Chapter One

You are cordially invited to attend a matter of considerable confusion.

Washington, Immediately.

“Morning, Alice.”

“We have been expecting you before you arrived.”

“This is Washington.”

Chapter One

One followed a rabbit down into the dark,

The other a cyclone that left its own mark.

On a road paved in gold, where the green towers rise,

They met for a moment and shared their surprise.

Both wearing ribbons and dresses of blue,

In worlds where the logic is never quite true.

One spoke of riddles and tea with a cat,

The other of wizards and where home was at.

“The cards are all shouting!” the blonde one declared,

While the girl with the braids found herself rather scared.

“There’s a lion who cries and a man made of tin,

And a city of emeralds we’re meant to go in.”

They paused by the signpost that points the same way,

In the soft, hazy light of a magical day.

With a sip of her tea and a click of red heels,

They pondered how living a fairy tale feels.

No logic or compass could show them the door,

Between Kansas, and London, and Never-Before.

But for one quiet second, the wanderers stood—

Two girls lost in dreams, as all wanderers should.

Alice Meets Dorothy

The sun, a pale, milky orb in the sky, cast long, shifting shadows along the path of gold bricks. Dorothy, her blue gingham dress a familiar comfort, stood with a curious expression. Before her, a girl with hair the color of sunlight and a similar blue dress held a steaming teacup, a delicate saucer resting precariously on the rough, uneven bricks.

“Emerald City?” the blonde girl mused, peering at the signpost that read the same words twice. “How perfectly uninteresting. All cities are rather green, if you ask me, with all the grass and trees.”

Dorothy blinked. “But it’s Emerald City! Everything is green inside. The people wear green spectacles, and the palace is green, and—”

“Oh, like a rather large, sparkly bottle then?” the other girl interrupted, taking a sip of her tea. “I once met a bottle that contained a rather rude pigeon. Do you have many rude pigeons here?”

“Pigeons?” Dorothy frowned, trying to recall. “Well, I haven’t really noticed. I’ve been so busy trying to get to the Wizard.”

“A wizard, you say?” The blonde girl’s eyes widened slightly. “How dreadfully dull. Are they anything like a Dodo? Or a March Hare, perhaps? They are quite good at making things disappear, though often they just hide them.” She gestured with her teacup towards the path. “Are you going to a tea party?”

Dorothy shook her head, a little bewildered. “No, I’m going to ask the Wizard to send me home to Kansas. And my dog, Toto, needs to go home too.” She looked around. “Where’s your dog?”

“A dog? Oh, I don’t have a dog,” the girl replied, looking down at her cup. “I have a rather persistent White Rabbit. He’s always late for something or other. And a Ches—” She stopped, a peculiar glint in her eye. “No, I mustn’t mention him. It makes his smile appear, and then he’s terribly difficult to remove from conversations.”

Dorothy tilted her head. “A rabbit that’s always late? And a disappearing smile?” This world felt even stranger than Oz. “Are you… lost too?”

The blonde girl finally looked directly at Dorothy, a flicker of something familiar in her gaze. “Lost? One is never truly lost when one has a destination, however illogical. Though I confess, ‘Emerald City’ wasn’t on my itinerary. I was rather hoping for a game of croquet.” She gestured to the fallen teacup beside her feet. “Though this tea has gone quite cold, I daresay. Would you care for a cup?”

Dorothy looked from the cold teacup on the ground to the girl’s outstretched hand, holding another. The Emerald City gleamed in the distance. “I suppose… a small cup couldn’t hurt.” She had, after all, met a talking lion and a scarecrow. What was one more peculiar encounter on the road?

The meeting of the girls was polite, but the meeting of their companions would be a much more baffling affair!

Toto was a dog of simple, sturdy principles. He liked bones, he liked chasing the occasional crow, and he liked things to stay where he could see them.

He was sniffing a patch of particularly bright poppies when a tail appeared. Just a tail. It was striped, purple, and twitching lazily in the air about four feet off the ground. Toto gave a sharp, inquisitive bark.

“Oh, do stop that,” a voice purred from the empty air. “It’s dreadfully loud, and I’m trying to contemplate the nature of a ‘Kansas’.”

A pair of wide, yellow eyes flickered into existence above the tail, followed by a grin so wide it seemed to be holding the rest of the face together. Toto’s ears flattened. He was used to monkeys with wings and lions who cried, but a cat that was only half-finished was an insult to his canine senses.

Toto growled, a low vibration in his chest.

“A growl?” the Cheshire Cat remarked, its ears finally materializing. “How singular. In my forest, we growl when we’re pleased and wag our tails when we’re angry. Or is it the other way around? It hardly matters, since I haven’t got a tail at the moment.”

The Cat vanished entirely, leaving only the floating grin. Toto lunged, snapping at the empty air where the nose should have been, but his teeth met only the scent of tea and ozone.

“You’re quite a determined little thing,” the grin said, reappearing behind Toto’s left ear. “But you’ll find that biting the air is a very hungry business. Tell me, does your girl always walk on such a yellow road? It’s a bit loud for the eyes, don’t you think?”

Toto turned in a circle, barking at the floating teeth. He didn’t care about the color of the road; he just wanted this cat to pick a shape and stick to it.

“He’s not a dog, Toto,” Dorothy called out from a distance, sensing the commotion.

“And he’s certainly not a rabbit,” Alice added, peering over.

The Cheshire Cat began to fade again, starting with the tip of its tail. “We’re all mad here, little dog. Some of us just have the decency to hide the evidence.”

With one final, mocking wink of a yellow eye, the cat was gone. Toto sniffed the spot, let out one final, huffy “woof,” and trotted back to Dorothy’s side. He decided then and there that he much preferred the Wicked Witch; at least she stayed solid when you bit her.

Everyone in Ballykillduff knew the rhyme. They learned it young, usually from someone older who lowered their voice for the last line.

One for sorrow.

Two for joy.

Three for a girl.

Four for a boy.

Five for silver.

Six for gold.

Seven for a secret, never to be told.

Most people laughed at it. Some people touched wood. Nobody ever talked about seven.

Alice saw them on a Tuesday morning, standing along the hedge at Curran’s Lane.

Seven magpies. Neat as fence posts. Silent as if silence were a rule they were following carefully.

Alice stopped walking.

The hedge itself felt wrong. Not dangerous. Just… held together too tightly, like someone smiling for longer than was comfortable.

She counted them twice. She always did when things felt important.

One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven.

All seven turned their heads together and looked at her.

“Right,” Alice said quietly. “It’s that sort of day.”

People passed along the lane without noticing anything at all. Mr Keane walked by whistling. Mrs Donnelly hurried past with her shopping. No one looked at the hedge. No one slowed down.

Only Alice stood there.

The magpies did not speak. They had never needed to.

Long ago, Ballykillduff had made a decision.

It was not a cruel decision. It was a tired one.

Something sad had happened. Something that could not be fixed. A thing with a name, and a place, and a day that people still remembered too clearly. After a while, the village agreed to stop saying it out loud. Not because it wasn’t real, but because remembering it every day was making it impossible to live the next ones.

So the remembering was set aside.

And the magpies stayed.

They stayed because someone had to remember, and magpies are very good at keeping what others lay down. Not just shiny things, but moments, and names, and truths that no longer fit anywhere else.

The rhyme was never meant to predict luck.

It was a warning.

Seven magpies meant a place was carrying a memory it no longer wanted to hold.

One of the magpies hopped down from the hedge and pecked at the ground. Not at soil, but at a flat stone half-buried near the roots. A stone no one stepped on, though no one could have said why.

Alice knew what was being asked of her.

She did not need to know the whole story. She did not need names or details. She only needed to do one thing the village had not done in a very long time.

She knelt and placed her hand on the stone.

“I know,” she said, softly.

That was all.

Not what she knew. Just that she knew something had been there. Something had mattered.

The hedge loosened. Just a little. The air moved again.

When Alice stood up, there were only six magpies left.

They were already arguing with one another, hopping and chattering, busy once more with ordinary magpie business. Shiny things. Important nonsense. The everyday work of being alive.

The seventh magpie rose into the air and flew away, light now, its work finished at last.

Alice walked on down the lane.

Behind her, Ballykillduff continued exactly as it always had. But somewhere deep in its bones, a small, quiet weight had finally been set down properly instead of being hidden away.

And the rhyme, for once, was at rest.

Everyone in Ballykillduff knew the rhyme. They said it quickly, like a spell that worked better if you didn’t linger on it.

One for sorrow.

Two for joy.

Three for a girl.

Four for a boy.

Five for silver.

Six for gold.

Seven for a secret, never to be told.

Alice had already seen seven magpies once before, and she knew what that meant.

So when she walked along Curran’s Lane and saw eight, she stopped dead.

Seven stood along the hedge, silent and still.

The eighth stood on the path itself, blocking the way.

“Well,” Alice said, “that’s new.”

The eighth magpie was smaller than the others and less patient. It tapped one foot, then the other, as if waiting for a late train.

Seven magpies meant the village had forgotten something important. A sad thing. A thing everyone had agreed not to talk about.

That part had already been done.

Ballykillduff had remembered.

But the eighth magpie had arrived because remembering had changed nothing yet.

The bird pecked sharply at the ground.

Alice followed its beak and saw the problem at once.

The old path had collapsed further down the lane. A fence lay broken. The shortcut people once used had never been repaired. Long ago, someone had been hurt there. That was the secret. That was why people stopped using it.

They had remembered the accident.

They had never fixed the path.

“Oh,” said Alice. “You mean that.”

The eighth magpie nodded briskly.

It wasn’t here for memory.

It was here for mending.

Alice went back to the village and told people what she’d seen. Not the whole story. Just enough.

By evening, someone had brought tools. Someone else brought boards. Someone else brought tea.

By the next morning, the path was safe again.

When Alice returned to Curran’s Lane, there were only seven magpies on the hedge.

Then six.

Then none at all.

The eighth magpie was gone first.

It always is.

Because once something is put right, there is no need for it to stay.

And the rhyme, at last, had room for one more line, though nobody ever said it aloud:

Eight for the thing you do about it.

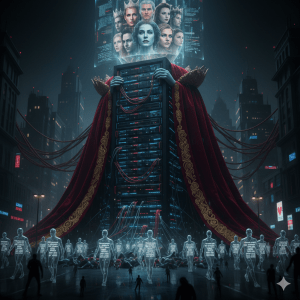

The story you are about to read is not a fantasy. It is an autopsy.

When Lewis Carroll wrote Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865, he was satirizing the rigid, nonsensical logic of Victorian education and law. He used a rabbit hole to show how a child’s innocence is swallowed by the arbitrary rules of adulthood.

In our modern era, we do not fall through holes in the earth. We descend through pixels.

“The Terms of Service” is an allegory for the year we are currently living in—a time when the “elites” are no longer just people in high offices, but the very algorithms they have unleashed. We find ourselves in a world where “Truth” has been replaced by “Engagement,” where “Citizens” have been downgraded to “Users,” and where our most private thoughts are harvested like raw ore to power a machine that never sleeps.

This story is intended to hold no punches. It explores the uncomfortable reality that our modern “Wonderland” is not a prison forced upon us by a cabal of geniuses. Instead, it is a gilded cage we have built for ourselves, one convenient click at a time. The institutions we fear—the media, the tech giants, the financial structures—are merely mirrors reflecting our own collective desire for distraction over depth and safety over sovereignty.

As you follow Alicia through the Institutional Layers of New Ouroboros, I invite you to look closely at the “Slang” in the Appendix and the “Friction” in the Tea Party. Ask yourself:

When was the last time I looked away from the screen long enough to see the sky in its own color, rather than the shade I was told to expect?

The Queen is waiting. The Rabbit is glitching. And the Terms of Service are non-negotiable.

Proceed at your own risk. Click HERE to read the full story

Alice had returned to Wonderland for one reason: nostalgia. Big mistake.

The place had gone full corporate dystopia. The White Rabbit was now a crypto bro shilling “CarrotCoin,” the Mad Hatter ran an NFT tea party where every cup was a unique digital collectible worth exactly nothing, and the Queen of Hearts had rebranded as an influencer with the handle @OffWithTheirHeads69.

Worst of all, the Cheshire Cat had launched “GrinR,” Wonderland’s premier ride-sharing app. Slogan: “We vanish when you need us most.”

Alice tapped the app. Destination: Home.

Vehicle arriving: “Kevin the Boar – 4.9 stars (deducted 0.1 for chronic truffle addiction).”

Kevin arrived looking like a warthog that had lost a bet with a taxidermist. He wore a tiny saddle, a Bluetooth earpiece, and an expression that screamed, “I went to boar school for this?”

Alice climbed on. Kevin immediately side-eyed a glowing mushroom.

“Don’t even think about it,” Alice warned.

Kevin thought about it. Hard.

The ride began politely, past teacup gardens, under rainbow toadstools, until Kevin spotted the Holy Grail of truffles: a massive, glistening beauty sprouting right in the middle of the Queen’s private croquet lawn.

Kevin floored it.

“KEVIN, NO!” Alice screamed, clutching his mane as they bulldozed through a hedge maze like it was made of tissue paper.

Card soldiers dove left and right. One guard yelled, “License and registration!” only to be flattened into the shape of the two of clubs.

They skidded onto the croquet field just as the Queen was about to execute a flamingo for “unsportsmanlike squawking.”

Kevin launched himself at the truffle like a furry missile, uprooted it, and inhaled it in one obscene slurp. Then he let out a belch so powerful it parted the Queen’s wig, revealing a tattoo that read “Live, Laugh, Lob.”

The entire court froze.

The Queen’s face turned the color of a ripe tomato having a stroke.

“OFF WITH HIS TROTTERS!” she shrieked.

Alice, panicking, did the only thing she could think of: she pulled out her phone and fake-reviewed on the spot.

“Your Majesty, please! Kevin has 4.9 stars! He’s verified! He accepts tips in acorns!”

The Queen paused, mallet raised. “Reviews?”

Alice nodded frantically. “Read them yourself! ‘Best ride ever, 10/10 would be stampeded again.’ ‘Kevin took a shortcut through a caterpillar’s hookah lounge, legendary.’ ‘Only complaint: he ate my picnic.’”

Kevin, sensing an opportunity, turned on the charm. He sat. He gave paw. He even attempted a smile, which looked like a constipated bulldog discovering taxes.

The Queen lowered her mallet. “Fine. But he’s banned from my lawn. And someone get this pig a breath mint.”

As they trotted away, the Cheshire Cat materialized on Kevin’s head like a smug helmet.

“Not bad for a rookie driver,” he purred. “Next fare’s the Dormouse, he tips in half-eaten crumpets.”

Alice groaned. “Just get me out of here.”

Kevin suddenly braked. In the path ahead: a single, perfect truffle.

Alice glared. “Kevin. I swear to Lewis Carroll.”

Kevin looked back at her with big, innocent eyes.

Then he winked.

And floored it again.

Somewhere in the distance, the Queen’s scream echoed: “OFF WITH ALL OF THEM!”

Alice clung on for dear life, laughing in spite of herself.

Wonderland, it seemed, was exactly as mad as ever, just with worse customer service.

Alice decided later that the most troubling part was not the sheep.

The sheep was troubling, certainly. It stood in the middle of the lane with the quiet confidence of something that knew it had always been there and always would be. Its wool was the colour of old clouds, its eyes were thoughtful, and around its neck hung a small wooden sign that read:

BACK SOON

Alice read it twice.

“I don’t think that’s how sheep work,” she said politely.

The sheep regarded her in silence, chewing in a manner that suggested deep consideration of the matter. Then it turned, quite deliberately, and began to walk away down the lane.

“Excuse me,” Alice called. “I think you’ve dropped your…”

The sheep did not stop.

Alice hesitated. She had been taught very firmly never to follow strange animals, especially those displaying written notices. But the lane itself seemed to lean after the sheep, curving gently, as if it preferred that direction. Even the hedges appeared to listen.

With a sigh that felt far older than she was, Alice followed.

The lane led her into Ballykillduff.

At least, that was what the sign said. It stood crookedly at the edge of the village, its letters faded and patched over, as though someone had changed their mind halfway through spelling it. Beneath the name, in much smaller writing, was a second line:

Population: Yes

Alice frowned.

The village looked entirely ordinary, which in her experience was often a bad sign. Stone cottages huddled together as if exchanging secrets. A postbox leaned sideways in what might have been exhaustion. Somewhere, a clock was ticking very loudly and very wrongly.

The sheep paused beside the postbox.

It did not look back. It did not need to.

The postbox cleared its throat.

“Letter?” it asked.

Alice jumped.

“I—no,” she said. “I mean, not yet.”

“Take your time,” said the postbox kindly. “We’ve plenty of it. Too much, if you ask me. It keeps piling up.”

The sheep nodded.

“I’m sorry,” Alice said carefully, “but could you tell me where I am?”

The postbox considered this. “Well now,” it said, “that depends. Where do you think you ought to be?”

“I don’t know,” Alice admitted.

“Ah,” said the postbox, sounding relieved. “Then you’re exactly right.”

The sheep turned at last and met Alice’s eyes. For a moment she had the strange feeling that it recognised her.

Then the ground beneath her boots gave a polite little sigh and began to sink.

Alice did not scream. She had learned by now that screaming rarely helped.

Instead, as Ballykillduff folded itself carefully over her like a story closing its covers, she wondered whether anyone at home would notice she was gone.

The sheep watched until she vanished completely.

Then it picked up its sign, turned it around, and hung it back around its neck.

BACK AGAIN.

“Faster, Barnaby, faster!” squeaked Alice, clinging desperately to the leathery hide of her unusual steed.

Barnaby, who was, to be perfectly clear, a baby albino hippo wearing a tiny, slightly crooked monocle, did not need encouraging. He was currently tearing across a very normal-looking riverside meadow—which was, of course, absolutely unacceptable for a meadow adjacent to Wonderland—with the speed and grace of a terrified washing machine. His little legs pumped like pink pistons, and his substantial body bounced alarmingly, causing Alice’s blonde hair ribbon to stream out behind her like a distressed banner.

“We must retrieve the Duchess’s runaway teacup!” she yelled, her voice vibrating from the sheer velocity. “It’s got all her important thoughts in it! Specifically, the one about why flamingos are structurally unsound as croquet mallets!”

Barnaby snorted, a sound that was half sneeze and half submerged tuba, causing his monocle to slip precariously over his eye. He did not slow down, mostly because he believed the patch of particularly lush clover just ahead held the secret to solving his life’s great mystery: “Do my toes have a collective name?”

The absurdity had begun precisely three minutes earlier when Alice, having narrowly avoided a philosophical debate with a disgruntled caterpillar about the proper use of semicolons, stumbled upon Barnaby trying to organize a pile of damp pebbles by their emotional state.

“Excuse me,” Alice had said politely, “but are you running away from something?”

Barnaby had looked up, adjusted his monocle, and declared, “On the contrary, Miss. I’m running towards the inevitable conclusion that I am an under-appreciated dramatic prop in this entire affair! Also, a teacup just rolled past me. It was humming something by the Mad Hatter, which is simply poor form for porcelain.”

And so, the chase was on.

They thundered past a family of hedgehogs attempting to build a miniature, functional guillotine out of biscuits. They leaped over a giant chessboard where the Queen of Hearts was having a surprisingly mild-mannered argument with a pawn about dental hygiene.

“It’s catching up!” cried Alice, glancing over her shoulder.

“Nonsense!” shouted a small, reedy voice from inside her pocket. It was the Duchess’s teacup, which had, apparently, decided to reverse course and hitch a ride on Barnaby’s tail before Alice noticed. “I’ve been here the whole time! I just wanted to see if the view was better from the back of a moderately athletic ungulate! Now, if you please, I need to get back to the Duchess before she tries to substitute the March Hare for a serving dish!”

Barnaby, hearing the word “ungulate,” skidded to a halt in a cloud of dust and slightly bruised daisies. He turned his wide, innocent, pink face back to Alice.

“Did I just hear someone refer to me as an ungulate?” he asked, deeply offended. “I’ll have you know, I am a pachyderm! A magnificent, mud-loving pachyderm! And now that the philosophical dilemma has been resolved, I shall revert to my natural pace of ‘ponderously waddling to the nearest body of water to look thoughtful.'”

Alice sighed, slid off the hippo’s back, and neatly caught the monocle before it hit the ground. She tucked the teacup safely under her arm.

“Well, Barnaby,” she said, giving his moist snout a pat. “That was entirely too much excitement for a Thursday. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I believe I need to find a nice, quiet rabbit hole where nothing makes sense but everything is at least stationary.”

Barnaby simply smiled, the picture of serene, monocled pachyderm wisdom. He then slowly, carefully, and with great dignity, rolled into the river and sank immediately out of sight, leaving only a single, enthusiastic bubble.