Sunbury Days

Sunbury Days

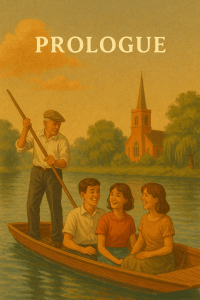

Prologue: The Village by the River

When I close my eyes and think of childhood, it is Sunbury-on-Thames that comes first to mind. Not the Sunbury of today, with its busy roads and rows of new houses, but the Sunbury of the 1960s — smaller, gentler, and more like a village than a suburb. It was a place where the Thames curved lazily past meadows and willows, where church bells drifted across the rooftops on Sunday mornings, and where the whole world seemed contained within a few familiar streets.

Life was simpler then, though we didn’t know it at the time. Neighbours leaned over fences to exchange gossip. Children dashed in and out of each other’s houses as though every home were their own. The corner shop, with its rows of glass jars, seemed to contain more treasure than any palace. Summers stretched out in golden haze, the river glittering at the heart of it all. Winters were marked by frosted windows, steaming coats, and the smell of coal fires in the evening air.

To be a child in Sunbury was to live in a small but endlessly expanding universe. The High Street was our city, the Green our stadium, the towpath our frontier. Each day offered new discoveries — a den to be built, a tree to be climbed, a rumour to be tested. We believed in ghosts at the Mansion, in the magic of lucky bags, in the possibility that our makeshift rafts might one day carry us as far as London.

Most of all, we belonged. Belonged to the street, the school, the river, and to each other. We were held in place by the rhythms of bells, the voices of neighbours, and the certainty that however far we roamed, Sunbury would be waiting when we came back.

Looking back now, I see how small it all was — a handful of streets, a stretch of river, a scattering of people. But to us it was vast, a whole world unfolding at our feet. And in memory, it remains vast still: golden, glowing, a village by the river where childhood stretched as wide as the sky.

Chapter One: School Days

School in Sunbury-on-Thames in the 1960s was a curious mixture of fear, fun, and the faint smell of damp coats and chalk dust. We trudged there in the mornings, satchels slung across our backs, our shoes already scuffed from football in the street. Mothers sent us off with the usual parting cry — “Don’t get into trouble!” — as though trouble were something lying in wait at the school gates, ready to pounce the moment we stepped inside.

Our school building was a squat, brick affair with draughty windows that rattled when the wind blew up the river. The corridors smelt of polish and pencil shavings, and the classrooms had blackboards that always seemed to squeak at the worst possible moment. Ink wells sat in the corners of our wooden desks, and our fingers were perpetually stained blue, no matter how hard we tried to wash them.

Miss Jenkins was my teacher, and to us she seemed ancient, though in truth she was probably only thirty. She had a sharp nose and sharper eyes, and she could silence a rowdy class with a single lift of her eyebrow. She carried a ruler everywhere like a marshal with a six-shooter, rapping it against the desk when we whispered too much. Yet there was something almost motherly in the way she adjusted your collar or slipped a sweet to a child who had scraped a knee in the playground.

The playground itself was where life truly happened. Lessons were something to be endured, but break time — that was freedom. We played British Bulldog until the dinner ladies shouted at us, or marbles on the drain covers until someone lost his prized “tiger eye” and tears had to be suppressed. Conkers dangled from strings in September, each one hardened in vinegar or baked in the oven, despite our mothers’ protests. Boys boasted of their conkers’ “lives,” and fierce battles left shattered shells scattered across the tarmac.

There were pecking orders in the playground, decided not by strength but by ownership of the best toys. The boy who produced a brand-new football instantly became king, surrounded by a crowd of eager courtiers. Hopscotch squares chalked onto the pavement by the girls blurred after the first drizzle, but were always redrawn with fresh energy. Skipping ropes slapped against the ground in rhythm with rhymes that we boys pretended not to listen to, though we secretly envied their easy coordination.

Comic incidents were frequent. Once, a pigeon flew in through an open window during maths, sending half the class diving under their desks. It strutted along the blackboard, leaving a trail of chalk dust on its claws, before Miss Jenkins calmly coaxed it back out with her ruler. Another time, Peter Wilkins hid a frog in his satchel and released it during handwriting practice. The poor creature hopped across the room, sending inkwells flying and splattering blue blotches over our copybooks. Miss Jenkins confiscated the frog, but to our astonishment she released it into the school garden rather than punish Peter. We all looked at her differently after that — perhaps she wasn’t as stern as we thought.

Lunchtimes were another adventure. The smell of boiled cabbage seemed to permeate the hall, mingling with the sharp tang of custard. We queued with metal trays, praying it was jam sponge day rather than tapioca pudding day. No child ever forgot the horror of lumpy tapioca. The dinner ladies were formidable, ladling portions with military precision and glaring at any child who dared leave food uneaten. Many a sprout was hidden under mashed potato or slipped into a pocket when their backs were turned.

And yet, despite the strictness, there was joy. Fridays carried the promise of freedom, with the last bell releasing us into a weekend of football on the Green, fishing by the river, or simply roaming the streets until the streetlights came on. The sense of release as we burst from the school gates was almost intoxicating.

Looking back now, the lessons blur together — the times tables, the handwriting drills, the history dates recited by rote. What remains vivid are the faces of friends, the sound of marbles clicking together, the smell of chalk dust, the sight of Miss Jenkins’ raised eyebrow. School was less about what we learned from the blackboard and more about the friendships forged in the playground, the small victories in conker battles, and the quiet thrill of surviving another day under the watchful eye of the teachers.

Chapter Two: The River

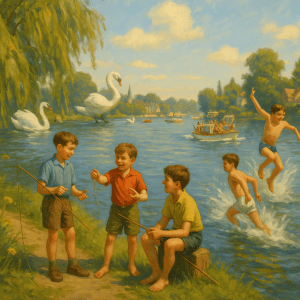

If school was where duty lived, then the river was where freedom began. The Thames was our playground, our frontier, our ocean, and our stage. It flowed past Sunbury-on-Thames as it always had, wide and slow, with willows trailing their branches into the water and swans gliding like monarchs. To adults it was something to be admired at a safe distance. To us, it was an adventure waiting to happen.

We spent entire afternoons along the towpath, armed with fishing lines that owed more to optimism than to craftsmanship. A bit of string tied to a stick, a bent pin for a hook, and maybe a worm dug up from the allotment — that was our tackle. We sat with the solemnity of seasoned anglers, staring into the murky depths, though the only things we ever caught were floating twigs and the occasional boot that had seen better days. “I nearly had one that big!” someone would always claim, spreading their hands wide. We all nodded gravely, understanding that on the river, hope counted for more than proof.

The swans were the true rulers of the Thames. They glided past with disdain, their long necks arched, their eyes sharp as policemen’s. If you dared get too close, they hissed, wings half-opened, and we scattered like rabbits. Once, Billy Hawkins tried to feed one a bit of stale bread. It snatched it from his hand with such force that he toppled into the shallows, flailing and spluttering while the rest of us laughed ourselves breathless.

Boats came and went, each one a source of wonder. There were motorboats that buzzed past, sending waves lapping at our feet, and pleasure cruisers filled with holidaymakers. We waved furiously, and to our delight, they often waved back. Sometimes a radio would be playing — scratchy, tinny, but magical. I still remember the first time I heard Ticket to Ride drifting across the water, the sound mingling with the splash of oars and the cries of gulls. For a moment, the river felt like it was carrying the future downstream, straight from Liverpool.

Swimming was forbidden, which of course made it irresistible. On the hottest days we stripped to our underpants and hurled ourselves into the water with shrieks of delight. The shock of the cold stole our breath, but once in, we felt invincible. We raced from one jetty to another, our arms thrashing, reeds tugging at our legs. There was always a whisper at the back of our minds about weeds that could pull you under, about mysterious currents, but those whispers only added to the thrill. We climbed out afterwards, shivering, goose-pimpled, and triumphant, smelling of river water and freedom.

One summer we decided to build a raft. Between us we collected planks from behind sheds, an old door, and two oil drums we’d rolled half a mile down the lane, much to the annoyance of their rightful owner. We tied the lot together with string, rope, and a prayer, and with great ceremony launched it onto the river. For about twenty glorious seconds it floated. Then the whole contraption wobbled, listed, and collapsed beneath our feet. We floundered back to shore in disgrace, our “Titanic” already drifting downstream in pieces. My mother wasn’t impressed when I squelched into the kitchen, dripping on the linoleum, but secretly I felt proud. We had dared the Thames itself, and that counted for something.

There were quieter moments too. Evenings when we simply sat on the towpath, legs dangling, watching the water turn gold in the setting sun. Barges moved slowly past, their crews calling greetings, the smell of coal smoke and diesel hanging in the air. A dog barked somewhere in the distance, and the world seemed both endless and safe.

The river taught us many things — how to balance on slippery jetties, how to paddle a borrowed canoe without capsizing, how to tell a likely fishing spot from a hopeless one. But more than that, it gave us a sense of belonging. The Thames wasn’t just water flowing past; it was the thread that tied our childhood together, carrying our laughter and secrets downstream, holding them safe in its currents.

Even now, whenever I see the Thames, I can almost hear those echoes — boys shouting, radios crackling, the splash of a doomed raft. And for a moment, I am back there again: ten years old, barefoot, with the whole golden river stretched out before me like a promise.

Chapter Three: Village Characters

Every village has its characters, and Sunbury-on-Thames in the 1960s was no exception. Looking back, it feels as though the streets were peopled not just by neighbours but by figures from a storybook — each one distinct, each one memorable. To a child, they were larger than life.

Mr. Pickering and His Cucumbers

Take Mr. Pickering, for instance. He was the unofficial king of the allotments behind the railway embankment. He wore a flat cap in all weathers and had hands as gnarled as the bean poles he hammered into the soil. He claimed, with great seriousness, that he was on the brink of growing “a cucumber as long as a cricket bat.”

Whenever we passed, he would beckon us over, lifting the leaves of his plants as though revealing crown jewels. We would nod solemnly, stifling our giggles as he compared their length to imaginary bats. Rumour had it he once entered a cucumber into the village fete competition that was so long, it bent like a banana. He insisted the judges had conspired against him when he failed to win first prize. “Jealousy, pure jealousy,” he muttered for months afterwards.

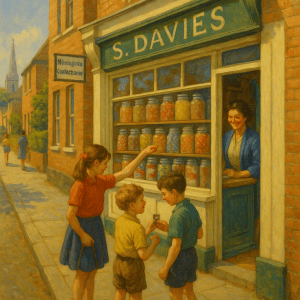

Mrs. Davies of the Sweet Shop

Then there was Mrs. Davies, who ran the sweet shop near the Green. To us she was part magician, part mathematician. She wore horn-rimmed glasses on a chain, and she could add up a jumble of coins faster than any teacher.

We’d pour out our pockets — ha’pennies, farthings, thrupenny bits — and she’d say, without hesitation, “That’ll get you a sherbet fountain, two aniseed balls, and a gobstopper — or one packet of Fruit Salad chews if you’re feeling adventurous.” She always knew exactly how far our money would stretch, and somehow we always left with the best haul possible.

Her shop was an Aladdin’s cave: glass jars lined the shelves, each filled with bright treasures — lemon sherbets, humbugs, chocolate limes, pear drops. She measured them out on brass scales, the sweets clinking into paper bags that grew warm and greasy in our hands. Outside, we sat on the kerb, our tongues turning red or green, convinced we had just touched paradise.

The Postman Who Knew Too Much

Our postman was Mr. Harris, a thin, wiry man with a cap pulled low and legs like a stork’s. He cycled around the village with a red satchel slung over his shoulder, his bell ringing a cheerful “ting-ting.”

But the remarkable thing about Mr. Harris was how much he knew. He could tell you who was expecting a baby before the neighbours had even whispered it, who had written to a cousin in Australia, who had received a letter from the bank. “Morning, Mrs. Clarke,” he’d say, “your sister in Brighton writes that the baby’s cutting teeth.” We children thought he was some kind of magician until we realised he simply read the postcards as he cycled along.

Still, there was something comforting about him. If you were home sick from school, he’d tap on the window and hold up the envelope before slipping it through the letterbox, as if to remind you that the world was still going on outside.

The Ferryman

And then there was George, the ferryman. He looked like he belonged to another century altogether, with his weathered face, heavy boots, and cap pulled low against the wind. He operated the small ferry across the Thames, rowing people from one bank to the other with steady, patient strokes.

We loved to linger near his jetty, listening to his stories. He talked of great floods when the river burst its banks and swans glided down the High Street. He spoke of wartime nights when the river was blacked out, and even the moon seemed to disappear. Whether the tales were true or not didn’t matter. To us, George was a keeper of secrets, a man who had seen things the rest of us could only imagine.

Sometimes, if he was in a good mood, he let us sit in the boat while it rocked gently, our hands trailing in the water. “The Thames has a long memory,” he’d say, “and it never gives up what it wants to keep.” We shivered deliciously at those words, half afraid, half enchanted.

Others We Remember

There were countless others:

-

The milkman, whistling as he clinked bottles onto doorsteps in the early morning.

-

The vicar, whose sermons we endured but whose booming laugh filled the church hall at Christmas parties.

-

The policeman, cycling slowly through the streets, whose very presence kept us from mischief (at least until he turned the corner).

Each one added to the tapestry of village life, their voices and habits as much a part of Sunbury as the tolling bells of St. Mary’s or the slow curve of the river.

Looking back now, it’s these characters I remember most vividly. They were ordinary people, really — shopkeepers, gardeners, postmen — but to a child, they were part of the magic that made the village feel alive. They gave Sunbury its character, its humour, its warmth. And though the years have passed, I can still see them clearly: Mr. Pickering with his cucumbers, Mrs. Davies with her jars of sweets, Mr. Harris ringing his bicycle bell, and George the ferryman, rowing steadily across the timeless Thames.

Chapter Four: Home and Neighbours

If the river was the stage for our adventures, then the street where we lived was the backdrop of daily life. Our road was neither particularly grand nor particularly poor — just an ordinary street of terraced houses and semi-detacheds, with neat front gardens and long back ones where vegetables grew alongside rose bushes. Yet to me, it was the centre of the universe.

The Soundtrack of the Street

Mornings began with the clatter of milk bottles on doorsteps, the whistle of the milkman fading as he rattled his cart away. The postman’s bell followed soon after, and then the rhythmic rumble of prams as mothers wheeled younger children to the shops. Washing machines were still a novelty, so washday was announced by the sight of steam rising from kitchen windows and the smell of soap powder drifting into the street.

By midday, lines of washing fluttered in almost every garden — white sheets billowing like sails, socks pegged in neat rows, shirts dancing in the breeze. There was an unspoken rivalry between neighbours over who managed to get their washing whitest, and heaven help the child who came charging through the garden with muddy hands just as the sheets had been hung out.

Mothers and Gossip

The real life of the street was carried out over garden fences. Our mothers leaned across them, arms folded, aprons still on, exchanging the latest news: who was poorly, whose son had passed the eleven-plus, who was “walking out” with whom. Children learned more by listening to those chats than from any classroom lesson.

Mrs. Clarke from next door had a voice like a foghorn and an opinion on everything. If she wasn’t in her garden, she was at her window, curtain twitching. Once, when our cat dug up her tulips, she stormed round and declared, “That animal should be locked up!” My mother, unflappable as ever, simply offered her a slice of sponge cake, and the quarrel was forgotten. By teatime, Mrs. Clarke was back at the fence, gossiping as if nothing had happened.

Children in and out of Houses

We children drifted in and out of one another’s homes without ceremony. A knock on the back door was enough — or sometimes not even that. We’d be halfway through someone else’s biscuits before their mother realised we weren’t her own. Tea was invariably offered, often consisting of a cup of orange squash and a slice of bread and dripping or jam.

Games spilled from one garden to another. One week it might be cricket with a dustbin lid for a wicket; the next, a new den built out of old crates behind the sheds. Arguments flared and died quickly — usually over whose turn it was to bat, or who had stolen whose conker. By the next day we’d forgotten the row entirely, united again in the search for adventure.

The Comedy of Everyday Life

Of course, everyday life supplied its own comic moments. I remember the day our neighbour, Mr. Wilson, tried to install a television aerial on his roof. The whole street gathered to watch as he clambered about, shouting instructions to his wife, who called back from the garden, “A little more to the left!” The aerial wobbled, Mr. Wilson lost his footing, and down he came, sliding most of the way on his backside. He wasn’t hurt, but his pride suffered, and we children laughed until our stomachs ached.

Or the time Mrs. Clarke’s dog stole a string of sausages straight off her kitchen counter and paraded up the street with them dangling from his mouth like a trophy. Half the neighbours gave chase, but the dog disappeared round the corner, and Mrs. Clarke was still complaining about “that blasted hound” weeks later.

The Comfort of Belonging

For all the squabbles and rivalries, there was comfort in knowing everyone, and in everyone knowing you. If you fell off your bike, half a dozen doors would open to check you were all right. If your father was late home, neighbours would keep an eye out until they saw him turn the corner. Life was lived openly, communally, without the high fences and locked gates of later years.

To me, those gardens, those fences, those neighbours formed the fabric of home. They were ordinary people, leading ordinary lives, but together they created a sense of belonging that was as solid and reassuring as the bricks of our houses.

Even now, when I hear the flap of washing on a line or catch the faint whiff of soap powder, I am carried back to that street in Sunbury, where life played out in gardens and kitchens, where neighbours argued and laughed, and where, for a child, the world felt endlessly secure.

Chapter Five: The Corner Shop

If the river was our playground and the street our stage, then the corner shop was our treasure cave. To step inside was to be transported from the everyday world of chores and homework into a realm where a single penny could open the gates of paradise.

The Shop Itself

The shop was a narrow, dim place, with wooden shelves sagging under tins of condensed milk, packets of biscuits, and boxes of tea. A brass bell tinkled whenever the door opened, and the air smelled of sugar, tobacco, and floor polish. Behind the counter stood Mrs. Davies, in her cardigan and horn-rimmed glasses, presiding over her kingdom like a benevolent queen.

The real marvel, though, was the wall of glass jars — tall cylinders filled with boiled sweets of every colour. Lemon sherbets as bright as sunlight, pear drops glowing pale pink and yellow, striped humbugs, chocolate limes, barley sugar twists. They caught the light like jewels. As a child, I was convinced there was no sight more wonderful in all the world.

The Ritual of Pocket Money

We didn’t rush our purchases. No — going to the shop was a ritual. First came the grand emptying of pockets onto the counter. Out tumbled coins in copper and silver, worn smooth from years of passing through countless hands: ha’pennies, farthings, thrupenny bits. Mrs. Davies would purse her lips, tallying them with uncanny speed.

“Well now,” she’d say, “you’ve sixpence ha’penny. That’ll get you a gobstopper the size of your fist, or a paper bag of liquorice laces, or perhaps two aniseed balls, three fruit salads, and still enough for a penny chew.”

The arithmetic was dizzying. We children stood frozen, torn between the magnificence of a single sherbet fountain or the sheer abundance of a bag filled with smaller sweets. It was, in its way, our first lesson in economics — and in the agony of choice.

The Delights We Chose

There were favourites, of course. Gobstoppers, huge and unyielding, that threatened to crack your jaw if you bit them too soon. Flying saucers, fragile discs filled with sherbet that fizzed on your tongue. Sherbet fountains — liquorice sticks dipped into yellow powder that made us sneeze if we inhaled too sharply.

Some swore by blackjacks and fruit salads, tiny squares that glued your teeth together. Others went for sweet cigarettes — white sticks with pink tips, which made us feel daring as we strutted about puffing them like film stars. The adults disapproved, but secretly we thought they looked rather envious.

And then there was the eternal thrill of the lucky bag. For a penny you got a small paper packet containing a random assortment of sweets and, if you were fortunate, a toy. Most of the toys were useless bits of plastic — a whistle that barely whistled, a tiny spinner that broke within an hour — but the chance of finding treasure kept us hooked.

The Social Hub

The shop was more than just a place for sweets. It was the village hub, where mothers exchanged gossip as they bought bread and sugar, and where children plotted their next adventure. Standing in line, you learned who had the measles, whose uncle was visiting from up north, and who had been spotted cycling down the High Street “without hands on the handlebars, the little show-off.”

Mrs. Davies herself was a fountain of local knowledge. She always seemed to know which child had been kept late at school, which father had a new job, and which mother was planning a surprise birthday cake. We sometimes suspected she knew everything that happened in Sunbury before it actually occurred.

The Walk Home

Leaving the shop, clutching our paper bags, was a moment of pure triumph. We strutted down the street, tearing into our treasures before we’d gone five steps. Tongues turned red, green, or black depending on our choices. We traded chews and compared gobstoppers, declaring with solemnity that this week’s pear drops were “definitely bigger than last week’s.”

By the time we reached home, the sweets were usually gone, the paper bags tucked into pockets as trophies. Mothers scolded us for spoiling our tea, but we didn’t care. For us, the corner shop was more than a place to buy sweets — it was the heart of childhood itself, the little kingdom of delight that kept Sunbury golden.

Even now, if I catch the faint rustle of a paper bag or smell liquorice, I am carried back to that dim, sugary shop, with its tinkling bell, its rows of jars, and the kindly eyes of Mrs. Davies watching as I counted my coins and chose, once again, the taste of magic.

Chapter Six: Sundays

Sundays in Sunbury-on-Thames were unlike any other day of the week. The very air seemed different — slower, softer, filled with the chime of bells and the smell of roast beef drifting from open windows. Even the river appeared to glide more quietly, as though it too had learned the art of keeping the Sabbath.

The Bells of St. Mary’s

The day began with the bells of St. Mary’s. Their sound rolled across the rooftops and gardens, calling the faithful and waking the rest. To us children, they were less a summons than a backdrop: something eternal, marking out time as surely as the passing of the seasons.

Families filed through the lychgate in their Sunday best. Fathers in dark suits, mothers in patterned dresses, children scrubbed and brushed, shoes polished until they shone. We wriggled in the pews, pretending to listen while sneaking glances at friends across the aisle. The vicar’s voice droned on, mingling with the rustle of hymn books and the occasional cough.

For those not in church, Sunday still had its own quiet dignity. Shops were closed, and the High Street dozed in the sunshine, as though wrapped in a blanket of peace.

The Sunday Roast

By midday, the whole village smelled of dinners in progress. Every house seemed to be cooking the same meal: roast beef or lamb, potatoes crisping in the oven, vegetables simmering on the stove. Gravy bubbled in pans, and Yorkshire puddings puffed up like balloons.

Our own table was always laid properly on Sundays — a white cloth, the “good” plates, knives and forks polished until you could see your face in them. Father carved with ceremony, passing slices of beef as though he were dispensing treasure. We children squabbled over who got the crispiest roast potato, while Mother kept order with sharp looks and gentle nudges.

Pudding was custard poured over jam sponge or apple crumble. The taste of hot custard, thick and sweet, is still to me the flavour of Sunday itself.

Afternoon Walks

After dinner, when the washing-up was done and Father had enjoyed his pipe in the garden, we often went for a walk. Sometimes it was along the towpath, past the willows and swans, where the river caught the light like a ribbon of gold. Other times it was across the cricket green, where the crack of bat against ball echoed in the still air.

Father always declared, “A proper Sunday isn’t a proper Sunday without the sound of leather on willow.” He wasn’t much of a cricketer himself, but he knew the rules inside out and offered a running commentary to anyone within earshot. We children half-listened, more interested in catching stray balls and hoping for a turn to bowl.

The Quiet Evening

As the sun dipped low, Sunday slipped into quiet. Radios played softly indoors — the familiar tones of “Sing Something Simple” or the Top 40 countdown. Mothers darned socks or prepared packed lunches, while fathers dozed in armchairs, newspapers spread like blankets.

For us children, there was always a faint dread as evening drew on: the knowledge that Monday meant school. But even that could not spoil the gentle comfort of Sunday night — the smell of polished shoes drying by the fire, the murmur of voices from the front room, the last slice of bread and dripping before bed.

A Day Apart

Looking back, Sundays seem to have belonged to another world entirely. They were slower, simpler, filled with rituals that gave shape to the week. Bells, roasts, cricket, quiet evenings — they wove a rhythm into our childhood that we scarcely noticed at the time.

Today, when Sundays are as busy as any other day, I sometimes close my eyes and remember the stillness of those 1960s afternoons in Sunbury. The bells ringing, the swans gliding, the smell of custard and roast potatoes, and the comforting sense that the world was exactly as it should be.

Chapter Seven: The Summer Fete

If Sundays were quiet and orderly, the summer fete was its glorious opposite: noisy, colourful, and bursting with life. It was the highlight of the year in Sunbury-on-Thames, looked forward to with mounting excitement as June turned into July.

The Build-Up

The fete was always held on the village green, though preparations seemed to spread across the entire parish. Notices went up in the Post Office window weeks in advance: Grand Summer Fete! Raffle! Coconut Shy! Tug-of-War! Children whispered about it in school, speculating over prizes and plotting how to win them. Mothers sewed bunting, fathers hammered together stalls, and everyone seemed to be baking Victoria sponges and rock cakes for the competitions.

On the morning of the fete, the whole village buzzed with energy. Tables were dragged out, marquees were raised, and the air filled with the mingled scents of cut grass, fresh paint, and anticipation.

The Sights and Sounds

By midday, the Green had been transformed into a carnival. Stalls groaned under homemade jams, jars of pickled onions, knitted tea cosies, and piles of second-hand books. The brass band tuned up with much coughing and squeaking before launching into a triumphant march that could be heard all the way down Thames Street.

Children darted about clutching sixpences, their eyes wide at the array of games. There was the hoopla, the lucky dip, the white-elephant stall where you could buy your neighbour’s unwanted ornaments and then win them back again in the raffle.

And then, of course, there was the coconut shy — a row of battered coconuts perched on wooden stands, daring us to knock them down. We hurled wooden balls with all our might, only to see the coconuts wobble but refuse to budge. Rumour had it the stallholders nailed them in place, and we half believed it.

The Competitions

Inside the marquee, the serious business of judging took place. There were categories for best sponge cake, finest jam, longest marrow, and, of course, the inevitable cucumbers. Mr. Pickering was always convinced of victory, proudly displaying his latest specimen, which seemed to grow longer with every telling. When he lost, he muttered darkly about bias and conspiracies, while Mrs. Clarke from next door celebrated yet another “Highly Commended” for her Victoria sponge.

Children entered the fancy-dress parade, shuffling self-consciously across the stage in costumes stitched together by ambitious mothers. One year, I went as a pirate, complete with an eye patch made from black felt and a cardboard cutlass. I didn’t win, but I felt magnificent all the same.

Games and Mishaps

The sack race was always a highlight — and a hazard. We bounced and stumbled across the grass, legs tangled, the finish line swaying in the distance. Once, two of us collided mid-hop, and the sight of us rolling helplessly on the ground sent the crowd into peals of laughter.

The tug-of-war was the grand finale. Teams of villagers hauled on a thick rope, faces red, shoes digging into the grass. One year the rope snapped with a crack like a gunshot, sending both sides sprawling in a heap. Nobody was hurt, but the laughter could be heard halfway to Walton.

The Raffle

No fete was complete without the raffle. Tickets were sold weeks in advance, pink and yellow stubs clutched in hopeful hands. The prizes were proudly displayed: a fruit basket, a bottle of sherry, a tin of biscuits, and, most coveted of all, the giant teddy bear that sat regally on the table.

When the vicar drew the winning numbers, the entire crowd held its breath. Cheers erupted, groans followed, and the teddy bear went home with a child whose mother muttered that she had “no room for such nonsense.”

The Magic of the Day

By the end of the afternoon, the grass was littered with torn raffle tickets and sweet wrappers, the band was hoarse, and the children were sticky with toffee apples and triumph. The sun dipped low, casting a golden glow over the Green, and tired families drifted home, clutching their winnings and their memories.

To a child, the fete was magic itself: a day when the ordinary rules of life were suspended, when you could win treasure with a sixpence, when the village seemed transformed into a fairground. Even now, the smell of coconut matting or the faint sound of a brass band can carry me back to those glorious afternoons on the Green, when Sunbury came together in laughter, rivalry, and joy.

Chapter Eight: Rainy Days

For all the golden afternoons and endless games by the river, childhood in Sunbury-on-Thames in the 1960s was not without its share of grey, drizzly days. When the clouds pressed low over the rooftops and the rain pattered steadily against the windows, our adventures were curtailed, and the world shrank to the size of a sitting room.

The Scent of Rain

Rain had its own smell — a mix of damp pavements, wet earth, and washing hastily dragged off the line. You could hear it too: the soft hiss on leaves, the drip-drip from gutters, the occasional gurgle as the drains struggled under the weight of it all. From inside, it made the world feel smaller, more secret.

Coats hung by the door, damp and heavy, steaming faintly in the warmth of the hallway. Shoes clustered on newspaper, leaving dark puddles on the lino. Mothers sighed at the extra washing, while children sulked at the loss of football and marbles.

Games Indoors

But soon the sulking gave way to invention. Rainy days meant board games: Ludo, Snakes and Ladders, Monopoly if we had the patience. The dice clattered on the table, and tempers rose when someone landed on “Mayfair with a hotel.” More often than not, games ended with a quarrel, a sulk, or the board being tipped onto the carpet in protest.

Card games were another standby. We played endless rounds of Snap or Happy Families, slapping cards down with more energy than skill. “Mr. Bun the Baker!” we’d shout, triumphant. Inevitably, the pack ended up bent, dog-eared, and scattered under the sofa.

When games grew dull, we turned to building forts out of chairs and blankets, creating dark dens where we whispered secrets and told ghost stories while the rain tapped on the windows. A torch under the chin transformed us into monsters, much to the horror — and delight — of younger siblings.

Comforts of the Kitchen

The kitchen became the heart of rainy days. The kettle sang constantly, filling the house with steam. Mothers baked — not fancy cakes, but solid, comforting fare: scones, rock buns, bread pudding. The smell of something rising in the oven mingled with the sharp tang of wet coats and the faint mustiness of the carpet.

We hovered hopefully, waiting for the moment when a tray of scones was pulled out, still hot, to be split open and spread with butter that melted into golden pools. Nothing ever tasted quite so good as food eaten while the rain hammered at the windows.

Television Treats

By the mid-60s, more homes had televisions, and rainy afternoons meant huddling in front of the flickering black-and-white screen. Programmes were sparse, but we didn’t care. Children’s television, Blue Peter or Crackerjack, was greeted like manna from heaven. We sat cross-legged on the rug, eyes wide, the outside world forgotten.

Sometimes, though, the signal failed, and the screen dissolved into snow. A quick fiddle with the aerial — a bent coat-hanger, in our case — usually restored order, though not without someone getting a mild shock.

Evening Drowsiness

By evening, the house had taken on a snug, cocoon-like feeling. Curtains drawn tight, lamps glowing, the rain a steady percussion outside. Fathers came home damp from the station, shaking out umbrellas and muttering about “typical English summers.”

After tea, the wireless might be switched on, filling the room with the soothing voices of the Light Programme. We dozed in chairs, cats curled on laps, the warmth of the fire chasing away the damp. The world outside no longer mattered.

The Gift of Rain

As children, we resented rainy days — they stole our freedom, kept us indoors, denied us the thrill of the river and the Green. But in memory, those grey afternoons seem precious. They taught us resourcefulness, imagination, and the comfort of being safe indoors while the weather raged outside.

Even now, when I hear the soft hiss of rain on a windowpane, I am back in that Sunbury sitting room: the smell of scones in the oven, the clatter of dice on the table, the laughter of siblings in a blanket fort, and the deep, abiding comfort of a home made warm against the storm.

Chapter Nine: Mischief and Escapades

For all the order of Sundays and the quiet of rainy days, there was another side to childhood in Sunbury — the side that involved muddy knees, bruised elbows, and a great deal of scolding afterwards. Mischief was as much a part of growing up as homework, and it was always more fun.

Trees and Dens

Sunbury Park was our kingdom. The Mansion stood there in all its faded grandeur, a place we were half afraid of and half drawn to, but the trees were what called us. We climbed them like squirrels, scrambling up the trunks and swinging from branches, shouting to one another like explorers in the jungle.

Dens sprouted everywhere — behind hedges, in overgrown corners, even in old coal bunkers. They were our castles, our headquarters, our secret bases. We decorated them with scavenged treasures: a broken chair, an empty golden syrup tin, a couple of jam jars. Membership to a den came with elaborate rituals: passwords whispered under breath, solemn oaths sworn on conker shells.

Of course, secrecy was impossible in a village where everyone knew everyone. Mothers soon discovered where we were hiding, but they pretended not to, content so long as we came home in one piece.

Forbidden Grounds

The Mansion itself was irresistible. Its cracked steps and dark windows promised ghosts, and though we swore to each other that we didn’t believe in such things, none of us lingered too long by the iron gates once dusk fell.

One summer afternoon, we dared each other to sneak inside the grounds. Heart hammering, I crept across the lawn, convinced that at any moment a ghostly figure would appear at the window. Suddenly a curtain twitched — or at least I thought it did. That was enough. We bolted back to the gate, shrieking with laughter, our bravery forgotten.

For weeks afterwards we told and retold the story, each time embellishing the details: the pale hand at the glass, the whisper on the wind, the shadow on the staircase. We terrified ourselves and loved every moment of it.

Go-Karts and Crashes

When we weren’t haunting the Mansion, we were building go-karts. These were not sleek, shop-bought machines but contraptions cobbled together from pram wheels, bits of wood, and more string than was sensible.

We raced them down the hill near the Green, steering with bits of rope and trusting to luck. Inevitably, they rattled apart halfway down, spilling us into the grass. Knees were grazed, trousers torn, and mothers exasperated. Yet by the next week, we were hammering the pieces back together, convinced that this time our kart would rival a racing car.

One memorable attempt ended with Billy Hawkins crashing into Mrs. Clarke’s front gate, splintering a paling and scattering marigolds. Mrs. Clarke stormed out, red-faced and roaring, while Billy grinned sheepishly from the wreckage. We helped him rebuild, of course, though the gate was never quite the same again.

Small Rebellions

Mischief didn’t always involve danger. Sometimes it was smaller rebellions: scrumping apples from an overhanging tree, sneaking a cigarette filched from an older brother, or knocking on doors and running away. These acts felt daring, though they were rarely more than harmless pranks.

The local policeman, a kindly figure on a bicycle, seemed to appear out of nowhere whenever we were up to no good. “Now then, boys,” he’d say, “what are you up to?” His raised eyebrow was usually enough to scatter us in all directions. Yet he never told our parents, and we secretly adored him for it.

Scrapes and Scoldings

Of course, mischief had its price. We came home with torn clothes, muddy shoes, and stories that didn’t always match the evidence. Mothers tutted, fathers shook their heads, and we promised to be more careful next time. The promises never lasted.

Because the truth was, those scrapes and escapades were the best part of childhood. They gave us stories to tell, scars to compare, and laughter that echoed long after the bruises had faded.

Mischief Remembered

Looking back, I realise that our adventures were small by any grand measure — no battles won, no treasures found. Yet to us, they were everything. Each tree climbed, each ghost imagined, each go-kart crash felt like a brush with glory.

And in the memory of Sunbury, it is those moments of mischief — the daring, the laughter, the sense of living just a little on the edge — that shine brightest of all.

Chapter Ten: The Long Summer Evenings

If childhood had a colour, for me it would always be the gold of a summer evening in Sunbury-on-Thames. After days spent roaming the riverbanks, scrambling over trees, or tearing down hills in wobbly go-karts, evenings arrived like a gift — soft, warm, unhurried. They were the part of the day when everything seemed possible, and yet nothing was expected of us.

The Glow of Dusk

The sun lingered long on those evenings, sinking slowly behind the rooftops and painting the Thames in ripples of orange and pink. The air grew cooler, filled with the scent of cut grass, pipe smoke, and the faint tang of someone’s barbecue or bonfire. Midges danced in the light, and swifts swooped above, their cries sharp against the hush of the fading day.

We gathered on the low wall outside our houses, legs swinging, comparing the day’s bruises and swapping plans for tomorrow. Sometimes we sat in silence, chewing liquorice or blowing bubbles from penny tubs of soapy water, simply content to exist in the golden glow.

The Street as a Stage

The street belonged to us then. Cars were few, and the occasional Morris Minor or Ford Anglia that trundled by did so slowly enough for us to scatter and return moments later. We played kick-the-can, hide-and-seek, or “What’s the time, Mr. Wolf?” until the shadows grew long.

From open windows came the sounds of families finishing supper: the clink of plates, the murmur of wireless programmes, the laughter of siblings squabbling over chores. Curtains twitched, neighbours exchanged nods, and the whole village seemed bathed in a sense of quiet safety.

Mothers Calling Us In

One by one, voices rang out across the street. “John! Tea’s ready!” “Susan! Bedtime!” We tried to ignore them, pretending not to hear, but sooner or later the summons grew firmer. Reluctantly, we said our goodbyes, promising to meet again in the morning for another round of adventures.

There was always a pang as I left the gang behind, walking up the garden path to the sound of laughter still echoing in the dusk. Yet the warmth of home awaited: slippers by the door, the smell of supper, the comfort of knowing the day was safely tucked away.

The Sounds of Evening

Inside, fathers sat with newspapers spread like sails, pipes puffing, while mothers ironed shirts for the week ahead. The wireless played softly in the background — Sing Something Simple, or perhaps the Top 20 countdown if we were lucky. Sometimes a train rumbled distantly across the fields, its whistle carrying through the open window like a lullaby.

For us children, the day ended in bed with a book under the blankets, torch in hand until the batteries died. Outside, the last glow faded, and the world slipped into darkness.

The Magic of Ending

Those evenings were never dramatic. They held no grand adventures, no feats of daring. And yet they shimmer in my memory with a kind of quiet perfection. It was the time when the world felt both vast and close, when friendship was measured in promises shouted across the street, and when the setting sun seemed to bless everything it touched.

Even now, when twilight falls, I am carried back to Sunbury in the 1960s: the swifts crying overhead, the smell of cut grass in the air, mothers calling us in, and the golden light of childhood settling softly over the village.