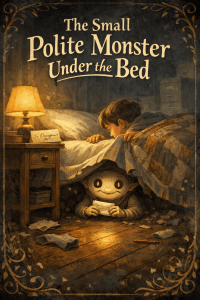

No one noticed the monster at first, because it was very careful not to be noticed.

This was partly manners, and partly survival.

It lived beneath the bed in the narrow, dust-soft space where lost socks go to forget themselves. It was not large. About the size of a loaf of bread, if bread had eyes and a posture suggesting apology. Its skin was the colour of old paper. Its teeth were small, tidy, and almost never used.

Most importantly, it had been raised correctly.

The monster waited until the child was asleep before emerging, and even then it did so quietly, easing one claw onto the carpet and pausing to listen, just in case.

If the child stirred, the monster froze.

If the child sighed, the monster nodded, sympathetically.

If the child kicked the blankets off, the monster tucked them back in.

On its first night, the monster wrote a note…

Do you want to read more?

Click HERE and be scared!

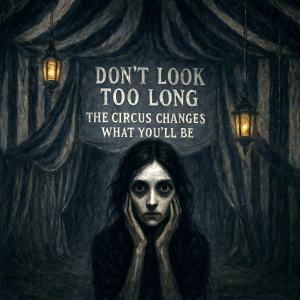

When twilight settles over Ballykillduff, a strange hush falls across the fields… and a tent no one saw being built begins to glow.

“The Circus Came at Twilight” is a dark, melodic folk ballad inspired by the haunting tale of The Circus of the Grotesques — a place where shadows breathe, lanterns flicker without flame, and laughter sometimes sounds like weeping.

This version blends cinematic musical-theatre emotion with eerie dark-folk storytelling, creating a mysterious, immersive journey into the heart of a cursed circus that appears only at dusk… and remembers everyone who enters.

✨ About the Song

🎵 Style: Dark folk • Cinematic • Theatrical

🎤 Vocals: Haunting male lead

🎻 Mood: Melancholy, magical, foreboding

🎪 Inspired by the story Circus of the Grotesques

✨ What You’ll Hear

• Warm yet eerie harmonies

• Whispering strings and distant calliope echoes

• A rising sense of mystery as the tent “comes alive”

• Lyrics that weave a ghostly narrative of arrival, memory, and fate

✨ Story Theme

The circus arrives without warning.

It grows like moonlight on empty ground.

Those who step inside may leave… but not unchanged.

Read the entire twelve chapter story HERE

(Spoken, low and hypnotic)**

“Ladies… gentlemen… wanderers in the dusk…

Lean closer now.

Don’t worry—

the shadows lean closer too.

In this tent of trembling light,

names slip,

faces shift,

and truths grow thin as moth-wings.

Repeat after me—

silently,

inside your obedient little minds:

Look not too long…

Look not too deep…

The circus wakes what should not wake from sleep…

For here, under the pearl and black,

the mirrors do not show you—

they show

what you fear you are becoming.

Listen…

Do you hear the canvas breathing?

Do you feel the ground remembering your steps?

Good.

It means the circus has seen you.

Now hush.

The show begins when the tent blinks.

And if it keeps its eyes open…

you may yet walk out

the same shape

as you walked in.”

The air in the Wasteland of the Forgotten didn’t move; it pressed, thick with the dust of ages and the silence of the long-dead. This was the domain of Malak, the Watcher.

Malak was less a creature and more a convergence of dread, draped in rags the color of grave-soil. His face was a hollowed skull, his eyes two pinpricks of yellow hunger. In his skeletal hand, he held a lantern—an antique cage of pitted brass, whose light was an impossible, warm amber. It was the only light in the infinite black, and it was the problem.

His sole, unending task was to patrol the endless, cracked earth. The cracks weren’t from drought; they were fissures in reality. Beneath the crumbling crust lay the Before, and the things that still squirmed there longed for the air, for a taste of the thin, weary world Malak occupied.

The weirdness wasn’t the monster, but the light. Malak wasn’t lighting his own way; he was illuminating the cracks. And every time the warm glow fell upon a particularly deep, vibrating fissure, he had to stop. He’d bring the lantern close, its heat making the dust shimmer, and listen.

Tap. Tap-tap.

The sound was like a tiny, insistent knuckle-rapping on glass. It was the sound of something from the Before—something with too many limbs and no real shape—testing the barrier. Malak’s duty was horrifyingly simple: if the tapping was too quick, too loud, or if the amber light caught a sudden, glistening wetness oozing up, he had to feed the crack.

Slowly, agonizingly, he would lower his lamp, not snuffing it, but placing it gently over the most active fissure. The tap-tapping would cease, replaced by a sucking sound, and the light—the precious, warm, only light—would dim, then flicker, then be gone. The thing below had consumed the illumination, the hope, of the little flame.

Then, Malak would remain in the absolute dark, his skull tilted, waiting. After an eternity that might have been a minute, a tiny, fresh flicker would reignite inside the empty brass cage. A new spark, a new life, drawn from the sheer, unending need for a Watcher. And Malak would lift the lamp, its amber glow illuminating the next set of cracks, and continue his patrol, knowing that eventually, he would have to feed the light away again.

He was the guardian of the dark, and the perpetual sacrifice of the light.

The figure known only as the Scribe of Silence (the lantern-bearer) had a singular, maddening realization: the cracks in the ground were not new. They were the seams of an ancient wound, and the things that crawled out of them had a disturbing habit.

The ruined tombstones scattered across the cracked plain were the first victims. They weren’t merely weathered by time; they had been scoured. Malak, the Scribe, knew the process well, for it was his fault.

A thousand years ago, this was a proud, vast necropolis, a fortress of memory. When the Great Tear first opened, spewing forth the Grave-Flesh—amorphous, hungry, and impossibly patient—the people fled. The priests tried to seal the Tear with prayer. The warriors tried with steel. Malak, then a common grave-tender, watched them all fail.

The Grave-Flesh did not eat bodies. It ate identity.

When it spilled out, it crept onto the grandest mausoleums, the tallest pillars, and the most lovingly carved headstones. It covered the stone like a damp, black mold. Where it lingered, the names disappeared. The dates vanished. The sentimental epitaphs—Beloved Father, True Friend, Eternal Rest—were polished away until the stone was blank and cold.

The crumbled tombstones in the image are the ones the Grave-Flesh has finished feeding on. They are smooth, faceless wreckage, the stone equivalent of a man’s mind wiped clean.

Malak’s curse is that he was the last one alive, forced to watch the final, agonizing erasure of his own people. His lantern’s light is not a guide, but a warning beacon he must shine only on the new cracks. He is searching for any stone that still carries an inscription, an old mark, or a piece of a forgotten name.

His fear is that one day, he will turn his lantern’s gaze upon the shattered remnants of the necropolis and find that not a single stone bears a mark, leaving the Wasteland perfectly, horribly, clean—the final triumph of the Grave-Flesh. And when the memories are all gone, Malak knows, he will be next.

A Tale of County Carlow

It was in the late summer of the year 1848 that I made my visit to the town of Tullow in the county of Carlow. My business there, though of a trifling and unromantic nature, afforded me the opportunity of passing several days amidst scenery that, if not grand in the manner of the Wicklow mountains, yet possessed a certain sober charm which spoke to the imagination in a more secret, and therefore more lasting, fashion.

The Barrow river meandered with an easy grace; the hedgerows were thick with bramble and honeysuckle; and in the quiet of the evening one might hear the calling of corncrakes from the meadows. I took lodgings in a modest inn not far from the market square, and soon discovered that my host was a man of much conversation and a relish for recounting tales of the district. It was he who first directed my attention to Haroldstown Dolmen, that curious relic of forgotten antiquity, standing solitary in a field between Tullow and Carlow town.

“You’ll see it if you take the back road,” said he, pouring me a glass of the local cider. “A great flat stone balanced upon others, like a table set for giants. Some say it’s but the burial place of kings long turned to dust.” Here he leaned closer, lowering his voice with a relish, “others say it is a doorway. And once in a while, sir, the dead themselves will come out to sit upon it.”

I laughed lightly, as travellers often do when hearing the superstitions of a countryside not their own. Yet I made a note to visit this monument, for I confess I am not insensible to the charm of old stones and the whisperings they provoke.

Two evenings later, when the weather was clear and the sky washed with a mellow gold, I set out upon the road he had indicated. The hedges on either side were high, and the hum of bees was still in the air, though the day had begun to cool. I walked for some time before the road turned, and then suddenly it came into view.

There, in the middle of a wide, low field, stood the dolmen. A capstone of enormous weight lay supported upon uprights, casting a shadow long and black upon the grass. The field was otherwise empty, save for a scatter of nettles near the gate and the distant silhouettes of sheep against the horizon. It was a place of uncommon stillness, and I confess I paused at the gate, uncertain whether to proceed.

It was then I heard it—the faintest thread of music. At first I thought it the sound of some shepherd’s pipe carried on the wind. But no: it was not a rustic air, nor yet a jig or reel. It was a note of a harp, clear and pure, rising and falling with a solemnity that chilled me. And following that a voice!

The voice was of a woman, and such a voice I had never heard before nor since. It sang not in words that I could discern, but in tones that seemed to touch the very marrow of my bones. Sweet, mournful, tender yet with a power that shook the air like the tolling of a bell. I was drawn forward, step by step, until I stood at the edge of the field.

Upon the dolmen lay a woman, as though in careless repose. Her hair was of a deep red, falling about her shoulders like a mantle of fire. She wore a gown of green velvet that glimmered in the low light. Her arms were raised slightly, her pale hands outstretched as if to shape the air through which her song flowed.

Beside her, in the grass, was a man. He sat upon an ordinary chair, such as one might find in a parlour, though how it had come there I cannot imagine. His face was thin, his complexion ghastly pale, and his eyes fixed with an unnatural solemnity upon the strings of the harp which his hands commanded. His aspect was of one who performed not for pleasure, but by some inexorable compulsion.

The sight held me immobile. The woman’s gaze, though her eyes were half-closed in her song, seemed nevertheless to rest upon me. The harpist did not look up. The music rose, wound itself about me, and I felt my breath catch.

Then the woman ceased her singing, and the harpist let his fingers fall silent. The hush that followed was more terrible than the sound itself. Slowly, the woman turned her head. Her eyes, green as glass, clear as water, met mine.

“You hear us,” she said. Her voice was low, but carried across the distance without effort. “Most do not.”

I could not reply.

She rose then from the dolmen, her long gown trailing like mist. Yet I swear, and would swear upon any book, that the moss upon which she had lain bore no impress of her form, no trace of disturbance.

The harpist lifted his face. His expression was grave, and I observed with a start that the chair upon which he sat was sunken deep into the soil, though the ground about it was hard and dry. He struck a single string, one sharp, brittle note, and in that instant the dolmen itself seemed to shudder.

The woman advanced a step, her eyes never leaving mine. “Come closer,” she whispered. “Every ear that hears our song is chosen. We need one more voice.”

At this, some dreadful instinct awoke within me. My whole being revolted at her invitation, yet my limbs moved of their own accord, one step into the field, then another. The grass seemed higher than before, the nettles hemming me in, though I had not marked them so thickly when I entered.

I do not know how long I stood thus, poised between compulsion and terror. But suddenly a cloud passed across the setting sun, and a shadow fell. In that dimness I found strength, turned, and stumbled back through the gate to the road.

Behind me, as I fled, the music began again. This time it was sweeter, more coaxing, filled with sorrow, as though the very air grieved at my departure. Yet I did not look back. I ran until the roofs of Tullow were in sight, and the sound was lost in the ordinary bustle of the town.

When at last I returned to my lodging, I found my host waiting. He looked at me keenly and said, “So, you have been to Haroldstown.”

I could not answer him. I had no wish to speak of what I had seen, nor indeed could I have put it into plain words without doubting my own senses.

But in the nights that followed, as I lay awake in my chamber, I thought I heard, faint and far, the trembling of a harp string, and a woman’s voice calling in tones of sweetness and despair.

It is now many years since that evening. I have never returned to Haroldstown, nor do I intend to. Yet sometimes, when summer fades and the wind carries the scent of nettles and cut grass, I hear again the echo of that song. And then I wonder what would have become of me had I taken one step more, and placed my hand upon the dolmen’s cold stone.

(From the Papers of Canon O’Shaughnessy, with Notes and an Appendix on “An Faire Dorcha”)

By Dr. H. C. Ellingham, F.S.I.A.

In arranging the literary remains of the late Canon O’Shaughnessy of Carlow, I discovered a packet of letters, tied with twine and labelled in his hand “Ballyroguearty — Donnelly.” These were addressed to him from Father Donnelly, parish priest of Ballyroguearty, in the closing months of 1874.

The contents pertain to certain manifestations within the parish church of St. Brendan’s. I beg leave to lay the documents before the Society, together with marginalia of Canon O’Shaughnessy, and such commentary as I may append.

Letter, Oct. 18th, 1874:

“I perceived at the last pew, beneath the north wall, a figure robed in darkness, so dense the candles gave it no light. Its head was bowed, and it muttered in broken Latin.”

Transcription (as copied by Donnelly):

MIS-ER-E-RE NOBIS

DEVS TENEBRARVM

ORDO ÆTERNVM

EXTERMINARE PECCATVM

(Translation: “Have mercy upon us, God of Shadows, eternal order, destroy sin.”)

Letter, Nov. 2nd, 1874:

“Wax poured like wounds from the candles; the bells swung without hand; the saints wept black tears. Through it all the shadow chanted…”

Transcription:

SANC-TV[S] SANC-TV[S] SANC-TV[S]

ORDO DOMINATORVM

PLENVM EST VNIVERSVM

GLORIA TENEBRARVM

(A parody of the Sanctus. Here the glory belongs to shadows, not the Lord of Hosts.)

Want to reead more?

Click on the link, below, and be scared!

The Shadow that learned to pray

I saw a lone figure, a shadowy sight,

While walking the woods one dark wintry night,

So I quickened my pace and hurried my step,

To escape its attention and forget we had met.

The mysterious figure following my route,

Shadowing my steps, copying my truth,

Never let up despite my great pains,

To escape its attention and break free of its reign.

Minutes passed, hours and then days,

Weeks followed by months and years deathly grey,

Until one dark wintry night while walking the same wood,

I confronted the thing that held onto my truth.

Having prevailed over fear, I could see what it was,

An angel, a guardian angel, sent down from above,

Then it opened its wings, showing me the light of my life,

And I welcomed it into my soul with delight.