Click HERE to read this exciting new story – for free.

One followed a rabbit down into the dark,

The other a cyclone that left its own mark.

On a road paved in gold, where the green towers rise,

They met for a moment and shared their surprise.

Both wearing ribbons and dresses of blue,

In worlds where the logic is never quite true.

One spoke of riddles and tea with a cat,

The other of wizards and where home was at.

“The cards are all shouting!” the blonde one declared,

While the girl with the braids found herself rather scared.

“There’s a lion who cries and a man made of tin,

And a city of emeralds we’re meant to go in.”

They paused by the signpost that points the same way,

In the soft, hazy light of a magical day.

With a sip of her tea and a click of red heels,

They pondered how living a fairy tale feels.

No logic or compass could show them the door,

Between Kansas, and London, and Never-Before.

But for one quiet second, the wanderers stood—

Two girls lost in dreams, as all wanderers should.

Alice Meets Dorothy

The sun, a pale, milky orb in the sky, cast long, shifting shadows along the path of gold bricks. Dorothy, her blue gingham dress a familiar comfort, stood with a curious expression. Before her, a girl with hair the color of sunlight and a similar blue dress held a steaming teacup, a delicate saucer resting precariously on the rough, uneven bricks.

“Emerald City?” the blonde girl mused, peering at the signpost that read the same words twice. “How perfectly uninteresting. All cities are rather green, if you ask me, with all the grass and trees.”

Dorothy blinked. “But it’s Emerald City! Everything is green inside. The people wear green spectacles, and the palace is green, and—”

“Oh, like a rather large, sparkly bottle then?” the other girl interrupted, taking a sip of her tea. “I once met a bottle that contained a rather rude pigeon. Do you have many rude pigeons here?”

“Pigeons?” Dorothy frowned, trying to recall. “Well, I haven’t really noticed. I’ve been so busy trying to get to the Wizard.”

“A wizard, you say?” The blonde girl’s eyes widened slightly. “How dreadfully dull. Are they anything like a Dodo? Or a March Hare, perhaps? They are quite good at making things disappear, though often they just hide them.” She gestured with her teacup towards the path. “Are you going to a tea party?”

Dorothy shook her head, a little bewildered. “No, I’m going to ask the Wizard to send me home to Kansas. And my dog, Toto, needs to go home too.” She looked around. “Where’s your dog?”

“A dog? Oh, I don’t have a dog,” the girl replied, looking down at her cup. “I have a rather persistent White Rabbit. He’s always late for something or other. And a Ches—” She stopped, a peculiar glint in her eye. “No, I mustn’t mention him. It makes his smile appear, and then he’s terribly difficult to remove from conversations.”

Dorothy tilted her head. “A rabbit that’s always late? And a disappearing smile?” This world felt even stranger than Oz. “Are you… lost too?”

The blonde girl finally looked directly at Dorothy, a flicker of something familiar in her gaze. “Lost? One is never truly lost when one has a destination, however illogical. Though I confess, ‘Emerald City’ wasn’t on my itinerary. I was rather hoping for a game of croquet.” She gestured to the fallen teacup beside her feet. “Though this tea has gone quite cold, I daresay. Would you care for a cup?”

Dorothy looked from the cold teacup on the ground to the girl’s outstretched hand, holding another. The Emerald City gleamed in the distance. “I suppose… a small cup couldn’t hurt.” She had, after all, met a talking lion and a scarecrow. What was one more peculiar encounter on the road?

The meeting of the girls was polite, but the meeting of their companions would be a much more baffling affair!

Toto was a dog of simple, sturdy principles. He liked bones, he liked chasing the occasional crow, and he liked things to stay where he could see them.

He was sniffing a patch of particularly bright poppies when a tail appeared. Just a tail. It was striped, purple, and twitching lazily in the air about four feet off the ground. Toto gave a sharp, inquisitive bark.

“Oh, do stop that,” a voice purred from the empty air. “It’s dreadfully loud, and I’m trying to contemplate the nature of a ‘Kansas’.”

A pair of wide, yellow eyes flickered into existence above the tail, followed by a grin so wide it seemed to be holding the rest of the face together. Toto’s ears flattened. He was used to monkeys with wings and lions who cried, but a cat that was only half-finished was an insult to his canine senses.

Toto growled, a low vibration in his chest.

“A growl?” the Cheshire Cat remarked, its ears finally materializing. “How singular. In my forest, we growl when we’re pleased and wag our tails when we’re angry. Or is it the other way around? It hardly matters, since I haven’t got a tail at the moment.”

The Cat vanished entirely, leaving only the floating grin. Toto lunged, snapping at the empty air where the nose should have been, but his teeth met only the scent of tea and ozone.

“You’re quite a determined little thing,” the grin said, reappearing behind Toto’s left ear. “But you’ll find that biting the air is a very hungry business. Tell me, does your girl always walk on such a yellow road? It’s a bit loud for the eyes, don’t you think?”

Toto turned in a circle, barking at the floating teeth. He didn’t care about the color of the road; he just wanted this cat to pick a shape and stick to it.

“He’s not a dog, Toto,” Dorothy called out from a distance, sensing the commotion.

“And he’s certainly not a rabbit,” Alice added, peering over.

The Cheshire Cat began to fade again, starting with the tip of its tail. “We’re all mad here, little dog. Some of us just have the decency to hide the evidence.”

With one final, mocking wink of a yellow eye, the cat was gone. Toto sniffed the spot, let out one final, huffy “woof,” and trotted back to Dorothy’s side. He decided then and there that he much preferred the Wicked Witch; at least she stayed solid when you bit her.

Alice in the Magical Square of Tartaria

Ballykillduff is a village that thinks quietly.

Lanes hesitate. Grass leans when it should not. Things happen just slightly to the side of where they are supposed to be. Alice has lived there long enough to know this, and just long enough not to question it.

So when a crease appears in the air behind the Old Creamery, and a place called Tartaria slips sideways into existence, Alice is the only one who notices — and the only one who understands that some places survive by being remembered badly.

Tartaria is a civilisation that vanished by behaving too well. Now it endures in a state of almost compound memory: misremembered, misfiled, and dangerously unfinished. Maps argue. Councils disagree. Scholars from Outside begin asking sensible questions — the most dangerous kind of all.

As Alice moves between Ballykillduff and Tartaria, she discovers that memory is not passive, certainty is a trap, and being understood may be far worse than being forgotten. Worse still, Tartaria begins to misremember her.

To save both worlds, Alice must learn how to remember wrongly on purpose — without doing it too well.

Alice in Ballykillduff and the Almost-Remembered Tartaria is a whimsical, quietly unsettling fantasy in the tradition of Lewis Carroll: a story about places that think, truths that refuse to settle, and the peculiar courage it takes to remain unfinished.

To read this new story click on the link below.

There was a man who was always almost there.

This was not a rumour, nor a manner of speech, but a well-established fact, agreed upon by the town, the postman, and the chairs that were kept ready for him. He was, at all times, five minutes away.

“Five minutes?” people would ask.

“Always five,” replied everyone else, with the weary confidence of those who have checked.

If he was said to be crossing the bridge, he was five minutes from the bridge. If he was climbing the hill, he was five minutes from the top. If he was known to be standing just outside the door, hand raised to knock, then surely — unmistakably — he was five minutes from doing so.

No one had ever seen him arrive.

This did not stop them knowing him well.

They spoke of him often and with fondness. He preferred his tea strong but forgot to drink it. He laughed quietly, as though worried it might disturb something. He had a habit of saying “ah” before responding, which suggested thoughtfulness even when none followed. Children were warned not to take his seat, which remained empty at the end of the long table, with a cup that grew steadily colder by the hour.

“He’ll be here in a moment,” someone would say.

And it was true.

Just not yet.

The letters arrived before he did.

They came addressed in a careful hand, always with the correct name, always with no return address. Some were invitations. Some were apologies. One was a birthday card that arrived exactly on time and sang loudly when opened.

The town clerk attempted to file them, but could not decide where.

“He hasn’t come yet,” she said, holding a small stack of envelopes.

“No,” said the baker, “but they’re definitely his.”

And so they were placed neatly on the hall table, where they waited patiently, much like their owner.

Only one person found this unsettling.

Her name was Ada, and she had recently arrived, which made her suspicious of things that had been accepted for too long. Ada noticed the chair first. Then the tea. Then the way conversations bent slightly around a person who was not there.

“When will he arrive?” she asked.

“In five minutes,” said the room.

“But when did you first say that?”

There was a pause.

“Well,” said someone carefully, “quite some time ago.”

Ada decided to meet him.

Not properly, of course — that seemed unlikely — but she resolved to walk out and find where he was stuck being almost. She followed the road everyone said he was on, past the hedges that leaned in to listen, past the gate that never quite closed.

After some time, she saw him.

Or nearly did.

There was a figure in the distance, exactly the right shape, exactly the right amount of familiar. He was close enough to recognise, but far enough to remain uncertain, as though the world itself had misjudged the focus.

She waved.

The figure raised a hand.

She stepped forward.

He stepped forward too.

The distance remained.

It was then that Ada did something unusual.

She stopped walking forward.

Instead, she took a careful step backward.

The world hesitated.

The air felt as though it had mislaid a rule. Birds paused mid-thought. The hedges rustled, offended. The distance between them wavered, thinned, and for the first time appeared unsure of itself.

She took another step back.

The man was suddenly closer.

Not by much — but enough.

She smiled.

“So that’s it,” she said. “You’re not late. You’re being approached incorrectly.”

The man laughed, quietly, exactly as described.

They did not walk together.

That would have spoiled things.

Instead, Ada continued stepping backward, slowly, respectfully, while he moved forward, relieved but cautious, as though arrival were a delicate business that must not be rushed.

When they reached the edge of town, the chair was still empty.

The tea was still cold.

But the five minutes were gone.

No one noticed at first.

Later, someone would remark that the waiting felt different — lighter, somehow — as though something expected had finally been allowed to happen.

As for the man, he did eventually arrive.

Not loudly.

Not all at once.

Just enough to sit down, take a sip of tea, and say “ah,” as if he had been there all along.

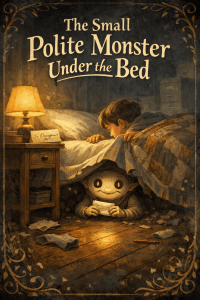

No one noticed the monster at first, because it was very careful not to be noticed.

This was partly manners, and partly survival.

It lived beneath the bed in the narrow, dust-soft space where lost socks go to forget themselves. It was not large. About the size of a loaf of bread, if bread had eyes and a posture suggesting apology. Its skin was the colour of old paper. Its teeth were small, tidy, and almost never used.

Most importantly, it had been raised correctly.

The monster waited until the child was asleep before emerging, and even then it did so quietly, easing one claw onto the carpet and pausing to listen, just in case.

If the child stirred, the monster froze.

If the child sighed, the monster nodded, sympathetically.

If the child kicked the blankets off, the monster tucked them back in.

On its first night, the monster wrote a note…

Do you want to read more?

Click HERE and be scared!

The Man with a Hippo on His Head

There once was a man (quite respectable, too)

Who awoke with a problem he hadn’t a clue:

A baby hippo,

Quite small for a hippo,

Was sitting up top like a hat made of goo.

It snorted politely and yawned with a plop,

Then wiggled its toes and refused to get off.

“I’m late for my tea!”

Cried the man, urgently,

But the hippo just drooled and went plopity-plop.

He tried hats and ladders and standing quite still,

He tried reasoning gently and shouting with will.

But the hippo said “No,”

In a voice very slow,

And munched on his hair like a casual meal.

They walked through the town with a wobble and sway,

Past people who stared in a terribly polite way.

“Is it fashion?” they said,

Pointing up at his head,

Or “Perhaps it’s a Tuesday,” then shuffled away.

At last, tired of balance and hippoish weight,

The man sighed, “I suppose this is simply my fate.”

So he bought two new shoes,

One umbrella for snooze,

And a biscuit for hippos (they’re partial to eight).

Now they’re quite the pair, as odd pairs often are:

A man with ambition, a hippo who snores.

And if you should meet them,

Do try not to greet them—

Just nod, and move on, and ask nothing more.

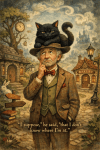

There once was a man with a hat who believed, quite firmly, that he knew exactly where he was at.

He stood in the middle of a street that looked familiar enough, nodded wisely to himself, and announced, “Ah yes. Here.”

Unfortunately, his hat was a cat.

This was not immediately obvious, as the cat had mastered the ancient and difficult art of Looking Like a Hat. It sat very still upon the man’s head, curling its tail neatly around the brim and narrowing its eyes in a way that suggested felt, wool, or possibly tweed.

“Left,” said the man confidently, and turned left.

“No,” said the hat.

The man paused. “Hats don’t usually talk,” he said.

“I’m not usually a hat,” replied the cat, adjusting itself slightly and knocking the man’s sense of direction sideways.

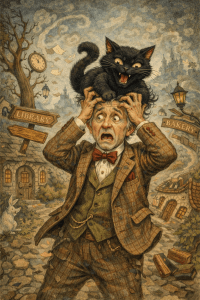

They walked on. Or rather, the man walked on, while the hat gently leaned him in directions that felt interesting at the time. Streets rearranged themselves. Doorways swapped places. A bakery became a library. A lamppost insisted it had always been a tree.

“Are we lost?” asked the man.

“Entirely,” purred the hat. “But very stylishly.”

By now the man noticed that every time he felt certain, the world became uncertain, and every time he admitted he didn’t know where he was, things calmed down a little. The cat-hat hummed contentedly and pointed with one ear toward a place that might have been somewhere or might have been nowhere at all.

At last, the man sighed. “I suppose,” he said, “that I don’t know where I’m at.”

The hat purred, pleased at last to be properly acknowledged, and for the first time all day, they arrived exactly where they were meant to be.

Which, of course, was nowhere in particular. And that was perfectly fine.

There once was a man with a hat who believed, with the stubborn confidence of the mildly informed, that he knew exactly where he was at.

He stood quite still, for standing still always felt like proof. The street beneath him did not object, though it had rearranged itself several times since he arrived. The houses leaned. The sky blinked. A signpost nearby whispered directions to itself and then forgot them.

The man nodded. “Here,” he said aloud.

At this point, the hat cleared its throat.

The man did not look up, for hats were not supposed to have throats, and it is rude to notice such things when they do. The hat, however, was a cat, and cats have very definite opinions about being ignored.

“You are mistaken,” said the hat softly, close to the man’s thoughts rather than his ears.

“I can’t be,” said the man. “I know where I’m at.”

The hat tightened slightly.

With this small adjustment, the street lengthened, the corners bent inward, and the idea of where slid a few inches to the left. A bakery across the way shuddered and decided it had always been a courtroom. A lamppost turned its head.

The man felt a peculiar wobble behind his eyes.

“Left,” he said, pointing.

“No,” said the hat.

The man frowned. “Hats shouldn’t argue.”

“I’m not arguing,” said the hat. “I’m correcting.”

They began to walk, though the man could not recall starting. Each step took him somewhere slightly less certain than the one before. When he felt sure, the ground softened. When he hesitated, it tilted. The cat-hat purred, pleased with the arrangement.

“Are we lost?” the man asked at last, his voice thinner than before.

The hat paused. “Lost implies a map,” it said. “You gave that up three streets ago.”

The man reached up, intending to remove his hat, but found that his hands could not agree on where his head was. His thoughts had begun to wander without him.

“I don’t know where I’m at,” he said quietly.

The world stopped moving.

The hat loosened its grip, satisfied. “That,” it said, “is much better.”

And with that admission, the man arrived—precisely, irrevocably—exactly where he was.

Which was nowhere he could leave, and nowhere he could name.

The hat settled back into place and went to sleep, dreaming of maps that bite.

Alice stopped because the sign had stopped first.

“TARTARIA,” it said, as though announcing a sneeze that never quite arrived. The cottage behind it pretended to be a cottage, the path pretended to be going somewhere, and the air smelled faintly of yesterday.

Alice adjusted her basket, which was full of eggs that were thinking about becoming clocks, and stepped forward carefully—because places that are formerly elsewhere have a habit of remembering you before you remember them.