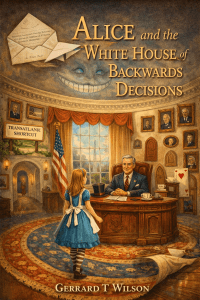

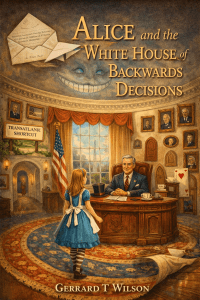

Chapter One

You are cordially invited to attend a matter of considerable confusion.

Washington, Immediately.

“Morning, Alice.”

“We have been expecting you before you arrived.”

“This is Washington.”

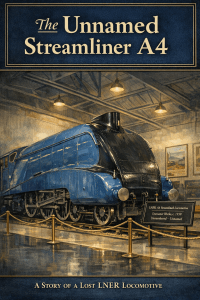

Chapter One

No one at Doncaster Works could later remember exactly when the locomotive was finished.

The paperwork suggested March 1939, though the works foreman always insisted it had been earlier. The painters said they remembered applying the final coat of garter blue on a cold morning when the varnish refused to dry properly. The fitters remembered the valve gear going together more smoothly than expected. The apprentices remembered nothing at all — which, in its way, proved the locomotive had never entered ordinary service.

What everyone agreed upon was this:

The engine had been completed.

And then, for reasons no one ever properly recorded, it had simply stayed where it was.

Without a number.

Without a name.

Without a duty.

Full story coming here soon.

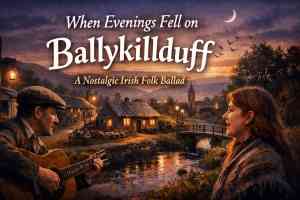

The fire crackled merrily in the hearth of the Ballykillduff cottage, casting dancing shadows on the low-beamed ceiling. Outside, a full moon bathed the frosty fields in a soft, silvery glow, the silent world blanketed in fresh snow. But inside, it was warmth and comfort, a cocoon against the winter’s bite.

Seamus, his spectacles perched on the end of his nose, carefully mended a fishing net, his movements slow but precise, honed by years of patient work. Across the small wooden table, Maeve’s needles clicked a gentle rhythm, weaving strands of wool into a new blanket, her hands as nimble as they had been sixty years ago, though now a little gnarled by time. Between them, a steaming teapot promised another cup, and the scent of freshly baked soda bread filled the air.

Their old dog, Finn, lay curled by the fireside, dreaming canine dreams, his occasional whimper a soft counterpoint to the quiet hum of the room. On the mantelpiece, faded photographs smiled down—their children as babes, their wedding day, a generation of memories captured in sepia tones. Above the mantel, a painting of a summer harvest, vibrant and golden, was a window to another time, a vivid echo of the image we just created.

“Remember that harvest, Maeve?” Seamus murmured, his voice soft, not breaking the peace but enriching it. “The year young Michael nearly tipped O’Malley’s wagon, trying to show off.”

Maeve chuckled, a warm sound that crinkled the corners of her eyes. “And your father nearly had a fit! You were always one for teasing, Seamus Finnegan.”

He smiled, a gentle warmth spreading through him that had nothing to do with the fire. “We worked hard, didn’t we? But there was always laughter, always a song.”

Maeve nodded, her gaze drifting to the moonlit window. “And those nights, after the fields were cleared, the whole village would gather. Music, dancing… you’d try to get me to dance, always with two left feet.”

“I did my best!” Seamus protested playfully, a twinkle in his eye.

The conversation faded again into comfortable silence, punctuated by the fire’s gentle roar and the rhythmic click of Maeve’s needles. They didn’t need many words; decades of shared life, of triumphs and sorrows, of sun-drenched harvests and snow-kissed evenings, had woven a tapestry of understanding between them. Each glance, each shared sigh, spoke volumes. This cozy winter evening wasn’t just a moment in time; it was a distillation of all the moments before, a quiet, contented testament to a lifetime of love lived simply, deeply, in the heart of Ballykillduff. The past wasn’t gone; it was right here, in the warmth of the fire, the scent of the bread, and the steadfast love that glowed between them, bright as the winter moon.

The sun beat down on Ballykillduff, a golden hammer forging memories into the very earth. It was the height of summer harvest, and the fields shimmered with ripe wheat, a sea of gold stretching to the gentle hills beyond. Old Man Finnegan, his back a permanent curve from decades of toil, leaned on his scythe, wiping a brow beaded with sweat. “Aye,” he’d often say, “these are the days to remember.”

He watched the rhythm of the village unfold before him. Young Michael, barely a man, grunted as he wrestled a heavy sheaf onto a growing stack, his freckled face red with effort and a burgeoning pride. His mother, Mary, moved with the quiet grace of a seasoned farmer, her hands calloused but nimble, gathering stalks into neat bundles. Even little Brigid, no older than five, chased after her dog, a scruffy terrier named Rusty, as it darted through the stubble, imagining herself a grand huntress.

In the distance, the chugging of Mr. O’Malley’s tractor, a relatively newfangled contraption, mingled with the shouts and laughter of the men loading the hay wagon. It was a faster way, to be sure, but Finnegan preferred the quiet swish of the scythe, the feel of the earth beneath his worn boots. He remembered his own youth, when every grain was cut by hand, every stack built with sweat and song.

The stone church steeple pierced the azure sky, a silent sentinel watching over generations of harvests. White-washed cottages nestled among the trees, their chimneys hinting at the warm meals and tired bodies that would soon fill them. The air was thick with the scent of cut grass, warm earth, and the promise of a bountiful supper.

As the sun began its slow descent, painting the clouds in hues of orange and pink, Finnegan smiled. These weren’t just fields of wheat; they were fields of shared labor, of community, of life itself. He thought of his own father and grandfather, their spirits woven into the very fabric of Ballykillduff. “Aye,” he murmured again, a soft sigh escaping his lips, “these are the days that last.” The memories, golden and vivid, were as real as the setting sun, cherished treasures of a time when the land and its people moved as one, under the generous hand of a summer sky.

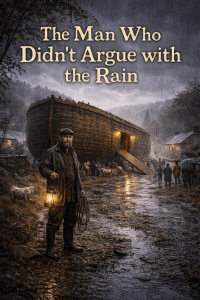

By the fourth week of rain, Ballykillduff stopped pretending it was temporary.

The first week had been called unfortunate. The second was concerning. By the third, people were beginning to mutter phrases like biblical and I don’t remember it ever being this wet, which in Ballykillduff was the traditional signal that something had gone deeply wrong with reality.

Jimmy McGrogan noticed it on a Tuesday.

Not the rain itself—everyone noticed that—but the way it behaved. Rain usually arrived with a bit of manners. It fell, it soaked, it left. This rain had moved in. It lingered. It leaned against doorframes. It watched through windows. It fell at angles rain had no right to fall at, drifting sideways, upwards occasionally, as though unsure which way gravity was supposed to be working that week.

Jimmy stood in his yard, rain dripping off the brim of his cap, watching the river swell until it looked less like a river and more like a decision someone had made in a panic.

“That’s not stopping,” he said aloud.

This was important, because Jimmy McGrogan was not a man given to exaggeration. When Jimmy said something wasn’t stopping, it usually meant it had already passed reasonable and was heading briskly toward legend.

By Wednesday morning, the chickens were refusing to come out of the shed, the dog was sulking under the stairs, and the postman had taken to delivering letters by throwing them vaguely in the direction of houses and hoping for the best.

That was when Jimmy began measuring.

No one noticed at first. Ballykillduff had learned long ago that noticing Jimmy McGrogan too early only made things worse. He paced the length of his field with a tape measure and a look of grim concentration. He made notes on the backs of old envelopes. He stared at the sky, nodded once, and went inside to make tea so strong it could have removed paint.

On Thursday, he bought timber.

“Doing repairs?” asked Mrs. Donnelly in the hardware shop.

“Something like that,” said Jimmy.

On Friday, the shape became unmistakable.

It was an arc. Not a curve, not a suggestion—an unmistakable, deliberate arc, rising from the soaked earth behind Jimmy’s house like an idea that had finally committed to itself. By Saturday afternoon, half the village was standing at the hedge, umbrellas sagging, watching him work.

“Is that…?” someone began.

“Yes,” said Jimmy, without looking up.

“But—”

“Yes.”

“Are you sure?”

Jimmy drove a nail home with unnecessary emphasis.

By Sunday, the rain intensified, as though offended.

The river spilled over its banks. The lower lane disappeared entirely, leaving only the tops of familiar signposts sticking out like accusations. A cow appeared in O’Flaherty’s yard, confused but polite. The church steps developed a small waterfall, which Father Keane insisted on blessing, just in case.

And Jimmy McGrogan kept building.

By the time the arc was finished, it was enormous—solid timber ribs, sealed seams, a roof sloping just enough to argue with the rain instead of surrendering to it. A door wide enough for decisions. A ramp thoughtfully added, “for anything with opinions,” Jimmy explained.

“What exactly do you think is going to happen?” asked Mrs. Donnelly.

Jimmy wiped his hands on his trousers and looked out across Ballykillduff, now shimmering with water and reflection.

“I don’t think,” he said. “I’ve checked.”

That night, the rain reached a pitch it had been working toward all along.

It fell with purpose. With memory.

People woke to water at their doorsteps, then in their kitchens, then tapping politely at the stairs. And when they went outside—boots sloshing, torches bobbing—they found Jimmy already there, opening the great wooden door of the arc.

He did not shout. He did not panic.

He simply nodded and stepped aside.

By morning, Ballykillduff floated.

Not dramatically—no roaring waves, no lightning—but gently, stubbornly, as though it had decided to refuse sinking out of spite. The arc rocked slightly, tethered to what remained of the higher ground, filled with people, animals, boxes of things someone couldn’t quite bear to leave behind.

And then, just as suddenly as it had begun, the rain stopped.

It did not slow. It did not apologise.

It stopped.

Water drained away with reluctant sighs. The river returned to something like itself. Mud claimed the streets. Ballykillduff reappeared, damp, bewildered, but intact.

Jimmy McGrogan dismantled the arc the following week.

Used the timber for sheds, fences, and one very fine bus stop. He never spoke much about it afterward, except once, when someone asked him how he’d known.

Jimmy thought for a moment.

“Well,” he said, “when the rain forgets to leave, it’s best to be polite—but prepared.”

And in Ballykillduff, no one ever argued with that.