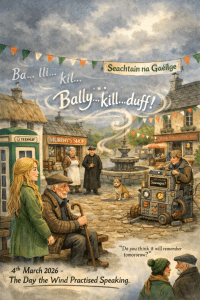

Seven for a Secret, Never to Be Told

Everyone in Ballykillduff knew the rhyme. They learned it young, usually from someone older who lowered their voice for the last line.

One for sorrow.

Two for joy.

Three for a girl.

Four for a boy.

Five for silver.

Six for gold.

Seven for a secret, never to be told.

Most people laughed at it. Some people touched wood. Nobody ever talked about seven.

Alice saw them on a Tuesday morning, standing along the hedge at Curran’s Lane.

Seven magpies. Neat as fence posts. Silent as if silence were a rule they were following carefully.

Alice stopped walking.

The hedge itself felt wrong. Not dangerous. Just… held together too tightly, like someone smiling for longer than was comfortable.

She counted them twice. She always did when things felt important.

One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven.

All seven turned their heads together and looked at her.

“Right,” Alice said quietly. “It’s that sort of day.”

People passed along the lane without noticing anything at all. Mr Keane walked by whistling. Mrs Donnelly hurried past with her shopping. No one looked at the hedge. No one slowed down.

Only Alice stood there.

The magpies did not speak. They had never needed to.

Long ago, Ballykillduff had made a decision.

It was not a cruel decision. It was a tired one.

Something sad had happened. Something that could not be fixed. A thing with a name, and a place, and a day that people still remembered too clearly. After a while, the village agreed to stop saying it out loud. Not because it wasn’t real, but because remembering it every day was making it impossible to live the next ones.

So the remembering was set aside.

And the magpies stayed.

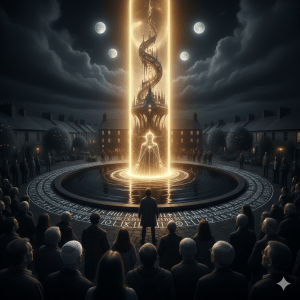

They stayed because someone had to remember, and magpies are very good at keeping what others lay down. Not just shiny things, but moments, and names, and truths that no longer fit anywhere else.

The rhyme was never meant to predict luck.

It was a warning.

Seven magpies meant a place was carrying a memory it no longer wanted to hold.

One of the magpies hopped down from the hedge and pecked at the ground. Not at soil, but at a flat stone half-buried near the roots. A stone no one stepped on, though no one could have said why.

Alice knew what was being asked of her.

She did not need to know the whole story. She did not need names or details. She only needed to do one thing the village had not done in a very long time.

She knelt and placed her hand on the stone.

“I know,” she said, softly.

That was all.

Not what she knew. Just that she knew something had been there. Something had mattered.

The hedge loosened. Just a little. The air moved again.

When Alice stood up, there were only six magpies left.

They were already arguing with one another, hopping and chattering, busy once more with ordinary magpie business. Shiny things. Important nonsense. The everyday work of being alive.

The seventh magpie rose into the air and flew away, light now, its work finished at last.

Alice walked on down the lane.

Behind her, Ballykillduff continued exactly as it always had. But somewhere deep in its bones, a small, quiet weight had finally been set down properly instead of being hidden away.

And the rhyme, for once, was at rest.

The Eighth Magpie

Everyone in Ballykillduff knew the rhyme. They said it quickly, like a spell that worked better if you didn’t linger on it.

One for sorrow.

Two for joy.

Three for a girl.

Four for a boy.

Five for silver.

Six for gold.

Seven for a secret, never to be told.

Alice had already seen seven magpies once before, and she knew what that meant.

So when she walked along Curran’s Lane and saw eight, she stopped dead.

Seven stood along the hedge, silent and still.

The eighth stood on the path itself, blocking the way.

“Well,” Alice said, “that’s new.”

The eighth magpie was smaller than the others and less patient. It tapped one foot, then the other, as if waiting for a late train.

Seven magpies meant the village had forgotten something important. A sad thing. A thing everyone had agreed not to talk about.

That part had already been done.

Ballykillduff had remembered.

But the eighth magpie had arrived because remembering had changed nothing yet.

The bird pecked sharply at the ground.

Alice followed its beak and saw the problem at once.

The old path had collapsed further down the lane. A fence lay broken. The shortcut people once used had never been repaired. Long ago, someone had been hurt there. That was the secret. That was why people stopped using it.

They had remembered the accident.

They had never fixed the path.

“Oh,” said Alice. “You mean that.”

The eighth magpie nodded briskly.

It wasn’t here for memory.

It was here for mending.

Alice went back to the village and told people what she’d seen. Not the whole story. Just enough.

By evening, someone had brought tools. Someone else brought boards. Someone else brought tea.

By the next morning, the path was safe again.

When Alice returned to Curran’s Lane, there were only seven magpies on the hedge.

Then six.

Then none at all.

The eighth magpie was gone first.

It always is.

Because once something is put right, there is no need for it to stay.

And the rhyme, at last, had room for one more line, though nobody ever said it aloud:

Eight for the thing you do about it.