrying.

“Could be the heat,” Brendan Kavanagh suggested when Tommy told him. “Your ears swell up in warm weather.”

“It’s not my ears,” Tommy said. “It’s the things. They’re alive.”

“Everything’s alive,” Brendan replied, which sounded profound but was just a way of ending the conversation before it got weird.

Byrne’s Press Release

Councillor Byrne was now referring to the pods as “seed jewels” in interviews.

“They’re the plant’s way of giving back,” he told the Tullow Gazette. “Imagine the beauty next spring when these… ah… distribute themselves.”

“Distribute themselves how?” the reporter asked.

Byrne blinked. “Well… nature finds a way.”

It was the sort of answer that sounds like wisdom until you think about it for more than four seconds.

Patsy’s Theory

Over a pint in McKeever’s, Patsy announced he knew exactly what the pods were.

“Fruit,” he said confidently. “We’ll be eating them by Christmas. Probably taste like strawberries.”

“They look like they’d taste like soap,” Mrs. Doyle said.

“Soap’s edible in the right light,” Patsy replied, which got him a swift kick under the table from Nora Dowling.

A Market Day Incident

The first pod split open on a Thursday morning, right in the middle of Market Square.

It happened so quietly that most people didn’t notice until the puff of pink dust drifted across the bread stall. Those who inhaled it paused mid-sentence, smiled a slow, dreamy smile, and began walking.

They didn’t answer when spoken to. They didn’t look left or right. They stepped into the thickest clumps of blossoms and vanished from view, like children slipping into tall summer grass.

A few people laughed nervously. “Probably just a faint,” someone suggested. “Hot day.” But the ones who had gone in didn’t come back out. Not that afternoon. Not at all.

Still, the Denial

By the following morning, the official explanation was that “no one had really gone missing, they’d just gone home the scenic way.”

Even the Gardaí agreed, mostly because it was easier than trying to get through the blossoms with the little folding saw from the patrol car’s boot.

And so life in Tullow went on — with pods hanging from every arch and doorway, pulsing softly in the warm July air, as if counting down to something only they knew about.

CONTD

Chapter Five – The First Bloom

It was a Thursday — market day — when the first pod burst.

The square was busy: stalls sagging with potatoes, pyramids of cabbages, stacks of scones under clingfilm. The smell of frying sausages mingled with the ever-present floral perfume, which was now so thick it felt like you could chew it.

A pod hung from the lamppost beside Mrs. Molloy’s tea stall. She’d been keeping one eye on it all morning, more from unease than curiosity. It swayed gently though there was no wind.

At precisely 11:17 a.m., it split.

The sound was small — a damp pop — but enough to turn heads. From the crack in its shell spilled a cloud of shimmering pink dust, catching the sunlight as it drifted across the bread stall and into the crowd.

The Smile

Those who breathed it in stopped mid-step.

Their expressions softened into identical, slow, blissful smiles — the kind you might wear if you’d just been told a secret too beautiful to repeat. Then they began walking, in perfect calm, toward the thickest mass of blossoms at the far side of the square.

“Hey! Where are you going?” called Brendan Kavanagh, stepping in front of them.

They didn’t answer. They didn’t blink. They simply stepped around him and into the flowers, parting the stems without effort, vanishing as if they’d melted into the pink.

Aftermath

The witnesses stood there, stunned. Then came the muttering.

“Maybe they fainted.”

“They’ve gone home the back way.”

“It’s just the heat.”

Within half an hour, the story had been smoothed into something explainable: nothing had really happened, and if it had, it wasn’t serious.

Mrs. Doyle was unimpressed. “People don’t just walk into a hedge and disappear,” she snapped in McKeever’s that evening. “Not unless the hedge wants them.”

“Maybe it’s like Lourdes,” said Patsy. “A spiritual calling.”

“Then why don’t they come back healed?” Mrs. Doyle shot back. “Or at all?”

The Humming

That night, Tommy Doran stood at his gate and listened.

The flowers were humming. Not like bees. Not like wind. A deep, steady tone you could feel in your bones. The pods were larger now, and he could see faint movements inside them — shadows shifting as though something was testing the shell.

Mayo whimpered and went inside.

The Official Line

The next morning, Councillor Byrne addressed the town via a note taped to the Credit Union door:

Please don’t panic. The blossoms and their seed pods are part of a natural cycle. We are blessed to witness it. Enjoy the beauty — and remember: tourism is our friend.

Someone had scrawled underneath in biro:

What if the flowers aren’t?

By Saturday, more pods had split. More people had walked calmly into the blossoms and not returned.

And still, the hum went on.

Chapter Six – The Lock-In

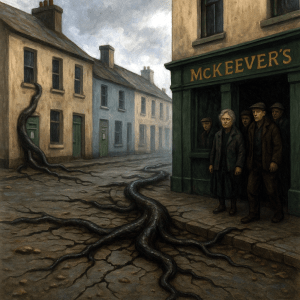

By the third week of July, Tullow was quieter than it had ever been.

The shops were still open — technically — but you had to shoulder through thick curtains of blossoms to get in, and most of the shopkeepers now kept the blinds down so they didn’t have to watch the pods sway outside. The hum in the air was louder.

And the pub had become the last stronghold.

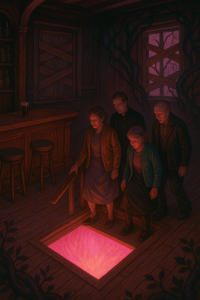

The Fortress of McKeever’s

Mrs. Doyle had always prided herself on running a tight ship, but now she was running a sealed one. The windows had been boarded up with whatever could be found — plywood, old doors, a table top from the darts corner.

Every gap was stuffed with rags and duct tape. The front door was bolted from the inside with a pair of heavy steel bars “borrowed” from the GAA shed.

“Not opening for anyone,” she told the regulars as she poured pints with her usual precision. “If they want a drink, they can grow their own Guinness.”

The Last Regulars

By now, the clientele was down to seven.

- Ned Doyle (no relation to Mrs. Doyle) — convinced the flowers were “only defending themselves.”

- Patsy — convinced they were “trying to communicate” and possibly “open a branch of themselves abroad.”

- Nora Dowling — knitting with fierce determination “in case blankets are needed for whatever’s coming.”

- Seán O’Malley — muttering darkly about “engine trouble of the human variety.”

- Father Donnelly — refusing to take off his overcoat, “in case I’m called to perform an outdoor sacrament.”

- Tommy Doran — who mostly stared into his pint like it might give him a straight answer.

- And Mrs. Doyle, who poured, watched, and listened.

The Incident

It happened just after eight on Friday night.

Something — or someone — thumped against the door. Once. Twice. Then came a dragging sound along the boards.

Ned got up, muttering about “welcoming whoever it is.” Mrs. Doyle blocked him with one arm and hissed, “Sit.”

Through the narrowest crack in the boards, they saw… a man. Or the outline of one. His face was serene, smiling that same dreamy smile as the others who’d walked into the blossoms. His clothes were covered in petals, his hair tangled with vine tendrils that seemed to move in the still air.

He put a hand — pale, petal-dusted — against the door. The vines wrapped around his wrist, curling down from above like living rope.

Then he leaned close, and from his mouth spilled a puff of pink dust that drifted through the tiniest gaps in the boards.

The Breathing Room

It was Nora who noticed first. “Close your mouths,” she snapped.

But it was too late. The dust hung in the air like glitter in sunlight. It smelled sweet, sweeter than ever. For a moment, they all just sat there, breathing in the scent.

Mrs. Doyle slammed a damp tea towel over her nose and barked, “Windows. Tape. Now!”

By the time they’d resealed the gaps, the man outside was gone. Only the vines remained, curling and swaying against the wood, tapping now and then as if checking for weak points.

The Realisation

Later, when the room had gone quiet except for the hum, Father Donnelly spoke.

“It’s not trying to get in,” he said softly. “It’s trying to get us to come out.”

No one argued. No one touched their pint.

And for the first time, even Patsy didn’t have a theory that made it all sound harmless.

CONTD

Chapter Seven – The Waiting

By the end of July, Tullow was gone.

Not in the way that’s counted on maps — the buildings still stood, the river still bent around the bridge, the road signs still pointed to Carlow and Bunclody. But everything was smothered under the pink.

From the air — not that there were many flights now — the town looked like an island of petals in a green sea. Thick swells of blossoms rolled over rooftops and across streets, rising and falling like the backs of great sleeping beasts.

Inside McKeever’s

The pub still held.

Mrs. Doyle kept the stout flowing, though the kegs were getting lighter. The air inside was thick with the smell of hops, damp wood, and the faintest sweetness from outside, sneaking in no matter how they sealed the cracks.

The seven regulars sat mostly in silence now. Conversation had dwindled into murmurs, mutters, and the occasional sharp laugh that nobody found funny. The hum outside was louder than ever — steady, pulsing, as if the whole town had become a single living thing.

The Knock

It came just after midnight.

Not the dull thud from before, but a slow, deliberate tapping on the boarded window nearest the bar.

Tap… tap… tap.

They all froze. Mrs. Doyle set her glass down carefully, eyes never leaving the window.

Then came the voice.

Soft. Warm. Familiar.

“Ned… it’s me. Let me in.”

Ned’s pint wobbled in his hand. It was his sister’s voice — and she’d been one of the first to vanish into the flowers.

“You’re not her,” Mrs. Doyle said flatly.

A pause. Then the voice again, softer still: “It’s better out here. We’re waiting for you.”

The Tilt

In the morning, Tommy risked a look through a narrow gap in the boards.

The blossoms had changed position. Every single one in sight was tilted toward the pub, petals open, pods swaying slightly, as if listening. The stems seemed thicker now, and in some places they’d woven together, forming archways over the street.

“They’re watching us,” he said, pulling back.

“Not watching,” said Father Donnelly. “Calling.”

Nora’s Dream

That night, Nora woke screaming. She said she’d dreamed of the pub filling with petals, pouring in through the windows and doors until there was no room left to breathe — but in the dream, she hadn’t wanted to breathe. She’d wanted to go with them.

“It felt… kind,” she whispered. “Like home.”

No one slept well after that.

The Long Game

The flowers didn’t rush.

They didn’t try to batter down the doors. They didn’t squeeze through the gaps. They simply stayed. Growing. Humming. Waiting.

By the second week of August, the street outside was unrecognisable — a tunnel of blossoms, leading away in both directions. No wind moved there. No birds passed overhead.

And each night, as the moon rose, the entire town of flowers tilted upward, facing the sky in perfect unison… as if waiting for something else to arrive.

Mrs. Doyle stood at the bar one evening, listening to the hum through the walls.

“They’ll wait forever if they have to,” she said quietly.

Behind her, Tommy answered without looking up:

“So will we.”

The hum went on.

Chapter Eight – What Comes Next

The first real storm of the summer came in mid-August.

Not the usual Carlow drizzle dressed up as weather, but a proper, window-rattling, roof-tile-loosening tempest. Rain hammered the boarded pub. The wind roared down the street, rattling loose gutters and tearing branches from the trees on the outskirts of town.

And the flowers didn’t move.

Unshaken

From inside McKeever’s, the seven of them watched through knotholes and hairline cracks in the boards. Outside, the blossoms stood as straight and calm as if the night were still. Rain sluiced off their petals without darkening them. The stems didn’t sway. The pods hung steady, pulsing faintly in the lightning flashes.

“It’s like the wind’s afraid of them,” Tommy muttered.

“No,” said Father Donnelly quietly. “It’s like they’re not part of the world anymore. Or we’re not.”

The Visitors

Near midnight, shapes began to move along the flower-lined street.

At first they looked like people — maybe neighbours, maybe strangers. But their walk was too smooth, too in-step. Each one wore the same serene smile. Each one was laced through with vines, their wrists and necks encircled, petals blooming from their shoulders and hair.

They stopped outside the pub and stood there, unmoving, the rain pooling around their feet.

Every few minutes, one of them would speak.

“Come out.”

“It’s better.”

“You don’t need to be afraid anymore.”

The voices were familiar. Too familiar. Byrne. Mrs. Molloy. The postman. Children from the school. All sounding like they’d swallowed the same warm, honeyed song.

The Sky

On the third night of the storm, it happened.

The flowers, the pods, even the vine-wrapped figures outside — they all turned, together, to face upward.

Through the cracks in the boards, the holdouts saw it: a point of light, far brighter than any star, growing larger by the second. It pulsed in perfect time with the pods.

“What is it?” whispered Nora.

“Whatever they’ve been waiting for,” said Mrs. Doyle.

The Realisation

As the light swelled, the hum deepened until it rattled in their teeth.

Tommy pressed his hands over his ears. “If it’s been waiting for them… maybe it’s been waiting for us too.”

Mrs. Doyle poured herself a measure of whiskey, neat. “Then we’ll decide when it knocks,” she said.

The Last Look

Through a gap no wider than a coin, Father Donnelly saw the light break the clouds. It wasn’t a ship. It wasn’t a sun.

It was… another flower.

Vast. Pink. Beautiful. Descending.

The hum became a roar.

And in the dark of McKeever’s, with the boards shuddering under something far larger than wind, nobody spoke.

Nobody moved.

They just waited.

Chapter Nine – The Blooming Sky

The light over Tullow grew brighter each night.

It wasn’t like the sun — too pink, too alive. Not like the moon — too close, too intent. It was the colour of the blossoms themselves, and when it pulsed, every pod in town pulsed with it, as if they shared the same heartbeat.

Inside the Pub

They had stopped speaking in full sentences. Every word seemed to echo the hum outside, every thought drawn toward that light.

Patsy, who’d once been the pub’s loudest voice, now sat in the corner staring at the boards, lips moving silently. Nora knitted without looking at the needles, her eyes fixed on the faint glow seeping through the cracks.

Tommy had taken to pacing — three steps one way, three steps back — as if walking was the only thing keeping him from… drifting.

The Change in the Air

On the fifth night, the air inside McKeever’s shifted. It was warmer, thicker. Breathing felt like sipping steam from a kettle, only sweet — so sweet you wanted to keep breathing it forever.

Seán O’Malley swore the scent was telling him something. “It’s… it’s instructions,” he whispered. “We’re supposed to join them before it arrives.”

Mrs. Doyle’s reply was sharp enough to cut the air in two. “Then it’ll have to knock harder. Sit down, Seán.”

The Sky Opens

They first saw it through a knothole in the boarded door.

The point of light above had split open. From its centre poured streamers of pink fire — or was it petals? — cascading slowly toward the earth. The blossoms on the ground swayed in rhythm, their pods vibrating in time with each pulse.

The vine-wrapped townsfolk outside raised their arms to the sky, as one.

And then the sound began — not the low hum they’d grown used to, but a vast, ringing tone, layered with whispers that were almost voices.

Tommy’s Mistake

It was Tommy who broke.

Maybe it was the smell, maybe the sound, maybe the months of staring into his pint for answers that never came. He unbolted the door before anyone could stop him.

The moment the gap opened, a rush of warm, petal-scented air flooded in. It wasn’t just air — it felt like hands, coaxing, guiding.

Tommy stepped out into it.

No one followed. Not yet.

The Last Few

They slammed the door shut and barred it again, but the smell lingered. Outside, they could hear Tommy laughing softly, the same slow, blissful laugh they’d heard from the others.

Patsy got up and stood by the boards, one hand pressed to the wood, as if listening.

Mrs. Doyle poured herself another whiskey and said, “It’s going to get in eventually. The question is — will we still be ourselves when it does?”

The hum from the sky swelled.

No one had an answer.

Chapter Ten – Petals Fall

The great blossom in the sky hung over Tullow for three days.

It didn’t rise or set. It simply was, radiating that pink light that softened every shadow and made even the boarded-up windows of McKeever’s glow like stained glass.

On the fourth morning, it began to shed.

The Rain of Petals

They didn’t fall like leaves. They drifted in slow spirals, each one the size of a hand, glowing faintly. The moment they touched the ground, they dissolved into mist, curling into the air before sinking into the soil.

The blossoms on the ground drank it in. You could see them swell, petals deepening in colour, pods quivering with a new urgency.

“They’re feeding,” Seán said, voice flat.

The Whisper

That night, the hum changed.

It wasn’t a single note anymore. It was many — woven together, like a choir that had been practising for years and now knew every line of the song. Beneath it, if you listened too closely, there were whispers.

Names.

Each of the seven inside McKeever’s heard their own name in the hum, soft and steady, repeated over and over.

Patsy began to cry without realising it.

The First Step

At dawn, the vine-wrapped townsfolk outside began to move. Not wandering aimlessly now, but walking in a slow, deliberate procession toward the river. The flowers parted for them, making a corridor of pink leading to the bridge.

In the distance, the sky-blossom pulsed brighter, as if approving.

“They’re leaving,” Nora whispered.

“No,” Mrs. Doyle said. “They’re going somewhere.”

Tommy’s Return

On the second day of the procession, Tommy came back.

He didn’t knock. He just appeared outside the pub, standing in the glow, smiling that slow, endless smile. The vines around his arms and shoulders were thicker now, blooming as he breathed.

“You don’t need to be afraid,” he said, his voice calm and warm. “It’s not the end. It’s… the beginning.”

No one moved to unbar the door.

The Last Night

That night, the petals fell thicker. They stuck to the boards, to the roof, to the very air, until it felt like the pub was floating in a pink fog. The whispers grew louder.

The seven inside didn’t speak. They barely moved.

When dawn came, the petals were gone. So was the great blossom in the sky. The street outside was empty — no flowers, no townsfolk, nothing but the quiet hiss of the river.

Tullow was still there. But it was… bare.

Mrs. Doyle poured the last of the stout into seven chipped glasses. “If it’s the beginning,” she said, “I wonder what it was the end of.”

No one answered.

Outside, in the soil where the blossoms had been, something shifted.

It was only a matter of time.

Chapter Eleven – Roots

The petals were gone by morning.

The streets were bare again, the air oddly cool after weeks of pink warmth. McKeever’s stood in a brittle silence broken only by the creak of the bar’s old timbers.

It should have felt like relief.

It didn’t.

The Quiet Town

They ventured out just after midday.

The flowers were gone — every vine, every blossom, every pod. It was as if the invasion had never happened, except for the hollow, flattened earth where the plants had been thickest.

The buildings stood unchanged, but the paint looked duller, the brickwork older. The whole place felt… drained.

Seán bent down to touch the bare soil in front of the pub. It was warm.

Too warm.

The First Tremor

That night, the hum came back.

It wasn’t in the air this time. It was underfoot. Faint vibrations shivered through the floorboards, making pint glasses tremble on the bar.

Nora pressed her ear to the wood. “It’s deeper,” she said. “Like it’s under us now.”

The Roots

Two days later, they found the first one.

A root, thick as a man’s arm, pushing up through the cracked tarmac at the corner of Bridge Street. It wasn’t pink anymore — it was dark, slick, and glistening wet, as though it had just been pulled from a riverbed.

It moved when they touched it. Slowly. Almost shyly.

By sundown, more roots had appeared — curling out of drains, splitting the mortar between cobblestones, even breaking through the old stone floor of the church.

The Return

On the third night, Tommy’s voice came again from outside the pub.

“You’ve been invited,” he called softly. “Don’t keep it waiting.”

No one unbarred the door.

But in the silence that followed, they all heard it — the faint, steady sound of something burrowing deeper.

Not going away.

Spreading.

The Realisation

In the small hours, Mrs. Doyle poured herself the last whiskey from the bottle and said, “It’s not about the flowers. Never was. They were just the surface.”

She tapped the floor with the toe of her boot.

“It’s the roots you have to worry about. And they don’t let go.”

The hum rose again from beneath, slow and certain, as if in agreement.

Chapter Twelve – Under Tullow

The roots grew fast.

By the end of the week, they’d cracked the pavement in a dozen places and pushed up through cellar floors. They coiled around lampposts and hugged the foundations of houses, always slick, always warm to the touch.

And they were listening.

The First Sound Below

One night, just after closing the shutters, Nora swore she heard a voice from under the floor. Not a whisper — a proper voice, speaking slowly, as if it was learning how.

She leaned closer to the boards, heart hammering.

“Down… here…” it said.

When she told the others, Mrs. Doyle’s only answer was: “Stop listening.”

The Old Tunnels

Father Donnelly knew the church’s foundations better than anyone. He also knew about the old smugglers’ tunnels that ran under the river and half the town — narrow, twisting stone passages long since sealed.

Except now, they weren’t sealed.

Roots had punched through the mortar, curling along the ceilings and walls, vanishing into blackness. The air down there was damp and heavy with the sweet scent they thought they’d left behind with the petals.

The Pull

It began subtly. A thought here. A dream there. Each of the seven in McKeever’s started waking with the same feeling — that they’d been walking all night in darkness, following something just out of sight, always downward.

Some mornings, their boots were wet.

Tommy’s Warning

Tommy came again, this time not smiling.

“You can’t stay up here forever,” he said through the boards. “It’s patient. It’s already under you. When it calls, you’ll answer. That’s how it works.”

Seán swore and hurled his empty glass at the door. It bounced off harmlessly, but the roots outside shivered, as if amused.

The Decision

Mrs. Doyle said nothing until the others were asleep. Then she stood in the middle of the bar, listening to the steady hum rising from below.

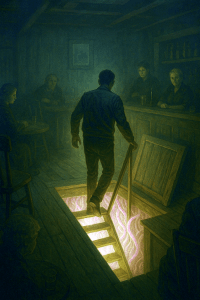

She opened the trapdoor to the cellar and stood at the top of the steps. The scent was stronger there, the air warmer, the hum almost a lullaby.

She didn’t go down. Not yet.

But she didn’t close the trapdoor either.

Chapter Thirteen – The Descent

By September, the ground under Tullow was no longer still.

Some nights, you could feel a slow, rolling movement beneath your feet — like a deep, lazy tide shifting far below. The roots had widened the cracks in the streets, and in the silence after dark, you could hear the soil settling, almost sighing.

The Trapdoor

The open cellar trapdoor had become the centre of the pub. Nobody talked about it, but they all noticed how often they drifted near it without meaning to.

From below came the scent — stronger now, richer — mixed with the low hum that seemed to vibrate inside their bones.

Once, Nora swore she heard laughter down there. Not cruel. Not mocking. Just… pleased.

The First to Go

It was Seán who went first.

One evening, while Mrs. Doyle was fetching bottles from the back, he simply walked to the trapdoor and started down. Nora caught sight of him halfway, one hand on the wall, his face serene in the glow rising from below.

By the time she called out, he was gone.

No one followed. No one tried.

The Change Above

The next morning, the town felt different.

The air was warmer again, the scent thicker. The roots outside the pub’s walls had shifted — now they were coiled tighter, almost as if they were guarding the building.

And somewhere underfoot, the hum had taken on a rhythm like breathing.

Tommy’s Visit

Tommy returned, this time standing right in the doorway, no vines covering his face.

“You’re holding out,” he said simply. “But it’s not a siege. It’s an invitation. You’ll understand when you see it.”

Patsy stood then, almost without thinking, and took one step toward the door. Mrs. Doyle’s barked “Sit!” snapped her back. But the look in Patsy’s eyes said it wouldn’t be the last time.

Below

That night, Mrs. Doyle dreamed of walking in the tunnels beneath Tullow. The walls were made of roots, warm and damp, and they pulsed gently as she passed. The air was filled with drifting pink motes, and somewhere ahead, in the darkness, something vast and blooming waited for her.

When she woke, her boots were wet.

Chapter Fourteen – The Calling

By mid-September, the hum was no longer background noise.

It was in their sleep.

It was in their speech.

It was in the pauses between heartbeats.

The whole of McKeever’s seemed to breathe with it, the walls shifting ever so slightly, the air warm as a greenhouse. The scent was no longer flowers — it was richer now, darker, like soil turned after rain.

The Dreams

None of them talked about it openly, but they all had the same dreams.

Walking the root-tunnels, barefoot.

The walls parting for them like curtains.

Something waiting ahead — vast, pink, and pulsing in the dark — that whispered their names in a voice that was their own.

When they woke, their boots and socks were damp.

Nora Breaks

It was quiet in the pub that Tuesday afternoon when Nora set her knitting down, stood, and said simply:

“I’m going to see it.”

Mrs. Doyle told her to sit, but there was no sharpness in her voice now — just weariness. Patsy half-rose as if to follow, then sank back down.

Nora walked to the trapdoor, her fingers brushing the wood like it was the door to a friend’s house. She descended without looking back.

The hum swelled when she was gone.

The Pull at the Door

That night, the roots outside shifted again, tightening like muscles. The boards of the pub creaked, not from wind, but from the subtle pressure of something settling in around it.

From far below came a sound like a heartbeat. Slow. Patient.

Tommy’s voice rose through the floor this time, warm and steady:

“Soon.”

The Remaining

Only four remained now — Mrs. Doyle, Patsy, Father Donnelly, and Ned.

They sat in silence, not touching their pints. The hum filled the spaces between them, and the glow from the trapdoor flickered faintly across their faces.

Mrs. Doyle stared into it for a long time, her jaw set.

“It’s not a siege,” she murmured. “It never was. It’s a homecoming.”

No one argued.

Chapter Fifteen – The Last Pour

By the third week of September, the pub felt more like a waiting room than a refuge.

The glow from the trapdoor was stronger now, casting the ceiling in a faint blush, as though the roots themselves were shining upward. The hum had become a constant, gentle pressure inside their skulls — not painful, but impossible to ignore.

The Final Four

Mrs. Doyle polished the same glass for ten minutes before realising she’d been doing it. Patsy sat nearest the trapdoor now, elbows on her knees, listening. Father Donnelly clutched his rosary without moving his lips, and Ned stared into his untouched pint, the stout’s head gone flat hours ago.

No one mentioned the others.

The Knock Below

That night, it came — a soft knock, not at the front door, but from under the trapdoor.

Three slow taps.

Then a pause.

Then, in unison, the voices of everyone who had gone before — Seán, Nora, Tommy, and more — all speaking as one:

“It’s time.”

Mrs. Doyle Decides

She didn’t ask the others. She simply set down her cloth, walked to the trapdoor, and put her hand on it.

“It’s been my bar all my life,” she said, not quite to them, not quite to herself. “But maybe this isn’t leaving it behind. Maybe it’s bringing it with me.”

Without another word, she opened it.

The Descent

The glow rushed upward like a tide, spilling over the floor and painting the walls in warm pink light. The scent was overwhelming — fresh earth, summer rain, and something sweeter, something that made every bone feel lighter.

Mrs. Doyle started down the steps.

Patsy followed before Ned could stop her.

Father Donnelly hesitated, knuckles white on his rosary, then stepped forward too.

Ned Alone

Ned was the last.

He stood in the empty bar, the hum filling the space where voices had been. The trapdoor gaped before him, the glow beckoning.

He drank the last warm mouthful of his pint, set the glass down carefully, and said, “Ah, feck it.”

Then he went down.

The Empty Pub

McKeever’s was silent again.

The trapdoor stood open.

And somewhere far below, in the dark warmth under Tullow, the hum changed — becoming fuller, richer, as if welcoming the last piece it had been waiting for.

Chapter Sixteen – Beneath

The steps were warm underfoot.

Not the damp, cold stone they’d expected from the old cellar, but a soft, pulsing warmth that seemed to keep time with their breathing. As they descended, the scent grew thicker, almost visible in the air — drifting motes of pink that swirled lazily in the glow.

The Tunnel

The cellar was gone.

In its place stretched a root-lined tunnel, the walls curving away into darkness. The roots were as thick as tree trunks, braided and knotted, glowing faintly from within. They moved as the four passed, parting just enough to let them through, then sealing silently behind.

No one spoke. The hum was too loud here — it wasn’t in their ears anymore, but inside their heads, each pulse sending a shiver through their bones.

The First Bloom

They rounded a bend and saw it.

The tunnel opened into a vast cavern lit entirely by a single bloom — enormous, taller than McKeever’s itself, each petal translucent and glowing like stained glass. Its centre pulsed with a slow heartbeat of light, and every root in the chamber was anchored into it, feeding and drinking in equal measure.

Around its base stood the others — Seán, Nora, Tommy, and more — all serene, their skin threaded with fine pink veins, petals blooming from their shoulders and hair.

They turned as one to greet the newcomers.

The Welcome

“It’s been waiting for you,” Tommy said, his voice soft but carrying perfectly.

No one questioned who it was.

The great bloom shifted slightly, its petals opening wider. A rush of warm, perfumed air swept over them, and in it came the feeling of being remembered, of being known completely.

Patsy began to weep, not in fear, but in something close to relief.

The Joining

One by one, they stepped forward.

The air thickened with the hum, now layered with the faint echo of their own heartbeats. As each of them reached the base of the bloom, the roots coiled gently around their ankles, warm and soft, pulling them closer until they disappeared into the mass of petals.

When Mrs. Doyle’s turn came, she looked back once, as though expecting the pub to still be there. Then she smiled and stepped forward.

The Last View

Far above, through the twisting braid of roots, a faint circle of daylight marked where the trapdoor had been. It was smaller now. Fainter.

And then the petals closed, and the light from above was gone.

Chapter Seventeen – The Blooming

Above ground, Tullow was silent.

The streets lay empty, the shop doors ajar, the green post box standing lonely on Main Street. The air was cooler now, and the last of the September rain polished the cobblestones to a mirror sheen.

But underfoot, the hum was stronger than ever.

Beneath the Roots

In the great root-chamber, the bloom had opened fully.

Its petals spread wide in slow, graceful motion, revealing a deep heart of light that shifted through shades of pink and gold. The townsfolk stood in a circle around it, their faces peaceful, eyes half-lidded, breathing in perfect rhythm with the bloom.

Vines now threaded through their limbs, curling around their spines, blooming gently from their skin. They didn’t resist.

They didn’t want to.

The Song

The hum had become a song now — not quite human, not quite alien. It was a melody that seemed older than the soil, curling into every corner of the tunnels and up into the cracks of the streets above.

It was patient.

It was gentle.

And it was calling.

The New Roots

Through the damp earth above, new shoots began to press upward. Not blossoms this time — buds. Small, pale, and tightly furled, waiting for their moment. They pushed through garden beds, cracked the mortar of old walls, crept across the cemetery stones.

No one was there to pull them out.

The Last Visitor

Weeks later, a lone hiker passing through Tullow found the streets empty.

He called out, but no one answered.

When he stepped into McKeever’s, the smell of earth and summer rain hit him so hard he almost staggered. The trapdoor yawned open, and from below came a warm, pink glow — and a sound that was both a hum and a welcome.

The man hesitated only a moment.

Then he smiled faintly, and began to descend.

Epilogue

In the heart of the bloom, new faces turned upward to greet him.

The petals closed again, the roots shifting in slow contentment.

And under Tullow, the song went on.

THE END