The Clockmaker of Clonmore Castle

The Clockmaker of Clonmore Castle

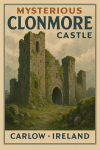

They say that time stands still at Clonmore Castle.

Not just because it’s a ruin — all ivy-clad and half-swallowed by the earth — but because on certain misty evenings, if you linger too long among its crumbling walls, time really does stop. Or skips. Or doubles back. Or worse.

I didn’t believe any of that, of course, not until the day I met the Clockmaker.

It began with a school trip, the kind nobody expects to remember. Rain. Ruins. A teacher droning on about the Normans and defensive towers while we snuck crisps and moaned about the cold.

Then I saw it. Behind the eastern tower, where a wall had mostly collapsed, there was a passageway I’d never noticed before — narrow and dark, overgrown but clearly deliberate. Something pulled me toward it, like the scent of a memory you’re sure doesn’t belong to you.

The others wandered off. I went in.

The tunnel was damp, lit faintly by slits in the stones. And at the end — a chamber. Round. Hidden. A place not marked on any map or brochure. At its centre stood a curious device: a tall, gleaming clock made of brass and bone, gears turning in ways that defied logic. It ticked not once a second but once every third thought, or so it felt.

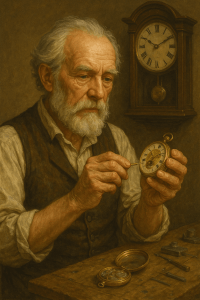

That’s when he stepped forward — thin as smoke and dressed in tails of dusty velvet. His eyes clicked like dials as he blinked. He smiled without teeth.

“You found me,” he said.

“I wasn’t looking,” I replied.

“No one ever is,” said the Clockmaker of Clonmore.

He told me he’d lived here long before the castle fell to ruin. Before Cromwell came. Before the Normans. He didn’t build the clock — it built him. Long ago, he had been a simple watchsmith in a nearby village, obsessed with precision. But time, he found, was not precise. It leaked. It fractured. And one day, in the hills above Clonmore, he found the remains of a strange device — part machine, part organism — buried under an ancient yew tree.

He brought it here. Fed it cogs and prayers. Now, he could walk between moments like stepping stones. He existed in a permanent yesterday-tomorrow. He hadn’t aged in centuries.

“But I grow… weary,” he admitted, fiddling with a minute hand that hummed like a bee. “Time is heavy, when you carry too much of it.”

I asked why he was telling me all this.

“Because clocks need winding,” he said. “And every few hundred years, a curious child wanders in.”

He reached out. His fingers brushed my wrist. Everything stopped.

The rain outside froze mid-fall. Birds hung in the sky like paper cut-outs. I couldn’t blink. Couldn’t breathe. The clock let out a sound — throomp — like a heartbeat made of thunder. Then, just as suddenly, it all snapped back.

I was alone.

The chamber was empty. No clock. No man. Just dust and roots and the distant sound of my classmates calling my name.

But on my wrist, where he had touched me, was a mark: a tiny brass gear, embedded beneath the skin, ticking ever so faintly.

I haven’t told anyone. Not really. Not until now.

But every so often, when I’m late for school or wish a moment would last forever, I twist my wrist just so… and the world skips, or stutters, or rewinds.

And I think of him.

The Clockmaker of Clonmore.

Still ticking.

Still waiting.